| |

| Abbreviation | IMF |

|---|---|

| Formation | 27 December 1945 |

| Type | International financial institution |

| Purpose | Promote international monetary co-operation, facilitate international trade, foster sustainable economic growth, reduce poverty around the world, make resources available to members experiencing balance of payments difficulties, prevent and assist with recovery from international financial crises |

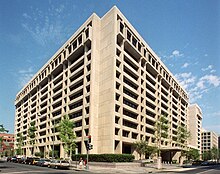

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′56″N 77°2′39″WCoordinates: 38°53′56″N 77°2′39″W |

Region | Worldwide |

Membership | 190 countries |

Official language | English |

Managing Director | Kristalina Georgieva |

Chief Economist | Gita Gopinath |

Main organ | Board of Governors |

Parent organization | United Nations |

Staff | 2,400 |

| Website | IMF.org |

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world while periodically depending on the World Bank for its resources. Formed in 1944 ,started in 27 November 1945, at the Bretton Woods Conference primarily by the ideas of Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, it came into formal existence in 1945 with 29 member countries and the goal of reconstructing the international monetary system. It now plays a central role in the management of balance of payments difficulties and international financial crises. Countries contribute funds to a pool through a quota system from which countries experiencing balance of payments problems can borrow money. As of 2016, the fund had XDR 477 billion (about US$667 billion).

Through the fund and other activities such as the gathering of statistics and analysis, surveillance of its members' economies, and the demand for particular policies, the IMF works to improve the economies of its member countries. The organization's objectives stated in the Articles of Agreement are: to promote international monetary co-operation, international trade, high employment, exchange-rate stability, sustainable economic growth, and making resources available to member countries in financial difficulty. IMF funds come from two major sources: quotas and loans. Quotas, which are pooled funds of member nations, generate most IMF funds. The size of a member's quota depends on its economic and financial importance in the world. Nations with greater economic significance have larger quotas. The quotas are increased periodically as a means of boosting the IMF's resources in the form of special drawing rights.

The current Managing Director (MD) and Chairwoman of the IMF is Bulgarian economist Kristalina Georgieva, who has held the post since October 1, 2019. Gita Gopinath was appointed as Chief Economist of IMF from 1 October 2018. Prior to her appointment at the IMF, Gopinath served as the economic adviser to the Chief Minister of Kerala, India.

Functions

According to the IMF itself, it works to foster global growth and economic stability by providing policy advice and financing the members by working with developing countries to help them achieve macroeconomic stability and reduce poverty. The rationale for this is that private international capital markets function imperfectly and many countries have limited access to financial markets. Such market imperfections, together with balance-of-payments financing, provide the justification for official financing, without which many countries could only correct large external payment imbalances through measures with adverse economic consequences. The IMF provides alternate sources of financing.

Upon the founding of the IMF, its three primary functions were: to oversee the fixed exchange rate arrangements between countries, thus helping national governments manage their exchange rates and allowing these governments to prioritize economic growth, and to provide short-term capital to aid the balance of payments. This assistance was meant to prevent the spread of international economic crises. The IMF was also intended to help mend the pieces of the international economy after the Great Depression and World War II as well as to provide capital investments for economic growth and projects such as infrastructure.

The IMF's role was fundamentally altered by the floating exchange rates post-1971. It shifted to examining the economic policies of countries with IMF loan agreements to determine if a shortage of capital was due to economic fluctuations or economic policy. The IMF also researched what types of government policy would ensure economic recovery. A particular concern of the IMF was to prevent financial crises such as those in Mexico in 1982, Brazil in 1987, East Asia in 1997–98, and Russia in 1998, from spreading and threatening the entire global financial and currency system. The challenge was to promote and implement policy that reduced the frequency of crises among the emerging market countries, especially the middle-income countries which are vulnerable to massive capital outflows. Rather than maintaining a position of oversight of only exchange rates, their function became one of surveillance of the overall macroeconomic performance of member countries. Their role became a lot more active because the IMF now manages economic policy rather than just exchange rates.

In addition, the IMF negotiates conditions on lending and loans under their policy of conditionality, which was established in the 1950s. Low-income countries can borrow on concessional terms, which means there is a period of time with no interest rates, through the Extended Credit Facility (ECF), the Standby Credit Facility (SCF) and the Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). Nonconcessional loans, which include interest rates, are provided mainly through the Stand-By Arrangements (SBA), the Flexible Credit Line (FCL), the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL), and the Extended Fund Facility. The IMF provides emergency assistance via the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) to members facing urgent balance-of-payments needs.

Surveillance of the global economy

The IMF is mandated to oversee the international monetary and financial system and monitor the economic and financial policies of its member countries. This activity is known as surveillance and facilitates international co-operation. Since the demise of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates in the early 1970s, surveillance has evolved largely by way of changes in procedures rather than through the adoption of new obligations. The responsibilities changed from those of guardian to those of overseer of members' policies.

The Fund typically analyses the appropriateness of each member country's economic and financial policies for achieving orderly economic growth, and assesses the consequences of these policies for other countries and for the global economy. The maximum sustainable debt level of a polity, which is watched closely by the IMF, was defined in 2011 by IMF economists to be 120%. Indeed, it was at this number that the Greek economy melted down in 2010.

In 1995 the International Monetary Fund began to work on data dissemination standards with the view of guiding IMF member countries to disseminate their economic and financial data to the public. The International Monetary and Financial Committee (IMFC) endorsed the guidelines for the dissemination standards and they were split into two tiers: The General Data Dissemination System (GDDS) and the Special Data Dissemination Standard (SDDS).

The executive board approved the SDDS and GDDS in 1996 and 1997 respectively, and subsequent amendments were published in a revised Guide to the General Data Dissemination System. The system is aimed primarily at statisticians and aims to improve many aspects of statistical systems in a country. It is also part of the World Bank Millennium Development Goals and Poverty Reduction Strategic Papers.

The primary objective of the GDDS is to encourage member countries to build a framework to improve data quality and statistical capacity building to evaluate statistical needs, set priorities in improving the timeliness, transparency, reliability and accessibility of financial and economic data. Some countries initially used the GDDS, but later upgraded to SDDS.

Some entities that are not themselves IMF members also contribute statistical data to the systems:

- Palestinian Authority – GDDS

- Hong Kong – SDDS

- Macau – GDDS

- Institutions of the European Union:

- the European Central Bank for the Eurozone – SDDS

- Eurostat for the whole EU – SDDS, thus providing data from Cyprus (not using any DDSystem on its own) and Malta (using only GDDS on its own)

Conditionality of loans

IMF conditionality is a set of policies or conditions that the IMF requires in exchange for financial resources. The IMF does require collateral from countries for loans but also requires the government seeking assistance to correct its macroeconomic imbalances in the form of policy reform. If the conditions are not met, the funds are withheld. The concept of conditionality was introduced in a 1952 Executive Board decision and later incorporated into the Articles of Agreement.

Conditionality is associated with economic theory as well as an enforcement mechanism for repayment. Stemming primarily from the work of Jacques Polak, the theoretical underpinning of conditionality was the "monetary approach to the balance of payments".

Structural adjustment

Some of the conditions for structural adjustment can include:

- Cutting expenditures or raising revenues, also known as austerity.

- Focusing economic output on direct export and resource extraction,

- Devaluation of currencies,

- Trade liberalisation, or lifting import and export restrictions,

- Increasing the stability of investment (by supplementing foreign direct investment with the opening of domestic stock markets),

- Balancing budgets and not overspending,

- Removing price controls and state subsidies,

- Privatization, or divestiture of all or part of state-owned enterprises,

- Enhancing the rights of foreign investors vis-a-vis national laws,

- Improving governance and fighting corruption.

These conditions are known as the Washington Consensus.

Benefits

These loan conditions ensure that the borrowing country will be able to repay the IMF and that the country will not attempt to solve their balance-of-payment problems in a way that would negatively impact the international economy. The incentive problem of moral hazard—when economic agents maximise their own utility to the detriment of others because they do not bear the full consequences of their actions—is mitigated through conditions rather than providing collateral; countries in need of IMF loans do not generally possess internationally valuable collateral anyway.

Conditionality also reassures the IMF that the funds lent to them will be used for the purposes defined by the Articles of Agreement and provides safeguards that country will be able to rectify its macroeconomic and structural imbalances. In the judgment of the IMF, the adoption by the member of certain corrective measures or policies will allow it to repay the IMF, thereby ensuring that the resources will be available to support other members.

As of 2004, borrowing countries have had a good track record for repaying credit extended under the IMF's regular lending facilities with full interest over the duration of the loan. This indicates that IMF lending does not impose a burden on creditor countries, as lending countries receive market-rate interest on most of their quota subscription, plus any of their own-currency subscriptions that are loaned out by the IMF, plus all of the reserve assets that they provide the IMF.

History

20th century

The IMF was originally laid out as a part of the Bretton Woods system exchange agreement in 1944. During the Great Depression, countries sharply raised barriers to trade in an attempt to improve their failing economies. This led to the devaluation of national currencies and a decline in world trade.

This breakdown in international monetary co-operation created a need for oversight. The representatives of 45 governments met at the Bretton Woods Conference in the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in the United States, to discuss a framework for postwar international economic co-operation and how to rebuild Europe.

There were two views on the role the IMF should assume as a global economic institution. American delegate Harry Dexter White foresaw an IMF that functioned more like a bank, making sure that borrowing states could repay their debts on time. Most of White's plan was incorporated into the final acts adopted at Bretton Woods. British economist John Maynard Keynes, on the other hand, imagined that the IMF would be a cooperative fund upon which member states could draw to maintain economic activity and employment through periodic crises. This view suggested an IMF that helped governments and to act as the United States government had during the New Deal to the great recession of the 1930s.

The IMF formally came into existence on 27 December 1945, when the first 29 countries ratified its Articles of Agreement. By the end of 1946 the IMF had grown to 39 members. On 1 March 1947, the IMF began its financial operations, and on 8 May France became the first country to borrow from it.

The IMF was one of the key organizations of the international economic system; its design allowed the system to balance the rebuilding of international capitalism with the maximisation of national economic sovereignty and human welfare, also known as embedded liberalism. The IMF's influence in the global economy steadily increased as it accumulated more members. The increase reflected in particular the attainment of political independence by many African countries and more recently the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union because most countries in the Soviet sphere of influence did not join the IMF.

The Bretton Woods exchange rate system prevailed until 1971, when the United States government suspended the convertibility of the US$ (and dollar reserves held by other governments) into gold. This is known as the Nixon Shock. The changes to the IMF articles of agreement reflecting these changes were ratified by the 1976 Jamaica Accords. Later in the 1970s, large commercial banks began lending to states because they were awash in cash deposited by oil exporters. The lending of the so-called money center banks led to the IMF changing its role in the 1980s after a world recession provoked a crisis that brought the IMF back into global financial governance.

21st century

The IMF provided two major lending packages in the early 2000s to Argentina (during the 1998–2002 Argentine great depression) and Uruguay (after the 2002 Uruguay banking crisis). However, by the mid-2000s, IMF lending was at its lowest share of world GDP since the 1970s.

In May 2010, the IMF participated, in 3:11 proportion, in the first Greek bailout that totalled €110 billion, to address the great accumulation of public debt, caused by continuing large public sector deficits. As part of the bailout, the Greek government agreed to adopt austerity measures that would reduce the deficit from 11% in 2009 to "well below 3%" in 2014. The bailout did not include debt restructuring measures such as a haircut, to the chagrin of the Swiss, Brazilian, Indian, Russian, and Argentinian Directors of the IMF, with the Greek authorities themselves (at the time, PM George Papandreou and Finance Minister Giorgos Papakonstantinou) ruling out a haircut.

A second bailout package of more than €100 billion was agreed over the course of a few months from October 2011, during which time Papandreou was forced from office. The so-called Troika, of which the IMF is part, are joint managers of this programme, which was approved by the Executive Directors of the IMF on 15 March 2012 for XDR 23.8 billion and saw private bondholders take a haircut of upwards of 50%. In the interval between May 2010 and February 2012 the private banks of Holland, France and Germany reduced exposure to Greek debt from €122 billion to €66 billion.

As of January 2012, the largest borrowers from the IMF in order were Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Romania, and Ukraine.

On 25 March 2013, a €10 billion international bailout of Cyprus was agreed by the Troika, at the cost to the Cypriots of its agreement: to close the country's second-largest bank; to impose a one-time bank deposit levy on Bank of Cyprus uninsured deposits. No insured deposit of €100k or less were to be affected under the terms of a novel bail-in scheme.

The topic of sovereign debt restructuring was taken up by the IMF in April 2013 for the first time since 2005, in a report entitled "Sovereign Debt Restructuring: Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund's Legal and Policy Framework". The paper, which was discussed by the board on 20 May, summarised the recent experiences in Greece, St Kitts and Nevis, Belize, and Jamaica. An explanatory interview with Deputy Director Hugh Bredenkamp was published a few days later, as was a deconstruction by Matina Stevis of the Wall Street Journal.

In the October 2013 Fiscal Monitor publication, the IMF suggested that a capital levy capable of reducing Euro-area government debt ratios to "end-2007 levels" would require a very high tax rate of about 10%.

The Fiscal Affairs department of the IMF, headed at the time by Acting Director Sanjeev Gupta, produced a January 2014 report entitled "Fiscal Policy and Income Inequality" that stated that "Some taxes levied on wealth, especially on immovable property, are also an option for economies seeking more progressive taxation ... Property taxes are equitable and efficient, but underutilized in many economies ... There is considerable scope to exploit this tax more fully, both as a revenue source and as a redistributive instrument."

At the end of March 2014, the IMF secured an $18 billion bailout fund for the provisional government of Ukraine in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution.

In late 2019, the IMF estimated global growth in 2020 to reach 3.4%, but due to the coronavirus, in November 2020, it expected the global economy to shrink by 4.4%.

In March 2020, Kristalina Georgieva announced that the IMF stood ready to mobilize $1 trillion as its response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This was in addition to the $50 billion fund it had announced two weeks earlier, of which $5 billion had already been requested by Iran. One day earlier on 11 March, the UK called to pledge £150 billion to the IMF catastrophe relief fund. It came to light on 27 March that "more than 80 poor and middle-income countries" had sought a bailout due to the coronavirus.

On 13 April 2020, the IMF said that it "would provide immediate debt relief to 25 member countries under its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT)" programme.

In November 2020, the Fund warned the economic recovery may be losing momentum as COVID-19 infections rise again and that more economic help would be needed.

Member countries

Not all member countries of the IMF are sovereign states, and therefore not all "member countries" of the IMF are members of the United Nations. Amidst "member countries" of the IMF that are not member states of the UN are non-sovereign areas with special jurisdictions that are officially under the sovereignty of full UN member states, such as Aruba, Curaçao, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as Kosovo. The corporate members appoint ex-officio voting members, who are listed below. All members of the IMF are also International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) members and vice versa.

Former members are Cuba (which left in 1964), and the Republic of China (Taiwan), which was ejected from the IMF in 1980 after losing the support of then United States President Jimmy Carter and was replaced by the People's Republic of China. However, "Taiwan Province of China" is still listed in the official IMF indices.

Apart from Cuba, the other UN states that do not belong to the IMF are Liechtenstein, Monaco and North Korea. However, Andorra became the 190th member on 16 October 2020.

The former Czechoslovakia was expelled in 1954 for "failing to provide required data" and was readmitted in 1990, after the Velvet Revolution. Poland withdrew in 1950—allegedly pressured by the Soviet Union—but returned in 1986.

Qualifications

Any country may apply to be a part of the IMF. Post-IMF formation, in the early postwar period, rules for IMF membership were left relatively loose. Members needed to make periodic membership payments towards their quota, to refrain from currency restrictions unless granted IMF permission, to abide by the Code of Conduct in the IMF Articles of Agreement, and to provide national economic information. However, stricter rules were imposed on governments that applied to the IMF for funding.

The countries that joined the IMF between 1945 and 1971 agreed to keep their exchange rates secured at rates that could be adjusted only to correct a "fundamental disequilibrium" in the balance of payments, and only with the IMF's agreement.

Benefits

Member countries of the IMF have access to information on the economic policies of all member countries, the opportunity to influence other members' economic policies, technical assistance in banking, fiscal affairs, and exchange matters, financial support in times of payment difficulties, and increased opportunities for trade and investment.

Leadership

Board of Governors

The Board of Governors consists of one governor and one alternate governor for each member country. Each member country appoints its two governors. The Board normally meets once a year and is responsible for electing or appointing executive director to the Executive Board. While the Board of Governors is officially responsible for approving quota increases, special drawing right allocations, the admittance of new members, compulsory withdrawal of members, and amendments to the Articles of Agreement and By-Laws, in practice it has delegated most of its powers to the IMF's Executive Board.

The Board of Governors is advised by the International Monetary and Financial Committee and the Development Committee. The International Monetary and Financial Committee has 24 members and monitors developments in global liquidity and the transfer of resources to developing countries. The Development Committee has 25 members and advises on critical development issues and on financial resources required to promote economic development in developing countries. They also advise on trade and environmental issues.

The Board of Governors reports directly to the Managing Director of the IMF, Kristalina Georgieva.

Executive Board

24 Executive Directors make up the Executive Board. The Executive Directors represent all 189 member countries in a geographically based roster. Countries with large economies have their own Executive Director, but most countries are grouped in constituencies representing four or more countries.

Following the 2008 Amendment on Voice and Participation which came into effect in March 2011, seven countries each appoint an Executive Director: the United States, Japan, China, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia. The remaining 17 Directors represent constituencies consisting of 2 to 23 countries. This Board usually meets several times each week. The Board membership and constituency is scheduled for periodic review every eight years.

Managing Director

The IMF is led by a managing director, who is head of the staff and serves as Chairman of the Executive Board. Historically, the IMF's managing director has been a European citizen and the president of the World Bank has been an American citizen. However, this standard is increasingly being questioned and competition for these two posts may soon open up to include other qualified candidates from any part of the world. In August 2019, the International Monetary Fund has removed the age limit which is 65 or over for its managing director position.

In 2011, the world's largest developing countries, the BRIC states, issued a statement declaring that the tradition of appointing a European as managing director undermined the legitimacy of the IMF and called for the appointment to be merit-based.

List of Managing Directors

| Term | Dates | Name | Citizenship | Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 May 1946 – 5 May 1951 | Dr. Camille Gutt | Politician, Economist, Lawyer, Economics Minister, Finance Minister | |

| 2 | 3 August 1951 – 3 October 1956 | Ivar Rooth | Economist, Lawyer, Central Banker | |

| 3 | 21 November 1956 – 5 May 1963 | Per Jacobsson | Economist, Lawyer, Academic, League of Nations, BIS | |

| 4 | 1 September 1963 – 31 August 1973 | Pierre-Paul Schweitzer | Lawyer, Businessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker | |

| 5 | 1 September 1973 – 18 June 1978 | Dr. Johan Witteveen | Politician, Economist, Academic, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, CPB | |

| 6 | 18 June 1978 – 15 January 1987 | Jacques de Larosière | Businessman, Civil Servant, Central Banker | |

| 7 | 16 January 1987 – 14 February 2000 | Dr. Michel Camdessus | Economist, Civil Servant, Central Banker | |

| 8 | 1 May 2000 – 4 March 2004 | Horst Köhler | Politician, Economist, Civil Servant, EBRD, President | |

| 9 | 7 June 2004 – 31 October 2007 | Rodrigo Rato | Politician, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister, Deputy Prime Minister | |

| 10 | 1 November 2007 – 18 May 2011 | Dr. Dominique Strauss-Kahn | Politician, Economist, Lawyer, Businessman, Economics Minister, Finance Minister | |

| 11 | 5 July 2011 – 12 September 2019 | Christine Lagarde | Politician, Lawyer, Finance Minister | |

| 12 | 1 October 2019 – present | Dr. Kristalina Georgieva | Politician, Economist |

Former managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn was arrested in connection with charges of sexually assaulting a New York hotel room attendant and resigned on 18 May. The charges were later dropped. On 28 June 2011 Christine Lagarde was confirmed as managing director of the IMF for a five-year term starting on 5 July 2011. She was re-elected by consensus for a second five-year term, starting 5 July 2016, being the only candidate nominated for the post of Managing Director.

First Deputy Managing Director

The managing director is assisted by a First Deputy managing director who, by convention, has always been a citizen of the United States. Together, the Managing Director and his/her First Deputy lead the senior management of the IMF. Like the Managing Director, the First Deputy traditionally serves a five-year term.

List of First Deputy Managing Directors

| Term | Dates | Name | Citizenship | Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 February 1949 – 24 January 1952 | Andrew N. Overby | Banker, Senior U.S. Treasury Official | |

| 2 | 16 March 1953 – 31 October 1962 | H. Merle Cochran | U.S. Foreign Service Officer | |

| 3 | 1 November 1962 – 28 February 1974 | Frank A. Southard, Jr. | Economist, Civil Servant | |

| 4 | 1 March 1974 – 31 May 1984 | William B. Dale | Civil Servant | |

| 5 | 1 June 1984 – 31 August 1994 | Richard D. Erb | Economist, White House Official | |

| 6 | 1 September 1994 – 31 August 2001 | Stanley Fischer | Economist, Central Banker, Banker | |

| 7 | 1 September 2001 – 31 August 2006 | Anne O. Kreuger | Economist | |

| 8 | 17 July 2006 – 11 November 2011 | John P. Lipsky | Economist | |

| 9 | 1 September 2011 – 28 February 2020 | David Lipton | Economist, Senior U.S. Treasury Official | |

| 10 | 20 March 2020 – Present | Geoffrey W. S. Okamoto | Senior U.S. Treasury Official, Bank Consultant |

Chief Economist

The chief economist leads the research division of the IMF.

List of Chief Economists

| Term | Dates | Name | Citizenship |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1946 – 1958 | Edward M. Bernstein | |

| 2 | 1958 – 1980 | Jacques (J.J.) Polak | |

| 3 | 1980 – 1987 | William C. Hood | |

| 4 | 1987 – 1991 | Jacob Frenkel | |

| 5 | August 1991 – 29 June 2001 | Michael Mussa | |

| 6 | August 2001 – September 2003 | Kenneth Rogoff | |

| 7 | September 2003 – January 2007 | Raghuram Rajan | |

| 8 | March 2007 – 31 August 2008 | Simon Johnson | |

| 9 | 1 September 2008 – 8 September 2015 | Olivier Blanchard | |

| 10 | 8 September 2015 – 31 December 2018 | Maurice Obstfeld | |

| 11 | 1 January 2019 – | Gita Gopinath |

Voting power

Voting power in the IMF is based on a quota system. Each member has a number of basic votes (each member's number of basic votes equals 5.502% of the total votes), plus one additional vote for each special drawing right (SDR) of 100,000 of a member country's quota. The special drawing right is the unit of account of the IMF and represents a claim to currency. It is based on a basket of key international currencies. The basic votes generate a slight bias in favour of small countries, but the additional votes determined by SDR outweigh this bias. Changes in the voting shares require approval by a super-majority of 85% of voting power.

| The table below shows quota and voting shares for the largest IMF members | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In December 2015, the United States Congress adopted a legislation authorising the 2010 Quota and Governance Reforms. As a result,

- all 190 members' quotas will increase from a total of about XDR 238.5 billion to about XDR 477 billion, while the quota shares and voting power of the IMF's poorest member countries will be protected.

- more than 6 percent of quota shares will shift to dynamic emerging market and developing countries and also from over-represented to under-represented members.

- four emerging market countries (Brazil, China, India, and Russia) will be among the ten largest members of the IMF. Other top 10 members are the United States, Japan, Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy.

Effects of the quota system

The IMF's quota system was created to raise funds for loans. Each IMF member country is assigned a quota, or contribution, that reflects the country's relative size in the global economy. Each member's quota also determines its relative voting power. Thus, financial contributions from member governments are linked to voting power in the organization.

This system follows the logic of a shareholder-controlled organization: wealthy countries have more say in the making and revision of rules. Since decision making at the IMF reflects each member's relative economic position in the world, wealthier countries that provide more money to the IMF have more influence than poorer members that contribute less; nonetheless, the IMF focuses on redistribution.

Inflexibility of voting power

Quotas are normally reviewed every five years and can be increased when deemed necessary by the Board of Governors. IMF voting shares are relatively inflexible: countries that grow economically have tended to become under-represented as their voting power lags behind. Currently, reforming the representation of developing countries within the IMF has been suggested. These countries' economies represent a large portion of the global economic system but this is not reflected in the IMF's decision making process through the nature of the quota system. Joseph Stiglitz argues, "There is a need to provide more effective voice and representation for developing countries, which now represent a much larger portion of world economic activity since 1944, when the IMF was created." In 2008, a number of quota reforms were passed including shifting 6% of quota shares to dynamic emerging markets and developing countries.

Overcoming borrower/creditor divide

The IMF's membership is divided along income lines: certain countries provide financial resources while others use these resources. Both developed country "creditors" and developing country "borrowers" are members of the IMF. The developed countries provide the financial resources but rarely enter into IMF loan agreements; they are the creditors. Conversely, the developing countries use the lending services but contribute little to the pool of money available to lend because their quotas are smaller; they are the borrowers. Thus, tension is created around governance issues because these two groups, creditors and borrowers, have fundamentally different interests.

The criticism is that the system of voting power distribution through a quota system institutionalizes borrower subordination and creditor dominance. The resulting division of the IMF's membership into borrowers and non-borrowers has increased the controversy around conditionality because the borrowers are interested in increasing loan access while creditors want to maintain reassurance that the loans will be repaid.

Use

A recent source revealed that the average overall use of IMF credit per decade increased, in real terms, by 21% between the 1970s and 1980s, and increased again by just over 22% from the 1980s to the 1991–2005 period. Another study has suggested that since 1950 the continent of Africa alone has received $300 billion from the IMF, the World Bank, and affiliate institutions.

A study by Bumba Mukherjee found that developing democratic countries benefit more from IMF programs than developing autocratic countries because policy-making, and the process of deciding where loaned money is used, is more transparent within a democracy. One study done by Randall Stone found that although earlier studies found little impact of IMF programs on balance of payments, more recent studies using more sophisticated methods and larger samples "usually found IMF programs improved the balance of payments".

Exceptional Access Framework – sovereign debt

The Exceptional Access Framework was created in 2003 when John B. Taylor was Under Secretary of the US Treasury for International Affairs. The new Framework became fully operational in February 2003 and it was applied in the subsequent decisions on Argentina and Brazil. Its purpose was to place some sensible rules and limits on the way the IMF makes loans to support governments with debt problem—especially in emerging markets—and thereby move away from the bailout mentality of the 1990s. Such a reform was essential for ending the crisis atmosphere that then existed in emerging markets. The reform was closely related to and put in place nearly simultaneously with the actions of several emerging market countries to place collective action clauses in their bond contracts.

In 2010, the framework was abandoned so the IMF could make loans to Greece in an unsustainable and political situation.

The topic of sovereign debt restructuring was taken up by IMF staff in April 2013 for the first time since 2005, in a report entitled "Sovereign Debt Restructuring: Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund's Legal and Policy Framework". The paper, which was discussed by the board on 20 May, summarised the recent experiences in Greece, St Kitts and Nevis, Belize and Jamaica. An explanatory interview with Deputy Director Hugh Bredenkamp was published a few days later, as was a deconstruction by Matina Stevis of the Wall Street Journal.

The staff was directed to formulate an updated policy, which was accomplished on 22 May 2014 with a report entitled "The Fund's Lending Framework and Sovereign Debt: Preliminary Considerations", and taken up by the Executive Board on 13 June. The staff proposed that "in circumstances where a (Sovereign) member has lost market access and debt is considered sustainable ... the IMF would be able to provide Exceptional Access on the basis of a debt operation that involves an extension of maturities", which was labeled a "reprofiling operation". These reprofiling operations would "generally be less costly to the debtor and creditors—and thus to the system overall—relative to either an upfront debt reduction operation or a bail-out that is followed by debt reduction ... (and) would be envisaged only when both (a) a member has lost market access and (b) debt is assessed to be sustainable, but not with high probability ... Creditors will only agree if they understand that such an amendment is necessary to avoid a worse outcome: namely, a default and/or an operation involving debt reduction ... Collective action clauses, which now exist in most—but not all—bonds would be relied upon to address collective action problems."

Impact

According to a 2002 study by Randall W. Stone, the academic literature on the IMF shows "no consensus on the long-term effects of IMF programs on growth.

Some research has found that IMF loans can reduce the chance of a future banking crisis, while other studies have found that they can increase the risk of political crises. IMF programs can reduce the effects of a currency crisis.

Some research has found that IMF programs are less effective in countries which possess a developed-country patron (be it by foreign aid, membership of postcolonial institutions or UN voting patterns), seemingly due to this patron allowing countries to flaunt IMF program rules as these rules are not consistently enforced. Some research has found that IMF loans reduce economic growth due to creating an economic moral hazard, reducing public investment, reducing incentives to create a robust domestic policies and reducing private investor confidence. Other research has indicated that IMF loans can have a positive impact on economic growth and that their effects are highly nuanced.

Criticisms

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) research undertaken in 1980 included criticisms of the IMF which support the analysis that it is a pillar of what activist Titus Alexander calls global apartheid.

- Developed countries were seen to have a more dominant role and control over less developed countries (LDCs).

- The Fund worked on the incorrect assumption that all payments disequilibria were caused domestically. The Group of 24 (G-24), on behalf of LDC members, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) complained that the IMF did not distinguish sufficiently between disequilibria with predominantly external as opposed to internal causes. This criticism was voiced in the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis. Then LDCs found themselves with payment deficits due to adverse changes in their terms of trade, with the Fund prescribing stabilization programmes similar to those suggested for deficits caused by government over-spending. Faced with long-term, externally generated disequilibria, the G-24 argued for more time for LDCs to adjust their economies.

- Some IMF policies may be anti-developmental; the report said that deflationary effects of IMF programmes quickly led to losses of output and employment in economies where incomes were low and unemployment was high. Moreover, the burden of the deflation is disproportionately borne by the poor.

- The IMF's initial policies were based in theory and influenced by differing opinions and departmental rivalries. Critics suggest that its intentions to implement these policies in countries with widely varying economic circumstances were misinformed and lacked economic rationale.

ODI conclusions were that the IMF's very nature of promoting market-oriented approaches attracted unavoidable criticism. On the other hand, the IMF could serve as a scapegoat while allowing governments to blame international bankers. The ODI conceded that the IMF was insensitive to political aspirations of LDCs while its policy conditions were inflexible.

Argentina, which had been considered by the IMF to be a model country in its compliance to policy proposals by the Bretton Woods institutions, experienced a catastrophic economic crisis in 2001, which some believe to have been caused by IMF-induced budget restrictions—which undercut the government's ability to sustain national infrastructure even in crucial areas such as health, education, and security—and privatisation of strategically vital national resources. Others attribute the crisis to Argentina's misdesigned fiscal federalism, which caused subnational spending to increase rapidly. The crisis added to widespread hatred of this institution in Argentina and other South American countries, with many blaming the IMF for the region's economic problems. The current—as of early 2006—trend toward moderate left-wing governments in the region and a growing concern with the development of a regional economic policy largely independent of big business pressures has been ascribed to this crisis.

In 2006, a senior ActionAid policy analyst Akanksha Marphatia stated that IMF policies in Africa undermine any possibility of meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) due to imposed restrictions that prevent spending on important sectors, such as education and health.

In an interview (2008-05-19), the former Romanian Prime Minister Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu claimed that "Since 2005, IMF is constantly making mistakes when it appreciates the country's economic performances". Former Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere, who claimed that debt-ridden African states were ceding sovereignty to the IMF and the World Bank, famously asked, "Who elected the IMF to be the ministry of finance for every country in the world?"

Former chief economist of IMF and former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor Raghuram Rajan who predicted the Financial crisis of 2007–08 criticised the IMF for remaining a sideline player to the developed world. He criticised the IMF for praising the monetary policies of the US, which he believed were wreaking havoc in emerging markets. He had been critical of the ultra-loose money policies of the Western nations and IMF.

Countries such as Zambia have not received proper aid with long-lasting effects, leading to concern from economists. Since 2005, Zambia (as well as 29 other African countries) did receive debt write-offs, which helped with the country's medical and education funds. However, Zambia returned to a debt of over half its GDP in less than a decade. American economist William Easterly, sceptical of the IMF's methods, had initially warned that "debt relief would simply encourage more reckless borrowing by crooked governments unless it was accompanied by reforms to speed up economic growth and improve governance," according to The Economist.

Conditionality

The IMF has been criticised for being "out of touch" with local economic conditions, cultures, and environments in the countries they are requiring policy reform. The economic advice the IMF gives might not always take into consideration the difference between what spending means on paper and how it is felt by citizens. Countries charge that with excessive conditionality, they do not "own" the programs and the links are broken between a recipient country's people, its government, and the goals being pursued by the IMF.

Jeffrey Sachs argues that the IMF's "usual prescription is 'budgetary belt tightening to countries who are much too poor to own belts'". Sachs wrote that the IMF's role as a generalist institution specialising in macroeconomic issues needs reform. Conditionality has also been criticised because a country can pledge collateral of "acceptable assets" to obtain waivers—if one assumes that all countries are able to provide "acceptable collateral".

One view is that conditionality undermines domestic political institutions. The recipient governments are sacrificing policy autonomy in exchange for funds, which can lead to public resentment of the local leadership for accepting and enforcing the IMF conditions. Political instability can result from more leadership turnover as political leaders are replaced in electoral backlashes. IMF conditions are often criticised for reducing government services, thus increasing unemployment.

Another criticism is that IMF programs are only designed to address poor governance, excessive government spending, excessive government intervention in markets, and too much state ownership. This assumes that this narrow range of issues represents the only possible problems; everything is standardised and differing contexts are ignored. A country may also be compelled to accept conditions it would not normally accept had they not been in a financial crisis in need of assistance.

On top of that, regardless of what methodologies and data sets used, it comes to same the conclusion of exacerbating income inequality. With Gini coefficient, it became clear that countries with IMF programs face increased income inequality.

It is claimed that conditionalities retard social stability and hence inhibit the stated goals of the IMF, while Structural Adjustment Programs lead to an increase in poverty in recipient countries. The IMF sometimes advocates "austerity programmes", cutting public spending and increasing taxes even when the economy is weak, to bring budgets closer to a balance, thus reducing budget deficits. Countries are often advised to lower their corporate tax rate. In Globalization and Its Discontents, Joseph E. Stiglitz, former chief economist and senior vice-president at the World Bank, criticises these policies. He argues that by converting to a more monetarist approach, the purpose of the fund is no longer valid, as it was designed to provide funds for countries to carry out Keynesian reflations, and that the IMF "was not participating in a conspiracy, but it was reflecting the interests and ideology of the Western financial community."

Stiglitz concludes, "Modern high-tech warfare is designed to remove physical contact: dropping bombs from 50,000 feet ensures that one does not 'feel' what one does. Modern economic management is similar: from one's luxury hotel, one can callously impose policies about which one would think twice if one knew the people whose lives one was destroying."

The researchers Eric Toussaint and Damien Millet argue that the IMF's policies amount to a new form of colonization that does not need a military presence:

"Following the exigencies of the governments of the richest companies, the IMF, permitted countries in crisis to borrow in order to avoid default on their repayments. Caught in the debt's downward spiral, developing countries soon had no other recourse than to take on new debt in order to repay the old debt. Before providing them with new loans, at higher interest rates, future leaders asked the IMF, to intervene with the guarantee of ulterior reimbursement, asking for a signed agreement with the said countries. The IMF thus agreed to restart the flow of the 'finance pump' on condition that the concerned countries first use this money to reimburse banks and other private lenders, while restructuring their economy at the IMF's discretion: these were the famous conditionalities, detailed in the Structural Adjustment Programs. The IMF and its ultra-liberal experts took control of the borrowing countries' economic policies. A new form of colonization was thus instituted. It was not even necessary to establish an administrative or military presence; the debt alone maintained this new form of submission."

International politics play an important role in IMF decision making. The clout of member states is roughly proportional to its contribution to IMF finances. The United States has the greatest number of votes and therefore wields the most influence. Domestic politics often come into play, with politicians in developing countries using conditionality to gain leverage over the opposition to influence policy.

Reform

Function and policies

The IMF is only one of many international organisations, and it is a generalist institution that deals only with macroeconomic issues; its core areas of concern in developing countries are very narrow. One proposed reform is a movement towards close partnership with other specialist agencies such as UNICEF, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Jeffrey Sachs argues in The End of Poverty that the IMF and the World Bank have "the brightest economists and the lead in advising poor countries on how to break out of poverty, but the problem is development economics". Development economics needs the reform, not the IMF. He also notes that IMF loan conditions should be paired with other reforms—e.g., trade reform in developed nations, debt cancellation, and increased financial assistance for investments in basic infrastructure. IMF loan conditions cannot stand alone and produce change; they need to be partnered with other reforms or other conditions as applicable.

US influence and voting reform

The scholarly consensus is that IMF decision-making is not simply technocratic, but also guided by political and economic concerns. The United States is the IMF's most powerful member, and its influence reaches even into decision-making concerning individual loan agreements. The United States has historically been openly opposed to losing what Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew described in 2015 as its "leadership role" at the IMF, and the United States' "ability to shape international norms and practices".

Emerging markets were not well-represented for most of the IMF's history: Despite being the most populous country, China's vote share was the sixth largest; Brazil's vote share was smaller than Belgium's. Reforms to give more powers to emerging economies were agreed by the G20 in 2010. The reforms could not pass, however, until they were ratified by the US Congress, since 85% of the Fund's voting power was required for the reforms to take effect, and the Americans held more than 16% of voting power at the time. After repeated criticism, the United States finally ratified the voting reforms at the end of 2015. The OECD countries maintained their overwhelming majority of voting share, and the United States in particular retained its share at over 16%.

The criticism of the American-and-European dominated IMF has led to what some consider 'disenfranchising the world' from the governance of the IMF. Raúl Prebisch, the founding secretary-general of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), wrote that one of "the conspicuous deficiencies of the general economic theory, from the point of view of the periphery, is its false sense of universality."

Support of dictatorships

The role of the Bretton Woods institutions has been controversial since the late Cold War, because of claims that the IMF policy makers supported military dictatorships friendly to American and European corporations, but also other anti-communist and Communist regimes (such as Mobutu's Zaire and Ceaușescu's Romania, respectively). Critics also claim that the IMF is generally apathetic or hostile to human rights, and labour rights. The controversy has helped spark the anti-globalization movement.

An example of IMF's support for a dictatorship was its ongoing support for Mobutu's rule in Zaire, although its own envoy, Erwin Blumenthal, provided a sobering report about the entrenched corruption and embezzlement and the inability of the country to pay back any loans.

Arguments in favour of the IMF say that economic stability is a precursor to democracy; however, critics highlight various examples in which democratised countries fell after receiving IMF loans.

A 2017 study found no evidence of IMF lending programs undermining democracy in borrowing countries. To the contrary, it found "evidence for modest but definitively positive conditional differences in the democracy scores of participating and non-participating countries."

Impact on access to food

A number of civil society organisations have criticised the IMF's policies for their impact on access to food, particularly in developing countries. In October 2008, former United States president Bill Clinton delivered a speech to the United Nations on World Food Day, criticising the World Bank and IMF for their policies on food and agriculture:

We need the World Bank, the IMF, all the big foundations, and all the governments to admit that, for 30 years, we all blew it, including me when I was president. We were wrong to believe that food was like some other product in international trade, and we all have to go back to a more responsible and sustainable form of agriculture.

— Former U.S. president Bill Clinton, Speech at United Nations World Food Day, October 16, 2008

The FPIF remarked that there is a recurring pattern: "the destabilization of peasant producers by a one-two punch of IMF-World Bank structural adjustment programs that gutted government investment in the countryside followed by the massive influx of subsidized U.S. and European Union agricultural imports after the WTO's Agreement on Agriculture pried open markets."

Impact on public health

A 2009 study concluded that the strict conditions resulted in thousands of deaths in Eastern Europe by tuberculosis as public health care had to be weakened. In the 21 countries to which the IMF had given loans, tuberculosis deaths rose by 16.6%. A 2017 systematic review on studies conducted on the impact that Structural adjustment programs have on child and maternal health found that these programs have a detrimental effect on maternal and child health among other adverse effects.

In 2009, a book by Rick Rowden titled The Deadly Ideas of Neoliberalism: How the IMF has Undermined Public Health and the Fight Against AIDS, claimed that the IMF's monetarist approach towards prioritising price stability (low inflation) and fiscal restraint (low budget deficits) was unnecessarily restrictive and has prevented developing countries from scaling up long-term investment in public health infrastructure. The book claimed the consequences have been chronically underfunded public health systems, leading to demoralising working conditions that have fuelled a "brain drain" of medical personnel, all of which has undermined public health and the fight against HIV/AIDS in developing countries.

In 2016, the IMF's research department published a report titled "Neoliberalism: Oversold?" which, while praising some aspects of the "neoliberal agenda," claims that the organisation has been "overselling" fiscal austerity policies and financial deregulation, which they claim has exacerbated both financial crises and economic inequality around the world.

Impact on environment

IMF policies have been repeatedly criticised for making it difficult for indebted countries to say no to environmentally harmful projects that nevertheless generate revenues such as oil, coal, and forest-destroying lumber and agriculture projects. Ecuador, for example, had to defy IMF advice repeatedly to pursue the protection of its rainforests, though paradoxically this need was cited in the IMF argument to provide support to Ecuador. The IMF acknowledged this paradox in the 2010 report that proposed the IMF Green Fund, a mechanism to issue special drawing rights directly to pay for climate harm prevention and potentially other ecological protection as pursued generally by other environmental finance.

While the response to these moves was generally positive possibly because ecological protection and energy and infrastructure transformation are more politically neutral than pressures to change social policy, some experts voiced concern that the IMF was not representative, and that the IMF proposals to generate only US$200 billion a year by 2020 with the SDRs as seed funds, did not go far enough to undo the general incentive to pursue destructive projects inherent in the world commodity trading and banking systems—criticisms often levelled at the World Trade Organization and large global banking institutions.

In the context of the European debt crisis, some observers noted that Spain and California, two troubled economies within respectively the European Union and the United States, and also Germany, the primary and politically most fragile supporter of a euro currency bailout would benefit from IMF recognition of their leadership in green technology, and directly from Green Fund-generated demand for their exports, which could also improve their credit ratings.

IMF and globalization

Globalization encompasses three institutions: global financial markets and transnational companies, national governments linked to each other in economic and military alliances led by the United States, and rising "global governments" such as World Trade Organization (WTO), IMF, and World Bank. Charles Derber argues in his book People Before Profit, "These interacting institutions create a new global power system where sovereignty is globalized, taking power and constitutional authority away from nations and giving it to global markets and international bodies". Titus Alexander argues that this system institutionalises global inequality between western countries and the Majority World in a form of global apartheid, in which the IMF is a key pillar.

The establishment of globalised economic institutions has been both a symptom of and a stimulus for globalisation. The development of the World Bank, the IMF, regional development banks such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and multilateral trade institutions such as the WTO signals a move away from the dominance of the state as the primary actor analysed in international affairs. Globalization has thus been transformative in terms of a reconceptualising of state sovereignty.

Following United States President Bill Clinton's administration's aggressive financial deregulation campaign in the 1990s, globalisation leaders overturned long standing restrictions by governments that limited foreign ownership of their banks, deregulated currency exchange, and eliminated restrictions on how quickly money could be withdrawn by foreign investors.

Impact on gender equality

The IMF supports women's empowerment and tries to promotes their rights in countries with a significant gender gap.

Scandals

Managing Director Lagarde (2011-2019) was convicted of giving preferential treatment to businessman-turned-politician Bernard Tapie as he pursued a legal challenge against the French government. At the time, Lagarde was the French economic minister. Within hours of her conviction, in which she escaped any punishment, the fund's 24-member executive board put to rest any speculation that she might have to resign, praising her "outstanding leadership" and the "wide respect" she commands around the world.

Former IMF Managing Director Rodrigo Rato was arrested on 16 April 2015 for alleged fraud, embezzlement and money laundering. On 23 February 2017, the Audiencia Nacional found Rato guilty of embezzlement and sentenced to 41⁄2 years' imprisonment. In September 2018, the sentence was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Spain.

Alternatives

In March 2011, the Ministers of Economy and Finance of the African Union proposed to establish an African Monetary Fund.

At the 6th BRICS summit in July 2014 the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) announced the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) with an initial size of US$100 billion, a framework to provide liquidity through currency swaps in response to actual or potential short-term balance-of-payments pressures.

In 2014, the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank was established.

In the media

Life and Debt, a documentary film, deals with the IMF's policies' influence on Jamaica and its economy from a critical point of view. Debtocracy, a 2011 independent Greek documentary film, also criticises the IMF. Portuguese musician José Mário Branco's 1982 album FMI is inspired by the IMF's intervention in Portugal through monitored stabilisation programs in 1977–78. In the 2015 film, Our Brand Is Crisis, the IMF is mentioned as a point of political contention, where the Bolivian population fears its electoral interference.