Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous or folk medicine) comprises medical aspects of traditional knowledge that developed over generations within the folk beliefs of various societies before the era of modern medicine. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines traditional medicine as "the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness". Traditional medicine is often contrasted with scientific medicine.

In some Asian and African countries, up to 80% of the population relies on traditional medicine for their primary health care needs. When adopted outside its traditional culture, traditional medicine is often considered a form of alternative medicine. Practices known as traditional medicines include traditional European medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional indigenous Mayongia magic and medicine(Assam), traditional indigenous medicine of Assam and rest of NE India, nattuvaidyam (indigenous medicine practised in south India), traditional Korean medicine, traditional African medicine, Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, Unani, ancient Iranian Medicine, Iranian (Persian), Islamic medicine, Muti, and Ifá. Scientific disciplines which study traditional medicine include herbalism, ethnomedicine, ethnobotany, and medical anthropology.

The WHO notes, however, that "inappropriate use of traditional medicines or practices can have negative or dangerous effects" and that "further research is needed to ascertain the efficacy and safety" of such practices and medicinal plants used by traditional medicine systems. As a result, the WHO has implemented a nine-year strategy to "support Member States in developing proactive policies and implementing action plans that will strengthen the role traditional medicine plays in keeping populations healthy."

Usage and history

Classical history

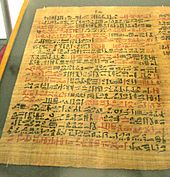

In the written record, the study of herbs dates back 5,000 years to the ancient Sumerians, who described well-established medicinal uses for plants. In Ancient Egyptian medicine, the Ebers papyrus from c. 1552 BC records a list of folk remedies and magical medical practices. The Old Testament also mentions herb use and cultivation in regards to Kashrut.

Many herbs and minerals used in Ayurveda were described by ancient Indian herbalists such as Charaka and Sushruta during the 1st millennium BC. The first Chinese herbal book was the Shennong Bencao Jing, compiled during the Han Dynasty but dating back to a much earlier date, which was later augmented as the Yaoxing Lun (Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs) during the Tang Dynasty. Early recognised Greek compilers of existing and current herbal knowledge include Pythagoras and his followers, Hippocrates, Aristotle, Theophrastus, Dioscorides and Galen.

Roman sources included Pliny the Elder's Natural History and Celsus's De Medicina. Pedanius Dioscorides drew on and corrected earlier authors for his De Materia Medica, adding much new material; the work was translated into several languages, and Turkish, Arabic and Hebrew names were added to it over the centuries. Latin manuscripts of De Materia Medica were combined with a Latin herbal by Apuleius Platonicus (Herbarium Apuleii Platonici) and were incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon codex Cotton Vitellius C.III. These early Greek and Roman compilations became the backbone of European medical theory and were translated by the Persian Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā, 980–1037), the Persian Rhazes (Rāzi, 865–925) and the Jewish Maimonides.

Some fossils have been used in traditional medicine since antiquity.

Medieval and later

Arabic indigenous medicine developed from the conflict between the magic-based medicine of the Bedouins and the Arabic translations of the Hellenic and Ayurvedic medical traditions. Spanish medicine was influenced by the Arabs from 711 to 1492. Islamic physicians and Muslim botanists such as al-Dinawari and Ibn al-Baitar significantly expanded on the earlier knowledge of materia medica. The most famous Persian medical treatise was Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine, which was an early pharmacopoeia and introduced clinical trials. The Canon was translated into Latin in the 12th century and remained a medical authority in Europe until the 17th century. The Unani system of traditional medicine is also based on the Canon.

Translations of the early Roman-Greek compilations were made into German by Hieronymus Bock whose herbal, published in 1546, was called Kreuter Buch. The book was translated into Dutch as Pemptades by Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585), and from Dutch into English by Carolus Clusius, (1526–1609), published by Henry Lyte in 1578 as A Nievve Herball. This became John Gerard's (1545–1612) Herball or General Historie of Plantes. Each new work was a compilation of existing texts with new additions.

Women's folk knowledge existed in undocumented parallel with these texts. Forty-four drugs, diluents, flavouring agents and emollients mentioned by Dioscorides are still listed in the official pharmacopoeias of Europe. The Puritans took Gerard's work to the United States where it influenced American Indigenous medicine.

Francisco Hernández, physician to Philip II of Spain spent the years 1571–1577 gathering information in Mexico and then wrote Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus, many versions of which have been published including one by Francisco Ximénez. Both Hernandez and Ximenez fitted Aztec ethnomedicinal information into the European concepts of disease such as "warm", "cold", and "moist", but it is not clear that the Aztecs used these categories. Juan de Esteyneffer's Florilegio medicinal de todas las enfermedas compiled European texts and added 35 Mexican plants.

Martín de la Cruz wrote an herbal in Nahuatl which was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano as Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis or Codex Barberini, Latin 241 and given to King Carlos V of Spain in 1552. It was apparently written in haste and influenced by the European occupation of the previous 30 years. Fray Bernardino de Sahagún's used ethnographic methods to compile his codices that then became the Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, published in 1793. Castore Durante published his Herbario Nuovo in 1585 describing medicinal plants from Europe and the East and West Indies. It was translated into German in 1609 and Italian editions were published for the next century.

Colonial America

In 17th and 18th-century America, traditional folk healers, frequently women, used herbal remedies, cupping and leeching. Native American traditional herbal medicine introduced cures for malaria, dysentery, scurvy, non-venereal syphilis, and goiter problems. Many of these herbal and folk remedies continued on through the 19th and into the 20th century, with some plant medicines forming the basis for modern pharmacology.[22]

Modern usage

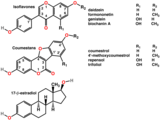

The prevalence of folk medicine in certain areas of the world varies according to cultural norms. Some modern medicine is based on plant phytochemicals that had been used in folk medicine. Researchers state that many of the alternative treatments are "statistically indistinguishable from placebo treatments".

Knowledge transmission and creation

Indigenous medicine is generally transmitted orally through a community, family and individuals until "collected". Within a given culture, elements of indigenous medicine knowledge may be diffusely known by many, or may be gathered and applied by those in a specific role of healer such as a shaman or midwife. Three factors legitimize the role of the healer – their own beliefs, the success of their actions and the beliefs of the community. When the claims of indigenous medicine become rejected by a culture, generally three types of adherents still use it – those born and socialized in it who become permanent believers, temporary believers who turn to it in crisis times, and those who only believe in specific aspects, not in all of it.

Definition and terminology

Traditional medicine may sometimes be considered as distinct from folk medicine, and the considered to include formalized aspects of folk medicine. Under this definition folk medicine are longstanding remedies passed on and practiced by lay people. Folk medicine consists of the healing practices and ideas of body physiology and health preservation known to some in a culture, transmitted informally as general knowledge, and practiced or applied by anyone in the culture having prior experience.

Folk medicine

Many countries have practices described as folk medicine which may coexist with formalized, science-based, and institutionalized systems of medical practice represented by conventional medicine. Examples of folk medicine traditions are traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, Arabic indigenous medicine, Uyghur traditional medicine, Japanese Kampō medicine, traditional Aboriginal bush medicine, Native Hawaiian Lāʻau lapaʻau, and Georgian folk medicine, among others.

Australian bush medicine

Generally, bush medicine used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia is made from plant materials, such as bark, leaves and seeds, although animal products may be used as well. A major component of traditional medicine is herbal medicine, which is the use of natural plant substances to treat or prevent illness.

Native American medicine

American Native and Alaska Native medicine are traditional forms of healing that have been around for thousands of years.

Nattuvaidyam

Nattuvaidyam was a set of indigenous medical practices that existed in India before the advent of allopathic or western medicine. These practices had different set of principles and ideas of the body, health and disease. There were overlaps and borrowing of ideas, medicinal compounds used and techniques within these practices. Some of these practices had written texts in vernacular languages like Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu, etc. while others were handed down orally through various mnemonic devices. Ayurveda was one kind of nattuvaidyam practised in south India. The others were kalarichikitsa (related to bone setting and musculature), marmachikitsa (vital spot massaging), ottamoolivaidyam (single dose medicine or single time medication), chintamanivaidyam and so on. When the medical system was revamped in twentieth century India, many of the practices and techniques specific to some of these diverse nattuvaidyam was included in Ayurveda.

Home remedies

A home remedy (sometimes also referred to as a granny cure) is a treatment to cure a disease or ailment that employs certain spices, herbs, vegetables, or other common items. Home remedies may or may not have medicinal properties that treat or cure the disease or ailment in question, as they are typically passed along by laypersons (which has been facilitated in recent years by the Internet). Many are merely used as a result of tradition or habit or because they are effective in inducing the placebo effect.

One of the more popular examples of a home remedy is the use of chicken soup to treat respiratory infections such as a cold or mild flu. Other examples of home remedies include duct tape to help with setting broken bones; and duct tape or superglue to treat plantar warts; and Kogel mogel to treat sore throat. In earlier times, mothers were entrusted with all but serious remedies. Historic cookbooks are frequently full of remedies for dyspepsia, fevers, and female complaints. Components of the aloe vera plant are used to treat skin disorders. Many European liqueurs or digestifs were originally sold as medicinal remedies. In Chinese folk medicine, medicinal congees (long-cooked rice soups with herbs), foods, and soups are part of treatment practices.

Criticism

Safety concerns

Although 130 countries have regulations on folk medicines, there are risks associated with the use of them (i.e. zoonosis, mainly as some traditional medicines still use animal-based substances). It is often assumed that because supposed medicines are natural that they are safe, but numerous precautions are associated with using herbal remedies.

Use of endangered species

Endangered animals, such as the slow loris, are sometimes killed to make traditional medicines.

Shark fins have also been used in traditional medicine, and although their effectiveness has not been proven, it is hurting shark populations and their ecosystem.

The illegal ivory trade can partially be traced back to buyers of traditional Chinese medicine. Demand for ivory is a huge factor in the poaching of endangered species such as rhinos and elephants.