Stellar evolution

Condensed from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Artist's depiction of the life cycle of a Sun-like star, starting as a main-sequence star at lower left then expanding through the subgiant and giant phases, until its outer envelope is expelled to form a planetary nebula at upper right.

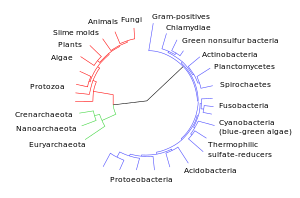

Stellar evolution is the process by which a star undergoes a sequence of radical changes during its lifetime. Depending on the mass of the star, this lifetime ranges from only a few million years for the most massive to trillions of years for the least massive, which is considerably longer than the age of the universe. The table shows the lifetimes of stars as a function of their masses.[1] All stars are born from collapsing clouds of gas and dust, often called nebulae or molecular clouds. Over the course of millions of years, these protostars settle down into a state of equilibrium, becoming what is known as a main-sequence star.

Nuclear fusion powers a star for most of its life. Initially the energy is generated by the fusion of hydrogen atoms at the core of the main-sequence star. Later, as the preponderance of atoms at the core becomes helium, stars like the Sun begin to fuse hydrogen along a spherical shell surrounding the core. This process causes the star to gradually grow in size, passing through the subgiant stage until it reaches the red giant phase. Stars with at least half the mass of the Sun can also begin to generate energy through the fusion of helium at their core, whereas more massive stars can fuse heavier elements along a series of concentric shells. Once a star like the Sun has exhausted its nuclear fuel, its core collapses into a dense white dwarf and the outer layers are expelled as a planetary nebula. Stars with around ten or more times the mass of the Sun can explode in a supernova as their inert iron cores collapse into an extremely dense neutron star or black hole. Although the universe is not old enough for any of the smallest red dwarfs to have reached the end of their lives, stellar models suggest they will slowly become brighter and hotter before running out of hydrogen fuel and becoming low-mass white dwarfs.[2]

Stellar evolution is not studied by observing the life of a single star, as most stellar changes occur too slowly to be detected, even over many centuries. Instead, astrophysicists come to understand how stars evolve by observing numerous stars at various points in their lifetime, and by simulating stellar structure using computer models.

Birth of a star

Protostar

Stellar evolution begins with the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud. Typical giant molecular clouds are roughly 100 light-years (9.5×1014 km) across and contain up to 6,000,000 solar masses (1.2×1037 kg). As it collapses, a giant molecular cloud breaks into smaller and smaller pieces. In each of these fragments, the collapsing gas releases gravitational potential energy as heat.As its temperature and pressure increase, a fragment condenses into a rotating sphere of superhot gas known as a protostar.[3]

The further development heavily depends on the mass of the evolving protostar; in the following, The protostar mass is compared to the mass of the Sun: 1.0 M☉ (2.0×1030 kg) means 1 solar mass.

Protostars are encompassed in dust, and are thus more readily visible at infrared wavelengths. Observations from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have been especially important for unveiling numerous Galactic protostars and their parent star clusters.[4][5]

Brown dwarfs and sub-stellar objects

Protostars with masses less than roughly 0.08 M☉ (1.6×1029 kg) never reach temperatures high enough for nuclear fusion of hydrogen to begin. These are known as brown dwarfs. The International Astronomical Union defines brown dwarfs as stars massive enough to fuse deuterium at some point in their lives (13 Jupiter masses, 2.5 × 1028 kg, or 0.0125 solar masses). Objects smaller than 13 Jupiter masses are classified as sub-brown dwarfs (but if they orbit around another stellar object they are classified as planets).[6] Both types, deuterium-burning and not, shine dimly and die away slowly, cooling gradually over hundreds of millions of years.Hydrogen fusion

For a more massive protostar, the core temperature will eventually reach 10 million kelvin, initiating the proton-proton chain reaction and allowing hydrogen to fuse, first to deuterium and then to helium. In stars of slightly over 1 M☉ (2.0×1030 kg), the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen fusion reaction (CNO cycle) contributes a large portion of the energy generation. The onset of nuclear fusion leads relatively quickly to a hydrostatic equilibrium in which energy released by the core exerts a "radiation pressure" balancing the weight of the star's matter, preventing further gravitational collapse. The star thus evolves rapidly to a stable state, beginning the main-sequence phase of its evolution.

A new star will sit at a specific point on the main sequence of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, with the main-sequence spectral type depending upon the mass of the star. Small, relatively cold, low-mass red dwarfs fuse hydrogen slowly and will remain on the main sequence for hundreds of billions of years or longer, whereas massive, hot supergiants will leave the main sequence after just a few million years. A mid-sized star like the Sun will remain on the main sequence for about 10 billion years. The Sun is thought to be in the middle of its lifespan; thus, it is currently on the main sequence.

The evolutionary tracks of stars with different initial masses on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. The tracks start once the star has evolved to the main sequence and stop when fusion stops.

A yellow track is shown for the Sun, which will become a red giant after its main-sequence phase ends before expanding further along the asymptotic giant branch, which will be the last phase in which the Sun undergoes fusion.

A yellow track is shown for the Sun, which will become a red giant after its main-sequence phase ends before expanding further along the asymptotic giant branch, which will be the last phase in which the Sun undergoes fusion.

Mature stars

Eventually the core exhausts its supply of hydrogen and the star begins to evolve off of the main sequence. Without the outward pressure generated by the fusion of hydrogen to counteract the force of gravity the core contracts until either electron degeneracy becomes sufficient to oppose gravity or the core becomes hot enough (around 100 MK) for helium fusion to begin. Which of these happens first depends upon the star's mass.Low-mass stars

What happens after a low-mass star ceases to produce energy through fusion has not been directly observed; the universe is thought to be around 13.8 billion years old, which is less time (by several orders of magnitude, in some cases) than it takes for fusion to cease in such stars.Recent astrophysical models suggest that red dwarfs of 0.1 solar mass may stay on the main sequence for some six to twelve trillion years, gradually increasing in both temperature and luminosity, and take several hundred billion more to slowly collapse into a white dwarf.[7][8] Such stars are fully convective and will not develop a degenerate helium core with hydrogen burning shells, or at least not until almost the whole star is helium, so they don't ever expand into a red giant.

Slightly more massive stars do expand into red giants, but their helium cores are not massive enough to ever reach the temperatures required for helium fusion so they never reach the tip of the red giant branch. When hydrogen shell burning finishes, these stars move directly off the red giant branch like a post AGB star, but at lower luminosity, to become a white dwarf.[2] A star of about 0.5 solar mass will be able to reach temperatures high enough to fuse helium, and these "mid-sized" stars go on to further stages of evolution beyond the red giant branch.

Mid-sized stars

Internal structures of main-sequence stars, convection zones with arrowed cycles and radiative zones with red flashes. To the left a low-mass red dwarf, in the center a mid-sized yellow dwarf and at the right a massive blue-white main-sequence star.

The Cat's Eye Nebula, a planetary nebula formed by the death of a star with about the same mass as the Sun

Stars of roughly 0.5–10 solar masses become red giants, which are large non-main-sequence stars of stellar classification K or M. Red giants lie along the right edge of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram due to their red color and large luminosity. Examples include Aldebaran in the constellation Taurus and Arcturus in the constellation of Boötes. Red giants all have inert cores with hydrogen-burning shells: concentric layers atop the core that are still fusing hydrogen into helium.

Mid-sized stars are red giants during two different phases of their post-main-sequence evolution: red-giant-branch stars, whose inert cores are made of helium, and asymptotic-giant-branch stars, whose inert cores are made of carbon. Asymptotic-giant-branch stars have helium-burning shells inside the hydrogen-burning shells, whereas red-giant-branch stars have hydrogen-burning shells only.[9] In either case, the accelerated fusion in the hydrogen-containing layer immediately over the core causes the star to expand. This lifts the outer layers away from the core, reducing the gravitational pull on them, and they expand faster than the energy production increases. This causes the outer layers of the star to cool, which causes the star to become redder than it was on the main sequence.

Red-giant-branch phase

The red-giant-branch phase of a star's life follows the main sequence. Initially, the cores of red-giant-branch stars collapse, as the internal pressure of the core is insufficient to balance gravity. This gravitational collapse releases energy, heating concentric shells immediately outside the inert helium core so that hydrogen fusion continues in these shells. The core of a red-giant-branch star of up to a few solar masses stops collapsing when it is dense enough to be supported by electron degeneracy pressure. Once this occurs, the core reaches hydrostatic equilibrium: the electron degeneracy pressure is sufficient to balance gravitational pressure.[10] The core's gravity compresses the hydrogen in the layer immediately above it, causing it to fuse faster than hydrogen would fuse in a main-sequence star of the same mass. This in turn causes the star to become more luminous (from 1,000–10,000 times brighter) and expand; the degree of expansion outstrips the increase in luminosity, causing the effective temperature to decrease.The expanding outer layers of the star are convective, with the material being mixed by turbulence from near the fusing regions up to the surface of the star. For all but the lowest-mass stars, the fused material has remained deep in the stellar interior prior to this point, so the convecting envelope makes fusion products visible at the star's surface for the first time. At this stage of evolution, the results are subtle, with the largest effects, alterations to the isotopes of hydrogen and helium, being unobservable. The effects of the CNO cycle appear at the surface, with lower 12C/13C ratios and altered proportions of carbon and nitrogen. These are detectable with spectroscopy and have been measured for many evolved stars.

As the hydrogen around the core is consumed, the core absorbs the resulting helium, causing it to contract further, which in turn causes the remaining hydrogen to fuse even faster. This eventually leads to ignition of helium fusion (which includes the triple-alpha process) in the core. In stars of more than approximately solar mass, it can take a billion years or more for the core to reach helium ignition temperatures.

When the temperature and pressure in the core become sufficient to ignite helium fusion, a helium flash will occur if the core is largely supported by electron degeneracy pressure (stars under 1.4 solar mass). In more massive stars, the ignition of helium fusion occurs relatively quietly. Even if a helium flash does occur, the time of very rapid energy release (on the order of 108 Suns) is brief, so that the visible outer layers of the star are relatively undisturbed.[11] The energy released by helium fusion causes the core to expand, so that hydrogen fusion in the overlying layers slows and total energy generation decreases. The star contracts, although not all the way to the main sequence, and it migrates to the horizontal branch on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, gradually shrinking in radius and increasing its surface temperature. Core helium flash stars evolve to the red end of the horizontal branch but do not migrate to higher temperatures before they gain a degenerate carbon-oxygen core and start helium shell burning. These stars are often observed as a red clump of stars in the colour-magnitude diagram of a cluster, hotter and less luminous than the red giants. Higher-mass stars with larger helium cores move along the horizontal branch to higher temperatures, some becoming unstable pulsating stars in the yellow instability strip (RR Lyrae variables), whereas some become even hotter and can form a blue tail or blue hook to the horizontal branch. The exact morphology of the horizontal branch depends on parameters such as metallicity, age, and helium content, but the exact details are still being modelled.[12]

Asymptotic-giant-branch phase

After a star has consumed the helium at the core, fusion continues in a shell around a hot core of carbon and oxygen. The star follows the asymptotic giant branch on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, paralleling the original red giant evolution, but with even faster energy generation (which lasts for a shorter time).[13] Although helium is being burnt in a shell, the majority of the energy is produced by hydrogen burning in a shell closer to the surface of the star. Helium from these hydrogen burning shells drops towards the center of the star and periodically the energy output from the helium shell increases dramatically. This is known as a thermal pulse and they occur towards the end of the asymptotic-giant-branch phase, sometimes even into the post-asymptotic-giant-branch phase.Depending on mass and composition, there may be several to hundreds of thermal pulses.

There is a phase on the ascent of the asymptotic-giant-branch where a deep convective zone forms and can bring carbon from the core to the surface, This is known as the second dredge up, and in some stars there may even be a third dredge up. In this way a carbon star is formed, very cool and strongly reddened stars showing strong carbon lines in their spectra. A process known as hot bottom burning may convert carbon into oxygen and nitrogen before it can be dredged to the surface, and the interaction between these processes determines the observed luminosities and spectra of carbon stars in particular clusters.[14]

Another well known class of asymptotic-giant-branch stars are the Mira variables, which pulsate with well-defined periods of tens to hundreds of days and large amplitudes up to about 10 magnitudes (in the visual, total luminosity changes by a much smaller amount). In more massive stars the stars become more luminous and the pulsation period is longer, leading to enhanced mass loss, and the stars become heavily obscured at visual wavelengths. These stars can be observed as OH/IR stars, pulsating in the infra-red and showing OH maser activity. These stars are clearly oxygen rich, in contrast to the carbon stars, but both must be produced by dredge ups.

These mid-range stars ultimately reach the tip of the asymptotic-giant-branch and run out of fuel for shell burning. They are not sufficiently massive to start full-scale carbon fusion, so they contract again, going through a period of post-asymptotic-giant-branch superwind to produce a planetary nebula with an extremely hot central star. The central star then cools to a white dwarf. The expelled gas is relatively rich in heavy elements created within the star and may be particularly oxygen or carbon enriched, depending on the type of the star. The gas builds up in an expanding shell called a circumstellar envelope and cools as it moves away from the star, allowing dust particles and molecules to form. With the high infrared energy input from the central star, ideal conditions are formed in these circumstellar envelopes for maser excitation.

It is possible for thermal pulses to be produced once post-asymptotic-giant-branch evolution has begun, producing a variety of unusual and poorly understood stars known as born-again asymptotic-giant-branch stars.[15] These may result in extreme horizontal-branch stars (subdwarf B stars), hydrogen deficient post-asymptotic-giant-branch stars, variable planetary nebula central stars, and R Coronae Borealis variables.

Massive stars

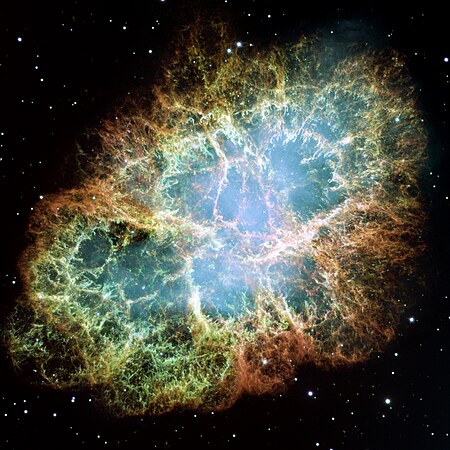

The Crab Nebula, the shattered remnants of a star which exploded as a supernova, the light of which reached Earth in 1054 AD

In massive stars, the core is already large enough at the onset of the hydrogen burning shell that helium ignition will occur before electron degeneracy pressure has a chance to become prevalent.

Thus, when these stars expand and cool, they do not brighten as much as lower-mass stars; however, they were much brighter than lower-mass stars to begin with, and are thus still brighter than the red giants formed from less massive stars. These stars are unlikely to survive as red supergiants; instead they will destroy themselves as type II supernovas.

Extremely massive stars (more than approximately 40 solar masses), which are very luminous and thus have very rapid stellar winds, lose mass so rapidly due to radiation pressure that they tend to strip off their own envelopes before they can expand to become red supergiants, and thus retain extremely high surface temperatures (and blue-white color) from their main-sequence time onwards.

The largest stars of the current generation are about 100-150 solar masses because the outer layers would be expelled by the extreme radiation. Although lower-mass stars normally do not burn off their outer layers so rapidly, they can likewise avoid becoming red giants or red supergiants if they are in binary systems close enough so that the companion star strips off the envelope as it expands, or if they rotate rapidly enough so that convection extends all the way from the core to the surface, resulting in the absence of a separate core and envelope due to thorough mixing.[16]

The core grows hotter and denser as it gains material from fusion of hydrogen at the base of the envelope. In all massive stars, electron degeneracy pressure is insufficient to halt collapse by itself, so as each major element is consumed in the center, progressively heavier elements ignite, temporarily halting collapse. If the core of the star is not too massive (less than approximately 1.4 solar mass, taking into account mass loss that has occurred by this time), it may then form a white dwarf (possibly surrounded by a planetary nebula) as described above for less massive stars, with the difference that the white dwarf is composed chiefly of oxygen, neon, and magnesium.

Above a certain mass (estimated at approximately 2.5 solar masses and whose star's progenitor was around 10 solar masses), the core will reach the temperature (approximately 1.1 gigakelvins) at which neon partially breaks down to form oxygen and helium, the latter of which immediately fuses with some of the remaining neon to form magnesium; then oxygen fuses to form sulfur, silicon, and smaller amounts of other elements. Finally, the temperature gets high enough that any nucleus can be partially broken down, most commonly releasing an alpha particle (helium nucleus) which immediately fuses with another nucleus, so that several nuclei are effectively rearranged into a smaller number of heavier nuclei, with net release of energy because the addition of fragments to nuclei exceeds the energy required to break them off the parent nuclei.

A star with a core mass too great to form a white dwarf but insufficient to achieve sustained conversion of neon to oxygen and magnesium, will undergo core collapse (due to electron capture) before achieving fusion of the heavier elements.[17] Both heating and cooling caused by electron capture onto minor constituent elements (such as aluminum and sodium) prior to collapse may have a significant impact on total energy generation within the star shortly before collapse.[18] This may produce a noticeable effect on the abundance of elements and isotopes ejected in the subsequent supernova.

Supernova

Once the nucleosynthesis process arrives at iron-56, the continuation of this process consumes energy (the addition of fragments to nuclei releases less energy than required to break them off the parent nuclei). If the mass of the core exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit, electron degeneracy pressure will be unable to support its weight against the force of gravity, and the core will undergo sudden, catastrophic collapse to form a neutron star or (in the case of cores that exceed the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit), a black hole. Through a process that is not completely understood, some of the gravitational potential energy released by this core collapse is converted into a Type Ib, Type Ic, or Type II supernova. It is known that the core collapse produces a massive surge of neutrinos, as observed with supernova SN 1987A. The extremely energetic neutrinos fragment some nuclei; some of their energy is consumed in releasing nucleons, including neutrons, and some of their energy is transformed into heat and kinetic energy, thus augmenting the shock wave started by rebound of some of the infalling material from the collapse of the core. Electron capture in very dense parts of the infalling matter may produce additional neutrons. Because some of the rebounding matter is bombarded by the neutrons, some of its nuclei capture them, creating a spectrum of heavier-than-iron material including the radioactive elements up to (and likely beyond) uranium.[19] Although non-exploding red giants can produce significant quantities of elements heavier than iron using neutrons released in side reactions of earlier nuclear reactions, the abundance of elements heavier than iron (and in particular, of certain isotopes of elements that have multiple stable or long-lived isotopes) produced in such reactions is quite different from that produced in a supernova. Neither abundance alone matches that found in the Solar System, so both supernovae and ejection of elements from red giants are required to explain the observed abundance of heavy elements and isotopes there of.The energy transferred from collapse of the core to rebounding material not only generates heavy elements, but provides for their acceleration well beyond escape velocity, thus causing a Type Ib, Type Ic, or Type II supernova. Note that current understanding of this energy transfer is still not satisfactory; although current computer models of Type Ib, Type Ic, and Type II supernovae account for part of the energy transfer, they are not able to account for enough energy transfer to produce the observed ejection of material.[20] Some evidence gained from analysis of the mass and orbital parameters of binary neutron stars (which require two such supernovae) hints that the collapse of an oxygen-neon-magnesium core may produce a supernova that differs observably (in ways other than size) from a supernova produced by the collapse of an iron core.[21]

The most massive stars that exist today may be completely destroyed by a supernova with an energy greatly exceeding its gravitational binding energy. This rare event, caused by pair-instability, leaves behind no black hole remnant.[22] In the past history of the universe, some stars were even larger than the largest that exists today, and they would immediately collapse into a black hole at the end of their lives, due to photodisintegration.

Stellar remnants

After a star has burned out its fuel supply, its remnants can take one of three forms, depending on the mass during its lifetime.White and black dwarfs

For a star of 1 solar mass, the resulting white dwarf is of about 0.6 solar mass, compressed into approximately the volume of the Earth. White dwarfs are stable because the inward pull of gravity is balanced by the degeneracy pressure of the star's electrons, a consequence of the Pauli exclusion principle. Electron degeneracy pressure provides a rather soft limit against further compression; therefore, for a given chemical composition, white dwarfs of higher mass have a smaller volume.With no fuel left to burn, the star radiates its remaining heat into space for billions of years.

A white dwarf is very hot when it first forms, more than 100,000 K at the surface and even hotter in its interior. It is so hot that a lot of its energy is lost in the form of neutrinos for the first 10 million years of its existence, but will have lost most of its energy after a billion years.[23]

The chemical composition of the white dwarf depends upon its mass. A star of a few solar masses will ignite carbon fusion to form magnesium, neon, and smaller amounts of other elements, resulting in a white dwarf composed chiefly of oxygen, neon, and magnesium, provided that it can lose enough mass to get below the Chandrasekhar limit (see below), and provided that the ignition of carbon is not so violent as to blow the star apart in a supernova.[24] A star of mass on the order of magnitude of the Sun will be unable to ignite carbon fusion, and will produce a white dwarf composed chiefly of carbon and oxygen, and of mass too low to collapse unless matter is added to it later (see below). A star of less than about half the mass of the Sun will be unable to ignite helium fusion (as noted earlier), and will produce a white dwarf composed chiefly of helium.

In the end, all that remains is a cold dark mass sometimes called a black dwarf. However, the universe is not old enough for any black dwarfs to exist yet.

If the white dwarf's mass increases above the Chandrasekhar limit, which is 1.4 solar mass for a white dwarf composed chiefly of carbon, oxygen, neon, and/or magnesium, then electron degeneracy pressure fails due to electron capture and the star collapses. Depending upon the chemical composition and pre-collapse temperature in the center, this will lead either to collapse into a neutron star or runaway ignition of carbon and oxygen. Heavier elements favor continued core collapse, because they require a higher temperature to ignite, because electron capture onto these elements and their fusion products is easier; higher core temperatures favor runaway nuclear reaction, which halts core collapse and leads to a Type Ia supernova.[25] These supernovae may be many times brighter than the Type II supernova marking the death of a massive star, even though the latter has the greater total energy release. This inability to collapse means that no white dwarf more massive than approximately 1.4 solar mass can exist (with a possible minor exception for very rapidly spinning white dwarfs, whose centrifugal force due to rotation partially counteracts the weight of their matter). Mass transfer in a binary system may cause an initially stable white dwarf to surpass the Chandrasekhar limit.

If a white dwarf forms a close binary system with another star, hydrogen from the larger companion may accrete around and onto a white dwarf until it gets hot enough to fuse in a runaway reaction at its surface, although the white dwarf remains below the Chandrasekhar limit. Such an explosion is termed a nova.

Neutron stars

When a stellar core collapses, the pressure causes electron capture, thus converting the great majority of the protons into neutrons. The electromagnetic forces keeping separate nuclei apart are gone (proportionally, if nuclei were the size of dust mites, atoms would be as large as football stadiums), and most of the core of the star becomes a dense ball of contiguous neutrons (in some ways like a giant atomic nucleus), with a thin overlying layer of degenerate matter (chiefly iron unless matter of different composition is added later). The neutrons resist further compression by the Pauli Exclusion Principle, in a way analogous to electron degeneracy pressure, but stronger.

These stars, known as neutron stars, are extremely small—on the order of radius 10 km, no bigger than the size of a large city—and are phenomenally dense. Their period of rotation shortens dramatically as the stars shrink (due to conservation of angular momentum); observed rotational periods of neutron stars range from about 1.5 milliseconds (over 600 revolutions per second) to several seconds.[26] When these rapidly rotating stars' magnetic poles are aligned with the Earth, we detect a pulse of radiation each revolution. Such neutron stars are called pulsars, and were the first neutron stars to be discovered. Though electromagnetic radiation detected from pulsars is most often in the form of radio waves, pulsars have also been detected at visible, X-ray, and gamma ray wavelengths.[27]

Black holes

If the mass of the stellar remnant is high enough, the neutron degeneracy pressure will be insufficient to prevent collapse below the Schwarzschild radius. The stellar remnant thus becomes a black hole. The mass at which this occurs is not known with certainty, but is currently estimated at between 2 and 3 solar masses.Black holes are predicted by the theory of general relativity. According to classical general relativity, no matter or information can flow from the interior of a black hole to an outside observer, although quantum effects may allow deviations from this strict rule. The existence of black holes in the universe is well supported, both theoretically and by astronomical observation.

Because the core-collapse supernova mechanism itself is imperfectly understood, it is still not known whether it is possible for a star to collapse directly to a black hole without producing a visible supernova, or whether some supernovae initially form unstable neutron stars which then collapse into black holes; the exact relation between the initial mass of the star and the final remnant is also not completely certain. Resolution of these uncertainties requires the analysis of more supernovae and supernova remnants.