Repressed memories are memories that have been unconsciously blocked due to the memory being associated with a high level of stress or trauma. The theory postulates that even though the individual cannot recall the memory, it may still be affecting them subconsciously,

and that these memories can emerge later into the consciousness. Ideas

on repressed memory hiding trauma from awareness were an important part

of Sigmund Freud's early work on psychoanalysis. He later took a different view.

The existence of repressed memories is an extremely controversial

topic in psychology; although some studies have concluded that it can

occur in a varying but generally small percentage of victims of trauma,

many other studies dispute its existence entirely.

Some psychologists support the theory of repressed memories and claim

that repressed memories can be recovered through therapy, but most

psychologists argue that this is in fact rather a process through which

false memories are created by blending actual memories and outside

influences.

One study concluded that repressed memories were a cultural symptom for

want of written proof of their existence before the nineteenth century,

but its results were disputed by some psychologists, and a work

discussing a repressed memory from 1786 was eventually acknowledged,

though the others stand by their hypothesis.

According to the American Psychological Association, it is not possible to distinguish repressed memories from false ones without corroborating evidence. The term repressed memory is sometimes compared to the term dissociative amnesia, which is defined in the DSM-V

as an "inability to recall autobiographical information. This amnesia

may be localized (i.e., an event or period of time), selective (i.e., a

specific aspect of an event), or generalized (i.e., identity and life

history)."

According to the Mayo Clinic, amnesia

refers to any instance in which memories stored in the long-term memory

are completely or partially forgotten, usually due to brain injury.

According to proponents of the existence of repressed memories, such

memories can be recovered years or decades after the event, most often

spontaneously, triggered by a particular smell, taste, or other

identifier related to the lost memory, or via suggestion during psychotherapy.

History

It was initially claimed that there was no documented writing about repressed memories or dissociative amnesia (as it is sometimes referred to), before the 1800s.

This finding, by Harrison G. Pope, was based on a competition in which

entrants could win $1000 if they could identify "a pre-1800 literary

example of traumatic memory that has been repressed by an otherwise

healthy individual, and then recovered." Pope claimed that no entrant

had satisfied the criteria. Ross Cheit, a political scientist at Brown

University, cited Nina, a 1786 opera by the French composer Nicolas Dalayrac.

The concept of repressed memory originated with Sigmund Freud in his 1896 essay Zur Ätiologie der Hysterie ("On the etiology of hysteria").

One of the studies published in his essay involved a young woman by the name of Anna O.

Among her many ailments, she suffered from stiff paralysis on the right

side of her body. Freud stated her symptoms to be attached to

psychological traumas. The painful memories had separated from her

consciousness and brought harm to her body. Freud used hypnosis to treat

Anna O. She is reported to have gained slight mobility on her right

side. Freud's repressed memory theory joined his philosophy of psychoanalysis. Repressed memory has remained a heavily debated topic inside of Freud's psychoanalysis philosophy.

Research

Some research indicates that memories of child sexual abuse and other traumatic incidents may be forgotten. Evidence of the spontaneous recovery of traumatic memories has been shown, and recovered memories of traumatic childhood abuse have been corroborated.

Forgetting trauma, however, does not necessarily imply that the trauma

was repressed. It is also possible that trauma may be forgotten through

normal cognitive processes. This theory is supported by evidence that

forgetting trauma most often occurs when the trauma did not cause a

strong emotional reaction in the moment it was experienced.

Van der Kolk and Fisler's research shows that traumatic memories

are retrieved, at least at first, in the form of mental imprints that

are dissociated. These imprints are of the affective and sensory

elements of the traumatic experience. Clients have reported the slow

emergence of a personal narrative that can be considered explicit

(conscious) memory. The level of emotional significance of a memory

correlates directly with the memory's veracity. Studies of subjective

reports of memory show that memories of highly significant events are

unusually accurate and stable over time.

The imprints of traumatic experiences appear to be qualitatively

different from those of nontraumatic events. Traumatic memories may be

coded differently from ordinary event memories, possibly because of

alterations in attentional focusing or the fact that extreme emotional

arousal interferes with the memory functions of the hippocampus.

Another possibility is that traumatic events are pushed out of

consciousness until a later events elicits or triggers a psychological

response. A high percentage of female psychiatric in-patients, and outpatients have reported experiencing histories of childhood sexual abuse. Other

clinical studies have concluded that patients who experienced incestuous

abuse reported higher suicide attempts and negative identity formation as well as more disturbances in interpersonal relationships.

There has also been significant questioning of the reality of

repressed memories. There is considerable evidence that rather than

being pushed out of consciousness, the difficulty with traumatic

memories for most people are their intrusiveness and inability to

forget. One case that is held up as definitive proof of the reality of repressed memories, recorded by David Corwin has been criticized by Elizabeth Loftus

and Melvin Guyer for ignoring the context of the original complaint and

falsely presenting the sexual abuse as unequivocal and true when in

reality there was no definitive proof.

Retrospective studies (studying the extent to which participants

can recall past events) depend critically on the ability of informants

to recall accurate memories.

The issue of reliability in participants’ introspective abilities has

been questioned by modern psychologists. In other words, a participant

accurately recalling and remembering their own past memories is highly

criticized, because memories are undoubtedly influenced by external,

environmental factors.

Psychologists Elizabeth Loftus and Katherine Ketcham are authors of the seminal work on the fallacy of repressed memory, The Myth of Repressed Memory (St. Martin's Press, 1994).

Cause

It is hypothesised that repression

may be one method used by individuals to cope with traumatic memories,

by pushing them out of awareness (perhaps as an adaptation via psychogenic amnesia) to allow a child to maintain attachment to a person on whom they are dependent for survival. Researchers have proposed that repression can operate on a social level as well.

Other theoretical causes of forgotten memories have stemmed from the idea of Retrieval-Influenced Forgetting,

which states that “false” memories will be more accurately recalled

when rehearsed more, than when actual memories get rehearsed. In this

scenario, the action of rehearsing a falsified memory can actually take

precedence over the actual memory that a person experiences. Anderson et

al.

discovered that rehearsal of novel information exhibits inhibitive

processes on one’s ability to remember or recall the prior (real)

memory. This conclusion indicates that past memories can be easily

forgotten, simply by attending to “real”, novel memories that are

brought into awareness.

Authenticity

Memories can be accurate, but they are not always accurate. For example, eyewitness testimony even of relatively recent dramatic events is notoriously unreliable.

Memories of events are a mix of fact overlaid with emotions, mingled

with interpretation and "filled in" with imaginings. Skepticism

regarding the validity of a memory as factual detail is warranted.

For example, one study where victims of documented child abuse were

reinterviewed many years later as adults, 38% of the women denied any

memory of the abuse.

Arguments against the existence of "traumatic amnesia" note that

various manipulations can be used to implant false memories (sometimes

called "pseudomemories"). These can be quite compelling for those who

develop them, and can include details that make them seem credible to

others. A classic experiment in memory research, conducted by Elizabeth Loftus,

became widely known as "Lost in the Mall"; in this, subjects were given

a booklet containing three accounts of real childhood events written by

family members and a fourth account of a wholly fictitious event of

being lost in a shopping mall. A quarter of the subjects reported

remembering the fictitious event, and elaborated on it with extensive

circumstantial detail.

This experiment inspired many others, and in one of these, Porter et

al. could convince about half of his subjects that they had survived a

vicious animal attack in childhood.

Such experimental studies have been criticized in particular about whether the findings are really relevant to trauma memories and psychotherapeutic situations. Nevertheless, these studies prompted public and professional concern about recovered memory therapy for past sexual abuse.

When memories are "recovered" after long periods of amnesia,

particularly when extraordinary means were used to secure the recovery

of memory, it is now widely (but not universally) accepted that the

memories are quite likely to be false, i.e. of incidents that had not

occurred.

It is thus recognised by professional organizations that a risk of

implanting false memories is associated with some similar types of

therapy. The American Psychiatric Association advises: "...most

leaders in the field agree that although it is a rare occurrence, a

memory of early childhood abuse that has been forgotten can be

remembered later. However, these leaders also agree that it is possible

to construct convincing pseudomemories for events that never occurred.

Nevertheless, many therapists believe in the authenticity of the

recovered memories that they hear from their clients. In a non-random

study by Loftus and Herzog (1991) with 16 clinicians, 13 (81%) said that

they invariably believed their clients. The most common basis for this

belief was the patient’s symptomology (low self-esteem, sexual

dysfunction, self-destructive behaviour) or body memories (voice frozen

etc.).

The mechanism(s) by which both of these phenomena happen are not

well understood and, at this point it is impossible, without other

corroborative evidence, to distinguish a true memory from a false one."

Sheflin and Brown state that a total of 25 studies on amnesia for child

sexual abuse exist and that they demonstrate amnesia in their study

subpopulations. However, an editorial in the British Medical Journal states on the Sheflin and Brown study that "on critical examination, the scientific evidence for repression crumbles."

Obviously, not all therapists agree that false memories are a

major risk of psychotherapy and they argue that this idea overstates the

data and is untested. Several studies have reported high percentages of the corroboration of recovered memories,

and some authors have claimed that the false memory movement has tended

to conceal or omit evidence of (the) corroboration" of recovered

memories.

Both true and false "memories" can be recovered using memory work

techniques, but there is no evidence that reliable discriminations can

be made between them. Some believe that memories "recovered" under hypnosis are particularly likely to be false.

According to The Council on Scientific Affairs for the American Medical

Association, recollections obtained during hypnosis can involve

confabulations and pseudomemories and appear to be less reliable than

nonhypnotic recall.

Brown et al. estimate that 3 to 5% of laboratory subjects are vulnerable

to post-event misinformation suggestions. They state that 5–8% of the

general population is the range of high-hypnotizability. Twenty-five

percent of those in this range are vulnerable to suggestion of

pseudomemories for peripheral details, which can rise to 80% with a

combination of other social influence factors. They conclude that the

rates of memory errors run 0–5% in adult studies, 3–5% in children's

studies and that the rates of false allegations of child abuse

allegations run 4–8% in the general population.

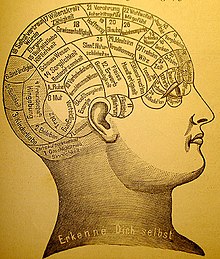

Neurological basis of memory

The neuroscientist Donald Hebb (1904–1985) was the first to distinguish between short-term memory and long-term memory.

According to current theories in neuroscience, things that we "notice"

are stored in short-term memory for up to a few minutes; this memory

depends on "reverberating" electrical activity in neuronal circuits, and

is very easily destroyed by interruption or interference. Memories

stored for longer than this are stored in "long-term memory". Whether

information is stored in long-term memory depends on its "importance";

for any animal, memories of traumatic events are potentially important

for the adaptive value that they have for future avoidance behavior, and

hormones

that are released during stress have a role in determining what

memories are preserved. In humans, traumatic stress is associated with

acute secretion of epinephrine and norepinephrine (adrenaline and noradrenaline) from the adrenal medulla and cortisol from the adrenal cortex.

Increases in these facilitate memory, but chronic stress associated

with prolonged hypersecretion of cortisol may have the opposite effect.

The limbic system

is involved in memory storage and retrieval as well as giving emotional

significance to sensory inputs. Within the limbic system, the hippocampus is important for explicit memory, and for memory consolidation; it is also sensitive to stress hormones, and has a role in recording the emotions of a stressful event. The amygdala may be particularly important in assigning emotional values to sensory inputs.

Although memory distortion occurs in everyday life, the brain mechanisms involved are not easy to study in the laboratory, but neuroimaging

techniques have recently been applied to this subject. In particular,

there have recently been studies of false recognition, where individuals

incorrectly claim to have encountered a novel object or event, and the

results suggest that the hippocampus and several cortical regions may

contribute to such false recognition, while the prefrontal cortex may be

involved in retrieval monitoring that can limit the rate of false

recognition.

Amnesia

Amnesia

is partial or complete loss of memory that goes beyond mere forgetting.

Often it is temporary and involves only part of a person's experience.

Amnesia is often caused by an injury to the brain, for instance after a

blow to the head, and sometimes by psychological trauma. Anterograde amnesia is a failure to remember new experiences that occur after damage to the brain; retrograde amnesia

is the loss of memories of events that occurred before a trauma or

injury. For a memory to become permanent (consolidated), there must be a

persistent change in the strength of connections between particular

neurons in the brain. Anterograde amnesia can occur because this

consolidation process is disrupted; retrograde amnesia can result either

from damage to the site of memory storage or from a disruption in the

mechanisms by which memories can be retrieved from their stores. Many

specific types of amnesia are recognized, including:

- Childhood amnesia is the normal inability to recall memories from the first three years of life. Sigmund Freud observed that not only do humans not remember anything from birth to three years, but they also have “spotty” recollection of anything occurring from three to seven years of age. There are various theories as to why this occurs: some believe that language development is important for efficient storage of long-term memories; others believe that early memories do not persist because the brain is still developing.

- A fugue state, formally dissociative fugue, is a rare condition precipitated by a stressful episode. It is characterized by episode(s) of traveling away from home and creating a new identity.

The form of amnesia that is linked with recovered memories is

dissociative amnesia (formerly known as psychogenic amnesia). This

results from a psychological cause, not by direct damage to the brain,

and is a loss of memory of significant personal information, usually

about traumatic or extremely stressful events. Usually this is seen as a

gap or gaps in recall for aspects of someone's life history, but with

severe acute trauma, such as during wartime, there can be a sudden acute

onset of symptoms.

Effects of trauma on memory

"Betrayal

Trauma Theory" proposes that in cases of childhood abuse, dissociative

amnesia is an adaptive response, and that “victims may need to remain

unaware of the trauma not to reduce suffering but rather to promote

survival.”

When stress interferes with memory,

it is possible that some of the memory is kept by a system that records

emotional experience, but there is no symbolic placement of it in time

or space.

Traumatic memories are retrieved, at least at first, in the form of

dissociated mental imprints of the affective and sensory elements of the

traumatic experience. Clients have reported the slow emergence of a

personal narrative that can be considered explicit (conscious) memory.

Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk divided the effects of traumas on memory functions into four sets:

- Traumatic amnesia; this involves the loss of memories of traumatic experiences. The younger the subject and the longer the traumatic event is, the greater the chance of significant amnesia. He stated that subsequent retrieval of memories after traumatic amnesia is well documented in the literature, with documented examples following natural disasters and accidents, in combat soldiers, in victims of kidnapping, torture and concentration camp experiences, in victims of physical and sexual abuse, and in people who have committed murder.

- Global memory impairment; this makes it difficult for subjects to construct an accurate account of their present and past history. "The combination of lack of autobiographical memory, continued dissociation and of meaning schemes that include victimization, helplessness and betrayal, is likely to make these individuals vulnerable to suggestion and to the construction of explanations for their trauma-related affects that may bear little relationship to the actual realities of their lives"

- Dissociative processes; this refers to memories being stored as fragments and not as unitary wholes.

- Traumatic memories’ sensorimotor organization. Not being able to integrate traumatic memories seems to be linked to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

According to van der Kolk, memories of highly significant events are

usually accurate and stable over time; aspects of traumatic experiences

appear to get stuck in the mind, unaltered by time passing or

experiences that may follow. The imprints of traumatic experiences

appear to be different from those of nontraumatic events, perhaps

because of alterations in attentional focusing or the fact that extreme

emotional arousal interferes with memory.

van der Kolk and Fisler's hypothesis is that under extreme stress, the

memory categorization system based in the hippocampus fails, with these

memories kept as emotional and sensory states. When these traces are

remembered and put into a personal narrative, they are subject to being

condensed, contaminated and embellished upon.

When there is inadequate recovery time between stressful situations, alterations may occur to the stress response

system, some of which may be irreversible, and cause pathological

responses, which may include memory loss, learning deficits and other

maladaptive symptoms. In animal studies, high levels of cortisol

can cause hippocampal damage, which may cause short-term memory

deficits; in humans, MRI studies have shown reduced hippocampal volumes

in combat veterans with PTSD, adults with posttraumatic symptoms and

survivors of repeated childhood sexual or physical abuse. Trauma may

also interfere with implicit memory, where periods of avoidance may be

interrupted by intrusive emotional occurrences with no story to guide

them. A difficult issue is whether those presumably abused accurately

recall their experiences.

Criticism

The existence of repressed memory recovery has not been accepted by mainstream psychology,

nor unequivocally proven to exist, and some experts in the field of

human memory feel that no credible scientific support exists for the

notions of repressed/recovered memories.

A survey revealed that whilst memory and cognition experts tend to be

skeptical of repressed memory, clinicians are much more apt to believe

that traumatic memory is often repressed.

One research report states that a distinction should be made between

spontaneously recovered memories and memories recovered during

suggestions in therapy.

A criticism from Loftus is that recovered memories can be tainted by

the process of recovery, the suggestions used in that process, or even

cultural and environmental influences.

The Working Group on Investigation of Memories of Child Abuse of

the American Psychological Association presented findings mirroring

those of the other professional organizations. The Working Group made

five key conclusions:

- Controversies regarding adult recollections should not be allowed to obscure the fact that child sexual abuse is a complex and pervasive problem in America that has historically gone unacknowledged;

- Most people who were sexually abused as children remember all or part of what happened to them;

- It is possible for memories of abuse that have been forgotten for a long time to be remembered;

- It is also possible to construct convincing pseudo-memories for events that never occurred; and

- There are gaps in our knowledge about the processes that lead to accurate and inaccurate recollections of childhood abuse.

Many critics believe that memories may be distorted and false. Psychologist Elizabeth Loftus

questions the concept of repressed memories and the possibility of them

being accurate. Loftus focuses on techniques that therapists use in

order to help the patients recover their memory. Such techniques include

age regression, guided visualization, trance writing, dream work, body

work, and hypnosis.

Loftus' research indicates that repressed memory faces problems, such as

memory alteration. In one case a teenage boy was able to “conjure a

memory of an event that never occurred.” According to Loftus, if a

stable person could be influenced to remember an event that never

occurred, an emotionally stressed person would be even more susceptible.

Writer Mark Pendergrast has denounced the theory of repressed memories and its applications in sex abuse cases, including in particular the Jerry Sandusky case.

Medico-legal issues

Serious

issues arise when recovered but false memories result in public

allegations; false complaints carry serious consequences for the

accused. Many of those who make false claims sincerely believe the truth

of what they report. A special type of false allegation, the false memory syndrome,

arises typically within therapy, when people report the "recovery" of

childhood memories of previously unknown abuse. The influence of

practitioners' beliefs and practices in the eliciting of false

"memories" and of false complaints has come under particular criticism.

It is generally accepted that people sometimes are unable to recall traumatic experiences. An old version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), published by the American Psychiatric Association,

states that "Dissociative amnesia is characterized by an inability to

recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or

stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by ordinary

forgetfulness."

The term "recovered memory", however, is not listed in DSM-IV or used by any mainstream formal psychotherapy modality.

Legal state

Some

criminal cases have been based on a witness's testimony of recovered

repressed memories, often of alleged childhood sexual abuse. In some

jurisdictions, the statute of limitations

for child abuse cases has been extended to accommodate the phenomena of

repressed memories as well as other factors. The repressed memory

concept came into wider public awareness in the 1980s and 1990s followed

by a reduction of public attention after a series of scandals,

lawsuits, and license revocations.

A U.S. District Court accepted repressed memories as admissible evidence in a specific case. Dalenberg argues that the evidence shows that recovered memory cases should be allowed to be prosecuted in court.

The apparent willingness of courts to credit the recovered

memories of complainants but not the absence of memories by defendants

has been commented on: "It seems apparent that the courts need better

guidelines around the issue of dissociative amnesia in both

populations."

In 1995, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled, in Franklin v. Duncan and Franklin v. Fox, Murray et al. (312 F3d. 423, see also 884 FSupp 1435, N.D. Calif.),

that repressed memory is not admissible as evidence in a legal action

because of its unreliability, inconsistency, unscientific nature,

tendency to be therapeutically induced evidence, and subject to

influence by hearsay and suggestibility. The court overturned the

conviction of a man accused of murdering a nine-year-old girl purely

based upon the evidence of a 21-year-old repressed memory by a lone

witness, who also held a complex personal grudge against the defendant.

In a 1996 ruling, a U.S. District Court allowed repressed memories entered into evidence in court cases.

Jennifer Freyd writes that Ross Cheit's case of suddenly remembered

sexual abuse is one of the most well-documented cases available for the

public to see. Cheit prevailed in two lawsuits, located five additional

victims and tape-recorded a confession.

On December 16, 2005, the Irish Court of Criminal Appeal issued a

certificate confirming a Miscarriage of Justice to a former nun, Nora Wall whose 1999 conviction for child rape was partly based on repressed-memory evidence. The judgement stated that:

There was no scientific evidence of any sort adduced to explain the phenomenon of "flashbacks" and/or "retrieved memory", nor was the applicant in any position to meet such a case in the absence of prior notification thereof.

On August 16, 2010 the United States Second Circuit Court of Appeals

in a case reversed the conviction that relied on claimed victim memories

of childhood abuse stating that "The record here suggests a "reasonable

likelihood" that Jesse Friedman was wrongfully convicted. The "new and

material evidence” in this case is the post-conviction consensus within

the social science community that suggestive memory recovery tactics

can create false memories" (pg 27 FRIEDMAN v. REHAL Docket No. 08-0297).

The ruling goes on to order all previous convictions and plea bargains

relying in repressed memories using common memory recovered techniques

be reviewed.

Clinical relevance

Recovered memory therapy

Recovered memory therapy is a range of psychotherapy methods based on recalling memories of abuse that had previously been forgotten by the patient. The term "recovered memory therapy" is not listed in DSM-IV or used by mainstream formal psychotherapy modality. Opponents of the therapy advance the explanation that therapy can create false memories through suggestion techniques; this has not been corroborated, though some research has shown supportive evidence. Nevertheless, the evidence is questioned by some researchers. It is possible for patients who retract their claims—after deciding their recovered memories are false—to suffer post-traumatic stress disorder due to the trauma of illusory memories.