Biocentrism (from Greek βίος bios, "life" and κέντρον kentron, "center"), in a political and ecological sense, as well as literally, is an ethical point of view that extends inherent value to all living things. It is an understanding of how the earth works, particularly as it relates to biodiversity. It stands in contrast to anthropocentrism, which centers on the value of humans. The related ecocentrism extends inherent value to the whole of nature.

Biocentrism does not imply the idea of equality among the animal kingdom, for no such notion can be observed in nature. Biocentric thought is nature based, not human based.

Advocates of biocentrism often promote the preservation of biodiversity, animal rights, and environmental protection. The term has also been employed by advocates of "left biocentrism", which combines deep ecology with an "anti-industrial and anti-capitalist" position (according to David Orton et al.).

Definition

The term biocentrism encompasses all environmental ethics that "extend the status of moral object from human beings to all living things in nature". Biocentric ethics calls for a rethinking of the relationship between humans and nature. It states that nature does not exist simply to be used or consumed by humans, but that humans are simply one species amongst many,[6] and that because we are part of an ecosystem, any actions which negatively affect the living systems of which we are a part adversely affect us as well, whether or not we maintain a biocentric worldview. Biocentrists observe that all species have inherent value, and that humans are not "superior" to other species in a moral or ethical sense.The four main pillars of a biocentric outlook are:

- Humans and all other species are members of Earth's community.

- All species are part of a system of interdependence.

- All living organisms pursue their own "good" in their own ways.

- Human beings are not inherently superior to other living things.[8]

Relationship with animals and environment

Biocentrism views individual species as parts of the living biosphere. It observes the consequences of reducing biodiversity on both small and large scales and points to the inherent value all species have to the environment.The environment is seen for what it is; the biosphere within which we live and depend on its diversity for our health. From these observations the ethical points are raised.

History and development

Biocentric ethics differs from classical and traditional ethical thinking. Rather than focusing on strict moral rules, as in Classical ethics, it focuses on attitudes and character. In contrast with traditional ethics, it is nonhierarchical and gives priority to the natural world rather than to humankind exclusively.[9]Biocentric ethics includes Albert Schweitzer's ethics of "Reverence for Life", Peter Singer's ethics of Animal Liberation and Paul Taylor's ethics of biocentric egalitarianism.[5]

Albert Schweitzer's "reverence for life" principle was a precursor of modern biocentric ethics.[5] In contrast with traditional ethics, the ethics of "reverence for life" denies any distinction between "high and low" or "valuable and less valuable" life forms, dismissing such categorization as arbitrary and subjective.[5] Conventional ethics concerned itself exclusively with human beings—that is to say, morality applied only to interpersonal relationships—whereas Schweitzer's ethical philosophy introduced a "depth, energy, and function that differ[s] from the ethics that merely involved humans".[5] "Reverence for life" was a "new ethics, because it is not only an extension of ethics, but also a transformation of the nature of ethics".[5]

Similarly, Peter Singer argues that non-human animals deserve the same equality of consideration that we extend to human beings.[10] His argument is roughly as follows:

- Membership in the species Homo sapiens is the only criterion of moral importance that includes all humans and excludes all non-humans.

- Using membership in the species Homo sapiens as a criterion of moral importance is completely arbitrary.

- Of the remaining criteria we might consider, only sentience is a plausible criterion of moral importance.

- Using sentience as a criterion of moral importance entails that we extend the same basic moral consideration (i.e. "basic principle of equality") to other sentient creatures that we do to human beings.

- Therefore, we ought to extend to animals the same equality of consideration that we extend to human beings.[10]

- Humans are members of a community of life along with all other species, and on equal terms.

- This community consists of a system of interdependence between all members, both physically, and in terms of relationships with other species.

- Every organism is a "teleological centre of life", that is, each organism has a purpose and a reason for being, which is inherently "good" or "valuable".

- Humans are not inherently superior to other species.

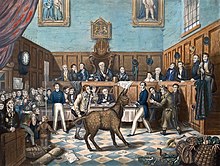

If we choose to let conjecture run wild, then animals, our fellow brethren in pain, diseases, death, suffering and famine—our slaves in the most laborious works, our companions in our amusement—they may partake of our origin in one common ancestor—we may be all netted together.In 1859, Charles Darwin published his book On the Origin of Species. This publication sparked the beginning of biocentrist views by introducing evolution and "its removal of humans from their supernatural origins and placement into the framework of natural laws".[15]

The work of Aldo Leopold has also been associated with biocentrism.[16] The essay The Land Ethic in Leopold's book Sand County Almanac (1949) points out that although throughout history women and slaves have been considered property, all people have now been granted rights and freedoms.[17] Leopold notes that today land is still considered property as people once were. He asserts that ethics should be extended to the land as "an evolutionary possibility and an ecological necessity".[18] He argues that while people's instincts encourage them to compete with others, their ethics encourage them to co-operate with others.[18] He suggests that "the land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land".[18] In a sense this attitude would encourage humans to co-operate with the land rather than compete with it.

Outside of formal philosophical works biocentric thought is common among pre-colonial tribal peoples who knew no world other than the natural world.

In law

The paradigm of biocentrism and the values that it promotes are beginning to be used in law.In recent years, cities in Maine, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire and Virginia have adopted laws that protect the rights of nature.[19] The purpose of these laws is to prevent the degradation of nature; especially by corporations who may want to exploit natural resources and land space, and to also use the environment as a dumping ground for toxic waste.[19]

The first country to include rights of nature in its constitution is Ecuador[20] (See 2008 Constitution of Ecuador). Article 71 states that nature "has the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes".[21]

In religion

Islam

In Islam: In Islam, biocentric ethics stem from the belief that all of creation belongs to Allah (God), not humans, and to assume that non-human animals and plants exist merely to benefit humankind leads to environmental destruction and misuse.[22] As all living organisms exist to praise God, human destruction of other living things prevents the earth's natural and subtle means of praising God. The Qur'an acknowledges that humans are not the only all-important creatures and emphasizes a respect for nature. Muhammad was once asked whether there would be a reward for those who show charity to nature and animals, to which he replied, "for charity shown to each creature with a wet heart [i.e. that is alive], there is a reward."[23]Hinduism

In Hinduism: Hinduism contains many elements of biocentrism. In Hinduism, humans have no special authority over other creatures, and all living things have souls ('atman'). Brahman (God) is the "efficient cause" and Prakrti (nature), is the "material cause" of the universe.[22] However, Brahman and Prakrti are not considered truly divided: "They are one in [sic] the same, or perhaps better stated, they are the one in the many and the many in the one."[22]However, while Hinduism does not give the same direct authority over nature that the Judeo-Christian God grants, they are subject to a "higher and more authoritative responsibility for creation". The most important aspect of this is the doctrine of Ahimsa (non-violence). The Yājñavalkya Smṛti warns, "the wicked person who kills animals which are protected has to live in hell fire for the days equal to the number of hairs on the body of that animal".[22] The essential aspect of this doctrine is the belief that the Supreme Being incarnates into the forms of various species. The Hindu belief in Saṃsāra (the cycle of life, death and rebirth) encompasses reincarnation into non-human forms. It is believed that one lives 84,000 lifetimes before one becomes a human. Each species is in this process of samsara until one attains moksha (liberation).

Another doctrinal source for the equal treatment of all life is found in the Rigveda. The Rigveda states that trees and plants possess divine healing properties. It is still popularly believed that every tree has a Vriksa-devata (a tree deity).Trees are ritually worshiped through prayer, offerings, and the sacred thread ceremony. The Vriksa-devata worshiped as manifestations of the Divine. Tree planting is considered a religious duty.[22]

Jainism

In Jainism: The Jaina tradition exists in tandem with Hinduism and shares many of its biocentric elements.[24]Ahimsa (non-violence), the central teaching of Jainism, means more than not hurting other humans.[25] It means intending not to cause physical, mental or spiritual harm to any part of nature. In the words of Mahavira: ‘You are that which you wish to harm.’[25] Compassion is a pillar of non-violence. Jainism encourages people to practice an attitude of compassion towards all life.

The principle of interdependence is also very important in Jainism. This states that all of nature is bound together, and that "if one does not care for nature one does not care for oneself.".[25]

Another essential Jain teaching is self-restraint. Jainism discourages wasting the gifts of nature, and encourages its practitioners to reduce their needs as far as possible. Gandhi, a great proponent of Jainism, once stated "There is enough in this world for human needs, but not for human wants."[25]

Buddhism

In Buddhism: The Buddha's teachings encourage people "to live simply, to cherish tranquility, to appreciate the natural cycle of life".[26] Buddhism emphasizes that everything in the universe affects everything else. "Nature is an ecosystem in which trees affect climate, the soil, and the animals, just as the climate affects the trees, the soil, the animals and so on. The ocean, the sky, the air are all interrelated, and interdependent—water is life and air is life."[26]Although this holistic approach is more ecocentric than biocentric, it is also biocentric, as it maintains that all living things are important and that humans are not above other creatures or nature. Buddhism teaches that "once we treat nature as our friend, to cherish it, then we can see the need to change from the attitude of dominating nature to an attitude of working with nature—we are an intrinsic part of all existence rather than seeing ourselves as in control of it."[26]

Criticism

Biocentrism has faced criticism for a number of reasons. Some of this criticism grows out of the concern that biocentrism is an anti-human paradigm and that it will not hesitate to sacrifice human well-being for the greater good.[20] Biocentrism has also been criticized for its individualism; emphasizing too much on the importance of individual life and neglecting the importance of collective groups, such as an ecosystem.[27]A more complex form of criticism focuses on the contradictions of biocentrism. Opposed to anthropocentrism, which sees humans as having a higher status than other species,[28] biocentrism puts humans on a par with the rest of nature, and not above it.[29] In his essay A Critique of Anti-Anthropocentric Biocentrism Richard Watson suggests that if this is the case, then "Human ways—human culture—and human actions are as natural as the ways in which any other species of animals behaves".[30] He goes on to suggest that if humans must change their behavior to refrain from disturbing and damaging the natural environment, then that results in setting humans apart from other species and assigning more power to them.[30] This then takes us back to the basic beliefs of anthropocentrism. Watson also claims that the extinction of species is "Nature's way"[31] and that if humans were to instigate their own self-destruction by exploiting the rest of nature, then so be it. Therefore, he suggests that the real reason humans should reduce their destructive behavior in relation to other species is not because we are equals but because the destruction of other species will also result in our own destruction.[32] This view also brings us back to an anthropocentric perspective.