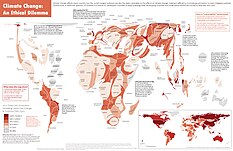

Climate justice is an approach to climate action that focuses on the unequal impacts of climate change on marginalized or otherwise vulnerable populations. Climate justice wants to achieve an equitable distribution of both the burdens of climate change and the efforts to mitigate climate change. Climate justice is a type of environmental justice.

Climate justice examines concepts such as equality, human rights, collective rights, and the historical responsibilities for climate change. This is done by relating the causes and effects of climate change to concepts of justice, particularly environmental justice and social justice. Presently and historically, marginalized communities often face the worst consequences of climate change. Depending on the country and context, this may include people with low-incomes, indigenous communities or communities of color. There is a growing consensus that people in regions that are the least responsible for climate change often tend to suffer the greatest consequences. They might also be further disadvantaged by responses to climate change which might exacerbate existing inequalities. This situation is known as the 'triple injustices' of climate change.

Conceptions of climate justice can be grouped along the lines of procedural justice and distributive justice. The former stresses fair, transparent and inclusive decision-making. The latter stresses a fair distribution of the costs and outcomes of climate change (substantive rights). There are at least ten different principles that are helpful to distribute climate costs fairly. Other approaches focus on addressing social implications of climate change mitigation. If these are not addressed properly, this could result in profound economic and social tensions. It could even lead to delays in necessary changes.

Climate justice actions can include the growing global body of climate litigation. In 2017, a report of the United Nations Environment Programme identified 894 ongoing legal actions worldwide.

Definition and objectives

Use and popularity of climate justice language has increased dramatically in recent years, yet climate justice is understood in many ways, and the different meanings are sometimes contested. At its simplest, conceptions of climate justice can be grouped along the following two lines:

- procedural justice, which emphasizes fair, transparent and inclusive decision making, and

- distributive justice, which places the emphasis on who bears the costs of both climate change and the actions taken to address it.

The objectives of climate justice can be described as: "to encompasses a set of rights and obligations, which corporations, individuals and governments have towards those vulnerable people who will be in a way significantly disproportionately affected by climate change."

Climate justice examines concepts such as equality, human rights, collective rights, and the historical responsibilities for climate change. Climate justice is mainly concerned with the procedural and distributive ethical dimensions of and for climate change mitigation.

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report underlines another principle of climate justice which is the "recognition which entails basic respect and robust engagement with and fair consideration of diverse cultures and perspectives". Alternatively, recognition and respect can be understood as the underlying basis for distributive and procedural justice.

Related fields are environmental justice and social justice.

Causes of injustice

Economic systems

Whether fundamental differences in economic systems, such as capitalism versus socialism, are the, or a, root cause of climate injustice is a contentious issue. In this context, fundamental disagreements arise between liberal and conservative environmental groups on one side and leftist and radical organizations on the other. While the former often tend to blame the excesses of neoliberalism for climate change and argue in favor of market-based reform within capitalism, the latter view capitalism with its exploitative traits as the underlying central issue. Other possible causal explanations include hierarchies based on the group differences and the nature of the fossil fuel regime itself.

Systemic causes

It has been argued that the unwarranted rate of climate change, along with its inequality of burdens, is a structural injustice. There is political responsibility for the maintenance and support of historically constituted structural processes. This is despite assumed viable potential alternative models based on novel technologies and means. As a criterion for determining responsibility for climate change, individual causal contribution or capacity does not matter as much as responsibility for the perpetuation of carbon-intensive structures, practices, and institutions. These structures constitute the global politico-economic system, rather than enabling structural changes towards a system that does not naturally facilitate unsustainable exploitation of people and nature.

For others, climate justice could be pursued through existing economic frameworks, global organizations and policy mechanisms. Therefore, the root-causes could be found in the causes that so far inhibited global implementation of measures like emissions trading schemes, specifically forms that deliver the assumed mitigation results.

Disproportionality between causality and burden

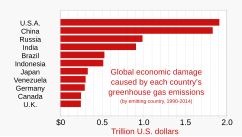

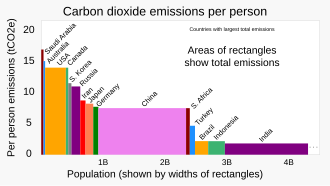

The responsibility for anthropogenic climate change differs substantially among individuals and groups. Many of the people and nations most affected by climate change are among the least responsible for it. The most affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts and robust action by them is necessary for prospects of moving towards safer environmental conditions.

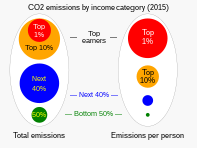

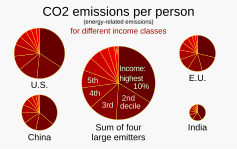

According to a 2020 report by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute, the richest 1% of the global population have caused twice as much carbon emissions as the poorest 50% over the 25 years from 1990 to 2015. This was, respectively, during that period, 15% of cumulative emissions compared to 7%. A second 2023 report found the richest 1% of humans produce more carbon emissions than poorest 66%, while the top 10% richest people account for more than half of global carbon emissions. half of the population is directly responsible for less than 20% of energy footprints and consume less than the top 5% in terms of trade-corrected energy. High-income individuals usually have higher energy footprints as they disproportionally use their larger financial resources for energy-intensive goods. In particular, the largest disproportionality was identified to be in the domain of transport, where the top 10% consume 56% of vehicle fuel and conduct 70% of vehicle purchases.

A 2023 review article found that if there were a 2oC temperature rise by 2100, roughly 1 billion primarily poor people would die as a result of primarily wealthy people's greenhouse gas emissions.

Intergenerational equity

The nations and the world population need to make changes, including sacrifices (like uncomfortable lifestyle-changes, alterations to public spending and changes to choice of work), today to enable climate justice for future generations.

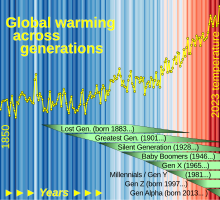

Preventable severe effects of climate change are likely to occur during the lifetime of the present adult population. Under current climate policy pledges, children born in 2020 (e.g. "Generation Alpha") will experience over their lifetimes, 2–7 times as many heat waves, as well as more of other extreme weather events compared to people born in 1960. This, along with other projections, raises issues of intergenerational equity as it was these generations (specific groups and individuals and their collective governance and perpetuated economics) who are mainly responsible for the burden of climate change.

This illustrates that emissions produced by any given generation can lock-in damage for one or more future generations, making climate change progressively more threatening for the generations affected than for the generation responsible for the threats. The climate system contains tipping points, such as the amount of deforestation of the Amazon that will launch the forest's irreversible decline. A generation whose continued emissions drive the climate system past such significant tipping points inflicts severe injustice on multiple future generations.

Disproportionate impacts on disadvantaged groups

Disadvantaged groups will continue to be disproportionately impacted as climate change persists. These groups will be affected due to inequalities based on demographic characteristics such as differences in gender, race, ethnicity, age, and income. Inequality increases the exposure of disadvantaged groups to harmful effects of climate change while also increasing their susceptibility to destruction caused by climate change. The damage is worsened because disadvantaged groups are last to receive emergency relief and are rarely included in the planning process at local, national and international levels for coping with the impacts of climate change.

Communities of color, women, indigenous groups, and people of low-income all face higher vulnerability to climate change. These groups will be disproportionately impacted by heat waves, air quality, and extreme weather events. Women are also disadvantaged and will be affected by climate change differently than men. This may impact the ability of minority groups to adapt, unless steps are taken to provide these groups with more access to universal resources. Indigenous groups are affected by the consequences of climate change even though they historically have contributed the least to causing it. Indigenous peoples are unjustifiably impacted due to their low income, and continue to have fewer resources to cope with climate change.

Responses to improve climate justice

One generation must not be allowed to consume large portions of the CO2 budget while bearing a relatively minor share of the reduction effort if this would involve leaving subsequent generations with a drastic reduction burden and expose their lives to comprehensive losses of freedom.

— German Federal Constitutional Court

April 2021

The rights of nature protect ecosystems and natural processes for their intrinsic value, thus complementing them with the human right to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment. The rights of nature, like all constitutional rights, are justiciable and, consequently, judges are obliged to guarantee them.

— Constitutional Court of Ecuador

10 November 2021

Common principles of justice in burden-sharing

There are three common principles of justice in burden-sharing that can be used in making decisions on who bears the larger burdens of climate change globally and domestically: a) those who most caused the problem, b) those who have the most burden-carrying ability and c) those who have benefited most from the activities that cause climate change. Observing calls for climate reparations in scientific literature, among climate movements and in policy debates, a 2023 study estimated that the top 21 fossil fuel companies would owe cumulative climate reparations of $5.4 trillion over the period 2025–2050.

Another method of deciding-making starts from the objective of preventing climate change e.g. beyond 1.5 °C, and from there reasons backwards to who should do what. This makes use of the principles of justice in burden-sharing to maintain fairness.

Court cases and litigation

By December 2022, the number of climate change-related lawsuits had grown to 2,180, more than half in the U.S. (1,522 lawsuits). Based on existing laws, some relevant parties can already be forced into action (to the degree of accountability, monitoring and law enforcement capacities and assessments of feasibility) by means of courts.

Human rights

... acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity, ...

— The Glasgow climate pact

13 November 2021

Challenges

Societal disruption and policy support

Climate justice may often conflict with social stability. For example, interventions that establish more just product pricing could result in social unrest. Socioeconomic decarbonization interventions could lead to decreased material possessions, number of freely choosable options, comfort, maintained habits and salaries, and also temporary increased unemployment rates. This may be problematic with current socioeconomic structures.

However, multiple studies estimate that if a rapid transition were to be implemented in certain ways the number of full-time jobs formally recognized in the economy could increase overall at least temporarily due to increased demand for labor to e.g. build public infrastructure and other green jobs to build the renewable energy system.

The urgent need for and extent of policies, especially when seeking to facilitate lifestyle-changes and shifts on an industry scale, could lead to social tension and decrease levels of public support for political parties in power. For instance, keeping gas prices low is often "really good for the poor and the middle class".

Loss and damage discussions

Some may see climate justice arguments for compensation by rich countries for disasters and similar problems in developing countries (as well as for domestic disasters) as a way for "limitless liability" by which at least high levels of compensations could drain a society's resources, efforts, focus and financial funds away from efficient preventive climate change mitigation towards e.g. immediate climate change relief compensations or climate-unrelated expenses of the receiving country or people.

Fossil-fuels dependent states

Fossil fuel phase out is projected to affect states and their citizens with large or central industries of fossil-fuels extraction – including OPEC states – differently than other nations. These states have obstructed climate negotiations and it has been argued that, due to their wealth, they should not need to receive financial support from other countries but could implement adequate transitions on their own in terms of financial resources.

A study suggested governments of nations that have historically benefited from extraction should take the lead, with countries that have a high dependency on fossil fuels but low capacity for transition needing some support to follow. In particular, transitional impacts of a rapid extraction phase out is thought to be better absorbed in diversified, wealthier economies that should bear discrepancies in costs needed for a "just transition" as they are most able to bear it and may have better capacities for enacting absorptive socioeconomic policies.

Conflicting interest-driven interpretations as barriers to agreements

Different interpretations and perspectives, arising from different interests, needs, circumstances, expectations, considerations and histories, can lead to highly varying ideas of what is "fair". This may make it more difficult for countries to reach an agreement, similar to the prisoner's dilemma. Developing effective, legitimate and enforceable agreements could thereby be substantially complicated, especially if traditional methods or tools of policy-making are used, in-sum trusted third party expert authorities are absent and the scientific research base relevant for the decision-making – such as studies and data about the problem, potential mitigation measures and capacities – is not robust. Fundamental fairness principles could include:

- Responsibility

- Capability and

- Rights (needs)

for which country characteristics can predict relative support. The shared problem-characteristics of climate change could incentivize developing countries to act in concert to deter developed countries from "passing their climate costs onto them" and thereby improve the global mitigation effectiveness to 1.5 °C.

History

Developed countries, as the main cause of climate change, in assuming their historical responsibility, must recognize and honor their climate debt in all of its dimensions as the basis for a just, effective, and scientific solution to climate change. (...) The focus must not be only on financial compensation, but also on restorative justice, understood as the restitution of integrity to our Mother Earth and all its beings.

World People's Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, People's Agreement, April 2010, Cochabamba, Bolivia

The concept of climate justice was deeply influential on climate negotiations years before the term "climate justice" was regularly applied to the concept. In December 1990 the United Nations appointed an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to draft what became the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC), adopted at the UN Conference on the Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. As the name "Environment and Development" indicated, the fundamental goal was to coordinate action on climate change with action on sustainable development. It was impossible to draft the text of the FCCC without confronting central questions of climate justice concerning how to share the responsibilities of slowing climate change fairly between developed nations and developing nations.

The issue of the fair terms for sharing responsibility was raised forcefully for the INC by statements about climate justice from developing countries. In response, the FCCC adopted the now-famous (and still-contentious) principles of climate justice embodied in Article 3.1: "The Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof." The first principle of climate justice embedded in Article 3.1 is that calculations of benefits (and burdens) must include not only those for the present generation but also those for future generations. The second is that responsibilities are "common but differentiated", that is, every country has some responsibilities, but equitable responsibilities are different for different types of countries. The third is that a crucial instance of different responsibilities is that in fairness developed countries' responsibilities must be greater. How much greater continues to be debated politically.

In 2000, at the same time as the Sixth Conference of the Parties (COP 6), the first Climate Justice Summit took place in The Hague. This summit aimed to "affirm that climate change is a rights issue" and to "build alliances across states and borders" against climate change and in favor of sustainable development.

Subsequently, in August–September 2002, international environmental groups met in Johannesburg for the Earth Summit. At this summit, also known as Rio+10, as it took place ten years after the 1992 Earth Summit, the Bali Principles of Climate Justice were adopted.

Climate Justice affirms the rights of communities dependent on natural resources for their livelihood and cultures to own and manage the same in a sustainable manner, and is opposed to the commodification of nature and its resources.

Bali Principles of Climate Justice, article 18, August 29, 2002

In 2004, the Durban Group for Climate Justice was formed at an international meeting in Durban, South Africa. Here representatives from NGOs and peoples' movements discussed realistic policies for addressing climate change.

In 2007 at the 13th Conference of the Parties (COP 13) in Bali, the global coalition Climate Justice Now! was founded, and, in 2008, the Global Humanitarian Forum focused on climate justice at its inaugural meeting in Geneva.

In 2009, the Climate Justice Action Network was formed during the run-up to the Copenhagen Summit. It proposed civil disobedience and direct action during the summit, and many climate activists used the slogan 'system change not climate change'.

In April 2010, the World People's Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth took place in Tiquipaya, Bolivia. It was hosted by the government of Bolivia as a global gathering of civil society and governments. The conference published a "People's Agreement" calling, among other things, for greater climate justice.

In September 2013 the Climate Justice Dialogue convened by the Mary Robinson Foundation and the World Resources Institute released their Declaration on Climate Justice in an appeal to those drafting the proposed agreement to be negotiated at COP-21 in Paris in 2015.

In December 2018, the People's Demands for Climate Justice, signed by 292,000 individuals and 366 organizations, called upon government delegates at COP24 to comply with a list of six climate justice demands. One of the demands was to "Ensure developed countries honor their "Fair Shares" for largely fueling this crisis."

Some advance was achieved at the Paris climate finance summit at June 2023. The World Bank allowed to low income countries temporarily stop paying debts if they are hit by climate disaster. Most of financial help to climate vulnerable countries is coming in the form of debts, what often worsens the situation as those countries are overburdened with debts. Around 300 billion dollars was pledged as financial help in the next years, but trillions are needed to really solve the problem. More than 100 leading economists signed a letter calling for an extreme wealth tax as a solution (2% tax can generate around 2.5 trillion). It can serve as a loss and damage mechanism as the 1% of richest people is responsible for twice as many emissions as the poorest 50%.

Examples

Subsistence farmers in Latin America

Several studies that investigated the impacts of climate change on agriculture in Latin America suggest that in the poorer countries of Latin America, agriculture composes the most important economic sector and the primary form of sustenance for small farmers. Maize is the only grain still produced as a sustenance crop on small farms in Latin American nations. The projected decrease of this grain and other crops can threaten the welfare and the economic development of subsistence communities in Latin America. Food security is of particular concern to rural areas that have weak or non-existent food markets to rely on in the case food shortages. In August 2019, Honduras declared a state of emergency when a drought caused the southern part of the country to lose 72% of its corn and 75% of its beans. Food security issues are expected to worsen across Central America due to climate change. It is predicted that by 2070, corn yields in Central America may fall by 10%, beans by 29%, and rice by 14%. With Central American crop consumption dominated by corn (70%), beans (25%), and rice (6%), the expected drop in staple crop yields could have devastating consequences.

The expected impacts of climate change on subsistence farmers in Latin America and other developing regions are unjust for two reasons. First, subsistence farmers in developing countries, including those in Latin America are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change Second, these nations were the least responsible for causing the problem of anthropogenic induced climate.

Disproportionate vulnerability to climate disasters is socially determined. For example, socioeconomic and policy trends affecting smallholder and subsistence farmers limit their capacity to adapt to change. A history of policies and economic dynamics has negatively impacted rural farmers. During the 1950s and through the 1980s, high inflation and appreciated real exchange rates reduced the value of agricultural exports. As a result, farmers in Latin America received lower prices for their products compared to world market prices. Following these outcomes, Latin American policies and national crop programs aimed to stimulate agricultural intensification. These national crop programs benefitted larger commercial farmers more. In the 1980s and 1990s low world market prices for cereals and livestock resulted in decreased agricultural growth and increased rural poverty.

Perceived vulnerability to climate change differs even within communities, as in the example of subsistence farmers in Calakmul, Mexico.

Adaptive planning is challenged by the difficulty of predicting local scale climate change impacts. A crucial component to adaptation should include government efforts to lessen the effects of food shortages and famines. Planning for equitable adaptation and agricultural sustainability will require the engagement of farmers in decision-making processes.

Hurricane Katrina