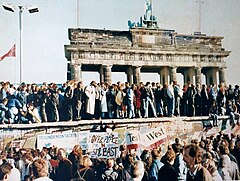

Germans stand on top of the Wall in front of Brandenburg Gate in the days before the Wall was torn down. The fall of the Berlin Wall (German: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989 was a pivotal event in world history which marked the falling of the Iron Curtain and the start of the fall of communism in Eastern and Central Europe. The fall of the inner German border took place shortly afterwards. An end to the Cold War was declared at the Malta Summit three weeks later and the German reunification took place in October the following year.

|

Background

Opening of the Iron Curtain

The opening of the Iron Curtain between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on August 19, 1989 set in motion a peaceful chain reaction, at the end of which there was no longer an East Germany and the Eastern Bloc had disintegrated. Extensive advertising for the planned picnic was made by posters and flyers among the GDR holidaymakers in Hungary. It was the largest escape movement from East Germany since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. After the picnic, which was based on an idea by Otto von Habsburg to test the reaction of the USSR and Mikhail Gorbachev to an opening of the border, tens of thousands of media-informed East Germans set off for Hungary. Erich Honecker dictated to the Daily Mirror for the Paneuropa Picnic: "Habsburg distributed leaflets far into Poland, on which the East German holidaymakers were invited to a picnic. When they came to the picnic, they were given gifts, food and Deutsche Mark, and then they were persuaded to come to the West." The leadership of the GDR in East Berlin did not dare to completely block the borders of their own country and the USSR did not respond at all. Thus the bracket of the Eastern Bloc was broken.

Following the summer of 1989, by early November refugees were finding their way to Hungary via Czechoslovakia or via the West German embassy in Prague.

The emigration was initially tolerated because of long-standing agreements with the communist Czechoslovak government, allowing free travel across their common border. However, this movement of people grew so large it caused difficulties for both countries. In addition, East Germany was struggling to meet loan payments on foreign borrowings; Egon Krenz sent Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski to unsuccessfully ask West Germany for a short-term loan to make interest payments.

Political changes in East Germany

On 18 October 1989, longtime Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) leader Erich Honecker stepped down in favor of Krenz. Honecker had been seriously ill, and those looking to replace him were initially willing to wait for a "biological solution", but by October were convinced that the political and economic situation was too grave. Honecker approved the choice, naming Krenz in his resignation speech, and the Volkskammer duly elected him. Although Krenz promised reforms in his first public speech, he was considered by the East German public to be following his predecessor's policies, and public protests demanding his resignation continued. Despite promises of reform, public opposition to the regime continued to grow.

On 1 November, Krenz authorized the reopening of the border with Czechoslovakia, which had been sealed to prevent East Germans from fleeing to West Germany. On 4 November, the Alexanderplatz demonstration took place.

On 6 November, the Interior Ministry published a draft of new travel regulations, which made cosmetic changes to Honecker-era rules, leaving the approval process opaque and maintaining uncertainty regarding access to foreign currency. The draft enraged ordinary citizens, and was denounced as "complete trash" by West Berlin Mayor Walter Momper. Hundreds of refugees crowded onto the steps of the West German embassy in Prague, enraging the Czechoslovaks, who threatened to seal off the East German-Czechoslovak border.

On 7 November, Krenz approved the resignation of Prime Minister Willi Stoph and two-thirds of the Politburo; however Krenz was unanimously re-elected as General Secretary by the Central Committee.

New East German emigration policy

On 19 October, Krenz asked Gerhard Lauter to draft a new travel policy. Lauter was a former People's Police officer. After rising rapidly through the ranks he had recently been promoted to a position with the Interior Ministry ("Home Office" / "Department of the Interior") as head of the department responsible for issuing passports and the registration of citizens.

At a Politburo meeting on 7 November it was decided to enact a portion of the draft travel regulations addressing permanent emigration immediately. Initially, the Politburo planned to create a special border crossing near Schirnding specifically for this emigration. Interior Ministry officials and Stasi bureaucrats charged with drafting the new text, however, concluded this was not feasible, and crafted a new text relating to both emigration and temporary travel. It stipulated that East German citizens could apply for permission to travel abroad without having to meet the previous requirements for those trips. To ease the difficulties, the Politburo led by Krenz decided on 9 November to allow refugees to exit directly through crossing points between East Germany and West Germany, including between East and West Berlin. Later the same day, the ministerial administration modified the proposal to include private, round-trip, travel. The new regulations were to take effect the next day.

Misinformed public announcements

The announcement of the regulations which brought down the wall took place at an hour-long press conference led by Günter Schabowski, the party leader in East Berlin and the top government spokesman, beginning at 18:00 CET on 9 November and broadcast live on East German television and radio. Schabowski was joined by Minister of Foreign Trade Gerhard Beil and Central Committee members Helga Labs and Manfred Banaschak.

Schabowski had not been involved in the discussions about the new regulations and had not been fully updated. Shortly before the press conference, he was handed a note from Krenz announcing the changes, but given no further instructions on how to handle the information. The text stipulated that East German citizens could apply for permission to travel abroad without having to meet the previous requirements for those trips, and also allowed for permanent emigration between all border crossings—including those between East and West Berlin.

At 18:53, near the end of the press conference, ANSA's Riccardo Ehrman asked if the draft travel law of 6 November was a mistake. Schabowski gave a confusing answer that asserted it was necessary because West Germany had exhausted its capacity to accept fleeing East Germans, then remembered the note he had been given and added that a new law had been drafted to allow permanent emigration at any border crossing. This caused a stir in the room; amid several questions at once, Schabowski expressed surprise that the reporters had not yet seen this law, and started reading from the note. After this, a reporter, either Ehrman or Bild-Zeitung reporter Peter Brinkmann, both of whom were sitting in the front row at the press conference, asked when the regulations would take effect. After a few seconds' hesitation, Schabowski replied, "As far as I know, it takes effect immediately, without delay" (German: Das tritt nach meiner Kenntnis … ist das sofort … unverzüglich.) This was an apparent assumption based on the note's opening paragraph; as Beil attempted to interject that it was up to the Council of Ministers to decide when it took effect, Schabowski proceeded to read this clause, which stated it was in effect until a law on the matter was passed by the Volkskammer. Crucially, a journalist then asked if the regulation also applied to the crossings to West Berlin. Schabowski shrugged and read item 3 of the note, which confirmed that it did.

After this exchange, Daniel Johnson of The Daily Telegraph asked what this law meant for the Berlin Wall. Schabowski sat frozen before giving a rambling statement about the Wall being tied to the larger disarmament question. He then ended the press conference promptly at 19:00 as journalists hurried from the room.

After the press conference, Schabowski sat for an interview with NBC news anchor Tom Brokaw in which he repeated that East Germans would be able to emigrate through the border and the regulations would go into effect immediately.

Spreading news

The news began spreading immediately: the West German Deutsche Presse-Agentur issued a bulletin at 19:04 which reported that East German citizens would be able to cross the inner German border "immediately". Excerpts from Schabowski's press conference were broadcast on West Germany's two main news programs that night—at 19:17 on ZDF's heute, which came on the air as the press conference was ending, and as the lead story at 20:00 on ARD's Tagesschau. As ARD and ZDF had broadcast to nearly all of East Germany since the late 1950s, were far more widely viewed than the East German channels, and had become accepted by the East German authorities, this is how most of the population heard the news. Later that night, on ARD's Tagesthemen, anchorman Hanns Joachim Friedrichs proclaimed, "This 9 November is a historic day. The GDR has announced that, starting immediately, its borders are open to everyone. The gates in the Wall stand open wide."

In 2009, Ehrman claimed that a member of the Central Committee had called him and urged him to ask about the travel law during the press conference, but Schabowski called that absurd. Ehrman later recanted this statement in a 2014 interview with an Austrian journalist, admitting that the caller was Günter Pötschke, head of the East German news agency ADN, and he only asked if Ehrman would attend the press conference.

Peace prayers at Nikolai Church

Despite the policy of state atheism in East Germany, Christian pastor Christian Führer regularly met with his congregation at St. Nicholas Church for prayer since 1982. Over the next seven years, the Church grew, despite authorities barricading the streets leading to it, and after church services, peaceful candlelit marches took place. The secret police issued death threats and even attacked some of the marchers, but the crowd still continued to gather. On 9 October 1989, the police and army units were given permission to use force against those assembled, but this did not deter the church service and march from taking place, which gathered 70,000 people. Many of those people started to cross into East Berlin, without a shot being fired.

Crowding of the border

After hearing the broadcast, East Germans began gathering at the Wall, at the six checkpoints between East and West Berlin, demanding that border guards immediately open the gates. The surprised and overwhelmed guards made many hectic telephone calls to their superiors about the problem. At first, they were ordered to find the "more aggressive" people gathered at the gates and stamp their passports with a special stamp that barred them from returning to East Germany—in effect, revoking their citizenship. However, this still left thousands of people demanding to be let through "as Schabowski said we can". It soon became clear that no one among the East German authorities would take personal responsibility for issuing orders to use lethal force, so the vastly outnumbered soldiers had no way to hold back the huge crowd of East German citizens. Mary Elise Sarotte in a 2009 Washington Post story characterized the series of events leading to the fall of the wall as an accident, saying "One of the most momentous events of the past century was, in fact, an accident, a semicomical and bureaucratic mistake that owes as much to the Western media as to the tides of history."

Border openings

Finally, at 10:45 p.m. (alternatively given as 11:30 p.m.) on 9 November, Harald Jäger, commander of the Bornholmer Straße border crossing, yielded, allowing guards to open the checkpoints and letting people through with little or no identity-checking. As the Ossis swarmed through, they were greeted by Wessis waiting with flowers and champagne amid wild rejoicing. Soon afterward, a crowd of West Berliners jumped on top of the Wall and were soon joined by East German youngsters. The evening of 9 November 1989 is known as the night the Wall came down.

Walking through Checkpoint Charlie, 10 November 1989

At the Brandenburg Gate, 10 November 1989

Celebration at the border crossing in the Schlutup district of Lübeck

Another border crossing to the south may have been opened earlier. An account by Heinz Schäfer indicates that he also acted independently and ordered the opening of the gate at Waltersdorf-Rudow a couple of hours earlier. This may explain reports of East Berliners appearing in West Berlin earlier than the opening of the Bornholmer Straße border crossing.

"Wallpeckers" demolition

Removal of the Wall began on the evening of 9 November 1989 and continued over the following days and weeks, with people nicknamed Mauerspechte (wallpeckers) using various tools to chip off souvenirs, demolishing lengthy parts in the process, and creating several unofficial border crossings.

Television coverage of citizens demolishing sections of the Wall on 9 November was soon followed by the East German regime announcing ten new border crossings, including the historically significant locations of Potsdamer Platz, Glienicker Brücke, and Bernauer Straße. Crowds gathered on both sides of the historic crossings waiting for hours to cheer the bulldozers that tore down portions of the Wall to reconnect the divided roads. While the Wall officially remained guarded at a decreasing intensity, new border crossings continued for some time. Initially the East German Border Troops attempted repairing damage done by the "wallpeckers"; gradually these attempts ceased, and guards became more lax, tolerating the increasing demolitions and "unauthorized" border crossing through the holes.

Prime ministers meet

The Brandenburg Gate in the Berlin Wall was opened on 22 December 1989; on that date, West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl walked through the gate and was greeted by East German Prime Minister Hans Modrow. West Germans and West Berliners were allowed visa-free travel starting 23 December. Until then, they could only visit East Germany and East Berlin under restrictive conditions that involved application for a visa several days or weeks in advance and obligatory exchange of at least 25 DM per day of their planned stay, all of which hindered spontaneous visits. Thus, in the weeks between 9 November and 23 December, East Germans could actually travel more freely than Westerners.

Official demolition

On 13 June 1990, the East German Border Troops officially began dismantling the Wall, beginning in Bernauer Straße and around the Mitte district. From there, demolition continued through Prenzlauer Berg/Gesundbrunnen, Heiligensee and throughout the city of Berlin until December 1990. According to estimates by the border troops, a total of around 1.7 million tonnes of building rubble was produced by the demolition. Unofficially, the demolition of the Bornholmer Straße began because of construction work on the railway. This involved a total of 300 GDR border guards and—after 3 October 1990—600 Pioneers of the Bundeswehr. These were equipped with 175 trucks, 65 cranes, 55 excavators and 13 bulldozers. Virtually every road that was severed by the Berlin Wall, every road that once linked from West Berlin to East Berlin, was reconstructed and reopened by 1 August 1990. In Berlin alone, 184 km (114 mi) of wall, 154 km (96 mi) border fence, 144 km (89 mi) signal systems and 87 km (54 mi) barrier ditches were removed. What remained were six sections that were to be preserved as a memorial. Various military units dismantled the Berlin/Brandenburg border wall, completing the job in November 1991. Painted wall segments with artistically valuable motifs were put up for auction in 1990 in Berlin and Monte Carlo.

On 1 July 1990, the day East Germany adopted the West German currency, all de jure border controls ceased, although the inter-German border had become meaningless for some time before that. The demolition of the Wall was completed in 1994.

The fall of the Wall marked the first critical step towards German reunification, which formally concluded a mere 339 days later on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of East Germany and the official reunification of the German state along the democratic lines of the West German Basic Law.

A crane removes a section of the Wall near Brandenburg Gate on 21 December 1989.

Short section of the Berlin Wall at Potsdamer Platz, March 2009

International opposition

French President François Mitterrand and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher both opposed the fall of the Berlin Wall and the eventual reunification of Germany, fearing potential German designs on its neighbours using its increased strength. In September 1989, Margaret Thatcher privately confided to Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev that she wanted the Soviet leader to do what he could to stop it.

We do not want a united Germany. This would lead to a change to postwar borders and we cannot allow that because such a development would undermine the stability of the whole international situation and could endanger our security, Thatcher told Gorbachev.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, François Mitterrand warned Thatcher that a unified Germany could make more ground than Adolf Hitler ever had and that Europe would have to bear the consequences.

Legacy

Celebrations and anniversaries

On 21 November 1989, Crosby, Stills & Nash performed the song "Chippin' Away" from Graham Nash's 1986 solo album Innocent Eyes in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

On 25 December 1989, Leonard Bernstein gave a concert in Berlin celebrating the end of the Wall, including Beethoven's 9th symphony (Ode to Joy) with the word "Joy" (Freude) changed to "Freedom" (Freiheit) in the lyrics sung. The poet Schiller may have originally written "Freedom" and changed it to "Joy" out of fear. The orchestra and choir were drawn from both East and West Germany, as well as the United Kingdom, France, the Soviet Union, and the United States. On New Year's Eve 1989, David Hasselhoff performed his song "Looking for Freedom" while standing atop the partly demolished wall. Roger Waters performed the Pink Floyd album The Wall just north of Potsdamer Platz on 21 July 1990, with guests including Bon Jovi, Scorpions, Bryan Adams, Sinéad O'Connor, Cyndi Lauper, Thomas Dolby, Joni Mitchell, Marianne Faithfull, Levon Helm, Rick Danko and Van Morrison.

Over the years, there has been a repeated controversial debate as to whether 9 November would make a suitable German national holiday, often initiated by former members of political opposition in East Germany, such as Werner Schulz. Besides being the emotional apogee of East Germany's peaceful revolution, 9 November is also the date of the 1918 abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and declaration of the Weimar Republic, the first German republic. However, 9 November is also the anniversary of the execution of Robert Blum following the 1848 Vienna revolts, the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch and the infamous Kristallnacht pogroms of the Nazis in 1938. Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel criticised the first euphoria, noting that "they forgot that 9 November has already entered into history—51 years earlier it marked the Kristallnacht." As reunification was not official and complete until 3 October (1990), that day was finally chosen as German Unity Day.

10th anniversary celebrations

On 9 November 1999, the 10th anniversary was observed with a concert and fireworks at the vid Brandenburg Gate. Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich played music by Johann Sebastian Bach, while German rock band Scorpions performed their 1990 song Wind of Change. Wreaths were placed for victims shot down when they attempted to escape to the west, and politicians delivered speeches.

20th anniversary celebrations

On 9 November 2009, Berlin celebrated the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall with a "Festival of Freedom" with dignitaries from around the world in attendance for an evening celebration around the Brandenburg Gate. A high point was when over 1,000 colourfully designed foam domino tiles, each over 8 feet (2.4 m) tall, that were stacked along the former route of the Wall in the city center were toppled in stages, converging in front of the Brandenburg Gate.

A Berlin Twitter Wall was set up to allow Twitter users to post messages commemorating the 20th anniversary. The Chinese government quickly shut down access to the Twitter Wall after masses of Chinese users began using it to protest the Great Firewall of China.

In the United States, the German Embassy coordinated a public diplomacy campaign with the motto "Freedom Without Walls", to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. The campaign was focused on promoting awareness of the fall of the Berlin Wall among current college students. Students at over 30 universities participated in "Freedom Without Walls" events in late 2009. First place winner of the Freedom Without Walls Speaking Contest Robert Cannon received a free trip to Berlin for 2010.

An international project called Mauerreise (Journey of the Wall) took place in various countries. Twenty symbolic Wall bricks were sent from Berlin starting in May 2009, with the destinations being Korea, Cyprus, Yemen, and other places where everyday life is characterised by division and border experience. In these places, the bricks would become a blank canvas for artists, intellectuals and young people to tackle the "wall" phenomenon.

To commemorate the 20th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the 3D online virtual world Twinity reconstructed a true-to-scale section of the Wall in virtual Berlin. The MTV Europe Music Awards, on 5 November, had U2 and Tokio Hotel perform songs dedicated to, and about the Berlin Wall. U2 performed at the Brandenburg Gate, and Tokio Hotel performed "World Behind My Wall".

Palestinians in the town of Kalandia, West Bank pulled down parts of the Israeli West Bank barrier, in a demonstration marking the 20th Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

The International Spy Museum in Washington D.C., hosted a Trabant car rally where 20 Trabants gathered in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Rides were raffled every half-hour and a Trabant crashed through a Berlin Wall mock up. The Trabant was the East German people's car that many used to leave DDR after the collapse.

The Allied Museum in the Dahlem district of Berlin hosted a number of events to mark the Twentieth Anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall. The museum held a Special Exhibition entitled "Wall Patrol – The Western Powers and the Berlin Wall 1961–1990" which focused on the daily patrols deployed by the Western powers to observe the situation along the Berlin Wall and the fortifications on the GDR border. A sheet of "Americans in Berlin" Commemorative Cinderella stamps designed by T.H.E. Hill, the author of the novel Voices Under Berlin, was presented to the Museum by David Guerra, Berlin veteran and webmaster of the site www.berlinbrigade.com. The stamps splendidly illustrate that even twenty years on, veterans of service in Berlin still regard their service there as one of the high points of their lives.

30th anniversary celebrations

Berlin planned a weeklong arts festival from 4 to 10 November 2019 and a citywide music festival on 9 November to celebrate the 30th anniversary. On 4 November, outdoor exhibits opened at Alexanderplatz, the Brandenburg Gate, the East Side Gallery, Gethsemane Church, Kurfürstendamm, Schlossplatz, and the former Stasi headquarters in Lichtenberg.

Hertha Berlin commemorated the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall by tearing a fake Berlin Wall in their match against RB Leipzig.