Population figures for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization have been difficult to establish. By the end of the 20th century, most scholars gravitated toward an estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.

In an effort to circumvent the hold which the Ottoman Empire held on the overland trade routes to East Asia and the hold that the Aeterni regis granted to Portugal on maritime routes via the African coast and the Indian Ocean, the monarchs of the nascent Spanish Empire decided to fund Columbus' voyage in 1492, which eventually led to the establishment of settler-colonial states and the migration of millions of Europeans to the Americas. The population of African and European peoples in the Americas grew steadily, starting in 1492, and at the same time, the Indigenous population began to plummet. Eurasian diseases such as influenza, pneumonic plagues, and smallpox, in combination with conflict, forced removal, enslavement, imprisonment, and outright warfare with European newcomers reduced populations and disrupted traditional societies. The causes of the decline and the extent of it have been characterized as a genocide by some scholars.

Population overview

Pre-Columbian population figures are difficult to estimate due to the fragmentary nature of the evidence. Estimates range from 8–112 million. Scholars have varied widely on the estimated size of the Indigenous populations prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact. Estimates are made by extrapolations from small bits of data. In 1976, geographer William Denevan used the existing estimates to derive a "consensus count" of about 54 million people. Nonetheless, more recent estimates still range widely. In 1992, Denevan suggested that the total population was approximately 53.9 million and the populations by region were, approximately, 3.8 million for the United States and Canada, 17.2 million for Mexico, 5.6 million for Central America, 3 million for the Caribbean, 15.7 million for the Andes and 8.6 million for lowland South America. A 2020 genetic study suggests that prior estimates for the pre-Columbian Caribbean population may have been at least tenfold too large. Historian David Stannard estimates that the extermination of Indigenous peoples took the lives of 100 million people: "...the total extermination of many American Indian peoples and the near-extermination of others, in numbers that eventually totaled close to 100,000,000." A 2019 study estimates the pre-Columbian population Indigenous population contained more than 60 million people, but dropped to 6 million by 1600, based on a drop in atmospheric CO2 during that period. Other studies have disputed this conclusion.

The Indigenous population of the Americas in 1492 was not necessarily at a high point and may actually have already been in decline in some areas. Indigenous populations in most areas of the Americas reached a low point by the early 20th century.

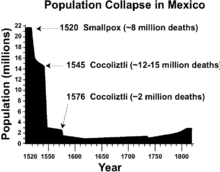

Using an estimate of approximately 37 million people in Mexico, Central and South America in 1492 (including 6 million in the Aztec Empire, 5–10 million in the Mayan States, 11 million in what is now Brazil, and 12 million in the Inca Empire), the lowest estimates give a death toll from all causes of 80% by the end of the 17th century (nine million people in 1650). Latin America would match its 15th-century population early in the 19th century; it numbered 17 million in 1800, 30 million in 1850, 61 million in 1900, 105 million in 1930, 218 million in 1960, 361 million in 1980, and 563 million in 2005. In the last three decades of the 16th century, the population of present-day Mexico dropped to about one million people. The Maya population is today estimated at six million, which is about the same as at the end of the 15th century, according to some estimates. In what is now Brazil, the Indigenous population declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated four million to some 300,000. Over 60 million Brazilians possess at least one Native South American ancestor, according to a DNA study.

While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Natives lived in North America before Columbus, estimates range from 3.8 million, as mentioned above, to 7 million people to a high of 18 million. Scholars vary on the estimated size of the Indigenous population in what is now Canada prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact. During the late 15th century is estimated to have been between 200,000 and two million, with a figure of 500,000 currently accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health. Although not without conflict, European Canadians' early interactions with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful. However repeated outbreaks of European infectious diseases such as influenza, measles and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity), combined with other effects of European contact, resulted in a twenty-five percent to eighty percent Indigenous population decrease post-contact. Roland G Robertson suggests that during the late 1630s, smallpox killed over half of the Wyandot (Huron), who controlled most of the early North American fur trade in the area of New France. In 1871 there was an enumeration of the Indigenous population within the limits of Canada at the time, showing a total of only 102,358 individuals. From 2006 to 2016, the Indigenous population has grown by 42.5 percent, four times the national rate. According to the 2011 Canadian Census, Indigenous peoples (First Nations – 851,560, Inuit – 59,445 and Métis – 451,795) numbered at 1,400,685, or 4.3% of the country's total population.

The population debate has often had ideological underpinnings. Low estimates were sometimes reflective of European notions of cultural and racial superiority. Historian Francis Jennings argued, "Scholarly wisdom long held that Indians were so inferior in mind and works that they could not possibly have created or sustained large populations." In 1998, Africanist Historian David Henige said many population estimates are the result of arbitrary formulas applied from unreliable sources.

Estimations

| Author | Date | USA and Canada | Mexico | Mesoamerica | Caribbean | Andes | Patagonia and Amazonia |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sapper | 1924 | 2 million-3 million | 12 million-15 million | 5 million-6 million | 3 million-4 million | 12 million-15 million | 3 million-5 million | 37 million-48.5 million |

| Kroeber | 1939 | 0.9 million | 3.2 million | 0.1 million | 0.2 million | 3 million | 1 million | 8.4 million |

| Steward | 1949 | 1 million | 4.5 million | 0.74 million | 0.22 million | 6.13 million | 2.9 million | 15.49 million |

| Rosenblat | 1954 | 1 million | 4.5 million | 0.8 million | 0.3 million | 4.75 million | 2.03 million | 13.38 million |

| Dobyns | 1966 | 9.8-12.25 million | 30-37.5 million | 10.8-13.5 million | 0.44-0.55 million | 30-37.5 million | 9-11.25 million | 90.04-112.55 million |

| Ubelaker | 1988 | 1.213-2.639 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Denevan | 1992 | 3.79 million | 17.174 million | 5.625 million | 3 million | 15.696 million | 8.619 million | 53.904 million |

| Snow | 2001 | 3.44 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Alchon | 2003 | 3.5 million | 16 million-18 million | 5 million-6 million | 2 million-3 million | 13 million-15 million | 7 million-8 million | 46.5 million-53.5 million |

| Thornton | 2005 | 7 million | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Estimations by tribe

Population size for Native American tribes is difficult to state definitively, but at least one writer has made estimates, often based on an assumed proportion of the number of warriors to total population for the tribe. Typical proportions were 5 people per one warrior and at least 1 up to 5 warriors (therefore at least 5-25 people) per lodge, cabin or house.

The total peak population size only for the tribes listed in this table is 3,210,215 in the US and Canada (including 327,600 in Canada).

Pre-Columbian Americas

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American land mass using DNA micro-satellite markers (genotype) sampled from North, Central, and South America have been analyzed against similar data available from other Indigenous populations worldwide. The Amerindian populations show a lower genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions. Decreasing genetic diversity with increasing geographic distance from the Bering Strait can be seen, as well as a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (genetic entry point). A higher level of diversity and lower level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America is observed. A relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations is a scenario that implies coastal routes were easier than inland routes for migrating peoples (Paleo-Indians) to traverse. The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70–250), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800–1,000 years. The data also show that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas. A new study in early 2018 suggests that the effective population size of the original founding population of Native Americans was about 250 people.

Depopulation by European diseases

Early explanations for the population decline of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas include the brutal practices of the Spanish conquistadores, as recorded by the Spaniards themselves, such as the encomienda system, which was ostensibly set up to protect people from warring tribes as well as to teach them the Spanish language and the Catholic religion, but in practice was tantamount to serfdom and slavery. The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos. The second European explanation was a perceived divine approval, in which God removed the natives as part of His "divine plan" to make way for a new Christian civilization. Many Native Americans viewed their troubles in a religious framework within their own belief systems.

According to later academics such as Noble David Cook, a community of scholars began "quietly accumulating piece by piece data on early epidemics in the Americas and their relation to the subjugation of native peoples." Scholars like Cook believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the natives had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans. One of the most devastating diseases was smallpox, but other deadly diseases included typhus, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, malaria, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and pertussis, which were chronic in Eurasia.

However, recently scholars have studied the link between physical colonial violence such as warfare, displacement, and enslavement, and the proliferation of disease among Native populations. For example, according to Coquille scholar Dina Gilio-Whitaker, "In recent decades, however, researchers challenge the idea that disease is solely responsible for the rapid Indigenous population decline. The research identifies other aspects of European contact that had profoundly negative impacts on Native peoples' ability to survive foreign invasion: war, massacres, enslavement, overwork, deportation, the loss of will to live or reproduce, malnutrition and starvation from the breakdown of trade networks, and the loss of subsistence food production due to land loss."

Further, Andrés Reséndez of the University of California, Davis points out that, even though the Spanish were aware of deadly diseases such as smallpox, there is no mention of them in the New World until 1519, implying that, until that date, epidemic disease played no significant part in the depopulation of the Antilles. The practices of forced labor, brutal punishment, and inadequate necessities of life, were the initial and major reasons for depopulation. Jason Hickel estimates that a third of Arawak workers died every six months from forced labor in these mines. In this way, "slavery has emerged as a major killer" of the indigenous populations of the Caribbean between 1492 and 1550, as it set the conditions for diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and malaria to flourish. Unlike the populations of Europe who rebounded following the Black Death, no such rebound occurred for the Indigenous populations.

Similarly, historian Jeffrey Ostler at the University of Oregon has argued that population collapses in North America throughout colonization were not mainly due to lack of Native immunity to European disease. Instead, he claims that "When severe epidemics did hit, it was often less because Native bodies lacked immunity than because European colonialism disrupted Native communities and damaged their resources, making them more vulnerable to pathogens." In specific regard to Spanish colonization of northern Florida and southeastern Georgia, Native peoples there "were subject to forced labor and, because of poor living conditions and malnutrition, succumbed to wave after wave of unidentifiable diseases." Further, in relation to British colonization in the Northeast, Algonquian speaking tribes in Virginia and Maryland "suffered from a variety of diseases, including malaria, typhus, and possibly smallpox." These diseases were not solely a case of Native susceptibility, however, because "as colonists took their resources, Native communities were subject to malnutrition, starvation, and social stress, all making people more vulnerable to pathogens. Repeated epidemics created additional trauma and population loss, which in turn disrupted the provision of healthcare." Such conditions would continue, alongside rampant disease in Native communities, throughout colonization, the formation of the United States, and multiple forced removals, as Ostler explains that many scholars "have yet to come to grips with how U.S. expansion created conditions that made Native communities acutely vulnerable to pathogens and how severely disease impacted them. ... Historians continue to ignore the catastrophic impact of disease and its relationship to U.S. policy and action even when it is right before their eyes."

Historian David Stannard says that by "focusing almost entirely on disease ... contemporary authors increasingly have created the impression that the eradication of those tens of millions of people was inadvertent—a sad, but both inevitable and "unintended consequence" of human migration and progress," and asserts that their destruction "was neither inadvertent nor inevitable," but the result of microbial pestilence and purposeful genocide working in tandem. He also wrote:

...Despite frequent undocumented assertions that disease was responsible for the great majority of indigenous deaths in the Americas, there does not exist a single scholarly work that even pretends to demonstrate this claim on the basis of solid evidence. And that is because there is no such evidence, anywhere. The supposed truism that more native people died from disease than from direct face-to-face killing or from gross mistreatment or other concomitant derivatives of that brutality such as starvation, exposure, exhaustion, or despair is nothing more than a scholarly article of faith...

In contrast, historian Russel Thornton has pointed out that there were disastrous epidemics and population losses during the first half of the sixteenth century “resulting from incidental contact, or even without direct contact, as disease spread from one American Indian tribe to another.” Thornton has also challenged higher Indigenous population estimates, which are based on the Malthusian assumption that “populations tend to increase to, and beyond, the limits of the food available to them at any particular level of technology."

The European colonization of the Americas resulted in the deaths of so many people it contributed to climatic change and temporary global cooling, according to scientists from University College London. A century after the arrival of Christopher Columbus, some 90% of Indigenous Americans had perished from "wave after wave of disease", along with mass slavery and war, in what researchers have described as the "great dying". According to one of the researchers, UCL Geography Professor Mark Maslin, the large death toll also boosted the economies of Europe: "the depopulation of the Americas may have inadvertently allowed the Europeans to dominate the world. It also allowed for the Industrial Revolution and for Europeans to continue that domination."

Biological warfare

When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the Indigenous populations in near ruins. No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American natives, and some efforts were made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their labor force (compelled to work under the encomienda system). The cattle introduced by the Spanish contaminated various water reserves which Native Americans dug in the fields to accumulate rainwater. In response, the Franciscans and Dominicans created public fountains and aqueducts to guarantee access to drinking water. But when the Franciscans lost their privileges in 1572, many of these fountains were no longer guarded and so deliberate well poisoning may have happened. Although no proof of such poisoning has been found, some historians believe the decrease of the population correlates with the end of religious orders' control of the water.

In the centuries that followed, accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common. Well-documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are very rare, but may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged. Many of the instances likely went unreported, and it is possible that documents relating to such acts were deliberately destroyed, or sanitized. By the middle of the 18th century, colonists had the knowledge and technology to attempt biological warfare with the smallpox virus. They well understood the concept of quarantine, and that contact with the sick could infect the healthy with smallpox, and those who survived the illness would not be infected again. Whether the threats were carried out, or how effective individual attempts were, is uncertain.

One such threat was delivered by fur trader James McDougall, who is quoted as saying to a gathering of local chiefs, "You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men. But this is for my enemies and not my friends." Likewise, another fur trader threatened Pawnee Indians that if they didn't agree to certain conditions, "he would let the smallpox out of a bottle and destroy them." The Reverend Isaac McCoy was quoted in his History of Baptist Indian Missions as saying that the white men had deliberately spread smallpox among the Indians of the southwest, including the Pawnee tribe, and the havoc it made was reported to General Clark and the Secretary of War. Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, "They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them." So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.

During the siege of British-held Fort Pitt in the Seven Years' War, Colonel Henry Bouquet ordered his men to take smallpox-infested blankets from their hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain's ledger, "To convey the Smallpox to the Indians". In the following weeks, Sir Jeffrey Amherst conspired with Bouquet to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans, writing, "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them." His Colonel agreed to try.

Most scholars have asserted that the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic was "started among the tribes of the upper Missouri River by failure to quarantine steamboats on the river", and Captain Pratt of the St. Peter "was guilty of contributing to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. The law calls his offense criminal negligence. Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences." However, some sources attribute the 1836–40 epidemic to the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans, with historian Ann F. Ramenofsky writing, "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets. In the nineteenth century, the U. S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans, especially Plains groups, to control the Indian problem." In Brazil, well into the 20th century, deliberate infection attacks continued as Brazilian settlers and miners transported infections intentionally to the native groups whose lands they coveted.

Vaccination

After Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that the smallpox vaccination worked, the technique became better known and smallpox became less deadly in the United States and elsewhere. Many colonists and natives were vaccinated, although, in some cases, officials tried to vaccinate natives only to discover that the disease was too widespread to stop. At other times, trade demands led to broken quarantines. In other cases, natives refused vaccination because of suspicion of whites. The first international healthcare expedition in history was the Balmis expedition which had the aim of vaccinating Indigenous peoples against smallpox all along the Spanish Empire in 1803. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Sioux at Sioux Agency. The Santee Sioux refused vaccination and many died.

Depopulation by European conquest

War and violence

While epidemic disease was a leading factor of the population decline of the American Indigenous peoples after 1492, there were other contributing factors, all of them related to European contact and colonization. One of these factors was warfare. According to demographer Russell Thornton, although many people died in wars over the centuries, and war sometimes contributed to the near extinction of certain tribes, warfare and death by other violent means was a comparatively minor cause of overall native population decline.

From the U.S. Bureau of the Census in 1894, wars between the government and the Indigenous peoples ranged over 40 in number over the previous 100 years. These wars cost the lives of approximately 19,000 white people, and the lives of about 30,000 Indians, including men, women, and children. They safely estimated that the amount of Native people who were killed or wounded was actually around fifty percent more than what was recorded.

There is some disagreement among scholars about how widespread warfare was in pre-Columbian America, but there is general agreement that war became deadlier after the arrival of the Europeans and their firearms. The South or Central American infrastructure allowed for thousands of European conquistadors and tens of thousands of their Indian auxiliaries to attack the dominant Indigenous civilization. Empires such as the Incas depended on a highly centralized administration for the distribution of resources. Disruption caused by the war and the colonization hampered the traditional economy, and possibly led to shortages of food and materials. Across the western hemisphere, war with various Native American civilizations constituted alliances based out of both necessity or economic prosperity and, resulted in mass-scale intertribal warfare. European colonization in the North American continent also contributed to a number of wars between Native Americans, who fought over which of them should have first access to new technology and weaponry—like in the Beaver Wars.

Exploitation

Some Spaniards objected to the encomienda system of labor, notably Bartolomé de las Casas, who insisted that the Indigenous people were humans with souls and rights. Due to many revolts and military encounters, Emperor Charles V helped relieve the strain on both the native laborers and the Spanish vanguards probing the Caribana for military and diplomatic purposes. Later on New Laws were promulgated in Spain in 1542 to protect isolated natives, but the abuses in the Americas were never entirely or permanently abolished. The Spanish also employed the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita, and treated their subjects as something between slaves and serfs. Serfs stayed to work the land; slaves were exported to the mines, where large numbers of them died. In other areas the Spaniards replaced the ruling Aztecs and Incas and divided the conquered lands among themselves ruling as the new feudal lords with often, but unsuccessful lobbying to the viceroys of the Spanish crown to pay Tlaxcalan war demnities. The infamous Bandeirantes from São Paulo, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Serfdom existed as such in parts of Latin America well into the 19th century, past independence. Historian Andrés Reséndez argues that even though the Spanish were aware of the spread of smallpox, they made no mention of it until 1519, a quarter century after Columbus arrived in Hispaniola. Instead he contends that enslavement in gold and silver mines was the primary reason why the Native American population of Hispaniola dropped so significantly. and that even though disease was a factor, the native population would have rebounded the same way Europeans did following the Black Death if it were not for the constant enslavement they were subject to. He further contends that enslavement of Native Americans was in fact the primary cause of their depopulation in Spanish territories; that the majority of Indians enslaved were women and children compared to the enslavement of Africans which mostly targeted adult males and in turn they were sold at a 50% to 60% higher price, and that 2,462,000 to 4,985,000 Amerindians were enslaved between Columbus's arrival and 1900.

Massacres

- The Pequot War in early New England.

- In mid-19th century Argentina, post-independence leaders Juan Manuel de Rosas and Julio Argentino Roca engaged in what they presented as a "Conquest of the Desert" against the natives of the Argentinian interior, leaving over 1,300 Indigenous dead.

- While some California tribes were settled on reservations, others were hunted down and massacred by 19th century American settlers. It is estimated that at least 9,400 to 16,000 California Indians were killed by non-Indians, mostly occurring in more than 370 massacres (defined as the "intentional killing of five or more disarmed combatants or largely unarmed noncombatants, including women, children, and prisoners, whether in the context of a battle or otherwise").

Displacement and disruption

Throughout history, Indigenous people have been subjected to the repeated and forced removal from their land. Beginning in the 1830s, there was the relocation of an estimated 100,000 Indigenous people in the United States called the “Trail of Tears". The tribes affected by this specific removal were the Five Civilized Tribes: The Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole. The treaty of New Echota, was enacted, which stated that the United States “would give Cherokee land west of the Mississippi in exchange for $5,000,000”. According to Jeffrey Ostler, "Of the 80,000 Native people who were forced west from 1830 into the 1850s, between 12,000 and 17,000 perished." Ostler states that "the large majority died of interrelated factors of starvation, exposure and disease".

In addition to the removal of the Southern Tribes, there were multiple other removals of Northern Tribes also known as "Trails of Tears." For example, "In the free labor states of the North, federal and state officials, supported by farmers, speculators and business interests, evicted Shawnees, Delawares, Senecas, Potawatomis, Miamis, Wyandots, Ho-Chunks, Ojibwes, Sauks and Meskwakis." These Nations were moved West of the Mississippi into what is now known as Eastern Kansas, and numbered 17,000 on arrival. According to Ostler, "by 1860, their numbers had been cut in half" due to low fertility, high infant mortality, and increased disease caused by conditions such as polluted drinking water, few resources, and social stress.

Ostler also writes that the areas that Northern tribes were removed to were already inhabited: "The areas west of the Mississippi River were home to other Indigenous nations— Osages, Kanzas, Omahas, Ioways, Otoes and Missourias. To make room for thousands of people from the East, the government dispossessed these nations of much their lands." Ostler writes that in 1840, when Northern Nations were moved onto their land, "The combined population of these western nations was 9,000 ... 20 years later, it had fallen to 6,000."

Later apologies by government officials

On 8 September 2000, the head of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally apologized for the agency's participation in the ethnic cleansing of Western tribes. In a speech before representatives of Native American peoples in June 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom apologized for the "California Genocide." Newsom said, "That’s what it was, a genocide. No other way to describe it. And that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books."