| EPA | |

Seal of the Environmental Protection Agency

| |

Flag of the Environmental Protection Agency

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | December 2, 1970 |

| Headquarters | William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building Washington, D.C., U.S. 38.8939°N 77.0289°WCoordinates: 38.8939°N 77.0289°W |

| Employees | 14,172 (2018) |

| Annual budget | $8.1 billion (2018) |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | www |

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government for environmental protection. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970 and it began operation on December 2, 1970, after Nixon signed an executive order. The order establishing the EPA was ratified by committee hearings in the House and Senate. The agency is led by its Administrator, who is appointed by the President and approved by Congress. The current acting Administrator following the resignation of Scott Pruitt is Deputy Administrator Andrew Wheeler. The EPA is not a Cabinet department, but the Administrator is normally given cabinet rank.

The EPA has its headquarters in Washington, D.C., regional offices for each of the agency's ten regions, and 27 laboratories. The agency conducts environmental assessment, research, and education. It has the responsibility of maintaining and enforcing national standards under a variety of environmental laws, in consultation with state, tribal, and local governments. It delegates some permitting, monitoring, and enforcement responsibility to U.S. states and the federally recognized tribes. EPA enforcement powers include fines, sanctions, and other measures. The agency also works with industries and all levels of government in a wide variety of voluntary pollution prevention programs and energy conservation efforts.

In 2018, the agency had 14,172 full-time employees. More than half of EPA's employees are engineers, scientists, and environmental protection specialists; other employees include legal, public affairs, financial, and information technologists. In 2017 the Trump administration proposed a 31% cut to the EPA's budget to $5.7 billion from $8.1 billion and to eliminate a quarter of the agency jobs. However, this cut was not approved by Congress.

The Environmental Protection Agency can only act under statutes, which are the authority of laws passed by Congress. Congress must approve the statute and they also have the power to authorize or prohibit certain actions, which the EPA has to implement and enforce. Appropriations statutes authorize how much money the agency can spend each year to carry out the approved statutes. The Environmental Protection Agency has the power to issue regulations. A regulation is a standard or rule written by the agency to interpret the statute, apply it in situations and enforce it. Congress allows the EPA to write regulations in order to solve a problem, but the agency must include a rationale of why the regulations need to be implemented. The regulations can be challenged by the Courts, where the regulation is overruled or confirmed. Many public health and environmental groups advocate for the agency and believe that it is creating a better world. Other critics believe that the agency commits government overreach by adding unnecessary regulations on business and property owners.

History

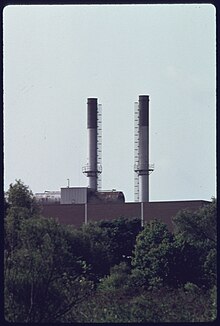

Stacks emitting smoke from burning discarded automobile batteries, photo taken in Houston in 1972 by Marc St. Gil, official photographer of recently founded EPA

Same smokestacks in 1975 after the plant was closed in a push for greater environmental protection

Beginning in the late 1950s and through the 1960s, Congress reacted

to increasing public concern about the impact that human activity could

have on the environment. Senator James E. Murray introduced a bill, the Resources and Conservation Act (RCA) of 1959, in the 86th Congress. The 1962 publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson alerted the public about the detrimental effects on the environment of the indiscriminate use of pesticides.

In the years following, similar bills were introduced and

hearings were held to discuss the state of the environment and

Congress's potential responses. In 1968, a joint House–Senate colloquium

was convened by the chairmen of the Senate Committee on Interior and

Insular Affairs, Senator Henry M. Jackson, and the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, Representative George P. Miller,

to discuss the need for and means of implementing a national

environmental policy. In the colloquium, some members of Congress

expressed a continuing concern over federal agency actions affecting the

environment.

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) was modeled on the Resources and Conservation Act of 1959 (RCA).

RCA would have established a Council on Environmental Quality in the

office of the President, declared a national environmental policy, and

required the preparation of an annual environmental report.

President Nixon signed NEPA into law on January 1, 1970. The law created the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in the Executive Office of the President.

NEPA required that a detailed statement of environmental impacts be

prepared for all major federal actions significantly affecting the

environment. The "detailed statement" would ultimately be referred to as

an environmental impact statement (EIS).

Ruckelshaus sworn in as first EPA Administrator.

On July 9, 1970, Nixon proposed an executive reorganization

that consolidated many environmental responsibilities of the federal

government under one agency, a new Environmental Protection Agency.

This proposal included merging antipollution programs from a number of

departments, such as the combination of pesticide programs from the

United States Department of Agriculture, Department of Interior, and

U.S. Department of Interior.

After conducting hearings during that summer, the House and Senate

approved the proposal. The EPA was created 90 days before it had to

operate, and officially opened its doors on December 2, 1970. The agency's first Administrator, William Ruckelshaus, took the oath of office on December 4, 1970. In its first year, the EPA had a budget of $1.4 billion and 5,800 employees.

At its start, the EPA was primarily a technical assistance agency that

set goals and standards. Soon, new acts and amendments passed by

Congress gave the agency its regulatory authority.

EPA staff recall that in the early days there was "an enormous

sense of purpose and excitement" and the expectation that "there was

this agency which was going to do something about a problem that clearly

was on the minds of a lot of people in this country," leading to tens

of thousands of resumes from those eager to participate in the mighty

effort to clean up America's environment.

When EPA first began operation, members of the private sector

felt strongly that the environmental protection movement was a passing

fad. Ruckelshaus stated that he felt pressure to show a public which was

deeply skeptical about government's effectiveness, that EPA could

respond effectively to widespread concerns about pollution.

Soon after the EPA was created, Congress enacted the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972, better known as the Clean Water Act.

This act established a national framework for addressing water quality

to be implemented by agency in partnership with the states.

In 1972, Congress also amended the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, requiring the newly formed EPA to measure every pesticide's risks against its potential benefits. Four years later, in October 1976,Congress passed the Toxic Substances Control Act, which like FIFRA related to commercial products rather than pollution.

This act gave the EPA the authority to gather information on chemicals

and require producers to test them, gave it the ability to regulate

chemical production and use (with specific mention of PCBs), and

required the agency to create the National Inventory listing of

chemicals.

The same year, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act was passed, significantly amending the Solid Waste Disposal Act of 1965.

It tasked the EPA with setting national goals for waste disposal,

conserving energy and natural resources, reducing waste, and ensuring

environmentally sound management of waste. Accordingly, the agency

developed regulations for solid and hazardous waste that were to be

implemented in collaboration with states.

In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive Environmental

Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, nicknamed “Superfund,” which

enabled the EPA to cast a wider net for parties responsible for sites

contaminated by previous hazardous waste disposal (such as Love Canal)

and established a funding mechanism for assessment and cleanup.

In April 1986, when the Chernobyl

disaster occurred, the EPA was tasked with identifying any impacts on

the United States and keeping the public informed. Administrator Lee

Thomas assembled a cross-agency team, including personnel from the

Nuclear Regulatory Commission, National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration, and the Department of Energy to monitor the situation.

They held press conferences for 10 days. This same year, Congress passed the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, which authorized the EPA to gather data on toxic chemicals and share this information with the public.

The EPA also researched the implications of stratospheric ozone

depletion. Under the leadership of Administrator Lee Thomas, the EPA

joined with several international organizations to perform a risk

assessment of stratospheric ozone, which helped provide motivation for the Montreal Protocol, which was agreed to in August 1987.

In 1988, during his first presidential campaign, George H. W. Bush was vocal about environmental issues. He appointed as his EPA administrator William K. Reilly,

an environmentalist. Under Reilly’s leadership, the EPA implemented

voluntary programs and a cluster rule for multimedia regulation. At the

time, the environment was increasingly being recognized as a regional

issue, which was reflected in 1990 amendment of the Clean Air Act and

new approaches by the agency.

Organization

The EPA is led by an Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. From February 2017 to July 2018, Scott Pruitt served as the 14th Administrator. The current acting administrator is Deputy Administrator Andrew R. Wheeler.

Offices

- Office of the Administrator (OA). As of March 2017 the office consisted of 11 divisions, the Office of Administrative and Executive Services, Office of Children's Health Protection, Office of Civil Rights, Office of Congressional and Intergovernmental Relations, Office of the Executive Secretariat, Office of Homeland Security, Office of Policy, Office of Public Affairs, Office of Public Engagement and Environmental Education, Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization, Science Advisory Board.

- Office of Administration and Resources Management (OARM)

- Office of Air and Radiation (OAR)

- Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention (OCSPP)

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO)

- Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA)

- Office of Environmental Information (OEI)

- Office of General Counsel (OGC)

- Office of Inspector General (OIG)

- Office of International and Tribal Affairs (OITA)

- Office of Research and Development (ORD) which as of March 2017 consisted of the

-

- National Center for Computational Toxicology, National Center for Environmental Assessment, National Center for Environmental Research, National Exposure Research Laboratory, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, National Homeland Security Research Center, National Risk Management Research Laboratory

- Office of Land and Emergency Management (OLEM)

-

- which as of March 2017 consisted of the Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation, Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery, Office of Underground Storage Tanks, Office of Brownfields and Land Revitalization, Office of Emergency Management, Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office.

- Office of Water (OW) which as of March 2017 consisted of the Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water (OGWDW), Office of Science and Technology (OST), Office of Wastewater Management (OWM) and Office of Wetlands, Oceans and Watersheds (OWOW).

Regions

The administrative regions of the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Creating 10 EPA regions was an initiative that came from President Richard Nixon.

Each EPA regional office is responsible within its states for

implementing the Agency's programs, except those programs that have been

specifically delegated to states.

- Region 1: responsible within the states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont (New England).

- Region 2: responsible within the states of New Jersey and New York. It is also responsible for the US territories of Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

- Region 3: responsible within the states of Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

- Region 4: responsible within the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

- Region 5: responsible within the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

- Region 6: responsible within the states of Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas.

- Region 7: responsible within the states of Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska.

- Region 8: responsible within the states of Colorado, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming.

- Region 9: responsible within the states of Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, the territories of Guam and American Samoa, and the Navajo Nation.

- Region 10: responsible within the states of Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington.

Each regional office also implements programs on Indian Tribal lands, except those programs delegated to tribal authorities.

Related legislation

EPA has principal implementation authority for the following federal environmental laws:

- Clean Air Act

- Clean Water Act

- Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act ("Superfund")

- Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act

- Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act

- Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

- Safe Drinking Water Act

- Toxic Substances Control Act.

There are additional laws where EPA has a contributing role or provides assistance to other agencies. Among these laws are:

- Endangered Species Act

- Energy Independence and Security Act

- Energy Policy Act

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

- Food Quality Protection Act

- National Environmental Policy Act

- Oil Pollution Act

- Pollution Prevention Act

Programs

A bulldozer piles boulders in an attempt to prevent lake shore erosion, 1973 (photograph by Paul Sequeira, photojournalist and contributing photographer to the Environmental Protection Agency's DOCUMERICA project in the early 1970s)

It is worth noting that, in looking back in 2013 on the agency he

helped shape from the beginning, Administrator William Ruckelshaus

observed that a danger for EPA was that air, water, waste and other

programs would be unconnected, placed in "silos," a problem that

persists more than 50 years later, albeit less so than at the start.

EPA Safer Choice

The EPA Safer Choice

label, previously known as the Design for the Environment (DfE) label,

helps consumers and commercial buyers identify and select products with

safer chemical ingredients, without sacrificing quality or performance.

When a product has the Safer Choice label, it means that every

intentionally-added ingredient in the product has been evaluated by EPA

scientists. Only the safest possible functional ingredients are allowed

in products with the Safer Choice label.

Safer Detergents Stewardship Initiative

Through the Safer Detergents Stewardship Initiative (SDSI), EPA's Design for the Environment (DfE) recognizes environmental leaders who voluntarily commit to the use of safer surfactants.

Safer surfactants are the ones that break down quickly to non-polluting

compounds and help protect aquatic life in both fresh and salt water. Nonylphenol ethoxylates, commonly referred to as NPEs, are an example of a surfactant class that does not meet the definition of a safer surfactant.

The Design for the Environment, which was renamed to EPA Safer Choice

in 2015, has identified safer alternative surfactants through

partnerships with industry and environmental advocates. These safer

alternatives are comparable in cost and are readily available.

CleanGredients[55] is a source of safer surfactants.

Energy Star

In 1992 the EPA launched the Energy Star

program, a voluntary program that fosters energy efficiency. This

program came out an increased effort to collaborate with industry. At

the start, it motivated major companies to retrofit millions of square

feet of building space with more efficient lighting.

As of 2006, more than 40,000 Energy Star products were available

including major appliances, office equipment, lighting, home

electronics, and more. In addition, the label can also be found on new

homes and commercial and industrial buildings. In 2006, about 12 percent

of new housing in the United States was labeled Energy Star.

The EPA estimates it saved about $14 billion in energy costs in

2006 alone. The Energy Star program has helped spread the use of LED traffic lights, efficient fluorescent lighting, power management systems for office equipment, and low standby energy use.

Smart Growth

EPA's

Smart Growth Program, which began in 1998, is to help communities

improve their development practices and get the type of development they

want. Together with local, state, and national experts, EPA encourages

development strategies that protect human health and the environment,

create economic opportunities, and provide attractive and affordable

neighborhoods for people of all income levels.

Pesticides

EPA regulates pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) (which is much older than the agency) and the Food Quality Protection Act. It assesses, registers, regulates, and regularly reevaluates all pesticides

legally sold in the United States. A few challenges this program faces

are transforming toxicity testing, screening pesticides for endocrine

disruptors, and regulating biotechnology and nanotechnology.

The Land Disposal Restrictions Program

This

program sets treatment requirements for hazardous waste before it may

be disposed of on land. I began issuing treatment methods and levels of

requirements in 1986 and these are continually adapted to new hazardous

wastes and treatment technologies. The stringent requirements it sets

and its emphasis on waste minimization practices encourage businesses to

plan to minimize waste generation and prioritize reuse and recycling.

From the start of the program in 1984 to 2004, the volume of hazardous

waste disposed in landfills had decreased 94% and the volume of

hazardous waste disposed of by underground injection had decreased 70%.

Superfund

In the late 1970s, the need to clean up sites such as Love Canal

that had been highly contaminated by previous hazardous waste disposal

became apparent. However the existing regulatory environment depended on

owners or operators to perform environmental control. While the EPA

attempted to use RCRA’s section 7003 to perform this cleanup, it was

clear a new law was needed. In 1980, Congress passed the Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, nicknamed “Superfund.”

This law enabled the EPA to cast a wider net for responsible parties,

including past or present generators and transporters as well as current

and past owners of the site to find funding. The act also established

some funding and a tax mechanism on certain industries to help fund such

cleanup. The latter was not renewed in the 1990s, which means funding

now comes from general approprations. Today, due to restricted funding,

most cleanup is performed by responsible parties under the oversight of

the EPA and states. As of 2016, more than 1,700 sites had been put on

the cleanup list since the creation of the program. Of these, 370 sites

have been cleaned up and removed from the list, cleanup is underway at

535, cleanup facilities have been constructed at 790 but need to be

operated in the future, and 54 are not yet in cleanup stage.

Brownfields Program

This

program, which was started as a pilot program in the 1990s and signed

into law in 2002, provides grants and tools to local governments for the

assessment, cleanup, and revitalization of brownfields.

As of September 2015, the EPA estimates that program grants have

resulted in 56,442 acres of land readied for reuse and leveraged 116,963

jobs and $24.2 billion to do so. Agency studies also found that

property values around assessed or cleaned-up brownfields have increased

5.1 to 12.8 percent.

Fuel Economy

The testing system was originally developed in 1972 and used driving cycles designed to simulate driving during rush-hour in Los Angeles during that era. Until 1984 the EPA reported the exact fuel economy figures calculated from the test. In 1984, the EPA began adjusting city (aka Urban Dynamometer Driving Schedule or UDDS)

results downward by 10% and highway (aka HighWay Fuel Economy Test or

HWFET) results by 22% to compensate for changes in driving conditions

since 1972, and to better correlate the EPA test results with real-world

driving. In 1996, the EPA proposed updating the Federal Testing

Procedures

to add a new higher-speed test (US06) and an air-conditioner-on test

(SC03) to further improve the correlation of fuel economy and emission

estimates with real-world reports. In December 2006 the updated testing

methodology was finalized to be implemented in model year 2008 vehicles

and set the precedent of a 12-year review cycle for the test procedures.

In February 2005, EPA launched a program called "Your MPG" that

allows drivers to add real-world fuel economy statistics into a database

on the EPA's fuel economy website and compare them with others and with

the original EPA test results.

The EPA conducts fuel economy tests on very few vehicles. "Just

18 of the EPA's 17,000 employees work in the automobile-testing

department in Ann Arbor, Michigan, examining 200 to 250 vehicles a year,

or roughly 15 percent of new models. As to that other 85 percent, the

EPA takes automakers at their word—without any testing-accepting

submitted results as accurate."

Two-thirds of the vehicles the EPA tests themselves are randomly

selected and the remaining third is tested for specific reasons.

Although originally created as a reference point for fossil-fueled vehicles, driving cycles have been used for estimating how many miles an electric vehicle will get on a single charge.

Oil spill prevention program

EPA's

oil spill prevention program includes the Spill Prevention, Control,

and Countermeasure (SPCC) and the Facility Response Plan (FRP) rules.

The SPCC Rule applies to all facilities that store, handle, process,

gather, transfer, refine, distribute, use or consume oil or oil

products. Oil products includes petroleum and non-petroleum oils as well

as: animal fats, oils and greases; fish and marine mammal oils; and

vegetable oils. It mandates a written plan for facilities that store

more than 1,320 gallons of fuel above ground or more than 42,000 gallons

below-ground, and which might discharge to navigable waters (as defined

in the Clean Water Act) or adjoining shorelines. Secondary spill containment is mandated at oil storage facilities and oil release containment is required at oil development sites.

Toxics Release Inventory

The Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) is a resource established by the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act

specifically for the public to learn about toxic chemical releases and

pollution prevention activities reported by industrial and federal

facilities. TRI data support informed decision-making by communities, government agencies, companies, and others. Annually, the agency collects data from more than 20,000 facilities.

The EPA has generated a range of tools to support the use of this

inventory, including interactive maps and online databases such as

ChemView.

WaterSense

WaterSense is an EPA program launched in June 2006 to encourage water efficiency in the United States through the use of a special label on consumer products.

Products include high-efficiency toilets (HETs), bathroom sink faucets

(and accessories), and irrigation equipment. WaterSense is a voluntary

program, with EPA developing specifications for water-efficient

products through a public process and product testing by independent

laboratories.

Underground Storage Tanks Program

EPA regulates underground storage tanks (USTs) containing petroleum and hazardous chemicals under Subtitle I of the Solid Waste Disposal Act.

This program was launched in 1985 and covers about 553,000 active USTs.

Since 1984, 1.8 million USTs have been closed in compliance with

regulations. 38 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico manage UST programs with EPA authorization.

When the program began, EPA had only 90 staff to develop a system to

regulate more than 2 million tanks and work with 750,000 owners and

operators. Administrator Lee Thomas told the program’s new manager, Ron

Brand, that it would have to be done differently that EPA’s traditional

approach. This program therefore behaves differently than other EPA

offices, focusing much more on local operations. It is primarily implemented by states, tribes, and territories.

Today, the program supports the inspection of all federally regulated

tanks, cleans up old and new leaks, minimizes potential leaks, and

encourages sustainable reuse of abandoned gas stations.

Drinking Water

EPA ensures safe drinking water for the public, by setting standards for more than 160,000 public water systems nationwide. EPA oversees states, local governments and water suppliers to enforce the standards under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The program includes regulation of injection wells

in order to protect underground sources of drinking water. Select

readings of amounts of certain contaminants in drinking water,

precipitation, and surface water, in addition to milk and air, are

reported on EPA's Rad Net web site in a section entitled Envirofacts.

Despite mandatory reporting certain readings exceeding EPA MCL levels may be deleted or not included.

In 2013, an EPA draft revision relaxed regulations for radiation

exposure through drinking water, stating that current standards are

impractical to enforce. The EPA recommended that intervention was not

necessary until drinking water was contaminated with radioactive iodine

131 at a concentration of 81,000 picocuries per liter (the limit for

short term exposure set by the International Atomic Energy Agency),

which was 27,000 times the prior EPA limit of 3 picocuries per liter for

long term exposure.

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System

The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program addresses water pollution by regulating point sources

which discharge to US waters. Created in 1972 by the Clean Water Act,

the NPDES permit program authorizes state governments to perform its

many permitting, administrative, and enforcement aspects. As of 2018, EPA has approved 47 states to administer all or portions of the permit program. EPA regional offices manage the program in the remaining areas of the country. The Water Quality Act of 1987 extended NPDES permit coverage to industrial stormwater dischargers and municipal separate storm sewer systems.[78]

In 2016, there were 6,700 major point source NPDES permits in place and

109,000 municipal and industrial point sources with general or

individual permits.

RCRA Corrective Action

This

program is a federal and state cleanup program. Established by RCRA, it

requires that facilities that treat, store, or dispose of hazardous

wastes investigate and clean up hazardous releases at their own expense.

For this purpose, the EPA has developed guidance and policy to assist

facilities. It is largely implemented through permits and orders.

As of 2016, the program has led to the cleanup of 18 million acres of

land, of which facilities were primarily responsible for cleanup costs.

The goal of EPA and states is to complete final remedies by 2020 at

3,779 priority facilities out of 6,000 that need to be cleaned up

according to the program.

Radiation Protection

EPA has the following seven project groups to protect the public from radiation.

- Radioactive Waste Management

- Emergency Preparedness and Response Programs Protective Action Guides And Planning Guidance for Radiological Incidents: EPA developed a manual as guideline for local and state governments to protect the public from a nuclear accident, the 2017 version being a 15-year update.

- EPA's Role in Emergency Response – Special Teams

- Technologically Enhanced Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (TENORM) Program

- Radiation Standards for Air and Drinking Water Programs

- Federal Guidance for Radiation Protection

Tools for Schools

EPA's

Indoor Air Quality Tools for Schools Program helps schools to maintain a

healthy environment and reduce exposures to indoor environmental

contaminants. It helps school personnel identify, solve, and prevent

indoor air quality problems in the school environment. Through the use

of a multi-step management plan and checklists for the entire building,

schools can lower their students' and staff's risk of exposure to asthma

triggers.

Environmental education

The National Environmental Education Act

of 1990 requires EPA to provide national leadership to increase

environmental literacy. EPA established the Office of Environmental

Education to implement this program.

Clean School Bus USA

Clean

School Bus USA is a national partnership to reduce children's exposure

to diesel exhaust by eliminating unnecessary school bus idling,

installing effective emission control systems on newer buses and

replacing the oldest buses in the fleet with newer ones. Its goal is to

reduce both children's exposure to diesel exhaust and the amount of air

pollution created by diesel school buses.

Green Chemistry Program

This program encourages the development of products and processes that follow green chemistry principles. It has recognized more than 100 winning technologies. These reduce the use or creation of hazardous chemicals, save water, and reduce greenhouse gas release.

Section 404 Program

This

permit program regulates the discharge of dredged or fill material into

waters of the United States. Permits are to be denied if they would

cause unacceptable degradation or if an alternative doesn't exist that

does not also have adverse impacts on waters. Permit holders are typically required to restore or create wetlands or other waters to offset losses that can't be avoided.

State Revolving Loan Fund Program

This

program replaced the Construction Grants Program, which was phased out

in 1990. This program distributes grants to states which, along with

matching state funds, are loaned to municipalities for wastewater

infrastructure at below-market interest rates.

These loans are expected to be paid back, creating revolving loan

funds. Through 2014, a total of $36.2 billion in capitalization grants

from the EPA have been provided to the states' revolving funds.

Beach Program

Established by a 2000 amendment to the Clean Water Act,

the Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health (BEACH) Act,

this program was established for specific attention to be paid to the

coastal recreational waters, and required the EPA to develop criteria to

test and monitor waters and notify public users of any concerns.

The program involves states, local beach resource managers, and the

agency in assessing risks of stormwater and wastewater overflows and

enables better sampling, analytical methods, and communication with the

public.

Geographic Programs

The

EPA has also established specific programs for particular water

resources such as the Chesapeake Bay Program, National Estuaries

Program, and Gulf of Mexico Program.

Construction Grants Program (Past)

This

program distributed federal grants for the construction of municipal

wastewater treatment works from 1972 to 1990. While such grants existed

before the passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972, it expanded these

grants dramatically. They were distributed through 1990, when the

program and funding were replaced with the State Revolving Loan Fund

Program.

33/50 Program (Past)

In 1991 under Administrator William Reilly, the EPA implemented its voluntary 33/50 program.

This was designed to encourage, recognize, and celebrate companies that

voluntarily found ways to prevent and reduce pollution in their

operations.

Specifically, it challenged industry to reduce Toxic Release Inventory

emissions of 17 priority chemicals by 33% in one year and 50% in four

years. These results were achieved before the commitment deadlines.

2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program (Past)

Launched

in 2006, this voluntary program worked with eight major companies to

voluntarily reduce their global emissions of certain types of

perfluorinated chemicals by 95% by 2010 and eliminate these emissions by

2015.

Chemical Data Reporting

When the Toxic Substances Control Act

was passed in 1976, it required the EPA to create and maintain a

national inventory of all existing chemicals in U.S. commerce. When the

act was passed, there were more than 60,000 chemicals on the market that

had never been comprehensively cataloged. To do so, the EPA developed

and implemented procedures that have served as a model for Canada,

Japan, and the European Union. For the inventory, the EPA also

established a baseline for new chemicals that the agency should be

notified about before being commercially manufactured. Today, this rule

keeps the EPA updated on volumes, uses, and exposures of around 7,000 of

the highest-volume chemicals via industry reporting.

Environmental Justice

The EPA has been criticized for its lack of progress towards environmental justice. Administrator Christine Todd Whitman was criticized for her changes to President Bill Clinton's Executive Order

12898 during 2001, removing the requirements for government agencies to

take the poor and minority populations into special consideration when

making changes to environmental legislation, and therefore defeating the

spirit of the Executive Order. In a March 2004 report, the inspector general

of the agency concluded that the EPA "has not developed a clear vision

or a comprehensive strategic plan, and has not established values,

goals, expectations, and performance measurements" for environmental

justice in its daily operations. Another report in September 2006 found

the agency still had failed to review the success of its programs,

policies and activities towards environmental justice. Studies have also found that poor and minority populations were underserved by the EPA's Superfund program, and that this situation was worsening.

Barriers to enforcing environmental justice

Many environmental justice issues are local, and therefore difficult

to address by a federal agency, such as the EPA. Without strong media

attention, political interest, or 'crisis' status, local issues are less

likely to be addressed at the federal level compared to larger, well

publicized incidents.

Conflicting political powers in successive administrations: The

White House maintains direct control over the EPA, and its enforcements

are subject to the political agenda of who is in power. Republicans and

Democrats differ in their approaches to environmental justice. While

President Bill Clinton signed the executive order 12898, the Bush

administration did not develop a clear plan or establish goals for

integrating environmental justice into everyday practices, affecting the

motivation for environmental enforcement.

The EPA is responsible for preventing and detecting environmental

crimes, informing the public of environmental enforcement, and setting

and monitoring standards of air pollution, water pollution, hazardous

wastes and chemicals. "It is difficult to construct a specific mission

statement given its wide range of responsibilities."

It is impossible to address every environmental crime adequately or

efficiently if there is no specific mission statement to refer to. The

EPA answers to various groups, competes for resources, and confronts a

wide array of harms to the environment. All of these present challenges,

including a lack of resources, its self-policing policy, and a broadly

defined legislation that creates too much discretion for EPA officers.

The EPA "does not have the authority or resources to address

injustices without an increase in federal mandates" requiring private

industries to consider the environmental ramifications of their

activities.

Research vessel, 2004–2013

OSV Bold docked at Port Canaveral, Florida

In March 2004, the U.S. Navy transferred USNS Bold (T-AGOS-12), a Stalwart class ocean surveillance ship, to the EPA. The ship had been used in anti-submarine operations during the Cold War,

was equipped with sidescan sonar, underwater video, water and sediment

sampling instruments used in study of ocean and coastline. One of the

major missions of the Bold was to monitor for ecological impact sites where materials were dumped from dredging operations in U.S. ports. In 2013, the General Services Administration sold the Bold to Seattle Central Community College

(SCCC), which demonstrated in a competition that they would put it to

the highest and best purpose, at a nominal cost of $5,000.

Advance identification

Advance

identification, or ADID, is a planning process used by the EPA to

identify wetlands and other bodies of water and their respective

suitability for the discharge of dredged and fill material. The EPA

conducts the process in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and local states or Native American Tribes. As of February 1993, 38 ADID projects had been completed and 33 were ongoing.

Freedom of Information Act processing performance

In the latest Center for Effective Government analysis of 15 federal agencies which receive the most Freedom of Information Act

FOIA requests, published in 2015 (using 2012 and 2013 data, the most

recent years available), the EPA earned a D by scoring 67 out of a

possible 100 points, i.e. did not earn a satisfactory overall grade.

Controversies (1983–present)

EPA headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Fiscal mismanagement, 1983

In 1982 Congress charged that the EPA had mishandled the $1.6 billion program to clean up hazardous waste dumps Superfund and demanded records from EPA director Anne M. Gorsuch. She refused and became the first agency director in U.S. history to be cited for contempt of Congress.

The EPA turned the documents over to Congress several months later,

after the White House abandoned its court claim that the documents could

not be subpoenaed by Congress because they were covered by executive privilege. At that point, Gorsuch resigned her post, citing pressures caused by the media and the congressional investigation. Critics charged that the EPA was in a shambles at that time.

When Lee Thomas came to the agency in 1983 as Acting Assistant

Administrator of the Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response,

shortly before Gorsuch's resignation, six congressional committees were

investigating the Superfund program. There were also two FBI agents

performing an investigation for the Justice Department into possible

destruction of documents.

Gorsuch, appointed by Ronald Reagan, resigned under fire in 1983. Gorsuch based her administration of the EPA on the New Federalism approach of downsizing federal agencies by delegating their functions and services to the individual states.

She believed that the EPA was over-regulating business and that the

agency was too large and not cost-effective. During her 22 months as

agency head, she cut the budget of the EPA by 22%, reduced the number of

cases filed against polluters, relaxed Clean Air Act regulations, and

facilitated the spraying of restricted-use pesticides. She cut the total

number of agency employees, and hired staff from the industries they

were supposed to be regulating. Environmentalists contended that her policies were designed to placate polluters, and accused her of trying to dismantle the agency.

TSCA and confidential business information, 1994 (or earlier)–present

TSCA

enables the EPA to require industry to conduct testing of chemicals,

but the agency must balance this with obligations to provide information

to the public and ensure the protection of trade secrets and

confidential business information (the legal term for proprietary

information). Arising issues and problems from these overlapping

obligations have been the subject of multiple critical reports by the Government Accountability Office.

How much information the agency should have access to from industry,

how much it should keep confidential, and how much it should reveal to

the public is still contested. For example, according to TSCA, state

officials are not allowed access to confidential business information

collected by the EPA.

Political pressure and scientific integrity, 2001–present

In April 2008, the Union of Concerned Scientists

said that more than half of the nearly 1,600 EPA staff scientists who

responded online to a detailed questionnaire reported they had

experienced incidents of political interference in their work. The

survey included chemists, toxicologists, engineers, geologists and

experts in other fields of science. About 40% of the scientists reported

that the interference had been more prevalent in the last five years

than in previous years. The highest number of complaints came from

scientists who were involved in determining the risks of cancer by

chemicals used in food and other aspects of everyday life.

EPA research has also been suppressed by career managers.

Supervisors at EPA's National Center for Environmental Assessment

required several paragraphs to be deleted from a peer-reviewed journal

article about EPA's integrated risk information system,

which led two co-authors to have their names removed from the

publication, and the corresponding author, Ching-Hung Hsu, to leave EPA

"because of the draconian restrictions placed on publishing". EPA subjects employees who author scientific papers to prior restraint, even if those papers are written on personal time.

EPA employees have reported difficulty in conducting and reporting the results of studies on hydraulic fracturing due to industry and governmental pressure, and are concerned about the censorship of environmental reports.

In 2015, the Government Accountability Office

stated that the EPA violated federal law with covert propaganda on

their social media platforms. The social media messaging that was used

promoted materials supporting the Waters of the United States rule, including materials that were designed to oppose legislative efforts to limit or block the rule.

In February 2017, U.S. Representative Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.) sponsored H.R. 861, a bill

to abolish the EPA by 2018. According to Gaetz, "The American people

are drowning in rules and regulation promulgated by unelected

bureaucrats. And the Environmental Protection Agency has become an

extraordinary offender." The bill was co-sponsored by Thomas Massie (R-Ky.), Steven Palazzo (R-Ms.) and Barry Loudermilk (R-Ga.).

Fuel economy, 2005–2010

In

July 2005, an EPA report showing that auto companies were using

loopholes to produce less fuel-efficient cars was delayed. The report

was supposed to be released the day before a controversial energy bill

was passed and would have provided backup for those opposed to it, but

the EPA delayed its release at the last minute.

In 2007, the state of California sued the EPA for its refusal to

allow California and 16 other states to raise fuel economy standards for

new cars. EPA administrator Stephen L. Johnson

claimed that the EPA was working on its own standards, but the move has

been widely considered an attempt to shield the auto industry from

environmental regulation by setting lower standards at the federal

level, which would then preempt state laws. California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, along with governors from 13 other states, stated that the EPA's actions ignored federal law, and that existing California standards (adopted by many states in addition to California) were almost twice as effective as the proposed federal standards. It was reported that Stephen Johnson ignored his own staff in making this decision.

After the federal government had bailed out General Motors and Chrysler in the Automotive industry crisis of 2008–2010, the 2010 Chevrolet Equinox was released with an EPA fuel economy rating abnormally higher than its competitors. Independent road tests[131][132][133][134]

found that the vehicle did not out-perform its competitors, which had

much lower fuel economy ratings. Later road tests found better, but

inconclusive, results.

Mercury emissions, 2005

In

March 2005, nine states (California, New York, New Jersey, New

Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut, New Mexico and Vermont)

sued the EPA. The EPA's Inspector General had determined that the EPA's regulation of mercury emissions did not follow the Clean Air Act, and that the regulations were influenced by top political appointees. The EPA had suppressed a study it commissioned by Harvard University which contradicted its position on mercury controls.

The suit alleged that the EPA's rule exempting coal-fired power plants

from "maximum available control technology" was illegal, and

additionally charged that the EPA's system of cap-and-trade

to lower average mercury levels would allow power plants to forego

reducing mercury emissions, which they objected would lead to dangerous

local hotspots of mercury contamination even if average levels declined.

Several states also began to enact their own mercury emission

regulations. Illinois's proposed rule would have reduced mercury

emissions from power plants by an average of 90% by 2009.

In 2008—by which point a total of fourteen states had joined the

suit—the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that

the EPA regulations violated the Clean Air Act.

In response, EPA announced plans to propose such standards to

replace the vacated Clean Air Mercury Rule, and did so on March 16,

2011.

Climate change, 2007–2017

In December 2007, EPA Administrator Stephen L. Johnson approved a

draft of a document that declared that climate change imperiled the

public welfare—a decision that would trigger the first national

mandatory global-warming regulations. Associate Deputy Administrator

Jason Burnett e-mailed the draft to the White House. White House

aides—who had long resisted mandatory regulations as a way to address

climate change—knew the gist of what Johnson's finding would be, Burnett

said. They also knew that once they opened the attachment, it would

become a public record, making it controversial and difficult to

rescind. So they did not open it; rather, they called Johnson and asked

him to take back the draft. Johnson rescinded the draft; in July 2008,

he issued a new version which did not state that global warming was danger to public welfare. Burnett resigned in protest.

A $3 million mapping study on sea level rise

was suppressed by EPA management during both the Bush and Obama

Administrations, and managers changed a key interagency report to

reflect the removal of the maps.

On April 28, 2017, multiple climate change subdomains at EPA.gov

began redirecting to a notice stating "this page is being updated."

The EPA issued a statement announcing the overhaul of its website to

"reflect the agency's new direction under President Donald Trump and

Administrator Scott Pruitt."

The removed EPA climate change domains included extensive information

on the EPA's work to mitigate climate change, as well as details of data

collection efforts and indicators for climate change.

Gold King Mine waste water spill, 2015

In August 2015, the 2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill occurred when EPA contractors examined the level of pollutants such as lead and arsenic in a Colorado mine, and accidentally released over three million gallons of waste water into Cement Creek and the Animas River.

Collusion with Monsanto chemical company

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a branch of the World Health Organization, cited research linking glyphosate, an ingredient of the weed killer Roundup manufactured by the chemical company Monsanto, to non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

In March 2017, the presiding judge in a litigation brought about by

people who claim to have developed glyphosate-related non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma opened Monsanto emails and other documents related to the case,

including email exchanges between the company and federal regulators.

According to an article in the New York Times, the "records

suggested that Monsanto had ghostwritten research that was later

attributed to academics and indicated that a senior official at the

Environmental Protection Agency had worked to quash a review of

Roundup’s main ingredient, glyphosate, that was to have been conducted

by the United States Department of Health and Human Services." The

records show that Monsanto was able to prepare "a public relations

assault" on the finding after they were alerted to the determination by

Jess Rowland, the head of the EPA’s cancer assessment review committee

at that time, months in advance. Emails also showed that Rowland "had

promised to beat back an effort by the Department of Health and Human Services to conduct its own review."

Chief Scott Pruitt, 2017

On February 17, 2017, Scott Pruitt was selected Administrator of the EPA by president Donald Trump.

This was a seemingly controversial move, as Pruitt had spent most of

his career countering environmental policy. He did not have previous

experience in the field and had received financial support from the

fossil fuel industry.

Pruitt resigned from the position on July 5, 2018, citing "unrelenting attacks" due to ongoing ethics controversies.