From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

White flight or white exodus is the sudden or gradual large-scale migration of white people from areas becoming more racially or ethnoculturally diverse. Starting in the 1950s and 1960s, the terms became popular in the United States. They referred to the large-scale migration of people of various European ancestries from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions. The term has more recently been applied to other migrations by whites, from older, inner suburbs to rural areas, as well as from the U.S. Northeast and Midwest to the milder climate in the Southeast and Southwest. The term 'white flight' has also been used for large-scale post-colonial emigration of whites from Africa, or parts of that continent, driven by levels of violent crime and anti-colonial or anti-white state policies.

Migration of middle-class white populations was observed during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s out of cities such as Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City and Oakland, although racial segregation of public schools had ended there long before the Supreme Court of the United States' decision Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. In the 1970s, attempts to achieve effective desegregation (or "integration") by means of busing in some areas led to more families' moving out of former areas.

More generally, some historians suggest that white flight occurred in

response to population pressures, both from the large migration of

blacks from the rural Southern United States to urban cities of the Northern United States and the Western United States in the Great Migration and the waves of new immigrants from around the world.

However, some historians have challenged the phrase "white flight" as a

misnomer whose use should be reconsidered. In her study of West Side in Chicago during the post-war

era, historian Amanda Seligman argues that the phrase misleadingly

suggests that whites immediately departed when blacks moved into the

neighborhood, when in fact, many whites defended their space with

violence, intimidation, or legal tactics. Leah Boustan, Professor of Economics at Princeton, attributes white flight both to racism and economic reasons.

The business practices of redlining, mortgage discrimination, and racially restrictive covenants

contributed to the overcrowding and physical deterioration of areas

with large minority populations. Such conditions are considered to have

contributed to the emigration of other populations. The limited

facilities for banking and insurance, due to a perceived lack of

profitability, and other social services, and extra fees meant to hedge

against perceived profit issues, increased their cost to residents in

predominantly non-white suburbs and city neighborhoods. According to the environmental geographer Laura Pulido, the historical

processes of suburbanization and urban decentralization contribute to

contemporary environmental racism.

History

In 1870, The Nation covered the large-scale migrations of white Americans;

"The report of the Emigration Commissioners of Louisiana, for the past

year, estimates the white exodus from the Southern Atlantic States,

Alabama, and Mississippi, to the trans-Mississippi regions, at scores of

thousands". By 1888, with rhetoric typical of the time, Walter Thomas Mills's The Statesman publication predicted:

Social and political equality and the political supremacy

of the negro element in any southern state must lead to one of three

things: A white exodus, a war of races, or the destruction of representative institutions, as in the District of Columbia.

An 1894 biography of William Lloyd Garrison reveals the abolitionist's perception of the pre-Civil War

tension and how "the shadows of the impending civil disruption, had

brought about a white exodus" of Northerners to Southern states such as

Georgia.

In the years leading up to World War I, the newspapers in the Union of South Africa were reporting on the "spectre of white flight", in particular due to Afrikaners travelling to the Port of Durban in search of ships for Britain and Australia.

Academic research

In 1958, political scientist Morton Grodzins

identified that "once the proportion of non-whites exceeds the limits

of the neighborhood’s tolerance for interracial living, whites move

out." Grodzins termed this phenomenon the tipping point in the study of white flight.

In 2004, a study of UK census figures at the London School of Economics demonstrated evidence of white flight, resulting in ethnic minorities in inner-city areas becoming increasingly isolated from the ethnic White British population. The study, which examined the white population in London, the West Midlands, West Yorkshire, and Greater Manchester

between 1991 and 2001, also concluded that white population losses were

largest in areas with the highest ethnic minority populations.

In 2018, research at Indiana University showed that between 2000 and 2010 in the US, of a sample size of 27,891 Census tracts, 3,252 experienced "white flight". The examined areas had "an average magnitude loss of 40 percent of the original white population." Published in Social Science Research,

the study found "relative to poorer neighborhoods, white flight becomes

systematically more likely in middle-class neighborhoods at higher

thresholds of black, Hispanic, and Asian population presence."

Checkerboard and tipping models

In studies in the 1980s and 1990s, blacks said they were willing to

live in neighborhoods with 50/50 ethnic composition. Whites were also

willing to live in integrated neighborhoods, but preferred proportions

of more whites. Despite this willingness to live in integrated

neighborhoods, the majority still live in largely segregated

neighborhoods, which have continued to form.

In 1969, Nobel Prize-winning economist Thomas Schelling

published "Models of Segregation", a paper in which he demonstrated

through a "checkerboard model" and mathematical analysis, that even when

every agent prefers to live in a mixed-race neighborhood, almost

complete segregation of neighborhoods emerges as individual decisions

accumulate. In his "tipping model", he showed that members of an ethnic

group do not move out of a neighborhood as long as the proportion of

other ethnic groups is relatively low, but if a critical level of other

ethnicities is exceeded, the original residents may make rapid decisions

and take action to leave. This tipping point is viewed as simply the

end-result of a domino effect

originating when the threshold of the majority ethnicity members with

the highest sensitivity to sameness is exceeded. If these people leave

and are either not replaced or replaced by other ethnicities, then this

in turn raises the level of mixing of neighbors, exceeding the departure

threshold for additional people.

Africa

South Africa

About 800,000 out of an earlier total population of 5.2 million whites left post-apartheid South Africa after 1995, according to a 2009 report in Newsweek. The country has suffered a high rate of violent crime, a primary stated reason for emigration. Other causes cited in the Newsweek report include attacks against white farmers, concern about being excluded by affirmative action programmes, political instability and worries about corruption. Many of those who leave are highly educated, resulting in skills shortages.

Some observers fear the long-term consequences, as South Africa's labor

policies make it difficult to attract skilled immigrants. In the global

economy, some professionals and skilled people have been attracted to

work in the U.S. and European nations.

Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia)

Until 1980, the unrecognised Republic of Rhodesia held a well-publicised image as being one of two nations in sub-Saharan Africa

where a white minority of European descent and culture held political,

economic, and social control over a preponderantly black African

majority. Nevertheless, unlike white South Africans, a significant percentage of white Rhodesians represented recent immigrants from Europe. After World War II, there was a substantial influx of Europeans migrating into the region (formerly known as Southern Rhodesia), including former residents of India, Pakistan, and other parts of Africa. Also represented were working-class emigrants responding to economic opportunities. In 1969, only 41% of Rhodesia's white community were natural-born citizens, or 93,600 people. The remainder were naturalised European and South African citizens or expatriates, with many holding dual citizenship.

During the Rhodesian Bush War,

almost the entire white male population between eighteen and

fifty-eight was affected by various military commitments, and

individuals spent up to five or six months of the year on combat duty

away from their normal occupations in the civil service, commerce,

industry, or agriculture.

These long periods of service in the field led to an increased

emigration of men of military age. In November 1963, state media cited

the chief reasons for emigration as uncertainty about the future,

economic decline due to embargo and war, and the heavy commitments of

national service, which was described as "the overriding factor causing

people to leave".

Of the male emigrants in 1976 about half fell into the 15 to 39 age

bracket. Between 1960 and 1976 160,182 whites immigrated, while 157,724

departed. This dynamic turnover rate led to depressions in the property

market, a slump in the construction industry, and a decline in retail

sales.

The number of white Rhodesians peaked in 1975 at 278,000, and rapidly

declined as the bush war intensified. In 1976, around 14,000 whites left

the country, marking the first year since Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence in 1965 that more whites had left the country than arrived, with most leaving for South Africa. This became known as the 'chicken run', the earliest use of which was recorded the following year, often by Rhodesians who remained to contemptuously describe those who had left. Other phrases such as 'taking the gap' or 'gapping it' were also used.

As the outward flow increased, the phrase 'owl run' also came into use,

as leaving the country was deemed by many to be a wise choice. Disfavour with the biracial Zimbabwe Rhodesia administration in 1979 also contributed to a mass exodus.

The establishment of the Republic of Zimbabwe in 1980 sounded the death knell for white political power, and ushered in a new era of black majority rule.

White emigration peaked between 1980 and 1982 at 53,000 persons, with

the breakdown of law and order, an increase in crime in the rural areas,

and the provocative attitude of Zimbabwean officials being cited as the

main causes. Political conditions typically had a greater impact on the decision to migrate among white than black professionals. Between 1982 and 2000 Zimbabwe registered a net loss of 100,000 whites, or an average of 5,000 departures per year. A second wave of white emigration was sparked by President Robert Mugabe's violent land reform programme after 2000. Popular destinations included South Africa and Australia, which emigrants perceived to be geographically, culturally, or sociopolitically similar to their home country.

From a strictly economic point of view, the departure figures

were not as significant as the loss of the skills of those leaving.

A disproportionate number of white Zimbabwean emigrants were well

educated and highly skilled. Among those living in the United States,

for example, 53.7% had a bachelor's degree, while only 2% had not

completed secondary school. Most (52.4%) had occupied technical or supervisory positions of critical importance to the modern sector of the economy.

Inasmuch as black workers did not begin making large inroads into

apprenticeships and other training programs until the 1970s, few were in

a position to replace their white colleagues in the 1980s.

Europe

Denmark

A study of school choice in Copenhagen found that an immigrant

proportion of below 35% in the local schools did not affect parental

choice of schools. If the percentage of immigrant children rose above

this level, white Danes are far more likely to choose other schools.

Immigrants who speak Danish at home also opt out. Other immigrants, often more recent ones, stay with local schools.

Finland

In Finland, white flight has been observed in districts where the share of non-Finnish population is 20% or above. In Greater Helsinki region, there are more than 30 such districts. Those include e.g. Kallahti in Helsinki, Suvela in Espoo, and Länsimäki in Vantaa. Outside the Greater Helsinki region, the phenomenon has been witnessed at least in Varissuo district of Turku.

Ireland

A 2007 government report stated that immigration in Dublin

has caused "dramatic" white flight from elementary schools in a studied

area (Dublin 15). 27% of residents were foreign-born immigrants. The

report stated that Dublin was risking creating immigrant-dominated banlieues,

on the outskirts of a city, similar to such areas in France. The

immigrants in the area included Eastern Europeans (such as those from Poland), Asians, and Africans (mainly from Nigeria).

Norway

White flight in Norway has increased since the 1970s, with the immigration of non-Scandinavians from (in numerical order, starting with the largest): Poland, Pakistan, Iraq, Somalia, Vietnam, Iran, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, the former Yugoslavia, Thailand, Afghanistan, and Lithuania. By June 2009, more than 40% of Oslo schools had an immigrant majority, with some schools having a 97% immigrant share. Schools in Oslo are increasingly divided by ethnicity. For instance, in the Groruddalen

(Grorud valley), four boroughs which currently have a population of

around 165,000 saw the ethnic Norwegian population decrease by 1,500 in

2008, while the immigrant population increased by 1,600. In thirteen years, a total of 18,000 ethnic Norwegians have moved from the borough.

In January 2010, a news feature from Dagsrevyen on the public Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation said, "Oslo has become a racially divided city. In some city districts the racial segregation

starts already in kindergarten." Reporters said, "In the last years the

brown schools have become browner, and the white schools whiter," a

statement which caused a minor controversy.

Sweden

After the Second World War, immigration into Sweden occurred in three phases. The first was a direct result of the war, with refugees from concentration camps

and surrounding countries in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. The

second, prior to 1970, involved immigrant workers, mainly from Finland, Italy, Greece, and Yugoslavia. In the most recent phase, from the 1970s onwards, refugees immigrated from the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, joined later by their relatives.

A study which mapped patterns of segregation and congregation of incoming population groups

found that, if a majority group is reluctant to accept a minority

influx, they may leave the district, avoid the district, or use tactics

to keep the minority out. The minority group in turn react by either

dispersing or congregating, avoiding certain districts in turn. Detailed

analysis of data from the 1990s onwards indicates that the

concentration of immigrants in certain city districts, such as Husby in Stockholm and Rosengård in Malmö, is in part due to an immigration influx, but primarily caused by white flight.

According to researcher Emma Neuman at Linnaeus University,

the white flight phenomenon commences when the fraction of non-European

immigrants reaches 3-4%, but European immigration shows no such effect. High income earners and the highly educated move out first, so the ethnic segregation also leads to class segregation.

In a study performed at Örebro University,

mothers of young children were interviewed to study attitudes on

Swedishness, multiculturalism and segregation. It concluded that while

many expressed values such as ethnic diversity being an enriching

factor, when, in practice, it came to choosing schools or choosing which

district to move to, ensuring the children had access to a school with a

robust Swedish majority was also a consideration. This was because they

did not want their children to grow up in a school where they were a

minority, and wanted them to be in a good environment for learning the

Swedish language.

United Kingdom

For centuries, London

was the destination for refugees and immigrants from continental

Europe. Although all the immigrants were European, neighborhoods showed ethnic succession

over time, as older residents moved out and new immigrants moved in, an

early case of white flight (though the majority of London's population

was still ethnic British).

In the 2001 census, the London boroughs of Newham and Brent were found to be the first areas to have non-white majorities. The 2011 census

found that, for the first time, less than 50% of London's population

were white British, and that in some areas of London white British

people make up less than 20% of the population. A 2005 report stated

that white migration within the UK is mainly from areas with a high

ethnic minority population to those with predominantly white

populations; white British families have moved out of London, as many

immigrants have settled in the capital. The report's writers expressed

concern about British social cohesion, and stated that different ethnic

groups were living "parallel lives"; they were concerned that lack of

contact between the groups could result in fear more readily exploited

by extremists. In a study, the London School of Economics found similar results. A 2016 BBC documentary, Last Whites of the East End, covered the migration of whites from Newham to Essex. A 2019 Guardian article stated that "came to represent 'white flight' in the UK", and a 2013 Prospect magazine article gave Essex as an example of white flight.

Researcher Ludi Simpson has stated that the growth of ethnic

minorities in Britain is due mostly to natural population growth (births

outnumbering deaths), rather than immigration. Both white and non-white

Britons who can do so economically are equally likely to leave

mixed-race inner-city areas. In his opinion, these trends indicate counter urbanisation, rather than white flight.

North America

Canada

Toronto

In 2013, the Toronto Star examined the "identity crisis" of Brampton (a suburban city in the Greater Toronto Area), and referring to white Canadians,

the "loss of more than 23,000 people, or 12 per cent, in a decade when

the city’s population rose by 60 per cent". The paper reported University of Manitoba

sociologist Jason Edgerton's analysis that "After you control for

retirement, low birth rate, etc. some of the other (shrinkage) could be

white flight — former mainstream communities not comfortable being the

minority."

A 2016 article from The Globe and Mail,

addressing the diversity of Brampton, acknowledged that while academics

in Canada are sometimes reluctant to use the term of white flight, it

reported that:

[...] the Brampton story reveals that we have our own

version of white flight, and before we figure out how to manage

hyper-diverse and increasingly polarized cities like Greater Toronto, we

need to reflect on our own attitudes about race and ethnic diversity.

In 2018, The Guardian

covered the white flight that had occurred in Brampton, and how the

suburban city had been nicknamed "Bramladesh" and "Browntown", due to

its "73% visible minority, with its largest ethnic group Indian". It was also reported how "the white population fell from 192,400 in 2001 to 169,230 in 2011, and now hovers around 151,000."

Vancouver

In 2014, the Vancouver Sun addressed the issue of white flight across Metropolitan Vancouver. Detailing the phenomenon of "unconscious segregation", the article points to large East Asian and South Asian enclaves within Greater Vancouver such as Burnaby, East Vancouver, Richmond, South Vancouver and Surrey. In contrast, other cities and neighbourhoods within the metropolitan region such as Tsawwassen, South Surrey, White Rock and Langley host equally large white enclaves.

United States

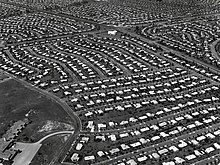

In the United States during the 1940s, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, low-cost mortgages through the G.I. Bill, and residential redlining enabled white families to abandon inner cities in favor of suburban living and prevent ethnic minorities from doing the same. The result was severe urban decay that, by the 1960s, resulted in crumbling "ghettos".

Prior to national data available in the 1950 US census, a migration

pattern of disproportionate numbers of whites moving from cities to

suburban communities was easily dismissed as merely anecdotal. Because

American urban populations were still substantially growing, a relative

decrease in one racial or ethnic component eluded scientific proof to

the satisfaction of policy makers. In essence, data on urban population

change had not been separated into what are now familiarly identified

its "components." The first data set potentially capable of proving

"white flight" was the 1950 census. But original processing of this

data, on older-style tabulation machines by the US Census Bureau, failed

to attain any approved level of statistical proof. It was rigorous

reprocessing of the same raw data on a UNIVAC I, led by Donald J. Bogue of the Scripps Foundation and Emerson Seim of the University of Chicago, that scientifically established the reality of white flight.

It was not simply a more powerful calculating instrument that

placed the reality of white flight beyond a high hurdle of proof

seemingly required for policy makers to consider taking action. Also

instrumental were new statistical methods developed by Emerson Seim for

disentangling deceptive counter-effects that had resulted when numerous

cities reacted to departures of a wealthier tax base by annexation. In

other words, central cities had been bringing back their new suburbs,

such that families that had departed from inner cities were not even

being counted as having moved from the cities.

During the later 20th century, industrial restructuring

led to major losses of jobs, leaving formerly middle-class working

populations suffering poverty, with some unable to move away and seek

employment elsewhere. Real estate prices often fall in areas of

economic erosion, allowing persons with lower income to establish homes

in such areas. Since the 1960s and changed immigration laws, the United

States has received immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America,

Asia, and Africa. Immigration has changed the demographics

of both cities and suburbs, and the US has become a largely suburban

nation, with the suburbs becoming more diverse. In addition, Latinos, the fastest growing minority group in the US, began to migrate away from traditional entry cities and to cities in the Southwest, such as Albuquerque, Phoenix and Tucson. In 2006, the increased number of Latinos had made whites a minority group in some western cities.

Catalysts

Legal exclusion

In the 1930s, states outside the South (where racial segregation was legal) practiced unofficial segregation via exclusionary covenants in title deeds and real estate neighborhood redlining – explicit, legally sanctioned racial discrimination

in real property ownership and lending practices. Blacks were

effectively barred from pursuing homeownership, even when they were able

to afford it. Suburban expansion was reserved for middle-class and working-class

white people, facilitated by their increased wages incurred by the war

effort and by subsequent federally guaranteed mortgages (VA, FHA, HOLC)

available only to whites to buy new houses, such as those created by the

Federal Housing Administration.

Roads

After World War II, aided by the construction of the Interstate Highway System, many white Americans began leaving industrial cities for new housing in suburbs.

The roads served to transport suburbanites to their city jobs,

facilitating the development of suburbs, and shifting the tax base away

from the city. This may have exacerbated urban decay.

In some cases, such as in the Southern United States, local governments

used highway road constructions to deliberately divide and isolate black neighborhoods from goods and services, often within industrial corridors. In Birmingham, Alabama,

the local government used the highway system to perpetuate the racial

residence-boundaries the city established with a 1926 racial zoning law.

Constructing interstate highways through majority-black neighborhoods

eventually reduced the populations to the poorest proportion of people

financially unable to leave their destroyed community.

Blockbusting

The real estate business practice of "blockbusting" was a for-profit

catalyst for white flight, and a means to control non-white migration.

By subterfuge, real estate agents would facilitate black people buying a

house in a white neighborhood, either by buying the house themselves,

or via a white proxy buyer, and then re-selling it to the black family.

The remaining white inhabitants (alarmed by real estate agents and the

local news media), fearing devalued residential property, would quickly sell, usually at a loss. The realtors profited from these en masse sales and the ability to resell to the incoming black families, through arbitrage

and the sales commissions from both groups. By such tactics, the racial

composition of a neighborhood population was often changed completely

in a few years.

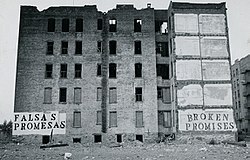

Association with urban decay

Urban

decay in the US: the South Bronx, New York City, was exemplar of the

federal and local government's abandonment of the cities in the 1970s

and 1980s; the Spanish sign reads "FALSAS PROMESAS", the English sign

reads "BROKEN PROMISES".

Urban decay is the sociological process whereby a city, or part of a

city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude. Its characteristics are depopulation, economic restructuring, abandoned buildings, high local unemployment (and thus poverty), fragmented families, political disenfranchisement,

crime, and a desolate, inhospitable city landscape. White flight

contributed to the draining of cities' tax bases when middle-class

people left. Abandoned properties attracted criminals and street gangs, contributing to crime.

In the 1970s and 1980s, urban decay was associated with Western

cities, especially in North America and parts of Europe. In that time,

major structural changes in global economies, transportation, and

government policy created the economic, then social, conditions

resulting in urban decay.

White flight in North America started to reverse in the 1990s, when the rich suburbanites returned to cities, gentrifying the decayed urban neighborhoods.

Government-aided white flight

New municipalities were established beyond the abandoned city's jurisdiction to avoid the legacy costs

of maintaining city infrastructures; instead new governments spent

taxes to establish suburban infrastructures. The federal government

contributed to white flight and the early decay of non-white city

neighborhoods by withholding maintenance capital mortgages, thus making

it difficult for the communities to either retain or attract

middle-class residents.

The new suburban communities limited the emigration of poor and non-white residents from the city by restrictive zoning;

thus, few lower-middle-class people could afford a house in the

suburbs. Many all-white suburbs were eventually annexed to the cities

their residents had left. For instance, Milwaukee, Wisconsin partially annexed towns such as Granville; the (then) mayor, Frank P. Zeidler, complained about the socially destructive "Iron Ring" of new municipalities incorporated in the post–World War II decade. Analogously, semi-rural communities, such as Oak Creek, South Milwaukee, and Franklin,

formally incorporated as discrete entities to escape urban annexation.

Wisconsin state law had allowed Milwaukee's annexation of such rural and

suburban regions that did not qualify for discrete incorporation per

the legal incorporation standards.

Desegregation of schools

In some areas, the post–World War II racial desegregation of the

public schools catalyzed white flight. In 1954, the US Supreme Court

case Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ordered the de jure termination of the "separate, but equal" legal racism established with the Plessy v. Ferguson

(1896) case in the 19th century. It declared that segregation of public

schools was unconstitutional. Many southern jurisdictions mounted massive resistance

to the policy. In some cases, white parents withdrew their children

from public schools and established private religious schools instead.

These schools, termed segregation academies,

sprung up in the American South between the late 1950s and mid-1970s

and allowed parents to prevent their children from being enrolled in

racially mixed schools.

Upon desegregation in 1957 in Baltimore, Maryland,

the Clifton Park Junior High School had 2,023 white students and 34

black students; ten years later, it had twelve white students and 2,037

black students. In northwest Baltimore, Garrison Junior High School's

student body declined from 2,504 whites and twelve blacks to 297 whites

and 1,263 blacks in that period.

At the same time, the city's working class population declined because

of the loss of industrial jobs as heavy industry restructured.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), the Supreme Court ordered the desegregation busing

of poor black students to suburban white schools, and suburban white

students to the city to try to integrate student populations. In Milliken v. Bradley (1974), the dissenting Justice William Douglas

observed, "The inner core of Detroit is now rather solidly black; and

the blacks, we know, in many instances are likely to be poorer."

Likewise, in 1977, the Federal decision in Penick v. The Columbus Board of Education (1977) accelerated white flight from Columbus, Ohio.

Although the racial desegregation of schools affected only public

school districts, the most vehement opponents of racial desegregation

have sometimes been whites whose children attended private schools.

A secondary, non-geographic consequence of school desegregation

and busing was "cultural" white flight: withdrawing white children from

the mixed-race public school system and sending them to private schools unaffected by US federal integration laws. In 1970, when the United States District Court for the Central District of California ordered the Pasadena Unified School District

desegregated, the proportion of white students (54%) reflected the

school district's proportion of whites (53%). Once the federally ordered

school desegregation began, whites who could afford private schools

withdrew their children from the racially diverse Pasadena

public school system. By 2004, Pasadena had 63 private schools

educating some 33% of schoolchildren, while white students made up only

16% of the public school populace. The Pasadena Unified School District

superintendent characterized public schools as "like the bogey-man" to

whites. He implemented policies to attract white parents to the racially

diverse Pasadena public school district.

Crime

Studies suggest that rising crime rates were one of the reasons that

white households left cities for suburbs in the 1960s and 1970s.

Samuel Kye (2018) cites several studies that identified "factors such

as crime and neighborhood deterioration, rather than racial prejudice,

as more robust determinants of white flight".

Ellen and O'Regan (2010) found that lower crime rates in city centers

are associated with less out-migration to suburbs, but they did not find

an effect on lower levels of crime attracting new households to the

city.

Oceania

Australia

In Sydney, Australian-born minority (white and non-white) people in Fairfield and Canterbury fell by three percentage points, six percentage points in Auburn, and three percentage points in Strathfield between 1991 and 1996. Only in Liverpool,

one of the more fast growth areas of Sydney, did both the

Australia-born and overseas-born male population increase over the

1991-1996 period. However, the rate of growth of the overseas-born was

far greater than that of the Australia-born, thus the sharp increase in

Liverpool's population share from 43.5 per cent to 49 per cent by 1996.

The Australia-born movers from the south-western suburbs relocated to Penrith in the northwest and Gosford and Wyong in the northeast.

According to the New South Wales Secondary Principals Council and the University of Western Sydney,

public schools in that state have experienced white flight to private

and Catholic schools wherever there is a large presence of Aboriginal and Middle Eastern students.

In 2018, NSW Labor Opposition leader Luke Foley talked about White flight, although he later apologised for the comments.

New Zealand

Percentages

of New Zealand school rolls occupied by certain ethnic groups in 2011,

broken down by socioeconomic decile. White flight is evident with

low-decile schools have a disproportionately low number of European

students and high numbers of Māori and Pasifika students, while the

inverse is true for high-decile schools.

White flight has been observed in low socioeconomic decile schools in New Zealand. Data from the Ministry of Education

found that 60,000 New Zealand European students attended low-decile

schools (situated in the poorest areas) in 2000, and had fallen to half

that number in 2010. The same data also found that high-decile schools

(which are in the wealthiest areas) had a corresponding increase in New

Zealand European students.

The Ministry claimed demographic changes were behind the shifts, but

teacher and principal associations have attributed white flight to

racial and class stigmas of low-decile schools, which commonly have

majority Maori and Pacific Islander rolls.

In one specific case, white flight has significantly affected Sunset Junior High School in a suburb of the city of Rotorua,

with the total number of students reduced from 700 to 70 in the early

1980s. All but one of the 70 students are Maori. The area has a

concentration of poor, low-skilled people, with struggling families, and

many single mothers. Related to the social problems of the families,

student educational achievement is low on the standard reading test.