Microplastics are small barely visible pieces of plastic that enter and pollute the environment. To clarify, microplastics are not a specific kind of plastic, but rather is any type of plastic fragment that is less than five millimeters in length according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA classifies microplastics as less than 5 mm in diameter. They enter natural ecosystems from a variety of sources, including, but not limited to, cosmetics, clothing, and industrial processes.

Two classifications of microplastics currently exist. Primary microplastics, any plastic fragment or particle that is already less than 5.0 mm in size or less before entering the environment. These include microfibers from clothing, microbeads, and plastic pellets (also known as nurdles). Secondary microplastics, microplastics that are created from the degradation of larger plastic products once they enter the environment through natural weathering processes. Such sources of secondary microplastics include water and soda bottles, fishing nets, and plastic bags. Both types are recognized to persist in the environment at high levels, particularly in aquatic and marine ecosystems.

Two classifications of microplastics currently exist. Primary microplastics, any plastic fragment or particle that is already less than 5.0 mm in size or less before entering the environment. These include microfibers from clothing, microbeads, and plastic pellets (also known as nurdles). Secondary microplastics, microplastics that are created from the degradation of larger plastic products once they enter the environment through natural weathering processes. Such sources of secondary microplastics include water and soda bottles, fishing nets, and plastic bags. Both types are recognized to persist in the environment at high levels, particularly in aquatic and marine ecosystems.

Image of microplastic samples in a lab

Additionally, plastics degrade slowly, often over hundreds if not thousands of years. This increases the probability of microplastics being ingested and incorporated into, and accumulated in, the bodies and tissues of many organisms. The entire cycle and movement of microplastics in the environment is not yet known, but research is currently underway to investigate this issue.

Polyethylene based microspherules in toothpaste

Worsening matters, microplastics are common in our world today. In 2014, it was estimated that there are between fifteen and fifty-one trillion individual pieces of microplastic in the world’s oceans, which was estimated to weigh between 93,000 and 236,000 tons.

Microplastic fibers identified in the marine environment

Microplastics in sediments from rivers

a)

Artificial turf football field with ground tyre rubber (GTR) used for

cushioning. b) Microplastics from the same field, washed away by rain,

found in nature close to a stream.

Classification

Primary microplastics

These are small pieces of plastic that are purposefully manufactured. They are usually used in facial cleansers and cosmetics, or in air blasting technology. In some cases, their use in medicine as vectors for drugs was reported. Microplastic "scrubbers", used in exfoliating hand cleansers and facial scrubs, have replaced traditionally used natural ingredients, including ground almonds, oatmeal and pumice. Primary microplastics have also been produced for use in air blasting technology. This process involves blasting acrylic, melamine or polyester microplastic scrubbers at machinery, engines and boat hulls to remove rust and paint. As these scrubbers are used repeatedly until they diminish in size and their cutting power is lost, they often become contaminated with heavy metals such as cadmium, chromium, and lead. Although many companies have committed to reducing the production of microbeads there are still many bioplastic microbeads that also have a long degradation life cycle similar to normal plastic.Secondary microplastics

These are small pieces of plastic derived from the breakdown of larger plastic debris, both at sea and on land. Over time, a culmination of physical, biological and chemical processes, including photo degradation caused by sunlight exposure, can reduce the structural integrity of plastic debris to a size that is eventually undetectable to the naked eye. This process of breaking down large plastic material into much smaller pieces is known as fragmentation. It is considered that microplastics might further degrade to be smaller in size, although the smallest microplastic reportedly detected in the oceans at present is 1.6 micrometres (6.3×10−5 in) in diameter. The prevalence of microplastics with uneven shapes suggests that fragmentation is a key source.Other sources: as a by-product/dust emission during wear and tear

There are countless sources of both primary and secondary microplastics. Microfibers, microplastic fibers that enter the environment from the washing of synthetic clothing. As they are used, tires, composed partly of synthetic Styrene Butadiene Rubber, will erode into tiny plastic and rubber particles. Furthermore, 2.0-5.0 mm plastic pellets, used to create other plastic products, often enter ecosystems due to spillages and other accidents. A Norwegian Environment Agency review report about microplastics published in early 2015 states it would be beneficial to classify these sources as primary, as long as microplastics from these sources are added from human society at the "start of the pipe", and their emissions are inherently a result of human material and product use and not secondary defragmentation in nature.Sources

Polystyrene foam beads on an Irish beach

The existence of microplastics in the environment is often established through aquatic studies. These include taking plankton samples, analyzing sandy and muddy sediments, observing vertebrate and invertebrate consumption, and evaluating chemical pollutant interactions. Through such methods, it has been shown that there are microplastics from multiple sources in the environment.

Microplastics could contribute up to 30% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch polluting the world’s oceans and, in many developed countries, are a bigger source of marine plastic pollution than the visible larger pieces of marine litter, according to a 2017 IUCN report.

Sewage treatment plants

Sewage treatment plants, also known as wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), remove contaminants from wastewater, primarily from household sewage, using various physical, chemical, and biological processes. Most plants in developed countries have both primary and secondary treatment stages. In the primary stage of treatment, physical processes are employed to remove oils, sand, and other large solids using conventional filters, clarifiers and settling tanks. Secondary treatment uses biological processes involving bacteria and protozoa to break down organic matter. Common secondary technologies are activated sludge systems, trickling filters and constructed wetlands. The optional tertiary treatment stage may include processes for nutrient removal (nitrogen and phosphorus) and disinfection.Microplastics have been detected in both the primary and secondary treatment stages of the plants. A study estimated that about one particle per liter of microplastics are being released back into the environment, with a removal efficiency of about 99.9%. A 2016 study showed that most microplastics are actually removed during the primary treatment stage where solid skimming and sludge settling are used. When these treatment facilities are functioning properly, the contribution of microplastics into oceans and surface water environments from WWTPs is not disproportionately large.

However, it is important to note that in certain countries sewage sludge is used for soil fertilizer, which exposes plastics in the sludge to the weather, sunlight, and other biological factors, causing fragmentation. As a result, microplastics from these biosolids often end up in storm drains and eventually into bodies of water. In addition, some studies show that microplastics do pass through filtration processes at some WWTPs (Microplastics as Contaminants, 2011). According to a study from the UK, samples taken from sewage sludge disposal-sites on the coasts of six continents contained an average one particle of microplastic per liter. A significant amount of these particles was of clothing fibers from washing machine effluent.

Car and truck tires

Wear and tear from tires significantly contributes to the flow of (micro-)plastics into the environment. Estimates of emissions of microplastics to the environment in Denmark are between 5,500 and 14,000 tonnes (6,100 and 15,400 tons) per year. Secondary microplastics (e.g. from car and truck tyres or footwear) are more important than primary microplastics by two orders of magnitude. The formation of microplastics from the degradation of larger plastics in the environment is not accounted for in the study.The estimated per capita emission ranges from 0.23 to 4.7 kg/year, with a global average of 0.81 kg/year. The emissions from car tires (100%) are substantially higher than those of other sources of microplastics, e.g., airplane tires (2%), artificial turf (12–50%), brake wear (8%) and road markings (5%). Emissions and pathways depend on local factors like road type or sewage systems. The relative contribution of tire wear and tear to the total global amount of plastics ending up in our oceans is estimated to be 5–10%. In air, 3–7% of the particulate matter (PM2.5) is estimated to consist of tire wear and tear, indicating that it may contribute to the global health burden of air pollution which has been projected by the World Health Organization (WHO) at 3 million deaths in 2012. The wear and tear also enters our food chain, but further research is needed to assess human health risks.

Cosmetics industry

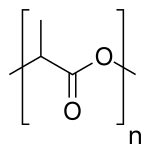

Some companies have replaced natural exfoliating ingredients with microplastics, usually in the form of "microbeads" or "micro-exfoliates". These products are typically composed of polyethylene, a common component of plastics, but they can also be manufactured from polypropylene, polyethylene terephthalate, and nylon. They are often found in face washes, hand soaps, and other personal care products, so the beads are usually washed into the sewage system immediately after use. Their small size prevents them from fully being retained by preliminary treatment screens at wastewater plants, thereby allowing some to enter rivers and oceans.Their small size prevents them from fully being retained by preliminary treatment screens at wastewater plants, thereby allowing some to enter rivers and oceans. In fact, wastewater treatment plants only remove an average of 95-99.9% of microbeads because of their small design . This leaves an average of 0-7 microbeads L^-1 being discharged. Considering that one treatment plant discharges 160 trillion liters of water per day, around 8 trillion microbeads are released into waterways every day. This averages out to around 8 trillion microbeads being released into waterways per day. This number doesn’t account for the sewage sludge that is reused as fertilizer after the waste water treatment that has been know to still contain these microbeads.This is an issue at the household level because it has been estimated that around 808 trillion beads per househous are discharged in a single day whether due to cosmetic exfoliates, face wash, toothpaste, or other sources. Although many companies have committed to phasing out the use of microbead in their products a research found that there are at least 80 different facial scrub products that are still being sold with microbeads as a main component. This fact contributes to the total of 80 metric tons of microbead discharge per year just by the United Kingdom alone. This not only has a negative impact on the wildlife and food chain but also in terms of toxicity because plastics such as microbeads have been proven to absorb dangerous chemicals such as pesticides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

Clothing

Studies have shown that many synthetic fibers, such as polyester, nylon and acrylics, can be shed from clothing and persist in the environment. Each garment in a load of laundry can shed more than 1,900 fibers of microplastics, with fleeces releasing the highest percentage of fibers, over 170% more than other garments. Washing machine manufacturers have also reviewed research into whether washing machine filters can reduce the amount of microfiber fibers that need to be treated by water treatment facilities. These microfibers have been found to persist throughout the food chain from zoo plankton to larger animals such as whales. The primary fiber that persist throughout the textile industry is polyester which is a cheap cotton alternative that can be easily manufactured. However, these types of fibers contribute greatly to the persistence to microplastics in terrestrial, aerial, and marine ecosystems. The process of washing clothes causes garments to lose an average of over 100 fibers per liter of water. This have been linked with health effects possibly caused by the release of monomers, dispersive dyes, mordants, and plasticisers from manufacturing. The commonality of these types of fibers in the common households has been shown to represent 33% of all fibers in indoor environments.Anthropomorphic fibers have been studied in both indoor and outdoor environments to study the concentration of these to see what the average human exposure to microfibers look like. The indoor concentration was 1.0 - 60.0 fibers/m^3 whereas the outdoor concentration was much lower at 0.3-1.5 fibers/m^3. The deposition rate indoors was 1586-11,130 fibers per day/m^3 which accumulates to around 190-670 fibers/mg of dust. The largest concern with these concentrations is that it increases exposure to children and the elderly which can cause adverse health effects.

Manufacturing

The manufacture of plastic products uses granules and small resin pellets as their raw material. In the United States, production increased from 2.9 million pellets in 1960 to 21.7 million pellets in 1987. Through accidental spillage during land or sea transport, inappropriate use as packing materials, and direct outflow from processing plants, these raw materials can enter aquatic ecosystems. In an assessment of Swedish waters using an 80 µm mesh, KIMO Sweden found typical microplastic concentrations of 150–2,400 microplastics per m3; in a harbor adjacent to a plastic production facility, the concentration was 102,000 per m3.Many industrial sites in which convenient raw plastics are frequently used are located near bodies of water. If spilled during production, these materials may leak into the surrounding environment, polluting waterways. “More recently, Operation Cleansweep (www.opcleansweep.org), a joint initiative of the American Chemistry Council and Society of the Plastics Industry, is aiming for industries to commit to zero pellet loss during their operations”. Overall, there is a significant lack of research conducted about specific industries and companies that contribute to microplastics pollution.

Fishing industry

Recreational and commercial fishing, marine vessels, and marine industries are all sources of plastic that can directly enter the marine environment, posing a risk to biota both as macroplastics, and as secondary microplastics following long-term degradation. Marine debris observed on beaches also arises from beaching of materials carried on in-shore and ocean currents. Fishing gear is a form of plastic debris with a marine source. Discarded or lost fishing gear, including plastic monofilament line and nylon netting, is typically neutrally buoyant and can therefore drift at variable depths within the oceans. Various countries have reported microplastics from the industry and other sources have been accumulating in different types of seafood. In Indonesia 55% of all fish species had evidence of manufactured debris similar to America which reported 67%. However, in Indonesia the majority of debris was plastic and in North America the majority was synthetic fibers found in clothing and some types of nets. The implication that fish are being contaminated with microplastic is that those plastics and chemicals will bioaccumulate in the food chain.One study analyzed the plastic-derived chemical called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in short-tailed shearwaters birds’ stomachs. They found that one fourth of the birds had higher-brominated congeners that are not naturally found in their pray. However, the PBDE got into the birds system through plastic that was found in the stomachs of the birds. Therefore it is not just the plastics that are being transferred through the food chain but the chemicals from the plastics as well.

Packaging and shipping

Shipping has significantly contributed to marine pollution. Some statistics indicate that in 1970, commercial shipping fleets around the world dumped over 23,000 tons of plastic waste into the marine environment. In 1988, an international agreement (MARPOL 73/78, Annex V) prohibited the dumping of waste from ships into the marine environment. However, shipping remains a dominant source of plastic pollution, having contributed around 6.5 million tons of plastic in the early 1990s. Research has shown that approximately 10% of the plastic found on the beaches in Hawaii are nurdles. In one incident on July 24th 2012, 150 tonnes of nurdles and other raw plastic material spilled from a shipping vessel off the coast near Hong Kong after a major storm. This waste from the Chinese company Sinopec were reported to have piled up in large quantities on beaches. While this is a large incident of spillage, researchers speculate that smaller accidents also occur and further contribute to marine microplastic pollution.Plastic water bottles

In one study, 93% of the bottled water from 11 different brands showed microplastic contamination. Per liter, researcher’s found an average of 325 microplastic particles. Of the tested brands, Nestle Pure Life and Gerolsteiner bottles contained the most microplastic with 930 and 807 microplastic particles per liter (MPP/L), respectively. San Pellegrino products showed the least quantity of microplastic densities. Compared to water from taps, water from plastic bottles contained twice as much microplastic. Some of the contamination likely comes from the process of bottling and packaging the water.Potential effects on the environment

Participants at the 2008 International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris at the University of Washington at Tacoma concluded that microplastics are a problem in the marine environment, based on:- the documented occurrence of microplastics in the marine environment,

- the long residence times of these particles (and, therefore, their likely buildup in the future), and

- their demonstrated ingestion by marine organisms.

Microplastics have been detected not just in marine but also in freshwater systems in three continents (Europe, North America and Asia). Samples collected across 29 Great Lakes tributaries from six states in the United States were found to contain plastic particles, 98% of which were microplastics ranging in size from 0.355mm to 4.75mm.

Biological integration into organisms

Microplastics can become embedded in animals' tissue through ingestion or respiration. Various annelid species, such as deposit-feeding lugworms (Arenicola marina), have been shown to have microplastics embedded in their gastrointestinal tracts. Many crustaceans, like the shore crab Carcinus maenas have been seen to integrate microplastics into both their respiratory and digestive tracts.Additionally, bottom feeders, such as benthic sea cucumbers, who are non-selective scavengers that feed on debris on the ocean floor, ingest large amounts of sediment. It has been shown that four species of sea cucumber (Thyonella gemmate, Holothuria floridana, H. grisea and Cucumaria frondosa) ingested between 2- and 20-fold more PVC fragments and between 2- and 138-fold more nylon line fragments (as much as 517 fibers per organism) based on plastic-to-sand grain ratios from each sediment treatment. These results suggest that individuals may be selectively ingesting plastic particles. This contradicts the accepted indiscriminate feeding strategy of sea cucumbers, and may occur in all presumed non-selective feeders when presented with microplastics.

Not only fish and free-living organisms can ingest microplastics. Scleractinian corals, which are primary reef-builders, have been shown to ingest microplastics under laboratory conditions. While the effects of ingestion on these corals has not been studied, corals can easily become stressed and bleach. Microplastics have been shown to stick to the exterior of the corals after exposure in the laboratory. The adherence to the outside of corals can potentially be harmful, because corals cannot handle sediment or any particulate matter on their exterior and slough it off by secreting mucus, and they expend a large amount of energy in the process, increasing the chances of mortality.

Zooplankton ingest microplastics beads (1.7–30.6 μm) and excrete fecal matter contaminated with microplastics. Along with ingestion, the microplastics stick to the appendages and exoskeleton of the zooplankton. Zooplankton, among other marine organisms, consume microplastics because they emit similar infochemicals, notably dimethyl sulfide, just as phytoplankton do. Plastics such as high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), and polypropylene (PP) produce dimethyl sulfide odors. These types of plastics are commonly found in plastic bags, bleach, food storage containers, and bottle caps.

It can take at least 14 days for microplastics to pass through an animal (as compared to a normal digestion periods of 2 days), but enmeshment of the particles in animals' gills can prevent elimination entirely. When microplastic-laden animals are consumed by predators, the microplastics are then incorporated into the bodies of higher trophic-level feeders. For example, scientists have reported plastic accumulation in the stomachs of lantern fish which are small filter feeders and are the main prey for commercial fish like tuna and swordfish. Microplastics also absorb chemical pollutants that can be transferred into the organism's tissues. Small animals are at risk of reduced food intake due to false satiation and resulting starvation or other physical harm from the microplastics.

A study done at the Argentinean coastline of the Rio de la Plata estuary, found the presence of microplastics in the guts of 11 species of coastal freshwater fish. These 11 species of fish represented four different feeding habits: detritivore, planktivore, omnivore and ichthyophagous.. This study is one of the few so far to show the ingestion of microplastics by freshwater organisms.

Humans

Fish is the primary source of protein for nearly one-fifth of the human population. The microplastics ingested by fish and crustaceans can be subsequently consumed by humans as the end of the food chain. In a study done at the State University of New York, 18 fish species were sampled and all species showed some level of plastics in their systems. Many additional researchers have found evidence that these fibers had become chemically associated with metals, polychlorinated biphenyls, and other toxic contaminants while in water. The microplastic-metal complex can then enter humans via consumption.The primary concern with human health in regards to microplastics is more directed towards the different toxic and carcinogenic chemicals used to make these plastics and what they carry. It has also been thought that microplastics can act as a vector for pathogens as well as heavy metals. More specifically, pregnant women in particular are in danger of causing birth defects to male enfants such as anogenital distance, penile width, and testicular descent. This comes from phthalate exposure and DEHP metabolites that interfere with the development of the male reproductive tract.

BPA is a commonly well known substance that is an ingredient used to harden plastic that can also cause a wide range of disorders. Cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and abnormalities in liver enzymes are a few disorders that can arise from even small exposure to this chemical. Although these effects have been more widely studied than other types of plastics it is still used in the production of many clothing (polyester).

Another dangerous ingredient is called Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) which is a flame retardant in many different types of plastics such as those used in microcircuits. This chemical has been linked to disrupts thyroid hormones balance, pituitary function, and infertility. The endocrine system is affected by TBBPA by disrupting the natural T3 functions with the nuclear suspension in pituitary and thyroid.

Many people can expect to come in contact with various different types of microplastics on a daily basis in aforementioned sources (see sources). However, the average citizen is exposed to microplastics through their various types of food included in a normal diet. For instance: Salt. Researchers in China tested three types of table salt samples available in supermarkets and found the presence of microplastics in all of them. Sea salt has the highest amounts of microplastics compared to lake salt and rock/well salt. Sea salt and rock salt which are commonly used table salts in Spain have also been found to contain microplastics. The most common type of microplastic found in both these studies was polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

An example of bioaccumulation in the food chain that leads to human exposure was a study done into the tissue samples of mussels to approximate concentration of microplastics. After research scientists estimate that an average citizen might be exposed to 123 MP articles/year/capita of microplastics through mussel consumption in the UK. Considering different diets it was also estimated that the microplastic exposure could go up to 4,620 particles/y/capita in countries with a higher shellfish consumption. However, it is also important to note that the humans on average are exposed to microplastics more in household dust than consuming mussels.

Buoyancy

Approximately half of the plastic material introduced to the marine environment is buoyant, but fouling by organisms can cause plastic debris to sink to the sea floor, where it may interfere with sediment-dwelling species and sedimental gas exchange processes. Several factors contribute to microplastic’s buoyancy, including the density of the plastic it is composed as well as the size and shape of the microplastic fragments themselves. Microplastics can also form a buoyant biofilm layer on the ocean’s surface. Buoyancy changes in relation to ingestion of microplastics have been clearly observed in autotrophs because the absorption can interfere with photosynthesis and subsequent gas levels. However, this issue is of more importance for larger plastic debris.| Plastic Type | Abbreviation | Density (g/cm3) |

| Polystyrene | PS | 1.04-1.08 |

| Expanded Polystyrene | EPS | 0.01-0.04 |

| Low-density Polyethylene | LDPE | 0.94-0.98 |

| High-density Polyethylene | HDPE | 0.94-0.98 |

| Polyamide | PA | 1.13-1.16 |

| Polypropylene | PP | 0.85-0.92 |

| Acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene | ABS | 1.04-1.06 |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene | PTFE | 2.10-2.30 |

| Cellulose Acetate | CA | 1.30 |

| Polycarbonate | PC | 1.20-1.22 |

| Polymethyl methacrylate | PMMA | 1.16-1.20 |

| Polyvinyl chloride | PVC | 1.38-1.41 |

| Polyethylene terephthalate | PET | 1.38-1.41 |

Persistent organic pollutants

Plastic particles may highly concentrate and transport synthetic organic compounds (e.g. persistent organic pollutants, POPs), commonly present in the environment and ambient sea water, on their surface through adsorption. Microplastics can act as carriers for the transfer of POPs from the environment to organisms.Additives added to plastics during manufacture may leach out upon ingestion, potentially causing serious harm to the organism. Endocrine disruption by plastic additives may affect the reproductive health of humans and wildlife alike.

Plastics, polymers derived from mineral oils, are virtually non-biodegradable. However, renewable natural polymers are now in development which can be used for the production of biodegradable materials similar to that of oil-based polymers.

Where microplastics can be found

Oceans

There is truly a staggering amount of microplastics in our world’s oceans. Though there is debate over exactly how much microplastic is in the world’s oceans a 2015 study estimated that there was between 93 and 236 thousand metric tons of microplastics in the world’s oceans. A study of the distribution of Eastern Pacific Ocean surface plastic debris helps to illustrate how the concentration of plastics in the ocean is on the rise. Though the study admits further research is needed to predict trends in ocean plastic concentration, the study, using data on surface plastic concentration (pieces of plastic km-2) from 1972-1985 n=60 and 2002-2012 n=457 within the same plastic accumulation zone, found the mean plastic concentration increase between the two sets of data, including a 10-fold increase of 18,160 to 189,800 pieces of plastic km-2. And though this study is based on data of surface plastic concentration, not specifically microplastic, additional research has found microplastics to account for 92% of plastic debris on the ocean’s surface, which adds context to the study.Freshwater ecosystems

Though there have only been a few studies of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems, microplastics are being increasingly detected in the world’s aquatic environments. The first study on microplastics in freshwater ecosystems was published in 2011 that found an average of 37.8 fragments per square meter of Lake Huron sediment samples. Additionally, studies have found MP (microplastic) to be present in all of the Great Lakes with an average concentration of 43,000 MP particle km-2. Microplastics have also been detected in freshwater ecosystems outside of the United States. The highest concentration of microplastic ever discovered in a studied freshwater ecosystem was recorded in the Rhine river at 4000 MP particles kg-1.Soil

A substantial portion of microplastics are expected to end up in the world’s soil, yet very little research has been conducted on microplastics in soil. There some speculation that fibrous secondary microplastics from washing machine could end up in soil through the failure of water treatment plants to completely filter out all of the microplastic fibers. Furthermore, geophagous soil fauna, such as earthworms, mites, and collembolan could contribute to the amount of secondary microplastic present in soil by converting consumed plastic debris into microplastic via digestive processes. But, further research is needed. There is concrete data linking one the use of organic waste materials to synthetic fibers being found in the soil; but most studies on plastics in soil merely reports its presence and do not quantify how much there is or where it came from.In the air

Airborne microplastics have been detected in the atmosphere, as well as indoors and outdoors. A 2017 study found indoor airborne microfiber concentrations between 1.0-60.0 microfibers per cubic meter (33% of which were found to be microplastics). Another study looked at microplastic in the street dust of Tehran Iran and found 2649 particles of microplastic within ten samples of street dust, with ranging samples concentrations from 83 particle – 605 particles (+/- 10) per 30.0 g of street dust. However, much like freshwater ecosystems and soil, more studies are needed to understand the full impact and significance of airborne microplastics.Proposed solutions

Some researchers have proposed incinerating plastics to use as energy, which is known as energy recovery. As opposed to losing the energy from plastics into the atmosphere in landfills, this process turns some of the plastics back into energy that we can use. However, as opposed to recycling, this method does not diminish the amount of plastic material that is produced. Therefore, recycling plastics is a more beneficial solution.Increasing education through recycling campaigns is another proposed solution for microplastic contamination. While this would be a smaller scale solution, education has been shown to reduce littering, especially in urban environments where there are often large concentrations of plastic waste. If recycling efforts are increased, a cycle of plastic use and reuse would be created to decrease our waste output and production of new raw materials. In order to achieve this, states would need to employ stronger infrastructure and investment around recycling. Some advocate for improving recycling technology to be able to recycle smaller plastics to reduce the need for production of new plastics.

Biodegradation is another possible solution to large amounts of microplastic waste. In this process, microorganisms consume and decompose synthetic polymers with using degrading enzymes. These plastics can then be used in the form of energy and as a source of carbon once broken down. The microbes could potentially be used to treat sewage wastewater, which would decrease the amount of microplastics that pass through into the surrounding environments.

Policy and legislation

With increasing awareness of the detrimental effects of microplastics on the environment, groups are now advocating for the removal and ban of microplastics from various products. One such campaign is "Beat the Microbead", which focuses on removing plastics from personal care products. The Adventurers and Scientists for Conservation run the Global Microplastics Initiative, a project to collect water samples to provide scientists with better data about microplastic dispersion in the environment. UNESCO has sponsored research and global assessment programs due to the trans-boundary issue that microplastic pollution constitutes. These environmental groups will keep pressuring companies to remove plastics from their products in order to maintain healthy ecosystems.- United States

On July 25th, 2018, a microplastic reduction amendment was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. The legislation, as part of the Save our Seas Act designed to combat marine pollution, aims to support the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration's Marine Debris Program. In particular, the amendment is geared towards promoting NOAA’s Great Lakes Land-Based Marine Debris Action Plan to increase testing, cleanup, and education around plastic pollution in the Great Lakes.

Japan

On June 15th, 2018, the Japanese government passed a bill with the goal of reducing microplastic production and pollution, especially in aquatic environments. Proposed by the Environment Ministry and passed unanimously by the Upper House, this is also the first bill to pass in Japan that is specifically targeted at reducing microplastic production, specifically in the personal care industry with products such as face wash and toothpaste. This law is revised from previous legislation, which focused on removing plastic marine debris. It also focuses on increasing education and public awareness surrounding recycling and plastic waste. The Environment Ministry has also proposed a number of recommendations for methods to monitor microplastic quantities in the ocean (Recommendations, 2018). However, the legislation does not specify any penalties for those who continue manufacturing products with microplastics.

United Kingdom

The “Environmental Protection (Microbeads) (England) Regulations 2017” law from passed by the UK government bans the production of any rinse-off personal care products (such as exfoliants) containing microbeads. This particular law denotes specific penalties when it is not obeyed. Those who do not comply are required to pay a fine. In the event that a fine is not paid, product manufacturers may receive a stop notice, which prevents the manufacturer from continuing production until they have followed regulation preventing the use of microbeads. Criminal proceedings may occur if the stop notice is ignored.

Action for creating awareness

On April 11, 2013 in order to create awareness, artist Maria Cristina Finucci founded The Garbage patch state under the patronage of UNESCO and the Italian Ministry of the Environment.The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched its "Trash-Free Waters" initiative in 2013 to prevent single-use plastic wastes from ending up in waterways and ultimately the ocean. EPA collaborates with the United Nations Environment Programme–Caribbean Environment Programme (UNEP-CEP) and the Peace Corps to reduce and also remove trash in the Caribbean Sea. EPA has also funded various projects in the San Francisco Bay Area including one that is aimed at reducing the use of single-use plastics such as disposable cups, spoons and straws, from three University of California campuses.

Additionally, there are many organizations advocating action to counter microplastics and that are spreading microplastic awareness. One such group is the Florida Microplastic Awareness Project (FMAP), a group of volunteers who search for microplastics in costal water samples.

Cleanup

Computer modelling done by The Ocean Cleanup, a Netherlands foundation, has suggested that collecting devices placed nearer to the coasts could remove about 31% of the microplastics in the area. In addition, some bacteria have evolved to eat plastic, and some bacteria species have been genetically modified to eat (certain types of) plastics.On September 9, 2018, The Ocean Cleanup launched the world’s first ocean cleanup system, 001 aka “Wilson” and is being deployed to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. System 001 is 600 meters long that acts as a U-shaped skiff that uses natural oceanic currents to concentrate plastic and other debris on the ocean’s surface into a confined area for extraction by vessels.