From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Determinism is the

philosophical

view that all events are determined completely by previously existing

causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have

sprung from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and

considerations. The opposite of determinism is some kind of

indeterminism (otherwise called nondeterminism) or

randomness. Determinism is often contrasted with

free will.

Determinism often is taken to mean causal determinism, which in physics is known as cause-and-effect. It is the concept that events within a given paradigm are bound by causality

in such a way that any state (of an object or event) is completely

determined by prior states. This meaning can be distinguished from other

varieties of determinism mentioned below.

Other debates often concern the scope of determined systems, with

some maintaining that the entire universe is a single determinate

system and others identifying other more limited determinate systems (or

multiverse).

Numerous historical debates involve many philosophical positions and

varieties of determinism. They include debates concerning determinism

and free will, technically denoted as compatibilistic (allowing the two to coexist) and incompatibilistic (denying their coexistence is a possibility). Determinism should not be confused with self-determination of human actions by reasons, motives, and desires. Determinism rarely requires that perfect prediction be practically possible.

Varieties

"Determinism" may commonly refer to any of the following viewpoints.

Causal determinism

Causal determinism, sometimes synonymous with historical determinism (a sort of path dependence), is "the idea that every event is necessitated by antecedent events and conditions together with the laws of nature." However, it is a broad enough term to consider that:

...one's

deliberations, choices, and actions will often be necessary links in

the causal chain that brings something about. In other words, even

though our deliberations, choices, and actions are themselves determined

like everything else, it is still the case, according to causal

determinism, that the occurrence or existence of yet other things

depends upon our deliberating, choosing and acting in a certain way.

Causal

determinism proposes that there is an unbroken chain of prior

occurrences stretching back to the origin of the universe. The relation

between events may not be specified, nor the origin of that universe.

Causal determinists believe that there is nothing in the universe that

is uncaused or self-caused.

Causal determinism has also been considered more generally as the idea

that everything that happens or exists is caused by antecedent

conditions.

In the case of nomological determinism, these conditions are considered

events also, implying that the future is determined completely by

preceding events—a combination of prior states of the universe and the

laws of nature. Yet they can also be considered metaphysical of origin (such as in the case of theological determinism).

Many philosophical theories of determinism frame themselves with the idea that reality follows a sort of predetermined path.

Nomological determinism

Nomological determinism, generally synonymous with physical determinism (its opposite being physical indeterminism),

the most common form of causal determinism, is the notion that the past

and the present dictate the future entirely and necessarily by rigid

natural laws, that every occurrence results inevitably from prior

events. Nomological determinism is sometimes illustrated by the thought experiment of Laplace's demon. Nomological determinism is sometimes called scientific determinism, although that is a misnomer.

Necessitarianism

Necessitarianism is closely related to the causal determinism described above. It is a metaphysical principle that denies all mere possibility; there is exactly one way for the world to be. Leucippus claimed there were no uncaused events, and that everything occurs for a reason and by necessity.

Predeterminism

Predeterminism is the idea that all events are determined in advance. The concept is often argued by invoking causal determinism, implying that there is an unbroken chain of prior occurrences

stretching back to the origin of the universe. In the case of

predeterminism, this chain of events has been pre-established, and human

actions cannot interfere with the outcomes of this pre-established

chain.

Predeterminism can be used to mean such pre-established causal

determinism, in which case it is categorised as a specific type of

determinism. It can also be used interchangeably with causal determinism—in the context of its capacity to determine future events. Despite this, predeterminism is often considered as independent of causal determinism.

Biological determinism

The term predeterminism is also frequently used in the context of biology and heredity, in which case it represents a form of biological determinism, sometimes called genetic determinism. Biological determinism is the idea that each of human behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by human genetic nature.

Fatalism

Fatalism is normally distinguished from "determinism",

as a form of teleological determinism. Fatalism is the idea that

everything is fated to happen, so that humans have no control over their

future. Fate has arbitrary power, and need not follow any causal or otherwise deterministic laws. Types of fatalism include hard theological determinism and the idea of predestination, where there is a God who determines all that humans will do. This may be accomplished either by knowing their actions in advance, via some form of omniscience or by decreeing their actions in advance.

Theological determinism

Theological determinism is a form of determinism that holds that all events that happen are either preordained (i.e., predestined) to happen by a monotheistic deity, or are destined to occur given its omniscience. Two forms of theological determinism exist, referred to as strong and weak theological determinism.

Strong theological determinism is based on the concept of a creator deity

dictating all events in history: "everything that happens has been

predestined to happen by an omniscient, omnipotent divinity."

Weak theological determinism is based on the concept of divine foreknowledge—"because God's

omniscience is perfect, what God knows about the future will inevitably

happen, which means, consequently, that the future is already fixed."

There exist slight variations on the this categorisation, however. Some

claim either that theological determinism requires predestination of

all events and outcomes by the divinity—i.e., they do not classify the

weaker version as theological determinism unless libertarian free will is assumed to be denied as a consequence—or that the weaker version does not constitute theological determinism at all.

With respect to free will, "theological determinism is the thesis

that God exists and has infallible knowledge of all true propositions

including propositions about our future actions," more minimal criteria

designed to encapsulate all forms of theological determinism.

Theological determinism can also be seen as a form of causal

determinism, in which the antecedent conditions are the nature and will

of God. Some have asserted that Augustine of Hippo

introduced theological determinism into Christianity in 412 CE, whereas

all prior Christian authors supported free will against Stoic and

Gnostic determinism. However, there are many Biblical passages that seem to support the idea of some kind of theological determinism including Psalm 115:3, Acts 2:23, and Lamentations 2:17.

Logical determinism

Adequate determinism focuses on

the fact that, even without a full understanding of microscopic physics, we can predict the distribution of 1000 coin tosses.

Logical determinism, or determinateness, is the notion that all propositions, whether about the past, present, or future, are either true or false.

Note that one can support causal determinism without necessarily

supporting logical determinism and vice versa (depending on one's views

on the nature of time, but also randomness).

The problem of free will is especially salient now with logical

determinism: how can choices be free, given that propositions about the

future already have a truth value in the present (i.e. it is already

determined as either true or false)? This is referred to as the problem of future contingents.

Often synonymous with logical determinism are the ideas behind spatio-temporal determinism or eternalism: the view of special relativity. J. J. C. Smart, a proponent of this view, uses the term tenselessness to describe the simultaneous existence of past, present, and future. In physics, the "block universe" of Hermann Minkowski and Albert Einstein

assumes that time is a fourth dimension (like the three spatial

dimensions). In other words, all the other parts of time are real, like

the city blocks up and down a street, although the order in which they

appear depends on the driver (see Rietdijk–Putnam argument).

Adequate determinism

Adequate determinism is the idea, because of quantum decoherence, that quantum indeterminacy can be ignored for most macroscopic events. Random quantum events "average out" in the limit of large numbers of particles (where the laws of quantum mechanics asymptotically approach the laws of classical mechanics). Stephen Hawking explains a similar idea: he says that the microscopic world of quantum mechanics is one of determined probabilities. That is, quantum effects rarely alter the predictions of classical mechanics, which are quite accurate (albeit still not perfectly certain) at larger scales. Something as large as an animal cell, then, would be "adequately determined" (even in light of quantum indeterminacy).

Many-worlds

The many-worlds interpretation

accepts the linear causal sets of sequential events with adequate

consistency yet also suggests constant forking of causal chains creating

"multiple universes" to account for multiple outcomes from single

events.

Meaning the causal set of events leading to the present are all valid

yet appear as a singular linear time stream within a much broader unseen

conic probability field of other outcomes that "split off" from the

locally observed timeline. Under this model causal sets are still

"consistent" yet not exclusive to singular iterated outcomes.

The interpretation side steps the exclusive retrospective causal

chain problem of "could not have done otherwise" by suggesting "the

other outcome does exist" in a set of parallel universe time streams

that split off when the action occurred. This theory is sometimes

described with the example of agent based choices but more involved

models argue that recursive causal splitting occurs with all particle

wave functions at play. This model is highly contested with multiple objections from the scientific community.

Philosophical varieties

Determinism in nature/nurture controversy

Nature

and nurture interact in humans. A scientist looking at a sculpture

after some time does not ask whether we are seeing the effects of the

starting materials or of environmental influences.

Although some of the above forms of determinism concern human behaviors and cognition, others frame themselves as an answer to the debate on nature and nurture.

They will suggest that one factor will entirely determine behavior. As

scientific understanding has grown, however, the strongest versions of

these theories have been widely rejected as a single-cause fallacy. In other words, the modern deterministic theories attempt to explain how the interaction of both nature and nurture is entirely predictable. The concept of heritability has been helpful in making this distinction.

- Biological determinism, sometimes called genetic determinism, is the idea that each of human behaviors, beliefs, and desires are fixed by human genetic nature.

- Behaviorism involves the idea that all behavior can be traced to specific causes—either environmental or reflexive. John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner developed this nurture-focused determinism.

- Cultural determinism, along with social determinism, is the nurture-focused theory that the culture in which we are raised determines who we are.

- Environmental determinism, also known as climatic or geographical determinism,

proposes that the physical environment, rather than social conditions,

determines culture. Supporters of environmental determinism often[quantify] also support Behavioral determinism. Key proponents of this notion have included Ellen Churchill Semple, Ellsworth Huntington, Thomas Griffith Taylor and possibly Jared Diamond, although his status as an environmental determinist is debated.

Determinism and prediction

A

technological determinist might suggest that technology like the mobile

phone is the greatest factor shaping human civilization.

Other 'deterministic' theories actually seek only to highlight the

importance of a particular factor in predicting the future. These

theories often use the factor as a sort of guide or constraint on the

future. They need not suppose that complete knowledge of that one factor

would allow us to make perfect predictions.

Structural determinism

Philosophy

has explored the concept of determinism for thousands of years, which

derives from the principle of causality. But philosophers, often, do not

clearly distinguish between cosmic nature, human nature, and historical

reality. Anthropologists define historical reality as synonymous with

culture. The reality of determinism, as an uncontrollable element for

human beings, unfolds in the classification of various types of society,

after the overcoming of the "society of nature", identifiable with the

overcoming of the society without any structure (and, therefore,

consistent with the nature of the animal species, endowed with a minimum

sociality, and minimal psychic processing). On the contrary, structured

societies are based on cultural mechanisms, that is to say on

mechanisms other than natural drives, which drives are common to all

social animals. Already for some animal species, with less intellectual

capacity than homo sapiens, elements of structures can be noted, that

is, elements of the societies of the hordes, or of the tribal societies

or those with stable social stratifications. These structural elements,

insofar as they are artificial, or extraneous to the nature of the

specific species in which they emerge, constitute factors of external

determination, that is, of upheaval, on the drives, desires, needs, and

purposes of the individuals of that particular species.

Contemporary human beings are generally inserted in a social

reality equipped with structures, of an organic-stratified type, based

on the concept and essence of the state, and therefore definable as

structural statual reality, suffer from this reality structural, a

decisive influence, which is such as to determine, almost entirely,

their character, their thinking, and their behavior.

Of this decisive influence, human beings are very little, or not at all,

conscious, and can realize such consciousness only through in-depth

philosophical studies, and individual reflections. Individually, they

can, at least partially, abstract themselves from this decisive

influence, only if they self-marginalize themselves from the reality of

these same structures, in the specific manifestation that the latter

assumption, in the historical era in which a specific individual finds

himself living. This marginalization does not necessarily imply social

isolation, which causes it to take refuge in asociality, but to renounce

being actively involved in the logic of the specific historical moment

in which the individual finds himself living and, therefore, even more,

abstracting from the hierarchical logic, based on the principle of

authority, which is characteristic of the structural reality,

historically determined and, in turn, decisive, on the individuals and

peoples.

With free will

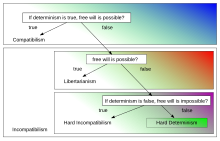

A simplified

taxonomy of philosophical positions regarding free will and determinism.

Philosophers have debated both the truth of determinism, and the

truth of free will. This creates the four possible positions in the

figure. Compatibilism refers to the view that free will is, in some sense, compatible with determinism. The three incompatibilist positions, on the other hand, deny this possibility. The hard incompatibilists hold that free will is incompatible with both determinism and indeterminism, the libertarianists that determinism does not hold, and free will might exist, and the hard determinists that determinism does hold and free will does not exist.

The Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza

was a determinist thinker, and argued that human freedom can be

achieved through knowledge of the causes that determine our desire and

affections. He defined human servitude as the state of bondage of the

man who is aware of his own desires, but ignorant of the causes that

determined him. On the other hand, the free or virtuous man becomes

capable, through reason and knowledge, to be genuinely free, even as he

is being "determined". For the Dutch philosopher, acting out of our own

internal necessity is genuine freedom

while being driven by exterior determinations is akin to bondage.

Spinoza's thoughts on human servitude and liberty are respectively

detailed in the fourth and fifth volumes of his work Ethics.

The standard argument against free will, according to philosopher J. J. C. Smart, focuses on the implications of determinism for 'free will'.

However, he suggests free will is denied whether determinism is true or

not. On one hand, if determinism is true, all our actions are predicted

and we are assumed not to be free; on the other hand, if determinism is

false, our actions are presumed to be random and as such we do not seem

free because we had no part in controlling what happened.

With the soul

Some determinists argue that materialism

does not present a complete understanding of the universe, because

while it can describe determinate interactions among material things, it

ignores the minds or souls of conscious beings.

A number of positions can be delineated:

- Immaterial souls are all that exist (idealism).

- Immaterial souls exist and exert a non-deterministic causal influence on bodies (traditional free-will, interactionist dualism).

- Immaterial souls exist, but are part of a deterministic framework.

- Immaterial souls exist, but exert no causal influence, free or determined (epiphenomenalism, occasionalism)

- Immaterial souls do not exist – there is no mind-body dichotomy, and there is a materialistic explanation for intuitions to the contrary.

With ethics and morality

Another topic of debate is the implication that Determinism has on morality. Hard determinism

(a belief in determinism, and not free will) is particularly criticized

for seeming to make traditional moral judgments impossible. Some

philosophers find this an acceptable conclusion.

Philosopher and incompatibilist Peter van Inwagen introduces this thesi, when argument that free will is required for moral judgments, as such:

- The moral judgment that X should not have been done implies that something else should have been done instead

- That something else should have been done instead implies that there was something else to do

- That there was something else to do implies that something else could have been done

- That something else could have been done implies that there is free will

- If there is no free will to have done other than X we cannot make the moral judgment that X should not have been done.

However, a compatibilist might have an issue with Inwagen's process,

because one cannot change the past as their arguments center around. A

compatibilist who centers around plans for the future might posit:

- The moral judgment that X should not have been done implies that something else could have been done instead

- That something else can be done instead implies that there is something else to do

- That there is something else to do implies that something else can be done

- That something else can be done implies that there is free will for planning future recourse

- If there is free will to do other than X the moral judgment can be made that other than X should be done, a responsible party for having done X while knowing it should not have been done should be punished to help remember to not do X in the future.

History

Determinism was developed by the Greek philosophers during the 7th and 6th centuries BC by the Pre-socratic philosophers Heraclitus and Leucippus, later Aristotle, and mainly by the Stoics. Some of the main philosophers who have dealt with this issue are Marcus Aurelius, Omar Khayyám, Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Gottfried Leibniz, David Hume, Baron d'Holbach (Paul Heinrich Dietrich), Pierre-Simon Laplace, Arthur Schopenhauer, William James, Friedrich Nietzsche, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Ralph Waldo Emerson and, more recently, John Searle, Ted Honderich, and Daniel Dennett.

Mecca Chiesa notes that the probabilistic or selectionistic determinism of B. F. Skinner comprised a wholly separate conception of determinism that was not mechanistic

at all. Mechanistic determinism assumes that every event has an

unbroken chain of prior occurrences, but a selectionistic or

probabilistic model does not.

Western tradition

In the West, some elements of determinism have been expressed in Greece from the 6th century BC by the Presocratics Heraclitus and Leucippus. The first full-fledged notion of determinism appears to originate with the Stoics, as part of their theory of universal causal determinism.

The resulting philosophical debates, which involved the confluence of

elements of Aristotelian Ethics with Stoic psychology, led in the

1st-3rd centuries CE in the works of Alexander of Aphrodisias to the first recorded Western debate over determinism and freedom, an issue that is known in theology as the paradox of free will. The writings of Epictetus as well as middle Platonist and early Christian thought were instrumental in this development. Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides said of the deterministic implications of an omniscient god:

"Does God know or does He not know that a certain individual will be

good or bad? If thou sayest 'He knows', then it necessarily follows that

[that] man is compelled to act as God knew beforehand he would act,

otherwise God's knowledge would be imperfect."

Newtonian mechanics

Determinism in the West is often associated with Newtonian mechanics/physics,

which depicts the physical matter of the universe as operating

according to a set of fixed, knowable laws. The "billiard ball"

hypothesis, a product of Newtonian physics, argues that once the initial

conditions of the universe have been established, the rest of the

history of the universe follows inevitably. If it were actually possible

to have complete knowledge of physical matter and all of the laws

governing that matter at any one time, then it would be theoretically

possible to compute the time and place of every event that will ever

occur (Laplace's demon).

In this sense, the basic particles of the universe operate in the same

fashion as the rolling balls on a billiard table, moving and striking

each other in predictable ways to produce predictable results.

Whether or not it is all-encompassing in so doing, Newtonian

mechanics deals only with caused events; for example, if an object

begins in a known position and is hit dead on by an object with some

known velocity, then it will be pushed straight toward another

predictable point. If it goes somewhere else, the Newtonians argue, one

must question one's measurements of the original position of the object,

the exact direction of the striking object, gravitational or other

fields that were inadvertently ignored, etc. Then, they maintain,

repeated experiments and improvements in accuracy will always bring

one's observations closer to the theoretically predicted results. When

dealing with situations on an ordinary human scale, Newtonian physics

has been so enormously successful that it has no competition. But it

fails spectacularly as velocities become some substantial fraction of

the speed of light and when interactions at the atomic scale are studied. Before the discovery of quantum

effects and other challenges to Newtonian physics, "uncertainty" was

always a term that applied to the accuracy of human knowledge about

causes and effects, and not to the causes and effects themselves.

Newtonian mechanics, as well as any following physical theories,

are results of observations and experiments, and so they describe "how

it all works" within a tolerance. However, old western scientists

believed if there are any logical connections found between an observed

cause and effect, there must be also some absolute natural laws behind.

Belief in perfect natural laws driving everything, instead of just

describing what we should expect, led to searching for a set of

universal simple laws that rule the world. This movement significantly

encouraged deterministic views in Western philosophy, as well as the related theological views of classical pantheism.

Eastern tradition

The idea that the entire universe is a deterministic system has been articulated in both Eastern and non-Eastern religion, philosophy, and literature.

In I Ching and Philosophical Taoism, the ebb and flow of favorable and unfavorable conditions suggests the path of least resistance is effortless (see Wu wei).

In the philosophical schools of the Indian Subcontinent, the concept of karma

deals with similar philosophical issues to the western concept of

determinism. Karma is understood as a spiritual mechanism which causes

the entire cycle of rebirth (i.e. Saṃsāra).

Karma, either positive or negative, accumulates according to an

individual's actions throughout their life, and at their death

determines the nature of their next life in the cycle of Saṃsāra. Most

major religions originating in India hold this belief to some degree,

most notably Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism, and Buddhism.

The views on the interaction of karma and free will are numerous, and diverge from each other greatly. For example, in Sikhism,

God's grace, gained through worship, can erase one's karmic debts, a

belief which reconciles the principle of Karma with a monotheistic God

one must freely choose to worship. Jainism, on the other hand, believe in a sort of compatibilism,

in which the cycle of Saṃsara is a completely mechanistic process,

occurring without any divine intervention. The Jains hold an atomic view

of reality, in which particles of karma form the fundamental

microscopic building material of the universe, resembling in some ways

modern-day atomic theory.

Buddhism

Buddhist

philosophy contains several concepts which some scholars describe as

deterministic to various levels. However, the direct analysis of

Buddhist metaphysics through the lens of determinism is difficult, due

to the differences between European and Buddhist traditions of thought.

One concept which is argued to support a hard determinism is the idea of dependent origination, which claims that all phenomena (dharma) are necessarily caused by some other phenomenon, which it can be said to be dependent

on, like links in a massive chain. In traditional Buddhist philosophy,

this concept is used to explain the functioning of the cycle of saṃsāra;

all actions exert a karmic force, which will manifest results in future

lives. In other words, righteous or unrighteous actions in one life

will necessarily cause good or bad responses in another.

Another Buddhist concept which many scholars perceive to be deterministic is the idea of non-self, or anatta. In Buddhism, attaining enlightenment

involves one realizing that in humans there is no fundamental core of

being which can be called the "soul", and that humans are instead made

of several constantly changing factors which bind them to the cycle of Saṃsāra.

Some scholars argue that the concept of non-self necessarily

disproves the ideas of free will and moral culpability. If there is no

autonomous self, in this view, and all events are necessarily and

unchangeably caused by others, then no type of autonomy can be said to

exist, moral or otherwise. However, other scholars disagree, claiming

that the Buddhist conception of the universe allows for a form of

compatibilism. Buddhism perceives reality occurring on two different

levels, the ultimate reality which can only be truly understood by the

enlightened, and the illusory

and false material reality. Therefore, Buddhism perceives free will as a

notion belonging to material reality, while concepts like non-self and

dependent origination belong to the ultimate reality; the transition

between the two can be truly understood, Buddhists claim, by one who has

attained enlightenment.

Modern scientific perspective

Generative processes

Although it was once thought by scientists that any indeterminism in

quantum mechanics occurred at too small a scale to influence biological

or neurological systems, there is indication that nervous systems are influenced by quantum indeterminism due to chaos theory. It is unclear what implications this has for the problem of free will given various possible reactions to the problem in the first place.

Many biologists do not grant determinism: Christof Koch, for instance, argues against it, and in favour of libertarian free will, by making arguments based on generative processes (emergence). Other proponents of emergentist or generative philosophy, cognitive sciences, and evolutionary psychology, argue that a certain form of determinism (not necessarily causal) is true.

They suggest instead that an illusion of free will is experienced due

to the generation of infinite behaviour from the interaction of

finite-deterministic set of rules and parameters.

Thus the unpredictability of the emerging behaviour from deterministic

processes leads to a perception of free will, even though free will as

an ontological entity does not exist.

In

Conway's Game of Life, the interaction of just four simple rules creates patterns that seem somehow "alive".

As an illustration, the strategy board-games chess and Go have rigorous rules in which no information (such as cards' face-values) is hidden from either player and no random

events (such as dice-rolling) happen within the game. Yet, chess and

especially Go with its extremely simple deterministic rules, can still

have an extremely large number of unpredictable moves. When chess is

simplified to 7 or fewer pieces, however, endgame tables are available

that dictate which moves to play to achieve a perfect game. This

implies that, given a less complex environment (with the original 32

pieces reduced to 7 or fewer pieces), a perfectly predictable game of

chess is possible. In this scenario, the winning player can announce

that a checkmate will happen within a given number of moves, assuming a

perfect defense by the losing player, or fewer moves if the defending

player chooses sub-optimal moves as the game progresses into its

inevitable, predicted conclusion. By this analogy, it is suggested, the

experience of free will emerges from the interaction of finite rules and

deterministic parameters that generate nearly infinite and practically

unpredictable behavioural responses. In theory, if all these events

could be accounted for, and there were a known way to evaluate these

events, the seemingly unpredictable behaviour would become predictable. Another hands-on example of generative processes is John Horton Conway's playable Game of Life. Nassim Taleb is wary of such models, and coined the term "ludic fallacy."

Compatibility with the existence of science

Certain philosophers of science

argue that, while causal determinism (in which everything including the

brain/mind is subject to the laws of causality) is compatible with

minds capable of science, fatalism and predestination is not. These

philosophers make the distinction that causal determinism means that

each step is determined by the step before and therefore allows sensory

input from observational data to determine what conclusions the brain

reaches, while fatalism in which the steps between do not connect an

initial cause to the results would make it impossible for observational

data to correct false hypotheses. This is often combined with the

argument that if the brain had fixed views and the arguments were mere

after-constructs with no causal effect on the conclusions, science would

have been impossible and the use of arguments would have been a

meaningless waste of energy with no persuasive effect on brains with

fixed views.

Mathematical models

Many mathematical models of physical systems are deterministic. This is true of most models involving differential equations

(notably, those measuring rate of change over time). Mathematical

models that are not deterministic because they involve randomness are

called stochastic. Because of sensitive dependence on initial conditions,

some deterministic models may appear to behave non-deterministically;

in such cases, a deterministic interpretation of the model may not be

useful due to numerical instability and a finite amount of precision

in measurement. Such considerations can motivate the consideration of a

stochastic model even though the underlying system is governed by

deterministic equations.

Quantum and classical mechanics

Day-to-day physics

Since the beginning of the 20th century, quantum mechanics—the physics of the extremely small—has revealed previously concealed aspects of events. Before that, Newtonian physics—the physics of everyday life—dominated. Taken in isolation (rather than as an approximation

to quantum mechanics), Newtonian physics depicts a universe in which

objects move in perfectly determined ways. At the scale where humans

exist and interact with the universe, Newtonian mechanics remain useful,

and make relatively accurate predictions (e.g. calculating the

trajectory of a bullet). But whereas in theory, absolute knowledge

of the forces accelerating a bullet would produce an absolutely

accurate prediction of its path, modern quantum mechanics casts

reasonable doubt on this main thesis of determinism.

Relevant is the fact that certainty is never absolute in practice (and not just because of David Hume's problem of induction). The equations of Newtonian mechanics can exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions. This is an example of the butterfly effect, which is one of the subjects of chaos theory.

The idea is that something even as small as a butterfly could cause a

chain reaction leading to a hurricane years later. Consequently, even a

very small error in knowledge of initial conditions can result in

arbitrarily large deviations from predicted behavior. Chaos theory thus

explains why it may be practically impossible to predict real life, whether determinism is true or false. On the other hand, the issue may not be so much about human abilities to predict or attain certainty as much as it is the nature of reality itself. For that, a closer, scientific look at nature is necessary.

Quantum realm

Quantum physics works differently in many ways from Newtonian physics. Physicist Aaron D. O'Connell explains that understanding our universe, at such small scales as atoms,

requires a different logic than day-to-day life does. O'Connell does

not deny that it is all interconnected: the scale of human existence

ultimately does emerge from the quantum scale. O'Connell argues that we

must simply use different models and constructs when dealing with the

quantum world. Quantum mechanics is the product of a careful application of the scientific method, logic and empiricism. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is frequently confused with the observer effect. The uncertainty principle actually describes how precisely we may measure the position and momentum

of a particle at the same time – if we increase the accuracy in

measuring one quantity, we are forced to lose accuracy in measuring the

other. "These uncertainty relations give us that measure of freedom from

the limitations of classical concepts which is necessary for a

consistent description of atomic processes."

Although

it is not possible to predict the trajectory of any one particle, they

all obey determined probabilities which do permit some prediction

This is where statistical mechanics

come into play, and where physicists begin to require rather

unintuitive mental models: A particle's path simply cannot be exactly

specified in its full quantum description. "Path" is a classical,

practical attribute in our everyday life, but one that quantum particles

do not meaningfully possess. The probabilities discovered in quantum

mechanics do nevertheless arise from measurement (of the perceived path

of the particle). As Stephen Hawking explains, the result is not traditional determinism, but rather determined probabilities.

In some cases, a quantum particle may indeed trace an exact path, and

the probability of finding the particles in that path is one (certain to

be true). In fact, as far as prediction goes, the quantum development

is at least as predictable as the classical motion, but the key is that

it describes wave functions

that cannot be easily expressed in ordinary language. As far as the

thesis of determinism is concerned, these probabilities, at least, are

quite determined. These findings from quantum mechanics have found many applications, and allow us to build transistors and lasers.

Put another way: personal computers, Blu-ray players and the Internet

all work because humankind discovered the determined probabilities of

the quantum world. None of that should be taken to imply that other aspects of quantum mechanics are not still up for debate.

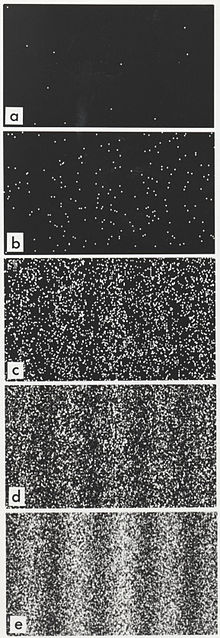

On the topic of predictable probabilities, the double-slit experiments are a popular example. Photons

are fired one-by-one through a double-slit apparatus at a distant

screen. They do not arrive at any single point, nor even the two points

lined up with the slits (the way it might be expected of bullets fired

by a fixed gun at a distant target). Instead, the light arrives in

varying concentrations at widely separated points, and the distribution

of its collisions with the target can be calculated reliably. In that

sense the behavior of light in this apparatus is deterministic, but

there is no way to predict where in the resulting interference pattern any individual photon will make its contribution (although, there may be ways to use weak measurement to acquire more information without violating the uncertainty principle).

Some (including Albert Einstein) argue that our inability to predict any more than probabilities is simply due to ignorance. The idea is that, beyond the conditions and laws we can observe or deduce, there are also hidden factors or "hidden variables" that determine absolutely

in which order photons reach the detector screen. They argue that the

course of the universe is absolutely determined, but that humans are

screened from knowledge of the determinative factors. So, they say, it

only appears that things proceed in a merely probabilistically

determinative way. In actuality, they proceed in an absolutely

deterministic way.

John S. Bell criticized Einstein's work in his famous Bell's theorem,

which proved that quantum mechanics can make statistical predictions

that would be violated if local hidden variables really existed. A

number of experiments have tried to verify such predictions, and so far

they do not appear to be violated. Current experiments continue to

verify the result, including the 2015 "Loophole Free Test" that plugged all known sources of error and the 2017 "Cosmic Bell Test"

experiment that used cosmic data streaming from different directions

toward the Earth, precluding the possibility the sources of data could

have had prior interactions. However, it is possible to augment quantum

mechanics with non-local hidden variables to achieve a deterministic

theory that is in agreement with experiment. An example is the Bohm interpretation

of quantum mechanics. Bohm's Interpretation, though, violates special

relativity and it is highly controversial whether or not it can be

reconciled without giving up on determinism.

More advanced variations on these arguments include Quantum contextuality, by Bell, Simon B. Kochen and Ernst Specker,

which argues that hidden variable theories cannot be "sensible,"

meaning that the values of the hidden variables inherently depend on the

devices used to measure them.

This debate is relevant because it is easy to imagine specific

situations in which the arrival of an electron at a screen at a certain

point and time would trigger one event, whereas its arrival at another

point would trigger an entirely different event (e.g. see Schrödinger's cat - a thought experiment used as part of a deeper debate).

Thus, quantum physics casts reasonable doubt on the traditional

determinism of classical, Newtonian physics in so far as reality does

not seem to be absolutely determined. This was the subject of the famous

Bohr–Einstein debates between Einstein and Niels Bohr and there is still no consensus.

Adequate determinism (see Varieties, above) is the reason that Stephen Hawking calls Libertarian free will "just an illusion".

Other matters of quantum determinism

Chaotic radioactivity is the next explanatory challenge for physicists supporting determinism.

All uranium found on earth is thought to have been synthesized during a supernova

explosion that occurred roughly 5 billion years ago. Even before the

laws of quantum mechanics were developed to their present level, the radioactivity of such elements has posed a challenge to determinism due to its unpredictability. One gram of uranium-238, a commonly occurring radioactive substance, contains some 2.5 x 1021

atoms. Each of these atoms are identical and indistinguishable

according to all tests known to modern science. Yet about 12600 times a

second, one of the atoms in that gram will decay, giving off an alpha particle.

The challenge for determinism is to explain why and when decay occurs,

since it does not seem to depend on external stimulus. Indeed, no extant

theory of physics makes testable

predictions of exactly when any given atom will decay. At best

scientists can discover determined probabilities in the form of the

element's half life.

The time dependent Schrödinger equation gives the first time derivative of the quantum state. That is, it explicitly and uniquely predicts the development of the wave function with time.

So if the wave function itself is reality (rather than probability of

classical coordinates), then the unitary evolution of the wave function

in quantum mechanics, can be said to be deterministic. But the unitary

evolution of the wave function is not the entirety of quantum mechanics.

Asserting that quantum mechanics is deterministic by treating the wave function itself as reality might be thought to imply a single wave function for the entire universe,

starting at the origin of the universe. Such a "wave function of

everything" would carry the probabilities of not just the world we know,

but every other possible world that could have evolved. For example,

large voids in the distributions of galaxies are believed by many cosmologists to have originated in quantum fluctuations during the big bang. (See cosmic inflation, primordial fluctuations and large-scale structure of the cosmos.)

However, neither the posited reality nor the proven and

extraordinary accuracy of the wave function and quantum mechanics at

small scales can imply or reasonably suggest the existence of a single

wave function for the entire universe. Quantum mechanics breaks down

wherever gravity becomes significant, because nothing in the wave

function, or in quantum mechanics, predicts anything at all about

gravity. And this is obviously of great importance on larger scales.

Gravity is thought of as a large-scale force, with a longer reach

than any other. But gravity becomes significant even at masses that are

tiny compared to the mass of the universe.

A wave function the size of the universe might successfully model

a universe with no gravity. Our universe, with gravity, is vastly

different from what quantum mechanics alone predicts. To forget this is a

colossal error.

Objective collapse theories, which involve a dynamic (and non-deterministic) collapse of the wave function (e.g. Ghirardi–Rimini–Weber theory, Penrose interpretation, or causal fermion systems) avoid these absurdities. The theory of causal fermion systems for example, is able to unify quantum mechanics, general relativity and quantum field theory,

via a more fundamental theory that is non-linear, but gives rise to the

linear behaviour of the wave function and also gives rise to the

non-linear, non-deterministic, wave-function collapse. These theories

suggest that a deeper understanding of the theory underlying quantum

mechanics shows the universe is indeed non-deterministic at a

fundamental level.