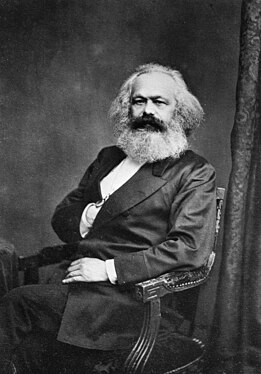

19th-century German intellectual Karl Marx (1818–1883) identified and described four types of Entfremdung (social alienation) that afflict the worker under capitalism.

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the estrangement (Entfremdung) of people from aspects of their Gattungswesen ("species-essence") as a consequence of living in a society of stratified social classes.

The alienation from the self is a consequence of being a mechanistic

part of a social class, the condition of which estranges a person from

their humanity.

The theoretical basis of alienation within the capitalist mode of production

is that the worker invariably loses the ability to determine life and

destiny when deprived of the right to think (conceive) of themselves as

the director of their own actions; to determine the character of said

actions; to define relationships with other people; and to own those

items of value from goods and services, produced by their own labor.

Although the worker is an autonomous, self-realized human being, as an

economic entity this worker is directed to goals and diverted to

activities that are dictated by the bourgeoisie—who own the means of production—in order to extract from the worker the maximum amount of surplus value in the course of business competition among industrialists.

In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1932), Karl Marx expressed the Entfremdung theory—of estrangement from the self. Philosophically, the theory of Entfremdung relies upon The Essence of Christianity (1841) by Ludwig Feuerbach which states that the idea of a supernatural god has alienated the natural characteristics of the human being. Moreover, Max Stirner extended Feuerbach's analysis in The Ego and its Own

(1845) that even the idea of "humanity" is an alienating concept for

individuals to intellectually consider in its full philosophic

implication. Marx and Friedrich Engels responded to these philosophic propositions in The German Ideology (1845).

Types of alienation

In a capitalist society, the worker's alienation from their humanity

occurs because the worker can only express labour—a fundamental social

aspect of personal individuality—through a private system of industrial

production in which each worker is an instrument, a thing and not a

person. In the "Comment on James Mill" (1844), Marx explained alienation

thus:

Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. (ii) In your enjoyment, or use, of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man's essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man's essential nature [...] Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.

In the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (1932), Marx identified four types of alienation that occur to the worker laboring under a capitalist system of industrial production.

Alienation of the worker from their product

The

design of the product and how it is produced are determined, not by the

producers who make it (the workers), nor by the consumers of the

product (the buyers), but by the capitalist class who besides accommodating the worker's manual labor also accommodate the intellectual labor of the engineer and the industrial designer who create the product in order to shape the taste of the consumer to buy the goods and services at a price that yields a maximal profit. Aside from the workers having no control over the design-and-production protocol, alienation (Entfremdung) broadly describes the conversion of labor (work as an activity), which is performed to generate a use value (the product), into a commodity, which—like products—can be assigned an exchange value.

That is, the capitalist gains control of the manual and intellectual

workers and the benefits of their labour, with a system of industrial

production that converts said labor into concrete products (goods and

services) that benefit the consumer. Moreover, the capitalist production

system also reifies

labour into the "concrete" concept of "work" (a job), for which the

worker is paid wages—at the lowest-possible rate—that maintain a maximum

rate of return on the capitalist's investment capital; this is an aspect of exploitation.

Furthermore, with such a reified system of industrial production, the

profit (exchange value) generated by the sale of the goods and services

(products) that could be paid to the workers is instead paid to the

capitalist classes: the functional capitalist, who manages the means of

production; and the rentier capitalist, who owns the means of production.

In the capitalist mode of production, the manual labor of the employed carpenter yields wages, but not profits or losses

In

the capitalist mode of production, the intellectual labor of the

employed engineer yields a salary, but not profits or losses

Strikers confronted by soldiers during the 1912 textile factory strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, United States called when owners reduced wages after a state law reduced the work week from 56 to 54 hours

Alienation of the worker from the act of production

In the capitalist mode of production,

the generation of products (goods and services) is accomplished with an

endless sequence of discrete, repetitive motions that offer the worker

little psychological satisfaction for "a job well done". By means of commodification, the labor power of the worker is reduced to wages (an exchange value); the psychological estrangement (Entfremdung)

of the worker results from the unmediated relation between his

productive labor and the wages paid to him for the labor. The worker is

alienated from the means of production via two forms; wage compulsion

and the imposed production content. The worker is bound to unwanted

labor as a means of survival, labour is not "voluntary but coerced"

(forced labor). The worker is only able to reject wage compulsion at the

expense of their life and that of their family. The distribution of private property

in the hands of wealth owners, combined with government enforced taxes

compel workers to labor. In a capitalist world, our means of survival is

based on monetary exchange, therefore we have no other choice than to

sell our labor power and consequently be bound to the demands of the

capitalist. The worker "[d]oes not feel content but unhappy, does not

develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and

ruins his mind. The worker therefore only feels himself outside his

work, and in his work feels outside himself"; "[l]abor is external to

the worker" (p. 74), it is not a part of their essential being. During

work, the worker is miserable, unhappy and drained of their energy, work

"mortifies his body and ruins his mind". The production content,

direction and form are imposed by the capitalist. The worker is being

controlled and told what to do since they do not own the means of

production they have no say in production, "labor is external to the

worker, i.e. it does not belong to his essential being (p. 74). A

person's mind should be free and conscious, instead it is controlled and

directed by the capitalist, "the external character of labor for the

worker appears in the fact that it is not his own but someone else's,

that it does not belong to him, that in it he belongs, not to himself,

but to another" (p. 74). This means he cannot freely and spontaneously

create according to his own directive as labor's form and direction

belong to someone else.

Alienation of the worker from their Gattungswesen (species-essence)

The Gattungswesen

(species-essence), human nature of individuals is not discrete

(separate and apart) from their activity as a worker and as such

species-essence also comprises all of innate human potential as a

person. Conceptually, in the term "species-essence" the word "species"

describes the intrinsic human mental essence that is characterized by a

"plurality of interests" and "psychological dynamism", whereby every

individual has the desire and the tendency to engage in the many

activities that promote mutual human survival and psychological

well-being, by means of emotional connections with other people, with

society. The psychic value of a human consists in being able to conceive

(think) of the ends of their actions as purposeful ideas, which are

distinct from the actions required to realize a given idea. That is,

humans are able to objectify their intentions by means of an idea of

themselves as "the subject" and an idea of the thing that they produce,

"the object". Conversely, unlike a human being an animal does not

objectify itself as "the subject" nor its products as ideas, "the

object", because an animal engages in directly self-sustaining actions

that have neither a future intention, nor a conscious intention. Whereas a person's Gattungswesen

(human nature) does not exist independently of specific, historically

conditioned activities, the essential nature of a human being is

actualized when an individual—within their given historical

circumstance—is free to subordinate their will to the internal demands

they have imposed upon themselves by their imagination and not the

external demands imposed upon individuals by other people.

Relations of production

Whatever the character of a person's consciousness (will and imagination),

societal existence is conditioned by their relationships with the

people and things that facilitate survival, which is fundamentally

dependent upon co-operation with others, thus, a person's consciousness

is determined inter-subjectively (collectively), not subjectively

(individually), because humans are a social animal. In the course of

history, to ensure individual survival societies have organized

themselves into groups who have different, basic relationships to the means of production.

One societal group (class) owned and controlled the means of production

while another societal class worked the means of production and in the relations of production of that status quo

the goal of the owner-class was to economically benefit as much as

possible from the labour of the working class. In the course of economic

development when a new type of economy displaced an old type of

economy—agrarian feudalism superseded by mercantilism, in turn superseded by the Industrial Revolution—the rearranged economic order of the social classes favored the social class who controlled the technologies

(the means of production) that made possible the change in the

relations of production. Likewise, there occurred a corresponding

rearrangement of the human nature (Gattungswesen) and the system of values of the owner-class and of the working-class, which allowed each group of people to accept and to function in the rearranged status quo of production-relations.

Despite the ideological promise of industrialization—that the

mechanization of industrial production would raise the mass of the

workers from a brutish life of subsistence existence to honorable

work—the division of labor inherent to the capitalist mode of

production thwarted the human nature (Gattungswesen) of the

worker and so rendered each individual into a mechanistic part of an

industrialized system of production, from being a person capable of

defining their value through direct, purposeful activity. Moreover, the

near-total mechanization and automation of the industrial production

system would allow the (newly) dominant bourgeois

capitalist social class to exploit the working class to the degree that

the value obtained from their labor would diminish the ability of the

worker to materially survive. Hence, when the proletarian working-class

become a sufficiently developed political force, they will effect a

revolution and re-orient the relations of production to the means of production—from a capitalist mode of production to a communist mode of production. In the resultant communist society,

the fundamental relation of the workers to the means of production

would be equal and non-conflictual because there would be no artificial

distinctions about the value of a worker's labor; the worker's humanity

(species-essence) thus respected, men and women would not become

alienated.

In the communist socio-economic organization, the relations of production would operate the mode of production and employ each worker according to their abilities and benefit each worker according to their needs.

Hence, each worker could direct their labor to productive work

suitable to their own innate abilities, rather than be forced into a

narrowly defined, minimal-wage

"job" meant to extract maximal profit from individual labor as

determined by and dictated under the capitalist mode of production. In

the classless, collectively-managed communist society, the exchange of

value between the objectified

productive labor of one worker and the consumption benefit derived

from that production will not be determined by or directed to the narrow

interests of a bourgeois capitalist class, but instead will be directed

to meet the needs of each producer and consumer. Although production

will be differentiated by the degree of each worker's abilities, the

purpose of the communist system of industrial production will be

determined by the collective requirements of society, not by the

profit-oriented demands of a capitalist social class who live at the

expense of the greater society. Under the collective ownership

of the means of production, the relation of each worker to the mode of

production will be identical and will assume the character that

corresponds to the universal interests of the communist society. The

direct distribution of the fruits of the labour of each worker to

fulfill the interests of the working class—and thus to an individuals

own interest and benefit—will constitute an un-alienated state of labor

conditions, which restores to the worker the fullest exercise and

determination of their human nature.

Alienation of the worker from other workers

Capitalism reduces the labour of the worker to a commercial commodity

that can be traded in the competitive labor market, rather than as a

constructive socio-economic activity that is part of the collective

common effort performed for personal survival and the betterment of

society. In a capitalist economy, the businesses who own the means of production establish a competitive labor market meant to extract from the worker as much labour (value) as possible in the form of capital. The capitalist economy's arrangement of the relations of production

provokes social conflict by pitting worker against worker in a

competition for "higher wages", thereby alienating them from their

mutual economic interests; the effect is a false consciousness, which is a form of ideological control exercised by the capitalist bourgeoisie through its cultural hegemony. Furthermore, in the capitalist mode of production the philosophic collusion of religion in justifying the relations of production facilitates the realization and then worsens the alienation (Entfremdung) of the worker from their humanity; it is a socio-economic role independent of religion being "the opiate of the masses".

Philosophical significance

Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) postulated the idealism that Marx countered with dialectical materialism

Philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872) analysed religion from a psychological perspective in The Essence of Christianity (1841) and according to him divinity is humanity's projection of their human nature

Influences: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach

In Marxist theory, Entfremdung (alienation) is a foundational proposition about man's progress towards self-actualisation. In the Oxford Companion to Philosophy (2005), Ted Honderich described the influences of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Ludwig Feuerbach upon Karl Marx:

For Hegel, the unhappy consciousness is divided against itself, separated from its "essence", which it has placed in a "beyond".

As used by the philosophers Hegel and Marx, the reflexive German verbs entäussern ("to divest one's self of") and entfremden

("to become estranged") indicate that the term "alienation" denotes

self-alienation: to be estranged from one's essential nature.

Therefore, alienation is a lack of self-worth, the absence of meaning

in one's life, consequent to being coerced to lead a life without

opportunity for self-fulfillment, without the opportunity to become

actualized, to become one's self.

In The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), Hegel described the stages in the development of the human Geist

("Spirit"), by which men and women progress from ignorance to

knowledge, of the self and of the world. Developing Hegel's human-spirit

proposition, Marx said that those poles of idealism—"spiritual ignorance" and "self-understanding"—are replaced with material categories, whereby "spiritual ignorance" becomes "alienation" and "self-understanding" becomes man's realisation of his Gattungswesen (species-essence).

Entfremdung and the theory of history

In Part I: "Feuerbach – Opposition of the Materialist and Idealist Outlook" of The German Ideology (1846), Karl Marx said the following:

Things have now come to such a pass that the individuals must appropriate the existing totality of productive forces, not only to achieve self-activity, but also, merely, to safeguard their very existence.

That humans psychologically require the life activities that lead to their self-actualization as persons remains a consideration of secondary historical relevance because the capitalist mode of production eventually will exploit and impoverish the proletariat until compelling them to social revolution for survival. Yet, social alienation remains a practical concern, especially among the contemporary philosophers of Marxist humanism. In The Marxist-Humanist Theory of State-Capitalism (1992), Raya Dunayevskaya

discussed and described the existence of the desire for self-activity

and self-actualisation among wage-labour workers struggling to achieve

the elementary goals of material life in a capitalist economy.

Entfremdung and social class

In Chapter 4 of The Holy Family (1845), Marx said that capitalists and proletarians are equally alienated, but that each social class experiences alienation in a different form:

The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-estrangement. But the former class feels at ease and strengthened in this self-estrangement, it recognizes estrangement as its own power, and has in it the semblance of a human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated, this means that they cease to exist in estrangement; it sees in it its own powerlessness and in the reality of an inhuman existence. It is, to use an expression of Hegel, in its abasement, the indignation at that abasement, an indignation to which it is necessarily driven by the contradiction between its human nature and its condition of life, which is the outright, resolute and comprehensive negation of that nature. Within this antithesis, the private property-owner is therefore the conservative side, and the proletarian the destructive side. From the former arises the action of preserving the antithesis, from the latter the action of annihilating it.

Criticism

In discussion of "random materialism" (matérialisme aléatoire), the French philosopher Louis Althusser criticized such a teleological (goal-oriented) interpretation of Marx's theory of alienation because it rendered the proletariat as the subject of history; an interpretation tainted with the Hegelian idealism of the "philosophy of the subject", which he criticized as the "bourgeois ideology of philosophy" (see History and Class Consciousness [1923] by György Lukács).