From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A human mother feeding her child

Parental investment, in

evolutionary biology and

evolutionary psychology, is any parental expenditure (e.g. time, energy, resources) that benefits

offspring.

Parental investment may be performed by both males and females

(biparental care), females alone (exclusive maternal care) or males

alone (exclusive

paternal care).

Care can be provided at any stage of the offspring's life, from

pre-natal (e.g. egg guarding and incubation in birds, and placental

nourishment in mammals) to post-natal (e.g. food provisioning and

protection of offspring).

Parental investment theory, a term coined by

Robert Trivers

in 1972, predicts that the sex that invests more in its offspring will

be more selective when choosing a mate, and the less-investing sex will

have intra-sexual competition for access to mates. This theory has been

influential in explaining sex differences in

sexual selection and

mate preferences, throughout the animal kingdom and in humans.

History

In 1859,

Charles Darwin published

On the Origin of Species. This introduced the concept of

natural selection to the world, as well as related theories such as

sexual selection.

For the first time, evolutionary theory was used to explain why females

are "coy" and males are "ardent" and compete with each other for

females' attention. In 1930,

Ronald Fisher wrote

The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, in which he introduced the modern concept of parental investment, introduced the

sexy son hypothesis, and introduced

Fisher's principle. In 1948,

Angus John Bateman

published an influential study of fruit flies in which he concluded

that because female gametes are more costly to produce than male

gametes, the reproductive success of females was limited by the ability

to produce ovum, and the reproductive success of males was limited by

access to females. In 1972,

Trivers

continued this line of thinking with his proposal of parental

investment theory, which describes how parental investment affects

sexual behavior. He concludes that the sex that has higher parental

investment will be more selective when choosing a mate, and the sex with

lower investment will compete intra-sexually for mating opportunities.

In 1974, Trivers extended parental investment theory to explain

parent-offspring conflict, the conflict between investment that is

optimal from the parent's versus the offspring's perspective.

Parental care

Parental investment theory is a branch of

life history theory. The earliest consideration of parental investment is given by

Ronald Fisher in his 1930 book

The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection,

wherein Fisher argued that parental expenditure on both sexes of

offspring should be equal. Clutton-Brock expanded the concept of

parental investment to include costs to any other component of parental

fitness.

Male

dunnocks tend to not discriminate between their own young and those of another male in

polyandrous or

polygynandrous systems. They increase their own

reproductive success

through feeding the offspring in relation to their own access to the

female throughout the mating period, which is generally a good predictor

of

paternity. This indiscriminative parental care by males is also observed in

redlip blennies.

In some insects, male parental investment is given in the form of a nuptial gift. For instance,

ornate moth

females receive a spermatophore containing nutrients, sperm and

defensive toxins from the male during copulation. This gift, which can

account for up to 10% of the male's body mass, constitutes the total

parental investment the male provides.

In some species, such as humans and many birds, the offspring are

altricial

and unable to fend for themselves for an extended period of time after

birth. In these species, males invest more in their offspring than do

the male parents of

precocial species, since reproductive success would otherwise suffer.

A female lizard defending her clutch against an egg-eating snake.

The benefits of parental investment to the offspring are large and

are associated with the effects on condition, growth, survival, and

ultimately on reproductive success of the offspring. For example, in the

cichlid fish

Tropheus moorii, a female has very high parental investment in her young because she

mouthbroods

the young and while mouthbrooding, all nourishment she takes in goes to

feed the young and she effectively starves herself. In doing this, her

young are larger, heavier, and faster than they would have been without

it. These benefits are very advantageous since it lowers their risk of

being eaten by predators and size is usually the determining factor in

conflicts over resources. However, such benefits can come at the cost of parent's ability to

reproduce in the future e.g., through increased risk of injury when

defending offspring against predators, loss of mating opportunities

whilst rearing offspring, and an increase in the time interval until the

next reproduction.

A special case of parental investment is when young do need

nourishment and protection, but the genetic parents do not actually

contribute in the effort to raise their own offspring. For example, in

Bombus terrestris,

oftentimes sterile female workers will not reproduce on their own, but

will raise their mother's brood instead. This is common in social

Hymenoptera due to

haplodiploidy,

whereby males are haploid and females are diploid. This ensures that

sisters are more related to each other than they ever would be to their

own offspring, incentivizing them to help raise their mother's young

over their own.

Overall, parents are selected to maximize the difference between

the benefits and the costs, and parental care will be likely to evolve

when the benefits exceed the costs.

Parent-offspring conflict

Reproduction is costly. Individuals are limited in the degree to

which they can devote time and resources to producing and raising their

young, and such expenditure may also be detrimental to their future

condition, survival, and further reproductive output.

However, such expenditure is typically beneficial to the offspring,

enhancing their condition, survival, and reproductive success. These

differences may lead to

parent-offspring conflict.

Parents are naturally selected to maximize the difference between the

benefits and the costs, and parental care will tend to exist when the

benefits are substantially greater than the costs.

Parents are equally related to all offspring, and so in order to

optimize their fitness and chance of reproducing their genes, they

should distribute their investment equally among current and future

offspring. However, any single offspring is more related to themselves

(they have 100% of their DNA in common with themselves) than they are to

their siblings (siblings usually share 50% of their DNA), it is best

for the offspring's fitness if the parent(s) invest more in them. To

optimize fitness, a parent would want to invest in each offspring

equally, but each offspring would want a larger share of parental

investment. The parent is selected to invest in the offspring up until

the point at which investing in the current offspring is costlier than

investing in future offspring.

In

iteroparous

species, where individuals may go through several reproductive bouts

during their lifetime, a tradeoff may exist between investment in

current offspring and future reproduction. Parents need to balance their

offspring's demands against their own self-maintenance. This potential

negative effect of parental care was explicitly formalized by Trivers in

1972, who originally defined the term

parental investment to mean

any investment by the parent in an individual offspring that increases the offspring's chance of surviving (and hence reproductive success) at the cost of the parent's ability to invest in other offspring.

Penguins are a prime example of species that drastically sacrifices

their own health and well-being in exchange for the survival of their

offspring. This behavior, one that does not necessarily benefit the

individual, but the genetic code from which the individual arises, can

be seen in the King Penguin. Although some animals do exhibit altruistic

behaviors towards individuals that are not of direct relation, many of

these behaviors appear mostly in parent-offspring relationships. While

breeding, males remain in a fasting-period at the breeding site for five

weeks, waiting for the female to return for her own incubation shift.

However, during this time period, males may decide to abandon their egg

if the female is delayed in her return to the breeding grounds.

It shows that these penguins initially show a trade-off of their

own health, in hopes of increasing the survivorship of their egg. But

there comes a point where the male penguin's costs become too high in

comparison to the gain of a successful breeding season. Olof Olsson

investigated the correlation between how many experiences in breeding an

individual has and the duration an individual will wait until

abandoning his egg. He proposed that the more experienced the

individual, the better that individual will be at replenishing his

exhausted body reserves, allowing him to remain at the egg for a longer

period of time.

The males' sacrifice of their body weight and possible

survivorship, in order to increase their offspring's chance of survival

is a trade-off between current reproductive success and the parents'

future survival.

This trade-off makes sense with other examples of kin-based altruism

and is a clear example of the use of altruism in an attempt to increase

overall fitness of an individual's genetic material at the expense of

the individual's future survival.

Maternal-offspring conflict in investment

The

maternal-offspring conflict has also been studied in animals species

and humans. One such case has been documented in the mid-1970s by

ethologist

Wulf Schiefenhövel.

Eipo women of West New Guinea engage in a cultural practice in which

they give birth just outside the village. Following the birth of their

child, each woman weighed whether or not she should keep the child or

leave the child in the brush nearby, inevitably ending in the death of

the child.

Likelihood of survival and availability of resources within the village

were factors that played into this decision of whether or not to keep

the baby. During one illustrated birth, the mother felt the child was

too ill and would not survive, so she wrapped the child up, preparing to

leave the child in the brush; however, upon seeing the child moving,

the mother unwrapped the child and brought it into the village,

demonstrating a shift of life and death.

This conflict between the mother and the child resulted in detachment

behaviors in Brazil, seen in Scheper-Hughes work as "many Alto babies

remain[ed] not only unchristened but unnamed until they begin to walk or

talk", or if a medical crisis arose and the baby needed an emergency

baptism.

This conflict between survival, both emotional and physical, prompted a

shift in cultural practices, thus resulting in new forms of investment

from the mother towards the child.

Alloparental care

Alloparental care

also referred to as 'Allomothering,' is when a member of a community,

apart from the biological parents of the infant, partake in offspring

care provision.

A range of behaviors fall under the term alloparental care, some of

which are: carrying, feeding, watching over, protecting, and grooming.

Through alloparental care stress on parents, especially the mother, can

be reduced, therefore reducing the negative effects of the

parent-offspring conflict on the mother.

In While the apparent altruistic nature of the behavior may seem at

odds with Darwin's theory of natural selection, as taking care of

offspring which are not one's own would not increase one's direct

fitness, while taking time, energy and resources away from raising one's

own offspring, the behavior can be explained evolutionarily as

increasing indirect fitness, as the offspring is likely to be

non-descendent kin, therefore carrying some of the genetics of the

alloparent.

Offspring and situation direction

Parental

investment behavior enhances the chances of survival of offspring, and

it does not require underlying mechanisms to be compatible with empathy

applicable to adults, or situations involving unrelated offspring, and

it does not require the offspring to reciprocate the altruistic behavior

in any way. Parentally investing individuals are not more vulnerable to being exploited by other adults.

Trivers' parental investment theory

Parental investment as defined by Trivers in 1972 is the investment in offspring by the parent that increases the offspring's chances of surviving and hence

reproductive success

at the expense of the parent's ability to invest in other offspring. A

large parental investment largely decreases the parents' chances of

investing in other offspring. Parental investment can be split into two

main categories: mating investment and rearing investment.

Mating investment consist of the sexual act and the sex cells invested.

The rearing investment is the time and energy expended to raise the

offspring after conception.

Women's parental investment in both mating and rearing efforts greatly

surpasses that of the male. In terms of sex cells (egg and sperms

cells), the female's investment is a lot larger, while males produce

thousands of

sperm cells which are supplied at a rate of twelve million per hour.

Women have a fixed supply of around 400

ova. Also, the acts of

fertilization and

gestation

occur in the women, which compared to the male's investment of just one

cell outweighs it. Furthermore, each intercourse could result in a

nine-month commitment such as gestation (the act of

breastfeeding)

for the woman. From Trivers' theory of parental investment several

implications follow. The first is that women are often but not always

the more investing sex. The fact that they are the more investing sex

has meant that evolution has favored females who are more selective of

their mates to ensure that intercourse would not result in unnecessary

costs. The third implication is that because women invest more and are

essential for the reproductive success of their offspring they are a

valuable resource for men; as a result, males often compete for sexual

access to them.

Males as the more investing sex

For

many species the only type of male investment received is that of sex

cells. In those terms, the female investment greatly exceeds that of

male investment as previously mentioned. However, there are other ways

in which males invest in their offspring. For example, the male can

find food as in the example of balloon flies. He may find a safe environment for the female to feed or lay her eggs as exemplified in many birds.

He may also protect the young and provide them with opportunities

to learn as in many young as in wolves. Overall, the main role that

males overtake is that of protection of the female and their young. That

often can decrease the discrepancy of investment caused by the initial

investment of sex cells. There are some species such as the Mormon

cricket, pipefish seahorse and Panamanian poison arrow frog males invest

more. Among the species where the male invests more, the male is also

the pickier sex, placing higher demands on their selected female. For

example, the female that they often choose usually contain 60% more eggs

than rejected females.

This links Parental Investment Theory (PIT) with

sexual selection:

where parental investment is bigger for a male than a female, it's

usually the female who competes for a mate, as shown by Phalaropidae and

polyandrous bird species. In these species females are usually more

aggressive, brightly colored, and larger than males, suggesting the more investing sex has more choice while selecting a mate compared to the sex engaged in intra-sexual selection.

Females as a valuable resource for males

The

second prediction that follows from Trivers' theory is that the fact

that women invest more heavily in offspring makes them a valuable

resource for males as it ensures the survival of their offspring which

is the driving force of

natural selection.

Therefore, the sex that invests less in offspring will compete among

themselves to breed with the more heavily investing sex. In other words,

males will compete for females.

It has been argued that

jealousy has developed to avert the risk of potential loss of parental investment in offspring.

If a male redirects his resources to another female it is a

costly loss of time, energy and resources for her offspring. However,

the risks for males are higher because although women invest more in

their offspring, they have bigger maternity certainty because they

themselves have carried out the child. However, males can never have

100% paternal certainty and therefore risk investing resources and time

in offspring that is genetically unrelated.

Evolutionary psychology views jealousy as an

adaptive response to this problem.

Application of Trivers' theory in real life

Trivers'

theory has been very influential as the predictions it makes correspond

to differences in sexual behaviors of men and women, as demonstrated by

a variety of research.

Cross-cultural study from

Buss (1989)

shows that males are tuned into physical attractiveness as it signals

youth and fertility and ensures male reproductive success, which is

increased by copulating with as many fertile females as possible. Women

on the other hand are tuned into resources provided by potential mates,

as their reproductive success is increased by ensuring their offspring

will survive, and one way they do so is by getting resources for them.

Alternatively, another study shows that men are more promiscuous than

women, giving further support to this theory. Clark and Hatfield

found that 75% of men were willing to have sex with a female stranger

when propositioned, compared to 0% of women. On the other hand, 50% of

women agreed to a date with a male stranger. This suggests males seek

short term relationships, while women show a strong preference for

long-term relationships.

However, these preferences (male promiscuity and female

choosiness) can be explained in other ways. In Western cultures, male

promiscuity is encouraged through the availability of pornographic

magazines and videos targeted to the male audience. Alternatively, both

Western and Eastern cultures discourage female promiscuity through

social checks such as

slut-shaming.

PIT (Parental Investment Theory) also explains patterns of

sexual jealousy.

Males are more likely to show a stress response when imagining their

partners showing sexual infidelity (having sexual relations with someone

else), and women showed more stress when imagining their partner being

emotionally unfaithful (being in love with another woman). PIT explains

this, as woman's sexual infidelity decreases the male's paternal

certainty, thus he will show more stress due to fear of

cuckoldry.

On the other hand, the woman fears losing the resources her partner

provides. If her partner has an emotional attachment to another female

it's likely that he won't invest into their offspring as much, thus a

greater stress response is shown in this circumstance.

A heavy criticism of the theory comes from Thornhill and Palmer's analysis of it in

A Natural History of Rape: Biological Bases of Sexual Coercion, as it seems to rationalize rape and

sexual coercion

of females. Thornhill and Palmer claimed rape is an evolved technique

for obtaining mates in an environment where women choose mates. As PIT

claims males seek to copulate with as many fertile females as possible,

the choice women have could result in a negative effect on the male's

reproductive success. If women didn't choose their mates, Thornhill and

Palmer claim there would be no rape. This ignores a variety of

sociocultural factors, such as the fact that not only fertile females

are raped – 34% of underage rape victims are under 12,

which means they are not of fertile age, thus there is no evolutionary

advantage in raping them. 14% of rapes in England are committed on

males,

who cannot increase a man's reproductive success as there will be no

conception. Thus, what Thornhill and Palmer called an 'evolved

machinery' might not be very advantageous.

Versus sexual strategies

Trivers'

theory overlooks that women do have short-term relationships such as

one-night stands, while not all men behave promiscuously. An alternative

explanation to PIT (Parental Investment Theory) and mate preferences

would be Buss and Schmitt's sexual strategies theory.

SST argues that both sexes pursue short-term and long-term

relationships, but seek different qualities in their short- and

long-term partners. For a short-term relationship women will prefer an

attractive partner, but in a long-term relationship they might be

willing to trade-off that attractiveness for resources and commitment.

On the other hand, men might be accepting of a sexually willing partner

in a short-term relationships, but to ensure their paternal certainty

they will seek a faithful partner instead.

International politics

Parental

investment theory is not only used to explain evolutionary phenomena

and human behavior but describes recurrences in international politics

as well. Specifically, parental investment is referred to when

describing competitive behaviors between states and determining

aggressive nature of foreign policies. The parental investment

hypothesis states that the size of coalitions and the physical strengths

of its male members determines whether its activities with its foreign

neighbors are aggressive or amiable.

According to Trivers, men have had relatively low parental investments,

and were therefore forced into fiercer competitive situations over

limited reproductive resources.

Sexual selection

naturally took place and men have evolved to address its unique

reproductive problems. Among other adaptations, men's psychology has

also developed to directly aid men in such intra-sexual competition.

One essential psychological developments involved decision-making

of whether to take flight or actively engage in warfare with another

rivalry group. The two main factors that men referred to in such

situations were (1) whether the coalition they are a part of is larger

than its opposition and (2) whether the men in their coalition have

greater physical strength than the other. The male psychology conveyed

in the ancient past has been passed on to modern times causing men to

partly think and behave as they have during ancestral wars. According to

this theory, leaders of international politics were not an exception.

For example, the United States expected to win the

Vietnam war

due to its greater military capacity when compared to its enemies. Yet

victory, according to the traditional rule of greater coalition size,

did not come about because the U.S. did not take enough consideration to

other factors, such as the perseverance of the local population.

The parental investment hypothesis contends that male physical

strength of a coalition still determines the aggressiveness of modern

conflicts between states. While this idea may seem unreasonable upon

considering that male physical strength is one of the least determining

aspects of today's warfare, human psychology has nevertheless evolved to

operate on this basis. Moreover, although it may seem that mate seeking

motivation is no longer a determinant, in modern wars sexuality, such

as rape, is undeniably evident in conflicts even to this day.

Sexual selection

In many species, males can produce a larger number of offspring over

the course of their lives by minimizing parental investment in favor of

investing time impregnating any reproductive-age female who is fertile.

In contrast, a female can have a much smaller number of offspring during

her reproductive life, partly due to higher obligate parental

investment. Females will be more selective ("choosy") of mates than

males will be, choosing males with good fitness (e.g., genes, high

status, resources, etc.), so as to help offset any lack of direct

parental investment from the male, and therefore increase reproductive

success.

Robert Trivers' theory of parental investment predicts that the

sex making the largest investment in

lactation, nurturing, and protecting offspring will be more discriminating in

mating; and that the sex that invests less in offspring will compete via

intrasexual selection for access to the higher-investing sex.

In species where both sexes invest highly in parental care,

mutual choosiness is expected to arise. An example of this is seen in

crested auklets,

where parents share equal responsibility in incubating their single egg

and raising the chick. In crested auklets both sexes are ornamented.

Parental investment in humans

Humans

have evolved increasing levels of parental investment, both

biologically and behaviorally. The fetus requires high investment from

the mother, and the altricial newborn requires high investment from a

community. Species whose newborn young are unable to move on their own

and require parental care have a high degree of

altriciality.

Human children are born unable to care for themselves and require

additional parental investment post-birth in order to survive.

Maternal investment

Trivers (1972)

hypothesized that greater biologically obligated investment will

predict greater voluntary investment. Mothers invest an impressive

amount in their children before they are even born. The time and

nutrients required to develop the fetus, and the risks associated with

both giving these nutrients and undergoing childbirth, are a sizable

investment. To ensure that this investment is not for nothing, mothers

are likely to invest in their children after they are born, to be sure

that they survive and are successful. Relative to most other species,

human mothers give more resources to their offspring at a higher risk to

their own health, even before the child is born. This is associated

with the evolution of a slower life history, in which fewer, larger

offspring are born after longer intervals, requiring increased parental

investment.

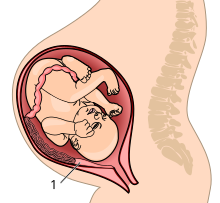

The placenta attaches to the uterine wall, and the umbilical cord connects it to the fetus.

The

developing human fetus––and especially the brain––requires nutrients to

grow. In the later weeks of gestation, the fetus requires increasing

nutrients as the growth of the brain increases.

Rodents and primates have the most invasive placenta phenotype, the

hemochorial placenta, in which the chorion erodes the uterine epithelium

and has direct contact with maternal blood. The other placental

phenotypes are separated from the maternal bloodstream by at least one

layer of tissue. The more invasive placenta allows for a more efficient

transfer of nutrients between the mother and fetus, but it comes with

risks as well. The fetus is able to release hormones directly into the

mother’s bloodstream to “demand” increased resources. This can result in

health problems for the mother, such as

pre-eclampsia. During childbirth, the detachment of the placental chorion can cause excessive bleeding.

The

obstetrical dilemma

also makes birth more difficult and results in increased maternal

investment. Humans have evolved both bipedalism and large brain size.

The evolution of bipedalism altered the shape of the pelvis, and shrunk

the birth canal at the same time brains were evolving to be larger. The

decreasing birth canal size meant that babies are born earlier in

development, when they have smaller brains. Humans give birth to babies

with brains 25% developed, while other primates give birth to offspring

with brains 45-50% developed.

A second possible explanation for the early birth in humans is the

energy required to grow and sustain a larger brain. Supporting a larger

brain gestationally requires energy the mother may be unable to invest.

The obstetrical dilemma makes birth challenging, and a

distinguishing trait of humans is the need for assistance during

childbirth. The altered shape of the bipedal pelvis requires that babies

leave the birth canal facing away from the mother, contrary to all

other primate species. This makes it more difficult for the mother to

clear the baby’s breathing passageways, to make sure the umbilical cord

isn’t wrapped around the neck, and to pull the baby free without bending

its body the wrong way.

The human need to have a birth attendant also requires

sociality.

In order to guarantee the presence of a birth attendant, humans must

aggregate in groups. It has been controversially claimed that humans

have

eusociality,

like ants and bees, in which there is relatively high parental

investment, cooperative care of young, and division of labor. It is

unclear which evolved first; sociality, bipedalism, or birth attendance.

Bonobos, our closest living relatives alongside chimpanzees, have high

female sociality and births among bonobos are also social events.

Sociality may have been a prerequisite for birth attendance, and

bipedalism and birth attendance could have evolved as long as five

million years ago.

A baby, mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. In humans, grandparents often help to raise a child.

As female primates age, their ability to reproduce decreases. The

grandmother hypothesis describes the evolution of menopause, which may or may not be unique to humans among primates.

As women age, the costs of investing in additional reproduction

increase and the benefits decrease. At menopause, it is more beneficial

to stop reproduction and begin investing in grandchildren. Grandmothers

are certain of their genetic relation to their grandchildren, especially

the children of their daughters, because maternal certainty of their

own children is high, and their daughters are certain of their maternity

to their children as well. It has also been theorized that grandmothers

preferentially invest in the daughters of their daughters because X

chromosomes carry more DNA and their granddaughters are most closely

related to them.

Paternal investment

As altriciality increased, investment from individuals other than the

mother became more necessary. High sociality meant that female

relatives were present to help the mother, but paternal investment

increased as well. Paternal investment increases as it becomes more

difficult to have additional children, and as the effects of investment

on offspring fitness increase.

Men are more likely than women to give no parental investment to

their children, and the children of low-investing fathers are more

likely to give less parental investment to their own children. Father

absence is a risk factor for both early sexual activity and teenage

pregnancy.

Father absence raises children's stress levels, which are linked to

earlier onset of sexual activity and increased short-term mating

orientation.

Daughters of absent fathers are more likely to seek short-term

partners, and one theory explains this as a preference for outside

(non-partner) social support because of the perceived uncertain future

and uncertain availability of committing partners in a high-stress

environment.

Investment as predictor of mating strategies

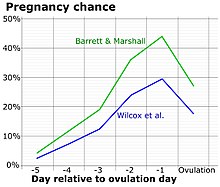

Concealed ovulation

Women can only get pregnant while ovulating. Human ovulation is

concealed, or not signaled externally. Concealed ovulation decreases

paternity certainty because men are unsure when women ovulate.

The evolution of concealed ovulation has been theorized to be a result

of altriciality and increased need for paternal investment. There are

two ways this could be true. First, if men are unsure of the time of

ovulation, the best way to successfully reproduce would be to repeatedly

mate with a woman throughout her cycle, which requires pair bonding,

which in turn increases paternal investment.

The second theory states that decreased paternity certainty would

increase paternal investment in polygamous groups, because more men may

invest in the offspring. The second theory is better regarded today,

because all mammals with concealed ovulation are promiscuous, and men

display relatively low mate-guarding behavior, as monogamy and the first

theory require.

Mating orientations

Sociosexuality was first described by

Alfred Kinsey as a willingness to engage in casual and uncommitted sexual relationships.

Sociosexual orientation describes sociosexuality on a scale from

unrestricted to restricted. Individuals with an unrestricted sociosexual

orientation have higher openness to sex in less committed

relationships, and individuals with a restricted sociosexual orientation

have lower openness to casual sexual relationships.

However, today it is acknowledged that sociosexuality does not in

reality exist on a one-dimensional scale. Individuals who are less open

to casual relationships are not always seeking committed relationships,

and individuals who are less interested in committed relationships are

not always interested in casual relationships.

Short- and long-term mating orientations are the modern descriptors of

openness to uncommitted and committed relationships, respectively.

Parental investment theory, as proposed by Trivers, argues that

the sex with higher obligatory investment will be more selective in

choosing sex partners, and the sex with lower obligatory investment will

be less selective and more interested in "casual" mating opportunities.

The more investing sex cannot reproduce as frequently, causing the less

investing sex to compete for mating opportunities. In humans, women have higher obligatory investment (

pregnancy and childbirth), than men (

sperm production).

Women are more likely to have higher long-term mating orientations, and

men are more likely to have higher short-term mating orientations.

Short- and long-term mating orientations influence women's

preferences in men. Studies have found that women put great emphasis on

career-orientation, ambition and devotion only when considering a

long-term partner. When marriage is not involved, women put greater emphasis on physical attractiveness.

Generally, women prefer men who are likely to perform high parental

investment and have good genes. Women prefer men with good financial

status, who are more committed, who are more athletic, and who are

healthier.

Some inaccurate theories have been inspired by parental investment theory. The "structural powerlessness hypothesis"

proposes that women strive to find mates with access to high levels of

resources because as women, they are excluded from these resources

directly. However, this hypothesis has been disproved by studies which

found that financially successful women place an even greater importance

on financial status, social status, and possession of professional

degrees.

Humans are sexually dimorphic; the average man is taller than the average woman.

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the difference in body size between male and

female members of a species as a result of intrasexual selection, which

is

sexual selection that acts within a sex. High sexual dimorphism and larger body size in males is a result of male-male competition for females.

Primate species in which groups are formed of many females and one male

have higher sexual dimorphism than species that have both multiple

females and males, or one female and one male. Polygynous primates have

the highest sexual dimorphism, and polygamous and monogamous primates

have less.

Humans have the lowest levels of sexual dimorphism of any primate

species, indicating that we have evolved decreasing levels of polygyny.

Decreased polygyny is associated with increased paternal investment.

The demographic transition

The

demographic transition

describes the modern decrease in both birth and death rates. From a

Darwinian perspective, it does not make sense that families with more

resources are having fewer children. One explanation for the demographic

transition is the increased parental investment required to raise

children who will be able to maintain the same level of resources as

their parents.