We are the 99% is a political slogan widely used and coined during the 2011 Occupy movement from Gore Vidal's famous and original version "the one percent", meaning the nation's wealthiest 1%, to which the 99% reversely correspond.

The phrase directly refers to the income and wealth inequality in the United States with a concentration of wealth among the top-earning 1%. It reflects an opinion that "the 99%" are paying the price for the mistakes of a tiny minority within the upper class.

According to the Economic Policy Institute as of 2018, all households with incomes less than $737,697 belonged to the lower 99% of wage earners. However, the 1% is not necessarily a reference to top 1% of wage earners, but a reference to the top 1% of individuals by net worth, of which earned wages are only a fraction of the many factors that contribute to their wealth.

Origin

Mainstream accounts

The slogan "We are the 99%" became a unifying slogan of the Occupy movement in August 2011 after a Tumblr blog "wearethe99percent.tumblr.com" was launched in late August 2011 by a 28-year-old New York activist going by the name of "Chris" together with Priscilla Grim.

Chris credited an August 2011 flyer for the NYC assembly "We The 99%" for the term. A 2011 Rolling Stone article attributed to anthropologist David Graeber the suggestion that the Occupy movement represented the 99%. Graeber was sometimes credited with the slogan "We are the 99%" but attributed the full version to others.

Mainstream media sources trace the origin of the phrase to economist Joseph Stiglitz's May 2011 article "Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%" in Vanity Fair, in which he was criticizing the economic inequality present in the United States. In the article Stiglitz spoke of the damaging impact of economic inequality involving 1% of the U.S. population owning a large portion of economic wealth in the country, while 99% of the population hold much less economic wealth than the richest 1%:

[I]n our democracy, 1% of the people take nearly a quarter of the nation's income … In terms of wealth rather than income, the top 1% control 40% … [as a result] the top 1% have the best houses, the best educations, the best doctors, and the best lifestyles, but there is one thing that money doesn't seem to have bought: an understanding that their fate is bound up with how the other 99% live. Throughout history, this is something that the top 1% eventually do learn. Too late.

Earlier uses of the term "the one percent" to refer to the wealthiest people in society include the 2006 documentary The One Percent (film) about the growing wealth gap between the wealthy elite compared to the overall population, and a 2001 opinion column in the MIT student newspaper The Tech (newspaper).

Other published accounts

More than one publication dates the concept back much further. For instance, the one percent and the 99 percent were explained in a February 1984 article titled "The USA: Who Owns It? Who Runs It?" in Black Liberation Month News, published in Chicago and available online as of 2020.

Even further back, historian Howard Zinn used this concept in "The Coming Revolt of the Guards", the final chapter in the first edition of his book A People's History of the United States published in 1980. "I am taking the liberty of uniting those 99 percent as 'the people'. I have been writing a history that attempts to represent their submerged, deflected, common interest. To emphasize the commonality of the 99 percent, to declare deep enmity of interest with the 1 percent, is to do exactly what the governments of the United States, and the wealthy elite allied to them-from the Founding Fathers to now-have tried their best to prevent."

The 1960 novel Too Many Clients by Rex Stout, part of the Nero Wolfe mystery series, refers to the top two percent: "I know a chairman of the board of a billion-dollar corporation, one of the 2 per cent, [sic] who never gets his shoes shined and shaves three times a week."

The first mention of the concept may very well be found in a poster (circa 1935) advertising the newspaper created by the populist Louisiana politician Huey Long called The American Progress. The second paragraph mentioned the one percent and the ninety-nine percent: "With 1% of our people owning nearly twice as much as all the other 99%, how is a country ever to have permanent progress unless there is a correction of this evil?"

Variations on the slogan

- "We are the 1 percent; we stand with the 99 percent": by members of the "one percent" who wish to express their support for higher taxes, such as nonprofit organizations Resource Generation and Wealth for the Common Good.

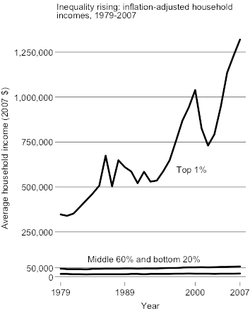

- "We are the 99.9%": by Nobel Prize–winning economist Paul Krugman in an op-ed in The New York Times arguing that the original slogan sets the bar too low when considering recent changes in distribution of income. In particular, Krugman cited a 2005 Congressional Budget Office report indicating that between 1979 and 2005 the inflation-adjusted income for the middle of the income distribution rose 21%, while for the top 0.1% it rose by 400%.

- "We are the 53%": by conservative RedState.com blogger Erick Erickson along with Josh Treviño, communications director for the Texas Public Policy Foundation, and filmmaker Mike Wilson launched in October 2011, in response to the 99% slogan. Erikson referred to the 53% of American workers who pay federal income taxes, and criticizing the 47% of workers who do not pay federal income tax for what Erikson describes as being "subsidized" by those who pay taxes. The Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution both reported that roughly half of the workers who do not pay Federal income tax earn below the tax threshold while the other half pay no income tax due to "provisions that benefit senior citizens and low-income working families with children."

- "We are the 48%": by those who supported the United Kingdom remaining in the European Union after the 2016 referendum on membership, highlighting the relatively even split between supporters of remaining in and withdrawing from the EU.

- "We are the 87%" (German language: "Wir Sind 87 Prozent") : by the German people who did not vote for the far-right Alternative for Germany party in the 2017 German federal election.

Economic context

"We are the 99%" is a political slogan and an implicit economic claim of "Occupy" protesters. It refers to the increased concentration of income and wealth since the 1970s among the top 1% of income earners in the United States.

It also reflects an opinion that the "99%" are paying the price for the mistakes of a tiny minority within the upper class.

Studies by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the US Department of Commerce, and Internal Revenue Service show that income inequality has grown significantly since the late 1970s, after several decades of stability. Between 1979 and 2007, the top earning 1 percent of Americans have seen their after-tax-and-benefit incomes grow by an average of 275%, compared to around 40–60% for the lower 99 percent. Since 1979 the average pre-tax income for the bottom 90% of households has decreased by $900, while that of the top 1% increased by over $700,000. This imbalance became further exacerbated by changes making federal income taxes less progressive. From 1992-2007 the top 400 income earners in the U.S. saw their income increase 392% and their average tax rate reduced by 37%. In 2009, the average income of the top 1% was $960,000 with a minimum income of $343,927. In 2007 the top 1% had a larger share of total income than at any time since 1928. This is in stark contrast with surveys of US populations that indicate an "ideal" distribution that is much more equal, and a widespread ignorance of the true income inequality and wealth inequality. In 2007, the richest 1% of the American population owned 34.6% of the country's total wealth, and the next 19% owned 50.5%. Thus, the top 20% of Americans owned 85% of the country's wealth and the bottom 80% of the population owned 15% in 2007. Financial inequality measured as the total net worth minus the value of one's home was greater than inequality in total wealth, with the top 1% of the population owning 42.7%, the next 19% of Americans owning 50.3%, and the bottom 80% owning 7% per Forbes in 2011. After the Great Recession started in 2007, the share of total wealth owned by the top 1% of the population grew from 34.6% to 37.1%, and that owned by the top 20% of Americans grew from 85% to 87.7%. Median household wealth dropped by 36.1% compared to a drop of only 11.1% for the top 1%, further widening the gap. During the economic expansion between 2002 and 2007, the income of the top 1% had grown 10 times faster than the income of the bottom 90% and 66% of total income gains went to the 1%.

According to the Economic Policy Institute as of 2018, all households with incomes less than $737,697 belonged to the lower 99% of wage earners.

Data on the minimum yearly income to be considered among the 1% vary per source, ranging from about $500,000 to $1.3 million. This is somewhat below the average compensation range of CEOs whose salaries average $3.9 million according to the AFL-CIO. CEOs salaries average $10.6 million for those whose companies are in the S&P 500 and $19.8 million for companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Following the recession of the late 2000s (decade), the economy in the US continued to experience a jobless recovery. New York Times columnist Anne-Marie Slaughter described pictures on the "We are the 99" website as "page after page of testimonials from members of the middle class who took out loans to pay for education, took out mortgages to buy their houses and a piece of the American dream, worked hard at the jobs they could find, and ended up unemployed or radically underemployed and on the precipice of financial and social ruin." With market uncertainty due to fears of a double-dip recession and the downgrade of the US credit rating in the summer of 2011, the topics of how much the rich pay in taxes and how to solve the nation's economic crisis dominated media commentary. When Congress returned from break, proposed policy solutions came from both major parties as the 2012 Republican presidential debates occurred almost simultaneously with President Obama's September 9 proposal of the American Jobs Act. On September 17, 2011 President Obama announced an economic policy proposal for taxing millionaires known as the Buffett Rule. This immediately led to public statements by House Speaker John Boehner, President Obama, and Republican Mitt Romney over whether the Democrats were fomenting "class warfare".

In November 2011 economist Paul Krugman wrote, that the We are the 99% slogan "correctly defines the issue as being the middle class versus the elite and also gets past the common but wrong notion that rising inequality is mainly about the well educated doing better than the less educated." He questioned whether the slogan ought to refer to the 99.9 percent, as a large fraction of the top 1 percent's gains have actually gone to an even smaller group, the top 0.1 percent—the richest one-thousandth of the population. Krugman argued against the idea that the very rich make a special contribution to the economy as "job creators" as few were new economy innovators like Steve Jobs. He quoted a recent analysis having found that 43% of the top 0.1 percent were executives at non-financial companies, 18% in finance, and another 12% are lawyers or in real estate. Commenting on the ongoing economic crisis he wrote, "[the] seemingly high returns before the crisis simply reflected increased risk-taking—risk that was mostly borne not by the wheeler-dealers themselves, but either by naïve investors or by taxpayers, who ended up holding the bag when it all went wrong".

In general, empirical researches have shown the accuracy of this slogan. Per an Oxfam report, just ahead of the 2015 World Economic Forum: "The combined wealth of the world's richest 1 percent will overtake that of everyone else by next year [2016] given the current trend of rising inequality".

Criticism

CNBC senior markets writer Jeff Cox reacted negatively to the protest movement, calling the 1% are "the most vilified members of American society" who protesters fail to realize includes not only corporate CEOs (31% of the top earning one percent), bankers and stock traders (13.9%), but also doctors (1.85%), real estate professionals (3.2%), entertainers in arts, media and sports (1.6%), professors and scientists (1.8%), lawyers (1.22%), farmers and ranchers (0.5%), and pilots (0.2%). Cox noted that 1 Percenters pay a disproportionate amount of their incomes to taxes, which later research has confirmed. He stated the phenomenon of wealth concentration among a small segment of the population is a century old, and argued a direct correlation between wealth concentration and the health of the stock market, stating that 36.7% of the United States' wealth was controlled by the 1% in 1922, 44.2% when the stock market crashed in 1929, 19.9% in 1976, and has increased since then. Cox wrote that wealth concentration intensified at the same time that the US changed from a manufacturing leader to a financial services leader. Cox took issue with protesters' focus on income and wealth, and with their embrace of rich allies such as actress Susan Sarandon and Russell Simmons, who are themselves in the 1%. Josh Barro of National Review offered similar arguments, asserting that the 1% includes those with incomes beginning at $593,000, which would exclude most Wall Street bankers.

Economist Thomas Sowell noted in November 2011 that IRS data shows the majority of those in the top 1% of income are there for a short period, and that age was more associated with wealth concentration than was income. Sowell further argued that analyzing data about abstract categories (like income brackets) should not be confused with analyzing data about individuals (who can move in and out of various abstract categories, like income brackets, throughout their lives):

- "It is easier and cheaper to collect statistics about income

brackets than it is to follow actual flesh-and-blood people as they move

massively from one income bracket to another over the years.

More important, statistical studies that follow particular individuals over the years often reach diametrically opposite conclusions from those reached by statistical studies that follow income brackets over the years."

Economic professor Sean Mulholland argued in 2012 that the idea that the richer have become richer while the poor have become poorer is false because data showing that the richest income earners grew significantly richer over the same period that members of poorer classes maintained a fairly constant income rate does not account for the upward and downward economic mobility of particular households over recent decades.

In the US, Republicans have generally been critical of the movement accusing protesters and their supporters of class warfare. Newt Gingrich called the "concept of the 99 and the one" both divisive and "un-American". Democrats have offered "cautious support", using the "99%" slogan to argue for the passage of President Obama's jobs act, Internet access rules, voter identification laws, mine safety, and other issues. Both parties agree that the movement has changed public debate. In December 2011, the New York Times reported that "Whatever the long-term effects of the Occupy Movement, protesters succeeded in implanting "we are the 99 percent" ... into the cultural and political lexicon."

New Continental Congress

After the Occupy movement activists' camps started getting uprooted, the Occupy movement came back online proposing a new United States Declaration of Independence from corporations, along with a new Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

See also

- 99 Percent Declaration

- 99ers

- Affluence in the United States

- American upper class

- Bank Transfer Day

- Basket of deplorables

- Distribution of wealth

- High-net-worth individual

- Household income in the United States

- How the Other Half Lives

- Income inequality in the United States

- Let Wall Street Pay for the Restoration of Main Street Bill

- Lobby 99

- Mitt Romney's 47% Comment

- Occupy movement

- Occupy Wall Street

- Oligarchy

- Plutocracy

- Two Americas

- Upper ten thousand

- Wealth in the United States

- Wealth inequality in the United States