Software as a service (SaaS /sæs/) (also known as subscribeware or rentware) is a software licensing and delivery model in which software is licensed on a subscription basis and is centrally hosted. It is sometimes referred to as "on-demand software", and was formerly referred to as "software plus services" by Microsoft.

SaaS applications are also known as Web-based software, on-demand software and hosted software. The term "software as a service" (SaaS) is considered to be part of the nomenclature of cloud computing, along with infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), desktop as a service (DaaS), managed software as a service (MSaaS), mobile backend as a service (MBaaS), datacenter as a service (DCaaS), and information technology management as a service (ITMaaS).

SaaS apps are typically accessed by users using a thin client, e.g. via a web browser. SaaS has become a common delivery model for many business applications, including office software, messaging software, payroll processing software, DBMS software, management software, CAD software, development software, gamification, virtualization, accounting, collaboration, customer relationship management (CRM), management information systems (MIS), enterprise resource planning (ERP), invoicing, human resource management (HRM), talent acquisition, learning management systems, content management (CM), geographic information systems (GIS), and service desk management. SaaS has been incorporated into the strategy of nearly all leading enterprise software companies.

According to a Gartner estimate, SaaS sales in 2018 were expected to grow 23% to $72 billion.

SaaS applications are also known as Web-based software, on-demand software and hosted software. The term "software as a service" (SaaS) is considered to be part of the nomenclature of cloud computing, along with infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), desktop as a service (DaaS), managed software as a service (MSaaS), mobile backend as a service (MBaaS), datacenter as a service (DCaaS), and information technology management as a service (ITMaaS).

SaaS apps are typically accessed by users using a thin client, e.g. via a web browser. SaaS has become a common delivery model for many business applications, including office software, messaging software, payroll processing software, DBMS software, management software, CAD software, development software, gamification, virtualization, accounting, collaboration, customer relationship management (CRM), management information systems (MIS), enterprise resource planning (ERP), invoicing, human resource management (HRM), talent acquisition, learning management systems, content management (CM), geographic information systems (GIS), and service desk management. SaaS has been incorporated into the strategy of nearly all leading enterprise software companies.

According to a Gartner estimate, SaaS sales in 2018 were expected to grow 23% to $72 billion.

History

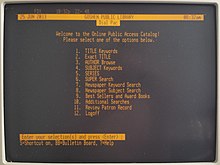

Centralized hosting of business applications dates back to the 1960s. Starting in that decade, IBM and other mainframe providers conducted a service bureau business, often referred to as time-sharing or utility computing. Such services included offering computing power and database storage to banks and other large organizations from their worldwide data centers.

The expansion of the Internet during the 1990s brought about a new class of centralized computing, called application service providers

(ASP). ASPs provided businesses with the service of hosting and

managing specialized business applications, with the goal of reducing

costs through central administration and through the solution provider's

specialization in a particular business application. Two of the world's

pioneers and largest ASPs were USI, which was headquartered in the

Washington, DC area, and Futurelink Corporation, headquartered in Irvine, California.

Software as a Service essentially extends the idea of the ASP model. The term software as a service (SaaS), however, is commonly used in more specific settings:

- While most initial ASP's focused on managing and hosting third-party independent software vendors' software, as of 2012 SaaS vendors typically develop and manage their own software.

- Whereas many initial ASPs offered more traditional client-server applications, which require installation of software on users' personal computers, SaaS solutions of today rely predominantly on the Web and only requires a web browser to use.

- Whereas the software architecture used by most initial ASPs mandated maintaining a separate instance of the application for each business, as of 2012 SaaS solutions normally utilize a multitenant architecture, in which the application serves multiple businesses and users, and partitions its data accordingly.

The acronym first appeared in the goods and services description of a USPTO trademark, filed on September 23, 1985.

DbaaS (database as a service) has emerged as a sub-variety of SaaS, and is a type of cloud database.

Distribution

The

cloud (or SaaS) model has no physical need for indirect distribution

because it is not distributed physically and is deployed almost

instantaneously, thereby negating the need for traditional partners and

middlemen. However, as the market has grown, SaaS and managed service

players have been forced to try to redefine their role.

Pricing

Unlike traditional software, which is conventionally sold as a perpetual license

with an up-front cost (and an optional ongoing support fee), SaaS

providers generally price applications using a subscription fee, most

commonly a monthly fee or an annual fee.

Consequently, the initial setup cost for SaaS is typically lower than

the equivalent enterprise software. SaaS vendors typically price their

applications based on some usage parameters, such as the number of users

using the application. However, because in a SaaS environment

customers' data reside with the SaaS vendor, opportunities also exist to

charge per transaction, event, or other units of value, such as the

number of processors required.

The relatively low cost for user provisioning (i.e., setting up a new customer) in a multitenant environment enables some SaaS vendors to offer applications using the freemium model.

In this model, a free service is made available with limited

functionality or scope, and fees are charged for enhanced functionality

or larger scope.

Some other SaaS applications are completely free to users, with revenue

being derived from alternative sources such as advertising.

A key driver of SaaS growth is SaaS vendors' ability to provide a

price that is competitive with on-premises software. This is consistent

with the traditional rationale for outsourcing IT systems, which

involves applying economies of scale to application operation, i.e., an outside service provider may be able to offer better, cheaper, more reliable applications.

Architecture

The vast majority of SaaS solutions are based on a multitenant architecture. With this model, a single version of the application, with a single configuration (hardware, network, operating system), is used for all customers ("tenants"). To support scalability, the application can be installed on multiple machines (called horizontal scaling).

In some cases, a second version of the application is set up to offer a

select group of customers access to pre-release versions of the

applications (e.g., a beta version) for testing

purposes. This is contrasted with traditional software, where multiple

physical copies of the software — each potentially of a different

version, with a potentially different configuration, and often

customized — are installed across various customer sites. In this traditional model, each version of the application is based on a unique code.

Although an exception rather than the norm, some SaaS solutions do not use multitenancy, or use other mechanisms—such as virtualization—to cost-effectively manage a large number of customers in place of multitenancy. Whether multitenancy is a necessary component for software as a service is a topic of controversy.

There are two main varieties of SaaS:

- Vertical SaaS

- Software which answers the needs of a specific industry (e.g., software for the healthcare, agriculture, real estate, finance industries).

- Horizontal SaaS

- The products which focus on a software category (marketing, sales, developer tools, HR) but are industry neutral.

Characteristics

Although

not all software-as-a-service applications share all traits, the

characteristics below are common among many SaaS applications:

Configuration and customization

SaaS applications similarly support what is traditionally known as application configuration. In other words, like traditional enterprise software, a single customer can alter the set of configuration options (a.k.a. parameters) that affect its functionality and look-and-feel.

Each customer may have its own settings (or: parameter values) for the

configuration options. The application can be customized to the degree

it was designed for based on a set of predefined configuration options.

For example, to support customers' common need to change an

application's look-and-feel so that the application appears to be having

the customer's brand (or—if so desired—co-branded), many SaaS applications let customers provide (through a self-service

interface or by working with application provider staff) a custom logo

and sometimes a set of custom colors. The customer cannot, however,

change the page layout unless such an option was designed for.

Accelerated feature delivery

SaaS applications are often updated more frequently than traditional software, in many cases on a weekly or monthly basis. This is enabled by several factors:

- The application is hosted centrally, so an update is decided and executed by the provider, not by customers.

- The application only has a single configuration, making development testing faster.

- The application vendor does not have to expend resources updating and maintaining backdated versions of the software, because there is only a single version.

- The application vendor has access to all customer data, expediting design and regression testing.

- The solution provider has access to user behavior within the application (usually via web analytics), making it easier to identify areas worthy of improvement.

Accelerated feature delivery is further enabled by agile software development methodologies. Such methodologies, which have evolved in the mid-1990s, provide a set of software development tools and practices to support frequent software releases.

Open integration protocols

Because

SaaS applications cannot access a company's internal systems (databases

or internal services), they predominantly offer integration protocols and application programming interfaces (APIs) that operate over a wide area network. Typically, these are protocols based on HTTP, REST, and SOAP.

The ubiquity of SaaS applications and other Internet services and

the standardization of their API technology has spawned the development

of mashups,

which are lightweight applications that combine data, presentation and

functionality from multiple services, creating a compound service.

Mashups further differentiate SaaS applications from on-premises

software as the latter cannot be easily integrated outside a company's firewall.

Collaborative (and "social") functionality

Inspired by the success of online social networks and other so-called web 2.0 functionality, many SaaS applications offer features that let their users collaborate and share information.

For example, many project management

applications delivered in the SaaS model offer—in addition to

traditional project planning functionality—collaboration features

letting users comment on tasks and plans and share documents within and

outside an organization. Several other SaaS applications let users vote

on and offer new feature ideas.

Although some collaboration-related functionality is also

integrated into on-premises software, (implicit or explicit)

collaboration between users or different customers is only possible with

centrally hosted software.

OpenSaas

OpenSaaS refers to software as a service (SaaS) based on open source

code. Similar to SaaS applications, Open SaaS is a web-based

application that is hosted, supported and maintained by a service

provider. While the roadmap for Open SaaS applications is defined by its

community of users, upgrades and product enhancements are managed by a

central provider. The term was coined in 2011 by Dries Buytaert, creator of the Drupal content management framework.

Andrew Hoppin, a former Chief Information Officer for the New York State Senate, has been a vocal advocate of OpenSaaS for government, calling it "the future of government innovation." He points to WordPress

and Why Unified as a successful example of an OpenSaaS software

delivery model that gives customers "the best of both worlds, and more

options. The fact that it is open source means that they can start

building their websites by self-hosting WordPress and customizing their

website to their heart’s content. Concurrently, the fact that WordPress

is SaaS means that they don’t have to manage the website at all -- they

can simply pay WordPress.com to host it."

Drupal Gardens, a free web hosting platform based on the open source Drupal content management system, offers another example of what Forbes

contributor Dan Woods calls a "new open-source model for SaaS".

According to Woods, "Open source provides the escape hatch. In Drupal

Gardens, users will be able to press a button and get a source code

version of the Drupal code that runs their site along with the data from

the database. Then, you can take that code, put it up at one of the

hosting companies, and you can do anything that you would like to do."

Adoption drivers

Several

important changes to the software market and technology landscape have

facilitated the acceptance and growth of SaaS solutions:

- The growing use of web-based user interfaces by applications, along with the proliferation of associated practices (e.g., web design), continuously decreased the need for traditional client-server applications. Consequently, traditional software vendor's investment in software based on fat clients has become a disadvantage (mandating ongoing support), opening the door for new software vendors offering a user experience perceived as more "modern".

- The standardization of web page technologies (HTML, JavaScript, CSS), the increasing popularity of web development as a practice, and the introduction and ubiquity of web application frameworks like Ruby on Rails or Laravel (PHP) gradually reduced the cost of developing new SaaS solutions, and enabled new solution providers to come up with competitive solutions, challenging traditional vendors.

- The increasing penetration of broadband Internet access enabled remote centrally hosted applications to offer speed comparable to on-premises software.

- The standardization of the HTTPS protocol as part of the web stack provided universally available lightweight security that is sufficient for most everyday applications.

- The introduction and wide acceptance of lightweight integration protocols such as REST and SOAP enabled affordable integration between SaaS applications (residing in the cloud) with internal applications over wide area networks and with other SaaS applications.

- Implementing a Product Led Growth framework (Product Led Growth is a business development strategy that leverages product usage to drive customer acquisitions, conversions, and market expansion.) helps company lower costs, get to market more quickly, and more effectively produce the Saas Product that customers want.

Adoption challenges

Some limitations slow down the acceptance of SaaS and prohibit it from being used in some cases:

- Because data is stored on the vendor's servers, data security becomes an issue.

- SaaS applications are hosted in the cloud, far away from the application users. This introduces latency into the environment; for example, the SaaS model is not suitable for applications that demand response times in the milliseconds (OLTP).

- Multi-tenant architectures, which drive cost efficiency for SaaS solution providers, limit customization of applications for large clients, inhibiting such applications from being used in scenarios (applicable mostly to large enterprises) for which such customization is necessary.

- Some business applications require access to or integration with customer's current data. When such data are large in volume or sensitive (e.g. end-users' personal information), integrating them with remotely hosted software can be costly or risky, or can conflict with data governance regulations.

- Constitutional search/seizure warrant laws do not protect all forms of SaaS dynamically stored data. The end result is that a link is added to the chain of security where access to the data, and, by extension, misuse of these data, are limited only by the assumed honesty of third parties or government agencies able to access the data on their own recognizance.

- Switching SaaS vendors may involve the slow and difficult task of transferring very large data files over the Internet.

- Organizations that adopt SaaS may find they are forced into adopting new versions, which might result in unforeseen training costs, an increase in the probability that a user might make an error or instability from bugs in the newer software.

- Should the vendor of the software go out of business or suddenly EOL the software, the user may lose access to their software unexpectedly, which could destabilize their organization's current and future projects, as well as leave the user with older data they can no longer access or modify.

- Relying on an Internet connection means that data is transferred to and from a SaaS firm at Internet speeds, rather than the potentially higher speeds of a firm's internal network.

- Can the SaaS hosting company guarantee the uptime level agreed in the SLA (service level agreement)?

The standard model also has limitations:

- Compatibility with hardware, other software, and operating systems.

- Licensing and compliance problems (unauthorized copies of the software program putting the organization at risk of fines or litigation).

- Maintenance, support, and patch revision processes.

Healthcare applications

According

to a survey by HIMSS Analytics, 83% of US IT healthcare organizations

are now using cloud services with 9.3% planning to, whereas 67% of IT

healthcare organizations are currently running SaaS-based applications.

Data escrow

Software as a service data escrow

is the process of keeping a copy of critical software-as-a-service

application data with an independent third party. Similar to source code escrow, where critical software source code

is stored with an independent third party, SaaS data escrow applies the

same logic to the data within a SaaS application. It allows companies

to protect and insure all the data that resides within SaaS

applications, protecting against data loss.

There are many and varied reasons for considering SaaS data escrow including concerns about vendor bankruptcy, unplanned service outages, and potential data loss or corruption.

Many businesses either ensure that they are complying with their data governance standards or try to enhance their reporting and business analytics

against their SaaS data. A research conducted by Clearpace Software

Ltd. into the growth of SaaS showed that 85 percent of the participants

wanted to take a copy of their SaaS data. A third of these participants

wanted a copy on a daily basis.

Criticism

One notable criticism of SaaS comes from Richard Stallman of the Free Software Foundation, who refers to it as service as a software substitute (SaaSS). He considers the use of SaaSS to be a violation of the principles of free software. According to Stallman:

With SaaSS, the users do not have even the executable file that does their computing: it is on someone else's server, where the users can't see or touch it. Thus it is impossible for them to ascertain what it really does, and impossible to change it.

Not all SaaS products face this problem. In 2010, Forbes contributor Dan Woods noted that Drupal Gardens, a web hosting platform based on the open source Drupal content management system, is a "new open-source model for SaaS". He added:

Open source provides the escape hatch. In Drupal Gardens, users will be able to press a button and get a source code version of the Drupal code that runs their site along with the data from the database. Then, you can take that code, put it up at one of the hosting companies, and you can do anything that you would like to do.

Similarly, MediaWiki, WordPress

and their many extensions are increasingly used for a wide variety of

internal applications as well as public web services. Obtaining the

code is relatively simple, as it is an integration of existing

extensions, plug-ins, templates, etc. Actual customizations are rare,

and usually quickly replaced by more standard publicly available

extensions. There is additionally no guarantee the software source code

obtained through such means accurately reflects the software system it

claims to reflect.

Andrew Hoppin, a former Chief Information Officer for the New York State Senate, refers to this combination of SaaS and open source software as OpenSaaS and points to WordPress

as another successful example of an OpenSaaS software delivery model

that gives customers "the best of both worlds, and more options. The

fact that it is open source means that they can start building their

websites by self-hosting WordPress and customizing their website to

their heart’s content. Concurrently, the fact that WordPress is SaaS

means that they don’t have to manage the website at all – they can

simply pay WordPress.com to host it."[48]

The cloud (or SaaS) model has no physical need for indirect

distribution because it is not distributed physically and is deployed

almost instantaneously, thereby negating the need for traditional

partners and middlemen.