A jar made of soda-lime

glass. Although transparent in thin sections, the glass is

greenish-blue in thick sections from impurities. Bubbles remained

trapped in the glass as it cooled from a liquid, through the glass

transition, becoming a non-crystalline solid.

The joining of two tubes made of lead glass during glass welding.

Glass is a non-crystalline, amorphous solid that is often transparent and has widespread practical, technological, and decorative usage in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optoelectronics.

The most familiar, and historically the oldest, types of manufactured

glass are "silicate glasses" based on the chemical compound silica (silicon dioxide, or quartz), the primary constituent of sand. The term glass,

in popular usage, is often used to refer only to this type of material,

which is familiar from use as window glass and in glass bottles. Of the

many silica-based glasses that exist, ordinary glazing and container

glass is formed from a specific type called soda-lime glass, composed of approximately 75% silicon dioxide (SiO2), sodium oxide (Na2O) from sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), calcium oxide (CaO), also called lime, and several minor additives.

Many applications of silicate glasses derive from their optical transparency, giving rise to their primary use as window panes. Glass will transmit, reflect and refract light; these qualities can be enhanced by cutting and polishing to make optical lenses, prisms, fine glassware, and optical fibers

for high speed data transmission by light. Glass can be colored by

adding metallic salts, and can also be painted and printed with vitreous enamels. These qualities have led to the extensive use of glass in the manufacture of art objects and in particular, stained glass windows.

Although brittle, silicate glass is extremely durable, and many

examples of glass fragments exist from early glass-making cultures.

Because glass can be formed or molded into any shape, it has been

traditionally used for vessels: bowls, vases, bottles, jars and drinking glasses. In its most solid forms it has also been used for paperweights, marbles, and beads. When extruded as glass fiber and matted as glass wool

in a way to trap air, it becomes a thermal insulating material, and

when these glass fibers are embedded into an organic polymer plastic, they are a key structural reinforcement part of the composite material fiberglass.

Some objects historically were so commonly made of silicate glass that

they are simply called by the name of the material, such as drinking

glasses and eyeglasses.

Scientifically, the term "glass" is often defined in a broader

sense, encompassing every solid that possesses a non-crystalline (that

is, amorphous) structure at the atomic scale and that exhibits a glass transition when heated towards the liquid state. Porcelains and many polymer thermoplastics

familiar from everyday use are glasses. These sorts of glasses can be

made of quite different kinds of materials than silica: metallic alloys, ionic melts, aqueous solutions, molecular liquids, and polymers. For many applications, like glass bottles or eyewear, polymer glasses (acrylic glass, polycarbonate or polyethylene terephthalate) are a lighter alternative than traditional glass.

Silicate glass

Ingredients

Silicon dioxide (SiO2) is a common fundamental constituent of glass. In nature, vitrification of quartz occurs when lightning strikes sand, forming hollow, branching root-like structures called fulgurites.

Fused quartz is a glass made from chemically-pure silica. It has excellent resistance to thermal shock, being able to survive immersion in water while red hot. However, its high melting temperature (1723 °C) and viscosity make it difficult to work with. Normally, other substances are added to simplify processing. One is sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, "soda"), which lowers the glass-transition temperature. The soda makes the glass water-soluble, which is usually undesirable, so lime (CaO, calcium oxide, generally obtained from limestone), some magnesium oxide (MgO) and aluminium oxide (Al2O3)

are added to provide for a better chemical durability. The resulting

glass contains about 70 to 74% silica by weight and is called a soda-lime glass. Soda-lime glasses account for about 90% of manufactured glass.

Most common glass contains other ingredients to change its properties. Lead glass or flint glass is more "brilliant" because the increased refractive index causes noticeably more specular reflection and increased optical dispersion. Adding barium also increases the refractive index. Thorium oxide gives glass a high refractive index and low dispersion and was formerly used in producing high-quality lenses, but due to its radioactivity has been replaced by lanthanum oxide in modern eyeglasses. Iron can be incorporated into glass to absorb infrared radiation, for example in heat-absorbing filters for movie projectors, while cerium(IV) oxide can be used for glass that absorbs ultraviolet wavelengths.

The following is a list of the more common types of silicate glasses and their ingredients, properties, and applications:

- Fused quartz, also called fused-silica glass, vitreous-silica glass: silica (SiO2) in vitreous, or glass, form (i.e., its molecules are disordered and random, without crystalline structure). It has very low thermal expansion, is very hard, and resists high temperatures (1000–1500 °C). It is also the most resistant against weathering (caused in other glasses by alkali ions leaching out of the glass, while staining it). Fused quartz is used for high-temperature applications such as furnace tubes, lighting tubes, melting crucibles, etc.

- Soda-lime-silica glass, window glass: silica + sodium oxide (Na2O) + lime (CaO) + magnesia (MgO) + alumina (Al2O3). Is transparent, easily formed and most suitable for window glass (see flat glass). It has a high thermal expansion and poor resistance to heat (500–600 °C). It is used for windows, some low-temperature incandescent light bulbs, and tableware. Container glass is a soda-lime glass that is a slight variation on flat glass, which uses more alumina and calcium, and less sodium and magnesium, which are more water-soluble. This makes it less susceptible to water erosion.

- Sodium borosilicate glass, Pyrex: silica + boron trioxide (B2O3) + soda (Na2O) + alumina (Al2O3). Stands heat expansion much better than window glass. Used for chemical glassware, cooking glass, car head lamps, etc. Borosilicate glasses (e.g. Pyrex, Duran) have as main constituents silica and boron trioxide. They have fairly low coefficients of thermal expansion (7740 Pyrex CTE is 3.25×10−6/°C as compared to about 9×10−6/°C for a typical soda-lime glass), making them more dimensionally stable. The lower coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) also makes them less subject to stress caused by thermal expansion, thus less vulnerable to cracking from thermal shock. They are commonly used for reagent bottles, optical components and household cookware.

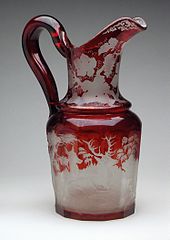

- Lead-oxide glass, crystal glass, lead glass: silica + lead oxide (PbO) + potassium oxide (K2O) + soda (Na2O) + zinc oxide (ZnO) + alumina. Because of its high density (resulting in a high electron density), it has a high refractive index, making the look of glassware more brilliant (called "crystal", though of course it is a glass and not a crystal). It also has a high elasticity, making glassware "ring". It is also more workable in the factory, but cannot stand heating very well. This kind of glass is also more fragile than other glasses and is easier to cut.

- Aluminosilicate glass: silica + alumina + lime + magnesia + barium oxide (BaO) + boric oxide (B2O3). Extensively used for fiberglass, used for making glass-reinforced plastics (boats, fishing rods, etc.) and for halogen bulb glass. Aluminosilicate glasses are also resistant to weathering and water erosion.

- Germanium-oxide glass: alumina + germanium dioxide (GeO2). Extremely clear glass, used for fiber-optic waveguides in communication networks. Light loses only 5% of its intensity through 1 km of glass fiber.

Another common glass ingredient is crushed alkali glass or 'cullet' ready for recycled glass.

The recycled glass saves on raw materials and energy. Impurities in the

cullet can lead to product and equipment failure. Fining agents such as

sodium sulfate, sodium chloride, or antimony oxide may be added to reduce the number of air bubbles in the glass mixture. Glass batch calculation is the method by which the correct raw material mixture is determined to achieve the desired glass composition.

- Quartz sand (silica) is the main raw material in commercial glass production

- Trinitite, a glass made by the Trinity nuclear-weapon test

- Lead glass a glass made by adding lead oxide to glass

Physical properties

Optical properties

Glass is in widespread use largely due to the production of glass

compositions that are transparent to visible light. In contrast, polycrystalline materials do not generally transmit visible light. The individual crystallites may be transparent, but their facets (grain boundaries) reflect or scatter light resulting in diffuse reflection.

Glass does not contain the internal subdivisions associated with grain

boundaries in polycrystals and hence does not scatter light in the same

manner as a polycrystalline material. The surface of a glass is often

smooth since during glass formation the molecules of the supercooled

liquid are not forced to dispose in rigid crystal geometries and can

follow surface tension,

which imposes a microscopically smooth surface. These properties, which

give glass its clearness, can be retained even if glass is partially

light-absorbing, i.e., colored.

Glass has the ability to refract, reflect, and transmit light following geometrical optics, without scattering it (due to the absence of grain boundaries). It is used in the manufacture of lenses and windows. Common glass has a refraction index around 1.5. This may be modified by adding low-density materials such as boron, which lowers the index of refraction (see crown glass), or increased (to as much as 1.8) with high-density materials such as (classically) lead oxide (see flint glass and lead glass), or in modern uses, less toxic oxides of zirconium, titanium, or barium.

These high-index glasses (inaccurately known as "crystal" when used in

glass vessels) cause more chromatic dispersion of light, and are prized

for their diamond-like optical properties.

According to Fresnel equations, the reflectivity of a sheet of glass is about 4% per surface (at normal incidence in air), and the transmissivity of one element (two surfaces) is about 90%. Glass with high germanium oxide content also finds application in optoelectronics—e.g., for light-transmitting optical fibers.

- Simple optical device: the magnifying glass

- Strand of optical glass fiber

Other properties

In the process of manufacture, silicate glass can be poured, formed,

extruded and molded into forms ranging from flat sheets to highly

intricate shapes. The finished product is brittle and will fracture, unless laminated or specially treated, but is extremely durable under most conditions. It erodes very slowly and can mostly withstand the action of water. It is mostly resistant to chemical attack, does not react with foods, and is an ideal material for the manufacture of containers for foodstuffs and most chemicals. Glass is also a fairly inert substance.

Corrosion

Although glass is generally corrosion-resistant and more corrosion resistant than other materials, it still can be corroded. The materials that make up a particular glass composition have an effect on how quickly the glass corrodes. A glass containing a high proportion of alkalis or alkali earths is less corrosion-resistant than other kinds of glasses.

Glass flakes have applications as anti-corrosive coating.

Strength

Glass typically has a tensile strength of 7 megapascals (1,000 psi),

however theoretically it can have a strength of 17 gigapascals

(2,500,000 psi) due to glass's strong chemical bonds. Several factors

such as imperfections like scratches and bubbles and the glass's chemical composition impact the tensile strength of glass. Several processes such as toughening can increase the strength of glass.

Contemporary production

Following the glass batch preparation and mixing, the raw materials are transported to the furnace. Soda-lime glass for mass production is melted in gas fired units. Smaller scale furnaces for specialty glasses include electric melters, pot furnaces, and day tanks.

After melting, homogenization and refining (removal of bubbles), the glass is formed. Flat glass for windows and similar applications is formed by the float glass process, developed between 1953 and 1957 by Sir Alastair Pilkington

and Kenneth Bickerstaff of the UK's Pilkington Brothers, who created a

continuous ribbon of glass using a molten tin bath on which the molten

glass flows unhindered under the influence of gravity. The top surface

of the glass is subjected to nitrogen under pressure to obtain a

polished finish.

Container glass for common bottles and jars is formed by blowing and pressing methods.

This glass is often slightly modified chemically (with more alumina and

calcium oxide) for greater water resistance.

Once the desired form is obtained, glass is usually annealed for the removal of stresses and to increase the glass's hardness and durability.

Surface treatments, coatings or lamination may follow to improve the chemical durability (glass container coatings, glass container internal treatment), strength (toughened glass, bulletproof glass, windshields), or optical properties (insulated glazing, anti-reflective coating).

Color

Some of the many color possibilities of glass

Color in glass may be obtained by addition of electrically charged ions (or color centers) that are homogeneously distributed, and by precipitation of finely dispersed particles (such as in photochromic glasses).

Ordinary soda-lime glass appears colorless to the naked eye when it is thin, although iron(II) oxide (FeO) impurities of up to 0.1 wt% produce a green tint, which can be viewed in thick pieces or with the aid of scientific instruments. Further FeO and chromium(III) oxide (Cr2O3) additions may be used for the production of green bottles. Sulfur, together with carbon and iron salts, is used to form iron polysulfides and produce amber glass ranging from yellowish to almost black. A glass melt can also acquire an amber color from a reducing combustion atmosphere. Manganese dioxide can be added in small amounts to remove the green tint given by iron(II) oxide. Art glass and studio glass

pieces are colored using closely guarded recipes that involve specific

combinations of metal oxides, melting temperatures and "cook" times.

Most colored glass used in the art market is manufactured in volume by

vendors who serve this market, although there are some glassmakers with

the ability to make their own color from raw materials.

History of silicate glass

Wine goblet, mid-19th century. Qajar dynasty. Brooklyn Museum.

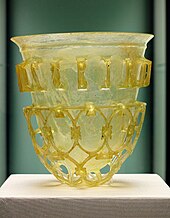

Roman cage cup from the 4th century CE

Studio glass.

Multiple colors within a single object increase the difficulty of

production, as glasses of different colors have different chemical and

physical properties when molten.

Naturally occurring glass, especially the volcanic glass obsidian, was used by many Stone Age

societies across the globe for the production of sharp cutting tools

and, due to its limited source areas, was extensively traded. But in

general, archaeological evidence suggests that the first true glass was

made in coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt.

The earliest known glass objects, of the mid third millennium BCE, were

beads, perhaps initially created as accidental by-products of metal-working (slags) or during the production of faience, a pre-glass vitreous material made by a process similar to glazing.

Glass remained a luxury material, and the disasters

that overtook Late Bronze Age civilizations seem to have brought

glass-making to a halt. Indigenous development of glass technology in South Asia may have begun in 1730 BCE. In ancient China, though, glassmaking seems to have a late start, compared to ceramics and metal work. The term glass developed in the late Roman Empire. It was in the Roman glassmaking center at Trier, now in modern Germany, that the late-Latin term glesum originated, probably from a Germanic word for a transparent, lustrous substance. Glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire in domestic, funerary, and industrial contexts. Examples of Roman glass have been found outside of the former Roman Empire in China, the Baltics, the Middle East and India.

Glass was used extensively during the Middle Ages. Anglo-Saxon glass has been found across England during archaeological excavations of both settlement and cemetery sites. Glass in the Anglo-Saxon period was used in the manufacture of a range of objects including vessels, windows, beads, and was also used in jewelry. From the 10th-century onward, glass was employed in stained glass windows of churches and cathedrals, with famous examples at Chartres Cathedral and the Basilica of Saint Denis. By the 14th-century, architects were designing buildings with walls of stained glass such as Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, (1203–1248) and the East end of Gloucester Cathedral. Stained glass had a major revival with Gothic Revival architecture in the 19th century. With the Renaissance, and a change in architectural style, the use of large stained glass windows became less prevalent. The use of domestic stained glass increased

until most substantial houses had glass windows. These were initially

small panes leaded together, but with the changes in technology, glass

could be manufactured relatively cheaply in increasingly larger sheets.

This led to larger window panes, and, in the 20th-century, to much

larger windows in ordinary domestic and commercial buildings.

In the 20th century, new types of glass such as laminated glass, reinforced glass and glass bricks increased the use of glass as a building material and resulted in new applications of glass. Multi-story buildings are frequently constructed with curtain walls made almost entirely of glass. Similarly, laminated glass has been widely applied to vehicles for windscreens. Optical glass for spectacles has been used since the Middle Ages. The production of lenses has become increasingly proficient, aiding astronomers as well as having other application in medicine and science. Glass is also employed as the aperture cover in many solar energy collectors.

From the 19th century, there was a revival in many ancient glass-making techniques including cameo glass, achieved for the first time since the Roman Empire and initially mostly used for pieces in a neo-classical style. The Art Nouveau movement made great use of glass, with René Lalique, Émile Gallé, and Daum of Nancy producing colored vases and similar pieces, often in cameo glass, and also using luster techniques. Louis Comfort Tiffany

in America specialized in stained glass, both secular and religious,

and his famous lamps. The early 20th-century saw the large-scale factory

production of glass art by firms such as Waterford and Lalique.

From about 1960 onward, there have been an increasing number of small

studios hand-producing glass artworks, and glass artists began to class

themselves as in effect sculptors working in glass, and their works as

part fine arts.

In the 21st century, scientists observe the properties of ancient stained glass windows, in which suspended nanoparticles

prevent UV light from causing chemical reactions that change image

colors, are developing photographic techniques that use similar stained

glass to capture true color images of Mars for the 2019 ESA Mars Rover mission.

Chronology of advances in architectural glass

- 1226: "Broad Sheet" first produced in Sussex.

- 1330: "Crown glass" for art work and vessels first produced in Rouen, France. "Broad Sheet" also produced. Both were also supplied for export.

- 1500s: A method of making mirrors out of plate glass was developed by Venetian glassmakers on the island of Murano, who covered the back of the glass with a mercury-tin amalgam, obtaining near-perfect and undistorted reflection.

- 1620s: "Blown plate" first produced in London. Used for mirrors and coach plates.

- 1678: "Crown glass" first produced in London. This process dominated until the 19th century.

- 1843: An early form of "float glass" invented by Henry Bessemer, pouring glass onto liquid tin. Expensive and not a commercial success.

- 1874: Tempered glass is developed by Francois Barthelemy Alfred Royer de la Bastie (1830–1901) of Paris, France by quenching almost molten glass in a heated bath of oil or grease.

- 1888: Machine-rolled glass introduced, allowing patterns.

- 1898: Wired-cast glass first commercially produced by Pilkington for use where safety or security was an issue.

- 1959: Float glass launched in UK. Invented by Sir Alastair Pilkington.

- Mouth-blown window-glass in Sweden Kosta Glasbruk, (1742) with a pontil mark from the glassblower's pipe

- A building in Canterbury, England, which displays its long history in different building styles and glazing of every century from the 16th to the 20th included.

- Windows in the choir of the Basilica of Saint Denis, one of the earliest uses of extensive areas of glass. (early 13th-century architecture with restored glass of the 19th century)

- "Hardwick Hall, more glass than wall". (late 16th century)

Other types

New chemical glass compositions or new treatment techniques can be

initially investigated in small-scale laboratory experiments. The raw

materials for laboratory-scale glass melts are often different from

those used in mass production because the cost factor has a low

priority. In the laboratory mostly pure chemicals

are used. Care must be taken that the raw materials have not reacted

with moisture or other chemicals in the environment (such as alkali or alkaline earth metal oxides and hydroxides, or boron oxide), or that the impurities are quantified (loss on ignition). Evaporation losses during glass melting should be considered during the selection of the raw materials, e.g., sodium selenite may be preferred over easily evaporating SeO2. Also, more readily reacting raw materials may be preferred over relatively inert ones, such as Al(OH)3 over Al2O3. Usually, the melts are carried out in platinum crucibles to reduce contamination from the crucible material. Glass homogeneity is achieved by homogenizing the raw materials mixture (glass batch), by stirring the melt, and by crushing and re-melting the first melt. The obtained glass is usually annealed to prevent breakage during processing.

To make glass from materials with poor glass forming tendencies, novel

techniques are used to increase cooling rate, or reduce crystal

nucleation triggers. Examples of these techniques include aerodynamic levitation (cooling the melt whilst it floats on a gas stream), splat quenching (pressing the melt between two metal anvils) and roller quenching (pouring the melt through rollers).

Some glass fibers

Fiberglass

Fiberglass (also called glass-reinforced-plastic) is a composite material made up of glass fibers (also called fiberglass or glass friller) embedded in a plastic resin.

It is made by melting glass and stretching the glass into fibers. These

fibers are woven together into a cloth and left to set in a plastic

resin.

Fiberglass filaments are made through a pultrusion process in which the raw materials (sand, limestone, kaolin clay, fluorspar, colemanite, dolomite and other minerals) are melted in a large furnace into a liquid which is extruded through very small orifices (5–25 micrometers in diameter if the glass is E-glass and 9 micrometers if the glass is S-glass).

Fiberglass has the properties of being lightweight and corrosion resistant. Fiberglass is also a good insulator, allowing it to be used to insulate buildings. Most fiberglass is not alkali resistant. Fiberglass also has the property of becoming stronger as the glass ages.

Network glasses

A CD-RW (CD). Chalcogenide glass form the basis of rewritable CD and DVD solid-state memory technology.

Some types of glass that do not include silica as a major constituent

may have physico-chemical properties useful for their application in fiber optics and other specialized technical applications. These include fluoride glass, aluminate and aluminosilicate glass, phosphate glass, borate glass, and chalcogenide glass.

There are three classes of components for oxide glass: network formers, intermediates, and modifiers.

The network formers (silicon, boron, germanium) form a highly

cross-linked network of chemical bonds. The intermediates (titanium,

aluminum, zirconium, beryllium, magnesium, zinc) can act as both

network formers and modifiers, according to the glass composition.

The modifiers (calcium, lead, lithium, sodium, potassium) alter the

network structure; they are usually present as ions, compensated by

nearby non-bridging oxygen atoms, bound by one covalent bond to the

glass network and holding one negative charge to compensate for the

positive ion nearby. Some elements can play multiple roles; e.g. lead can act both as a network former (Pb4+ replacing Si4+), or as a modifier.

The presence of non-bridging oxygen lowers the relative number

of strong bonds in the material and disrupts the network, decreasing the

viscosity of the melt and lowering the melting temperature.

The alkali metal ions are small and mobile; their presence in glass allows a degree of electrical conductivity,

especially in molten state or at high temperature. Their mobility

decreases the chemical resistance of the glass, allowing leaching by

water and facilitating corrosion. Alkaline earth ions, with their two

positive charges and requirement for two non-bridging oxygen ions to

compensate for their charge, are much less mobile themselves and also

hinder diffusion of other ions, especially the alkalis. The most common

commercial glass types contain both alkali and alkaline earth ions

(usually sodium and calcium), for easier processing and satisfying

corrosion resistance. Corrosion resistance of glass can be increased by dealkalization, removal of the alkali ions from the glass surface by reaction with sulfur or fluorine compounds. Presence of alkaline metal ions has also detrimental effect to the loss tangent of the glass, and to its electrical resistance; glass manufactured for electronics (sealing, vacuum tubes, lamps ...) have to take this in account.

Addition of lead(II) oxide lowers melting point, lowers viscosity of the melt, and increases refractive index.

Lead oxide also facilitates solubility of other metal oxides and is

used in colored glass. The viscosity decrease of lead glass melt is very

significant (roughly 100 times in comparison with soda glass); this

allows easier removal of bubbles and working at lower temperatures,

hence its frequent use as an additive in vitreous enamels and glass solders. The high ionic radius of the Pb2+

ion renders it highly immobile in the matrix and hinders the movement

of other ions; lead glasses therefore have high electrical resistance,

about two orders of magnitude higher than soda-lime glass (108.5 vs 106.5 Ω⋅cm, DC at 250 °C). For more details, see lead glass.

Addition of fluorine lowers the dielectric constant of glass. Fluorine is highly electronegative

and attracts the electrons in the lattice, lowering the polarizability

of the material. Such silicon dioxide-fluoride is used in manufacture of

integrated circuits as an insulator. High levels of fluorine doping lead to formation of volatile SiF2O and such glass is then thermally unstable. Stable layers were achieved with dielectric constant down to about 3.5–3.7.

Amorphous metals

Samples of amorphous metal, with millimeter scale

In the past, small batches of amorphous metals

with high surface area configurations (ribbons, wires, films, etc.)

have been produced through the implementation of extremely rapid rates

of cooling. This was initially termed "splat cooling" by doctoral

student W. Klement at Caltech, who showed that cooling rates on the

order of millions of degrees per second is sufficient to impede the

formation of crystals, and the metallic atoms become "locked into" a

glassy state. Amorphous metal wires have been produced by sputtering

molten metal onto a spinning metal disk. More recently a number of

alloys have been produced in layers with thickness exceeding 1

millimeter. These are known as bulk metallic glasses (BMG). Liquidmetal Technologies

sell a number of zirconium-based BMGs. Batches of amorphous steel have

also been produced that demonstrate mechanical properties far exceeding

those found in conventional steel alloys.

In 2004, NIST researchers presented evidence that an isotropic

non-crystalline metallic phase (dubbed "q-glass") could be grown from

the melt. This phase is the first phase, or "primary phase", to form in

the Al-Fe-Si system during rapid cooling. Experimental evidence

indicates that this phase forms by a first-order transition. Transmission electron microscopy

(TEM) images show that the q-glass nucleates from the melt as discrete

particles, which grow spherically with a uniform growth rate in all

directions. The diffraction pattern shows it to be an isotropic glassy phase. Yet there is a nucleation barrier, which implies an interfacial discontinuity (or internal surface) between the glass and the melt.

Electrolytes

Electrolytes or molten salts are mixtures of different ions.

In a mixture of three or more ionic species of dissimilar size and

shape, crystallization can be so difficult that the liquid can easily be

supercooled into a glass.

The best-studied example is Ca0.4K0.6(NO3)1.4.

Glass electrolytes in the form of Ba-doped Li-glass and Ba-doped

Na-glass have been proposed as solutions to problems identified with

organic liquid electrolytes used in modern lithium-ion battery cells.

Aqueous solutions

Some aqueous solutions can be supercooled into a glassy state, for instance LiCl:RH2O (a solution of lithium chloride salt and water molecules) in the composition range 4 less than R less than 8. An aqueous solution containing sugar has a glassy state and can be used as a surfactant.

Molecular liquids

A molecular liquid is composed of molecules that do not form a covalent network but interact only through weak van der Waals forces or through transient hydrogen bonds.

Many molecular liquids can be supercooled into a glass; some are excellent glass formers that normally do not crystallize. An example of this is sugar glass.

Under extremes of pressure and temperature solids may exhibit large structural and physical changes that can lead to polyamorphic phase transitions. In 2006 Italian scientists created an amorphous phase of carbon dioxide using extreme pressure. The substance was named amorphous carbonia (a-CO2) and exhibits an atomic structure resembling that of silica.

Polymers

Important polymer glasses include amorphous and glassy pharmaceutical

compounds. These are useful because the solubility of the compound is

greatly increased when it is amorphous compared to the same crystalline

composition. Many emerging pharmaceuticals are practically insoluble in

their crystalline forms.

Colloidal glasses

Concentrated colloidal suspensions may exhibit a distinct glass transition as function of particle concentration or density.

In cell biology, there is recent evidence suggesting that the cytoplasm behaves like a colloidal glass approaching the liquid-glass transition. During periods of low metabolic activity, as in dormancy, the cytoplasm vitrifies and prohibits the movement to larger cytoplasmic particles while allowing the diffusion of smaller ones throughout the cell.

Glass-ceramics

A high-strength glass-ceramic cooktop with negligible thermal expansion.

Glass-ceramic materials share many properties with both non-crystalline glass and crystalline ceramics.

They are formed as a glass, and then partially crystallized by heat

treatment. For example, the microstructure of whiteware ceramics

frequently contains both amorphous and crystalline phases. Crystalline grains are often embedded within a non-crystalline intergranular phase of grain boundaries. When applied to whiteware ceramics, vitreous means the material has an extremely low permeability to liquids, often but not always water, when determined by a specified test regime.

The term mainly refers to a mix of lithium and aluminosilicates

that yields an array of materials with interesting thermomechanical

properties. The most commercially important of these have the

distinction of being impervious to thermal shock. Thus, glass-ceramics

have become extremely useful for countertop cooking. The negative thermal expansion

coefficient (CTE) of the crystalline ceramic phase can be balanced with

the positive CTE of the glassy phase. At a certain point (~70%

crystalline) the glass-ceramic has a net CTE near zero. This type of glass-ceramic exhibits excellent mechanical properties and can sustain repeated and quick temperature changes up to 1000 °C.

Structure

As in other amorphous solids, the atomic structure of a glass lacks the long-range periodicity observed in crystalline solids. Due to chemical bonding characteristics, glasses do possess a high degree of short-range order with respect to local atomic polyhedra.

The amorphous structure of glassy silica (SiO2) in two dimensions. No long-range order is present, although there is local ordering with respect to the tetrahedral arrangement of oxygen (O) atoms around the silicon (Si) atoms.

Formation from a supercooled liquid

In physics, the standard definition of a glass (or vitreous solid) is a solid formed by rapid melt quenching, although the term glass is often used to describe any amorphous solid that exhibits a glass transition temperature Tg. For melt quenching, if the cooling is sufficiently rapid (relative to the characteristic crystallization time) then crystallization is prevented and instead the disordered atomic configuration of the supercooled liquid is frozen into the solid state at Tg.

The tendency for a material to form a glass while quenched is called

glass-forming ability. This ability can be predicted by the rigidity theory. Generally, a glass exists in a structurally metastable state with respect to its crystalline form, although in certain circumstances, for example in atactic polymers, there is no crystalline analogue of the amorphous phase.

Glass is sometimes considered to be a liquid due to its lack of a first-order phase transition

where certain thermodynamic variables such as volume, entropy and enthalpy are discontinuous through the glass transition range. The glass transition may be described as analogous to a second-order phase transition where the intensive thermodynamic variables such as the thermal expansivity and heat capacity are discontinuous.

Nonetheless, the equilibrium theory of phase transformations does not

entirely hold for glass, and hence the glass transition cannot be

classed as one of the classical equilibrium phase transformations in

solids.

Glass is an amorphous solid. It exhibits an atomic structure

close to that observed in the supercooled liquid phase but displays all

the mechanical properties of a solid.

The notion that glass flows to an appreciable extent over extended

periods of time is not supported by empirical research or theoretical

analysis.

Laboratory measurements of room temperature glass flow do show a motion

consistent with a material viscosity on the order of 1017–1018 Pa s.

Although the atomic structure of glass shares characteristics of the structure in a supercooled liquid, glass tends to behave as a solid below its glass transition temperature. A supercooled liquid behaves as a liquid, but it is below the freezing point

of the material, and in some cases will crystallize almost instantly if

a crystal is added as a core. The change in heat capacity at a glass

transition and a melting transition of comparable materials are typically of the same order of magnitude, indicating that the change in active degrees of freedom is comparable as well. Both in a glass and in a crystal it is mostly only the vibrational degrees of freedom that remain active, whereas rotational and translational

motion is arrested. This helps to explain why both crystalline and

non-crystalline solids exhibit rigidity on most experimental time

scales.

Behavior of antique glass

The observation that old windows are sometimes found to be thicker at

the bottom than at the top is often offered as supporting evidence for

the view that glass flows over a timescale of centuries, the assumption

being that the glass has exhibited the liquid property of flowing from

one shape to another.

This assumption is incorrect, as once solidified, glass stops flowing.

The reason for the observation is that in the past, when panes of glass

were commonly made by glassblowers, the technique used was to spin molten glass so as to create a round, mostly flat and even plate (the crown glass

process, described above). This plate was then cut to fit a window. The

pieces were not absolutely flat; the edges of the disk became a

different thickness as the glass spun. When installed in a window frame,

the glass would be placed with the thicker side down both for the sake

of stability and to prevent water accumulating in the lead cames at the bottom of the window. Occasionally, such glass has been found installed with the thicker side at the top, left or right.

Mass production of glass window panes in the early twentieth

century caused a similar effect. In glass factories, molten glass was

poured onto a large cooling table and allowed to spread. The resulting

glass is thicker at the location of the pour, located at the center of

the large sheet. These sheets were cut into smaller window panes with

nonuniform thickness, typically with the location of the pour centered

in one of the panes (known as "bull's-eyes") for decorative effect.

Modern glass intended for windows is produced as float glass and is very uniform in thickness.

Several other points can be considered that contradict the "cathedral glass flow" theory:

- Writing in the American Journal of Physics, the materials engineer Edgar D. Zanotto states "... the predicted relaxation time for GeO2 at room temperature is 1032 years. Hence, the relaxation period (characteristic flow time) of cathedral glasses would be even longer." (1032 years is many times longer than the estimated age of the universe.)

- If medieval glass has flowed perceptibly, then ancient Roman and Egyptian objects should have flowed proportionately more—but this is not observed. Similarly, prehistoric obsidian blades should have lost their edge; this is not observed either (although obsidian may have a different viscosity from window glass).

- If glass flows at a rate that allows changes to be seen with the naked eye after centuries, then the effect should be noticeable in antique telescopes. Any slight deformation in the antique telescopic lenses would lead to a dramatic decrease in optical performance, a phenomenon that is not observed. However, the glass used in telescopic lenses is generally different from what is used in windowpanes.