| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Gallium nitride

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.042.830 |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| GaN | |

| Molar mass | 83.730 g/mol |

| Appearance | yellow powder |

| Density | 6.1 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | >1600 °C |

| Insoluble | |

| Band gap | 3.4 eV (300 K, direct) |

| Electron mobility | 1500 cm2/(V·s) (300 K) |

| Thermal conductivity | 1.3 W/(cm·K) (300 K) |

Refractive index (nD)

|

2.429 |

| Structure | |

| Wurtzite | |

| C6v4-P63mc | |

a = 3.186 Å, c = 5.186 Å

| |

| Tetrahedral | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−110.2 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Gallium phosphide Gallium arsenide Gallium antimonide |

Other cations

|

Boron nitride Aluminium nitride Indium nitride |

Related compounds

|

Aluminium gallium arsenide Indium gallium arsenide Gallium arsenide phosphide Aluminium gallium nitride Indium gallium nitride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Infobox references | |

Gallium nitride (GaN) is a binary III/V direct bandgap semiconductor commonly used in light-emitting diodes since the 1990s. The compound is a very hard material that has a Wurtzite crystal structure. Its wide band gap of 3.4 eV affords it special properties for applications in optoelectronic, high-power and high-frequency devices. For example, GaN is the substrate which makes violet (405 nm) laser diodes possible, without use of nonlinear optical frequency-doubling.

Its sensitivity to ionizing radiation is low (like other group III nitrides), making it a suitable material for solar cell arrays for satellites. Military and space applications could also benefit as devices have shown stability in radiation environments.

Because GaN transistors can operate at much higher temperatures and work at much higher voltages than gallium arsenide (GaAs) transistors, they make ideal power amplifiers at microwave frequencies. In addition, GaN offers promising characteristics for THz devices.

Physical properties

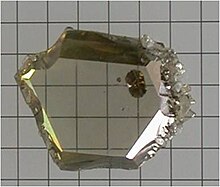

GaN crystal

GaN is a very hard (12±2 GPa), mechanically stable wide bandgap semiconductor material with high heat capacity and thermal conductivity. In its pure form it resists cracking and can be deposited in thin film on sapphire or silicon carbide, despite the mismatch in their lattice constants. GaN can be doped with silicon (Si) or with oxygen to n-type and with magnesium (Mg) to p-type. However, the Si and Mg atoms change the way the GaN crystals grow, introducing tensile stresses and making them brittle. Gallium nitride compounds also tend to have a high dislocation density, on the order of 108 to 1010 defects per square centimeter.

The wide band-gap behavior of GaN is connected to specific changes in

the electronic band structure, charge occupation and chemical bond

regions.

The U.S. Army Research Laboratory (ARL) provided the first measurement of the high field electron velocity in GaN in 1999. Scientists at ARL experimentally obtained a peak steady-state velocity of 1.9 x 107 cm/s, with a transit time of 2.5 picoseconds, attained at an electric field of 225 kV/cm. With this information, the electron mobility was calculated, thus providing data for the design of GaN devices.

Developments

GaN with a high crystalline quality can be obtained by depositing a buffer layer at low temperatures. Such high-quality GaN led to the discovery of p-type GaN, p-n junction blue/UV-LEDs and room-temperature stimulated emission (essential for laser action).

This has led to the commercialization of high-performance blue LEDs and

long-lifetime violet-laser diodes, and to the development of

nitride-based devices such as UV detectors and high-speed field-effect transistors.

LEDs

High-brightness

GaN light-emitting diodes (LEDs) completed the range of primary colors,

and made applications such as daylight visible full-color LED displays,

white LEDs and blue laser devices possible. The first GaN-based high-brightness LEDs used a thin film of GaN deposited via Metal-Organic Vapour Phase Epitaxy (MOVPE) on sapphire. Other substrates used are zinc oxide, with lattice constant mismatch of only 2% and silicon carbide (SiC).

Group III nitride semiconductors are, in general, recognized as one of

the most promising semiconductor families for fabricating optical

devices in the visible short-wavelength and UV region.

Transistors

The very high breakdown voltages, high electron mobility and saturation velocity

of GaN has also made it an ideal candidate for high-power and

high-temperature microwave applications, as evidenced by its high Johnson's figure of merit. Potential markets for high-power/high-frequency devices based on GaN include microwave radio-frequency

power amplifiers (such as those used in high-speed wireless data

transmission) and high-voltage switching devices for power grids. A

potential mass-market application for GaN-based RF transistors is as the microwave source for microwave ovens, replacing the magnetrons

currently used. The large band gap means that the performance of GaN

transistors is maintained up to higher temperatures (~400 °C) than silicon transistors (~150 °C) because it lessens the effects of thermal generation of charge carriers that are inherent to any semiconductor. The first gallium nitride metal semiconductor field-effect transistors (GaN MESFET) were experimentally demonstrated in 1993 and they are being actively developed.

In 2010 the first enhancement-mode GaN transistors became generally available. Only n-channel transistors were available.

These devices were designed to replace power MOSFETs in applications

where switching speed or power conversion efficiency is critical. These

transistors, also called eGaN FETs, are built by growing a thin layer

of GaN on top of a standard silicon wafer. This allows the eGaN FETs to

maintain costs similar to silicon power MOSFETs but with the superior

electrical performance of GaN.

Applications

LEDs

GaN-based violet laser diodes are used to read Blu-ray Discs. The mixture of GaN with In (InGaN) or Al (AlGaN) with a band gap dependent on ratio of In or Al to GaN allows the manufacture of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with colors that can go from red to ultra-violet.

Transistors

GaN transistors are suitable for high frequency, high voltage, high temperature and high efficiency applications.

GaN HEMTs

have been offered commercially since 2006, and have found immediate use

in various wireless infrastructure applications due to their high

efficiency and high voltage operation. A second generation of devices

with shorter gate lengths will address higher frequency telecom and

aerospace applications.

GaN based MOSFET and MESFET

transistors also offer advantages including lower loss in high power

electronics, especially in automotive and electric car applications. Since 2008 these can be formed on a silicon substrate. High-voltage (800 V) Schottky barrier diodes (SBDs) have also been made.

GaN-based electronics (not pure GaN) has the potential to

drastically cut energy consumption, not only in consumer applications

but even for power transmission utilities.

Unlike silicon transistors which switch off due to power surges, GaN transistors are typically depletion mode

devices (i.e. on / resistive when the gate-source voltage is zero).

Several methods have been proposed to reach normally-off (or E-mode)

operation, which is necessary for use in power electronics:

- the implantation of fluorine ions under the gate (the negative charge of the F-ions favors the depletion of the channel)

- the use of a MIS-type gate stack, with recess of the AlGaN

- the integration of a cascaded pair constituted by a normally-on GaN transistor and a low voltage silicon MOSFET

- the use of a p-type layer on top of the AlGaN/GaN heterojunction

Radars

They are also utilized in military electronics such as active electronically scanned array radars.

The U.S. Army funded Lockheed Martin

to incorporate GaN active-device technology into the AN/TPQ-53 radar

system to replace two medium-range radar systems, the AN/TPQ-36 and the

AN/TPQ-37.

The AN/TPQ-53 radar system was designed to detect, classify, track, and

locate enemy indirect fire systems, as well as unmanned aerial systems.

The AN/TPQ-53 radar system provided enhanced performance, greater

mobility, increased reliability and supportability, lower life-cycle

cost, and reduced crew size compared to the AN/TPQ-36 and the AN/TPQ-37

systems.

Lockheed Martin fielded other tactical operational radars with

GaN technology in 2018, including TPS-77 Multi Role Radar System

deployed to Latvia and Romania. In 2019, Lockheed Martin's partner ELTA Systems Limited, developed a GaN-based ELM-2084

Multi Mission Radar that was able to detect and track air craft and

ballistic targets, while providing fire control guidance for missile

interception or air defense artillery.

Nanoscale

GaN nanotubes and nanowires are proposed for applications in nanoscale electronics, optoelectronics and biochemical-sensing applications.

Spintronics potential

When doped with a suitable transition metal such as manganese, GaN is a promising spintronics material (magnetic semiconductors).

Synthesis

Bulk substrates

GaN crystals can be grown from a molten Na/Ga melt held under 100 atmospheres of pressure of N2 at 750 °C. As Ga will not react with N2 below 1000 °C, the powder must be made from something more reactive, usually in one of the following ways:

- 2 Ga + 2 NH3 → 2 GaN + 3 H2

- Ga2O3 + 2 NH3 → 2 GaN + 3 H2O

Gallium nitride can also be synthesized by injecting ammonia gas into

molten gallium at 900-980 °C at normal atmospheric pressure.

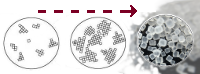

Molecular beam epitaxy

Commercially, GaN crystals can be grown using molecular beam epitaxy or metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy.

This process can be further modified to reduce dislocation densities.

First, an ion beam is applied to the growth surface in order to create

nanoscale roughness. Then, the surface is polished. This process takes

place in a vacuum.

Safety

GaN dust is an irritant to skin, eyes and lungs. The environment, health and safety aspects of gallium nitride sources (such as trimethylgallium and ammonia) and industrial hygiene monitoring studies of MOVPE sources have been reported in a 2004 review.

Bulk GaN is non-toxic and biocompatible. Therefore, it may be used in the electrodes and electronics of implants in living organisms.