Sustainability is the capacity to endure in a relatively ongoing way across various domains of life. In the 21st century, it refers generally to the capacity for Earth's biosphere and human civilization to co-exist. Sustainability has also been described as "meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs" (Brundtland, 1987). For many, sustainability is defined through the interconnected domains of environment, economy and society. Despite the increased popularity of the term "sustainability" and its usage, the possibility that human societies will achieve environmental sustainability has been, and continues to be, questioned—in light of environmental degradation, biodiversity loss, climate change, overconsumption, population growth and societies' pursuit of unlimited economic growth in a closed system.

A related concept is that of "sustainable development", which is often discussed through the domains of culture, technology economics and politics. According to Our Common Future (Brundtland Report in 1987), sustainable development is defined as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

Moving towards sustainability can involve social challenges that entail the following: international and national law, urban planning and transport, supply-chain management, local and individual lifestyles and ethical consumerism.

Definitions

Originally, "sustainability" meant making only such use of natural, renewable resources that people could continue to rely on their yields in the long term. The concept of sustainability, or Nachhaltigkeit in German, can be traced back to Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), and was applied to forestry. However, the idea itself goes back to times immemorial, as communities have always worried about the capacity of their environment to sustain them in the long term. Many ancient cultures had traditions restricting the use of natural resources, e.g. the Maoris of New Zealand, the Amerindians of coastal British Columbia and peoples of Indonesia, Oceania, India and Mali.

Modern use of the term "sustainability" really begins with the UN Commission on Environment and Development, also known as the Brundtland Commission, set up in 1983. According to Our Common Future (also known as the "Brundtland Report"), sustainable development is defined as development that "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." Sustainable development may be the organizing principle of sustainability, yet others may view the two terms as paradoxical (seeing development as inherently unsustainable).

The word sustainability is also used widely by development agencies and international charities to focus their poverty alleviation efforts in ways that can be sustained by the local populace and its environment.

Three dimensions of sustainability

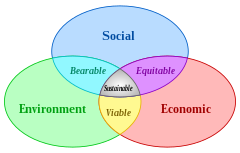

A different view of sustainability emerged in the 1990s. Here, sustainability is not seen in terms of confronting human aspirations for increased well-being with the limitations imposed by the environment, but rather as a systems view of these aspirations, incorporating environmental concerns. Under this conception, sustainability is defined through the following interconnected domains or pillars: environmental, economic and social. In crude versions of this view (also termed the ‘triple bottom line’), the three dimensions are equivalent, and the aim is to achieve a balance between them. More sophisticated versions recognize that the economic dimension is subsumed under the social one (i.e., the economy is part of society), and that the environmental dimension constrains both the social and the economic one. In fact, the three pillars are interdependent, and in the long run, none can exist without the others. The term "sustainability" and its derived definition continue to change and adapt as the world advances and opinions develop.

The 2005 World Summit on Social Development identified sustainable development goals (SDGs), such as economic development, social development, and environmental protection. This view can be expressed as a “wedding-cake” model, in which each of the 17 SDGs is assigned to one of the three dimensions.

The three pillars have served as a common ground for numerous sustainability standards and certification systems, in particular in the food industry. Standards which today explicitly refer to the triple bottom line include Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, UTZ Certified, and GLOBALG.A.P. Sustainability standards are used in global supply chains in various sectors and industries such as agriculture, mining, forestry, and fisheries. Based on the ITC Standards, the most frequently covered products are agricultural products, followed by processed food.

|

A study from 2005 pointed out that environmental justice is as important as sustainable development. Ecological economist Herman Daly asked, "what use is a sawmill without a forest?" From this perspective, the economy is a subsystem of human society, which is itself a subsystem of the biosphere, and a gain in one sector is a loss in another. This perspective led to the nested circles' figure (above) of 'economics' inside 'society' inside the 'environment'.

Thus, the simple definition of sustainability as something that may constrain development has been expanded to incorporate improving the quality of human life. This conveys the idea of sustainability having quantifiable limits. On the other hand, sustainability is also a call to action, a task in progress or "journey" and therefore a political process, so some definitions set out common goals and values. The Earth Charter speaks of "a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace." This suggests a more complex image of sustainability, which includes the domain of politics. Essentially, sustainability can not be ensured through one route means of focus, attention, and action. It must be cultivated through a complete targeting of the object itself to ensure results and feasibility.

More than that, sustainability implies responsible and proactive decision-making and innovation that minimizes negative impact and maintains a balance between ecological resilience, economic prosperity, political justice and cultural vibrancy to ensure a desirable planet for all species now and in the future. Specific fields of sustainability include, sustainable agriculture, sustainable architecture or ecological economics. Understanding sustainable development is important but without clear targets, it remains an unfocused term like "liberty" or "justice." It has also been described as a "dialogue of values that challenge the sociology of development."

Further dimensions of sustainability

Some sustainability experts and practitioners have proposed additional pillars of sustainability. A common one is culture, resulting in a quadruple bottom line. There is also an opinion that considers resource use and financial sustainability as two additional pillars of sustainability. In infrastructure projects, for instance, one must ask whether sufficient financing capability for maintenance exists.

An example of this four-dimensional view is the Circles of Sustainability approach, which includes cultural sustainability. This goes beyond the three dimensions of the United Nations Millennium Declaration but is in accord with the United Nations, Unesco, Agenda 21, and in particular the Agenda 21 for culture which specifies culture as the fourth domain of sustainable development. The model is now being used by organizations such as the United Nations Cities Program and Metropolis. In the case of Metropolis, this approach does not mean adding a fourth domain of culture to the dominant triple bottom line figure of the economy, environment and the social. Rather, it involves treating all four domains—economy, ecology, politics, and culture—as social (including economics) and distinguishing between ecology (as the intersection of the human and natural worlds) and the environment as that which goes far beyond what we as humans can ever know.

Another model suggests humans' attempt to achieve all of their needs and aspirations via seven modalities: economy, community, occupational groups, government, environment, culture, and physiology. From the global to the individual human scale, each of the seven modalities can be viewed across seven hierarchical levels. Human sustainability can be achieved by attaining sustainability in all levels of the seven modalities.

Others

Sustainability can also be defined as a socio-ecological process characterized by the pursuit of a common ideal. An ideal is by definition unattainable in a given time and space. However, by persistently and dynamically approaching it, the process results in a sustainable system. Many environmentalists and ecologists argue that sustainability is achieved through the balance of species and the resources within their environment. As is typically practiced in natural resource management, the goal is to maintain this equilibrium, so available resources must not be depleted faster than resources are naturally generated.

Sustainable development

Principles and concepts

The philosophical and analytic framework of sustainability draws on and connects with many different disciplines and fields; this is also called sustainability science.

Scale and context

Sustainability is studied and managed over many scales (levels or frames of reference) of time and space and in many contexts of environmental, social, and economic organizations. The focus ranges from the total carrying capacity (sustainability) of planet Earth to the sustainability of economic sectors, ecosystems, countries, municipalities, neighborhoods, home gardens, individual lives, individual goods and services, occupations, lifestyles, and behavior patterns. Since the overarching theme of sustainability includes the prudent use of resources to meet current needs without affecting the ability of the future generation from meeting their needs, sustainability can entail the full compass of biological and human activity or any part of it. As Daniel Botkin, author and environmentalist, has stated: "We see a landscape that is always in flux, changing over many scales of time and space."

The sheer size and complexity of the planetary ecosystem have proven problematic for the design of practical measures to reach global sustainability. To shed light on the big picture, explorer and sustainability campaigner Jason Lewis has drawn parallels to other, more tangible closed systems. For example, Lewis likens human existence on Earth — isolated as the planet is in space, whereby people cannot be evacuated to relieve population pressure and resources cannot be imported to prevent accelerated depletion of resources — to life at sea on a small boat isolated by water. In both cases, Lewis argues, exercising the precautionary principle is a key factor in survival.

Consumption

A major aspect of human impact on Earth systems is the destruction of biophysical resources, and in particular, the Earth's ecosystems. The environmental impact of a community or humankind as a whole depends both on population and impact per person, which in turn depends in complex ways on what resources are being used, whether or not those resources are renewable, and the scale of the human activity relative to the carrying capacity of the ecosystems involved. Careful resource management can be applied at many scales, from economic sectors like agriculture, manufacturing and industry, to work organizations, the consumption patterns of households and individuals, and the resource demands of individual goods and services.

One of the initial attempts to express human impact mathematically was developed in the 1970s and is called the I PAT formula. This formulation attempts to explain human consumption in terms of three components: population numbers, levels of consumption (which it terms "affluence", although the usage is different), and impact per unit of resource use (which is termed "technology", because this impact depends on the technology used). The equation is expressed:

- I = P × A × T

- Where: I = Environmental impact, P = Population, A = Affluence, T = Technology

According to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, human consumption, with current policy, by the year 2100 will be 7 times bigger than in the year 2010.

Resilience

Resilience in ecology is the capacity of an ecosystem to absorb disturbance and still retain its basic structure and viability. Resilience-thinking evolved from the need to manage interactions between human-constructed systems and natural ecosystems sustainably, even though to policymakers, a definition remains elusive. Resilience-thinking addresses how much planetary ecological systems can withstand assaults from human disturbances and still deliver the service's current and future generations need from them. It is also concerned with commitment from geopolitical policymakers to promote and manage essential planetary ecological resources to promote resilience and achieve sustainability of these essential resources for the benefit of future generations of life. The resilience of an ecosystem, and thereby, its sustainability, can be reasonably measured at junctures or events where the combination of naturally occurring regenerative forces (solar energy, water, soil, atmosphere, vegetation, and biomass) interact with the energy released into the ecosystem from disturbances.

Resilience has its limits, however: an ecosystem may reach a tipping-point, beyond which it will lose its capacity for restoration and change irreparably.

The most practical view of sustainability is in terms of efficiency. In fact, efficiency equals sustainability since optimum efficiency (when possible) means zero waste. Another not so practical view of sustainability is closed systems that maintain processes of productivity indefinitely by replacing resources used by actions of people with resources of equal or greater value by those same people without degrading or endangering natural biotic systems. In this way, sustainability can be concretely measured in human projects if there is a transparent accounting of the resources put back into the ecosystem to replace those displaced. In nature, the accounting occurs naturally through a process of adaptation as an ecosystem returns to viability from an external disturbance. The adaptation is a multi-stage process that begins with the disturbance event (earthquake, volcanic eruption, hurricane, tornado, flood, or thunderstorm), followed by absorption, utilization, or deflection of the energy or energies that the external forces created.

In analyzing systems such as urban and national parks, dams, farms and gardens, theme parks, open-pit mines, water catchments, one way to look at the relationship between sustainability and resilience is to view the former with a long-term vision, and resilience as the capacity of human engineers to respond to immediate environmental events.

An alternative way of thinking is to distinguish between what has been called ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ sustainability. The former refers to environmental resources that can be replaced or substituted for, such as fossil fuels, many minerals, forests and polluted air. The latter refers to resources that once lost cannot be recovered or repaired within a reasonable timescale, such as biodiversity, soils or climate. Different policies and strategies are needed for the two types.

Carrying capacity

At the global scale, scientific data now indicates that humans are living beyond the carrying capacity of planet Earth and that this cannot continue indefinitely. This scientific evidence comes from many sources but is presented in detail in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the planetary boundaries framework. An early detailed examination of global limits was published in the 1972 book Limits to Growth, which has prompted follow-up commentary and analysis. A 2012 review in Nature by 22 international researchers expressed concerns that the Earth may be "approaching a state shift" in its biosphere.

The ecological footprint measures human consumption in terms of the biologically productive land and sea area needed to provide for all the competing demands on nature, including the provision of food, fiber, the accommodation of urban infrastructure and the absorption of waste, including carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuel. In 2019, it required on average 2.8 global hectares per person worldwide, 75% more than the biological capacity of 1.6 global hectares available on this planet per person (this space includes the space needed for wild species). The resulting ecological deficit must be met from unsustainable extra sources and these are obtained in three ways: embedded in the goods and services of world trade; taken from the past (e.g. fossil fuels); or borrowed from the future as unsustainable resource usage (e.g. by over exploiting forests and fisheries).

The figure (right) examines sustainability at the scale of individual countries by contrasting their Ecological Footprint with their UN Human Development Index (a measure of standard of living). The graph shows what is necessary for countries to maintain an acceptable standard of living for their citizens while, at the same time, maintaining sustainable resource use. The general trend is for higher standards of living to become less sustainable. As always, population growth has a marked influence on levels of consumption and the efficiency of resource use. The sustainability goal is to raise the global standard of living without increasing the use of resources beyond globally sustainable levels; that is, to not exceed "one planet" consumption. The information generated by reports at the national, regional and city scales confirm the global trend towards societies that are becoming less sustainable over time.

At the enterprise scale, carrying capacity now also plays a critical role in making it possible to measure and report the sustainability performance of individual organizations. This is most clearly demonstrated through use of Context-Based Sustainability (CBS) tools, methods and metrics, including the MultiCapital Scorecard, which has been in development since 2005. Contrary to many other mainstream approaches to measuring the sustainability performance of organizations – which tend to be more incrementalist in form – CBS is explicitly tied to social, environmental and economic limits and thresholds in the world. Thus, rather than simply measure and report changes in relative terms from one period to another, CBS makes it possible to compare the impacts of organizations to organization-specific norms, standards or thresholds for what they (the impacts) would have to be in order to be empirically sustainable (i.e., which if generalized to a larger population would not fail to maintain the sufficiency of vital resources for human or non-human well-being).

Measurement

Sustainability measurement is the quantitative basis for the informed management of sustainability. The metrics used for the measurement of sustainability (involving the sustainability of environmental, social and economic domains, both individually and in various combinations) are still evolving: they include indicators, benchmarks, audits, sustainability standards and certification systems like Fairtrade and Organic, indexes and accounting, as well as assessment, appraisal and other reporting systems. They are applied over a wide range of spatial and temporal scales.

Some of the widely used sustainability measures include corporate sustainability reporting, Triple Bottom Line accounting, World Sustainability Society, and estimates of the quality of sustainability governance for individual countries using the Environmental Sustainability Index and Environmental Performance Index. An alternative approach, used by the United Nations Global Compact Cities Programme and explicitly critical of the triple-bottom-line approach is Circles of Sustainability.

Two related concepts to understand if the mode of life of humanity is sustainable, are planetary boundaries and ecological footprint. If the boundaries are not crossed and the ecological footprint is not exceeding the carrying capacity of the biosphere, the mode of life is regarded as sustainable.Environmental dimension

Environmental management

At the global scale and in the broadest sense environmental management involves the oceans, freshwater systems, land and atmosphere. Following the sustainability principle of scale, it can be equally applied to any ecosystem from a tropical rainforest to a home garden.

Healthy ecosystems provide vital goods and services to humans and other organisms. There are two major ways of reducing negative human impact and enhancing ecosystem services and the first of these is environmental management. This direct approach is based largely on information gained from earth science, environmental science and conservation biology. However, this is management at the end of a long series of indirect causal factors that are initiated by human consumption, so a second approach is through demand management of human resource use.

Management of human consumption of resources is an indirect approach based largely on information gained from economics. Three broad criteria for ecological sustainability were describe in 1990: renewable resources should provide a sustainable yield (the rate of harvest should not exceed the rate of regeneration); for non-renewable resources there should be equivalent development of renewable substitutes; waste generation should not exceed the assimilative capacity of the environment.

According to the Brundtland report, "poverty is a major cause and effect of global environmental problems. It is therefore futile to attempt to deal with environmental problems without a broader perspective that encompasses the factors underlying world poverty and international inequality."

Atmosphere

At a March 2009 meeting of the Copenhagen Climate Council, 2,500 climate experts from 80 countries issued a keynote statement that there is now "no excuse" for failing to act on global warming and that without strong carbon reduction "abrupt or irreversible" shifts in climate may occur that "will be very difficult for contemporary societies to cope with." Management of the global atmosphere now involves assessment of all aspects of the carbon cycle to identify opportunities to address human-induced climate change and this has become a major focus of scientific research because of the potential catastrophic effects on biodiversity and human communities.

Other human impacts on the atmosphere include the air pollution in cities, the pollutants including toxic chemicals like nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, volatile organic compounds and airborne particulate matter that produce photochemical smog and acid rain, and the chlorofluorocarbons that degrade the ozone layer. Anthropogenic particulates such as sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere reduce the direct irradiance and reflectance (albedo) of the Earth's surface. Known as global dimming, the decrease is estimated to have been about 4% between 1960 and 1990 although the trend has subsequently reversed. Global dimming may have disturbed the global water cycle by reducing evaporation and rainfall in some areas. It also creates a cooling effect and this may have partially masked the effect of greenhouse gases on global warming.

Reforestation is one of the ways to stop desertification fueled by anthropogenic climate change and non-sustainable land use. One of the most important projects is the Great Green Wall that should stop the expansion of Sahara desert to the south. By 2018 only 15% of it is accomplished, but there are already many positive effects, which include: "Over 12 million acres (5 million hectares) of degraded land has been restored in Nigeria; roughly 30 million acres of drought-resistant trees have been planted across Senegal; and a whopping 37 million acres of land has been restored in Ethiopia – just to name a few of the states involved"; "many groundwater wells refilled with drinking water, rural towns with additional food supplies, and new sources of work and income for villagers, thanks to the need for tree maintenance."

Land use

Loss of biodiversity stems largely from the habitat loss and fragmentation produced by the human appropriation of land for development, forestry and agriculture as natural capital is progressively converted to man-made capital. Land use change is fundamental to the operations of the biosphere because alterations in the relative proportions of land dedicated to urbanisation, agriculture, forest, woodland, grassland and pasture have a marked effect on the global water, carbon and nitrogen biogeochemical cycles and this can impact negatively on both natural and human systems. At the local human scale, major sustainability benefits accrue from sustainable parks and gardens and green cities.

Since the Neolithic Revolution about 47% of the world's forests have been lost to human use. Present-day forests occupy about a quarter of the world's ice-free land with about half of these occurring in the tropics. In temperate and boreal regions forest area is gradually increasing (except for Siberia), but deforestation in the tropics is of major concern.

Food is essential to life. Feeding almost eight billion human bodies takes a heavy toll on the Earth's resources. This begins with the appropriation of about 38% of the Earth's land surface and about 20% of its net primary productivity. Added to this are the resource-hungry activities of industrial agribusiness—everything from the crop need for irrigation water, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides to the resource costs of food packaging, transport (now a major part of global trade) and retail. Environmental problems associated with industrial agriculture and agribusiness are now being addressed through such movements as sustainable agriculture, organic farming and more sustainable business practices. The most cost-effective mitigation options in the Agriculture, Forestry, and Other Land Use sector include afforestation, sustainable forest management, and reducing deforestation.

Population

Sustainable population refers to a proposed sustainable human population of Earth or a particular region of Earth, such as a nation or continent. Estimates vary widely, with estimates based on different figures ranging from 0.65 billion people to 98 billion, with 8 billion people being a typical estimate. Projections of population growth, evaluations of overconsumption and associated human pressures on the environment have led to some to advocate for what they consider a sustainable population. Proposed policy solutions vary, including sustainable development, female education, family planning and broad human population planning.

Emerging economies like those of China and India aspire to the living standards of the Western world, as does the non-industrialized world in general. It is the combination of population increase in the developing world and unsustainable consumption levels in the developed world that poses a stark challenge to sustainability.

According to the UN Population Fund, high fertility and poverty have been strongly correlated, and the world's poorest countries also have the highest fertility and population growth rates.Management of human consumption

The underlying driver of direct human impacts on the environment is human consumption. This impact is reduced by not only consuming less but also making the full cycle of production, use, and disposal more sustainable. Consumption of goods and services can be analyzed and managed at all scales through the chain of consumption, starting with the effects of individual lifestyle choices and spending patterns, through to the resource demands of specific goods and services, the impacts of economic sectors, through national economies to the global economy. Analysis of consumption patterns relates resource use to the environmental, social and economic impacts at the scale or context under investigation. The ideas of embodied resource use (the total resources needed to produce a product or service), resource intensity, and resource productivity are important tools for understanding the impacts of consumption. Key resource categories relating to human needs are food, energy, raw materials and water.

In 2010, the International Resource Panel, hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), published the first global scientific assessment on the impacts of consumption and production and identified priority actions for developed and developing countries. The study found that the most critical impacts are related to ecosystem health, human health and resource depletion. From a production perspective, it found that fossil-fuel combustion processes, agriculture and fisheries have the most important impacts. Meanwhile, from a final consumption perspective, it found that household consumption related to mobility, shelter, food, and energy-using products causes the majority of life-cycle impacts of consumption.

In 2021, a study checked if the current situation confirms the predictions of the book Limits to growth. The conclusion was that in 10 years the global GDP will begin to decline. If it will not happen by deliberate transition it will happen by ecological disaster.

Energy

The Sun's energy, stored by plants, algae and certain bacteria (primary producers) during photosynthesis, passes through the food chain to other organisms to ultimately power all living processes. Since the industrial revolution the concentrated energy of the Sun stored in fossilized plants as fossil fuels has been a major driver of technology which, in turn, has been the source of both economic and political power. In 2021 climate scientists of the IPCC concluded “it is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land”. The largest driver is fossil fuel emissions, but changes in land use are important too. The 2014 IPCC Summary for Policymakers noted that direct CO2 emissions from the energy supply sector are projected to almost double by 2050. Stabilizing the world's climate will require high-income countries to reduce their emissions by 60–90% over 2006 levels by 2050 which should hold CO2 levels at 450–650 ppm from current levels of about 410 ppm. Above this level, temperatures could rise by more than 2 °C to produce "catastrophic" climate change. Reduction of current CO2 levels must be achieved against a background of global population increase and developing countries aspiring to energy-intensive high consumption.

Reducing greenhouse emissions is being tackled at all scales, ranging from tracking the passage of carbon through the carbon cycle to the commercialization of renewable energy, developing less carbon-hungry technology and transport systems and attempts by individuals to lead carbon-neutral lifestyles by monitoring the fossil fuel use embodied in all the goods and services they use. Carbon capture and storage technology could reduce the life cycle of greenhouse gas emissions of fossil fuel power plants. Engineering of emerging technologies such as carbon-neutral fuel and energy storage systems such as power to gas, compressed air energy storage, and pumped-storage hydroelectricity are necessary to store power from transient renewable energy sources including emerging renewables such as airborne wind turbines.

Renewable energy also has some environmental impacts. They are presented by the proponents of theories such as degrowth, steady-state economy and circular economy as one of the proofs that for achieving sustainability technological methods are not enough and there is a need to limit consumption

Water

Water security and food security are inextricably linked. In the decade 1951–60 human water withdrawals were four times greater than the previous decade. This rapid increase resulted from scientific and technological developments impacting through the economy—especially the increase in irrigated land, growth in industrial and power sectors, and intensive dam construction on all continents. This altered the water cycle of rivers and lakes, affected their water quality and had a significant impact on the global water cycle. Currently towards 35% of human water use is unsustainable, drawing on diminishing aquifers and reducing the flows of major rivers: this percentage is likely to increase if climate change impacts become more severe, populations increase, aquifers become progressively depleted and supplies become polluted and unsanitary. From 1961 to 2001 water demand doubled—agricultural use increased by 75%, industrial use by more than 200%, and domestic use more than 400%. In the 1990s it was estimated that humans were using 40–50% of the globally available freshwater in the approximate proportion of 70% for agriculture, 22% for industry, and 8% for domestic purposes with total use progressively increasing.

Water efficiency is being improved on a global scale by increased demand management, improved infrastructure, improved water productivity of agriculture, minimising the water intensity (embodied water) of goods and services, addressing shortages in the non-industrialized world, concentrating food production in areas of high productivity, and planning for climate change, such as through flexible system design. A promising direction towards sustainable development is to design systems that are flexible and reversible. At the local level, people are becoming more self-sufficient by harvesting rainwater and reducing use of mains water.

Food

The American Public Health Association (APHA) defines a "sustainable food system" as "one that provides healthy food to meet current food needs while maintaining healthy ecosystems that can also provide food for generations to come with minimal negative impact to the environment. A sustainable food system also encourages local production and distribution infrastructures and makes nutritious food available, accessible, and affordable to all. Further, it is humane and just, protecting farmers and other workers, consumers, and communities."

Apart from the environmental impact described above (section on Land Use), the current food system causes health problems associated with obesity in the rich world and hunger in the poor world. This has generated a strong movement towards healthy, sustainable eating as a major component of overall ethical consumerism.

The environmental effects of different dietary patterns depend on many factors, including the proportion of animal and plant foods consumed and the method of food production. The World Health Organization has published a Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health report which was endorsed by the May 2004 World Health Assembly. It recommends the Mediterranean diet which is associated with health and longevity and is low in meat, rich in fruits and vegetables, low in added sugar and limited salt, and low in saturated fatty acids; the traditional source of fat in the Mediterranean is olive oil, rich in monounsaturated fat. The healthy rice-based Japanese diet is also high in carbohydrates and low in fat. Both diets are low in meat and saturated fats and high in legumes and other vegetables; they are associated with a low incidence of ailments and low environmental impact, at least as far as agriculture is concerned. These diets do, however, contain lots of seafood, which has a high impact on marine ecosystems.

At the global level the environmental impact of agribusiness is being addressed through sustainable agriculture and organic farming. At the local level there are various movements working towards local food production, more productive use of urban wastelands and domestic gardens including permaculture, urban horticulture, local food, slow food, sustainable gardening, and organic gardening.

Sustainable seafood is from either fished or farmed sources that can maintain or increase production in the future without jeopardizing the ecosystems from which it was acquired. The sustainable seafood movement has gained momentum as more people become aware of both overfishing and environmentally destructive fishing methods. Fish farming can also have negative environmental effects, such as the destruction of natural wetlands and marine pollution.

Materials and waste

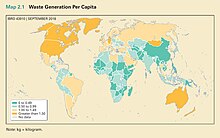

As global population and affluence have increased, so has the use of various materials increased in volume, diversity, and distance transported. Included here are raw materials, minerals, synthetic chemicals (including hazardous substances), manufactured products, food, living organisms, and waste. By 2050, humanity could consume an estimated 140 billion tons of minerals, ores, fossil fuels and biomass per year (three times its current amount) unless the economic growth rate is decoupled from the rate of natural resource consumption. Developed countries' citizens consume an average of 16 tons of those four key resources per capita per year, ranging up to 40 or more tons per person in some developed countries with resource consumption levels far beyond what is likely sustainable. By comparison, the average person in India today consumes four tons per year.

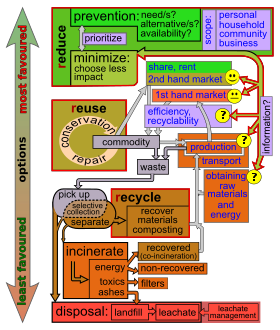

Sustainable use of materials has targeted the idea of dematerialization, converting the linear path of materials (extraction, use, disposal in landfill) to a circular material flow that reuses materials as much as possible, much like the cycling and reuse of waste in nature. Dematerialization is being encouraged through the ideas of industrial ecology, eco design and ecolabelling. The use of sustainable biomaterials that come from renewable sources and that can be recycled is preferred to the use on non-renewables from a life cycle standpoint.

This way of thinking is expressed in the concept of circular economy, which employs reuse, sharing, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing and recycling to create a closed-loop system, minimizing the use of resource inputs and the creation of waste, pollution and carbon emissions. The European Commission has adopted an ambitious Circular Economy Action Plan in 2020, which aims at making sustainable products the norm in the EU.

Human settlements

Other approaches, loosely based around New Urbanism, are successfully reducing environmental impacts by altering the built environment to create and preserve sustainable cities which support sustainable transport and zero emission housing as well as sustainable architecture and circular flow land use management.

Economic dimension

On one account, sustainability "concerns the specification of a set of actions to be taken by present persons that will not diminish the prospects of future persons to enjoy levels of consumption, wealth, utility, or welfare comparable to those enjoyed by present persons." Thus, sustainability economics means taking a long-term view of human welfare. One way of doing this is by considering the social discount rate, i.e. the rate by which future costs and benefits should be discounted when making decisions about the future. The more one is concerned about future generations, the lower the social discount rate should be. Another method is to quantify the services that ecosystems provide to humankind and put an economic value on them, so that environmental damage may be assessed against perceived short-term welfare benefits. For instance, according to the World Economic Forum, half of the global GDP is strongly or moderately dependent on nature. Also, for every dollar spent on nature restoration there is a profit of at least 9 dollars. The study of these ecosystem services is an important branch of ecological economics.

A third way in which the economic dimension of sustainability can be understood is by making a distinction between weak versus strong sustainability. In the former, loss of natural resources is compensated by an increase in human capital. Strong sustainability applies where human and natural capital are complementary, but not interchangeable. Thus, the problem of deforestation in England due to demand for wood in shipbuilding and for charcoal in iron-making was solved when ships came to be built of steel and coke replaced charcoal in iron-making – an example of weak sustainability. Prevention of biodiversity loss, which is an existential threat, is an example of the strong type. What is weak and what is strong depends partially on technology and partially on one’s convictions.

A major problem in sustainability is that many environmental and social costs are not borne by the entity that causes them, and are therefore not expressed in the market price. In economics this is known as externalities, in this case negative externalities. They can be solved by government intervention: either by taxing the activity (the polluter pays), by subsidizing activities that have a positive environmental or social effect (rewarding stewardship), or by outlawing the practice (legal limits on pollution, for instance).

In recent years, the concept of doughnut economics has been developed by the British economist Kate Raworth to integrate social and environmental sustainability into economic thinking. The social dimension is here portrayed as a minimum standard to which a society should aspire, whereas an outer limit is imposed by the carrying capacity of the planet.

Decoupling environmental degradation and economic growth

Economic opportunity

Sustainable business practices integrate ecological concerns with social and economic ones (i.e., the triple bottom line). The idea of sustainability as a business opportunity has led to the formation of organizations such as the Sustainability Consortium of the Society for Organizational Learning, the Sustainable Business Institute, and the World Council for Sustainable Development. The expansion of sustainable business opportunities can contribute to job creation through the introduction of green-collar workers. Research focusing on progressive corporate leaders who have integrated sustainability into commercial strategy has yielded a leadership competency model for sustainability, and led to emergence of the concept of "embedded sustainability"—defined by its authors Chris Laszlo and Nadya Zhexembayeva as "incorporation of environmental, health, and social value into the core business with no trade-off in price or quality—in other words, with no social or green premium." Embedded sustainability offers at least seven distinct opportunities for business value creation: better risk-management, increased efficiency through reduced waste and resource use, better product differentiation, new market entrances, enhanced brand and reputation, greater opportunity to influence industry standards, and greater opportunity for radical innovation.

Social dimension

Social sustainability is the least defined and least understood of the different ways of approaching sustainability and sustainable development. Social sustainability has had considerably less attention in public dialogue than economic and environmental sustainability. There are several approaches to sustainability. The first, which posits a triad of environmental sustainability, economic sustainability, and social sustainability, is the most widely accepted as a model for addressing sustainability. The concept of "social sustainability" in this approach encompasses such topics as: social equity, livability, health equity, community development, social capital, social support, human rights, labour rights, placemaking, social responsibility, social justice, cultural competence, community resilience, and human adaptation.

A second approach suggests that all of the domains of sustainability are social: including ecological, economic, political and cultural sustainability. These domains of social sustainability are all dependent upon the relationship between the social and the natural, with the "ecological domain" defined as human embeddedness in the environment. In these terms, social sustainability encompasses all human activities. It is not just relevant to the focussed intersection of economics, the environment and the social.Broad-based strategies for more sustainable social systems include: improved education and the political empowerment of women, especially in developing countries; greater regard for social justice, notably equity between rich and poor both within and between countries; and, perhaps most of all, intergenerational equity. After all, to be sustained means to outlast the present.

Peace, security, social justice

Social disruptions like war, crime and corruption divert resources from areas of greatest human need, damage the capacity of societies to plan for the future, and generally threaten human well-being and the environment.

Cultural dimension

Health and wellbeing

The World Health Organization recognizes that achieving sustainability is impossible without addressing health issues. There is a rise in some interconnected health and sustainability problems, for example, in food production. Measures for achieving environmental sustainability can in many cases also improve health.

For better measuring the well-being, the New Economics Foundation's has launched the Happy Planet Index. In the beginning of the 21st century, more than 100 organizations created the Wellbeing Economy Alliance with the aim to create an economy that will guarantee well-being and heal nature at the same time.

Religion

Within the context of Christianity, in the encyclical "Laudato si'", Pope Francis called to fight climate change and ecological degradation as a whole. He claimed that humanity is facing a severe ecological crisis and blamed consumerism and irresponsible development. The encyclical is addressed to "every person living on this planet."

Buddhism includes many principles linked to sustainability. The Dalai Lama has consistently called for strong climate action, reforestation, preserving ecosystems, a reduction in meat consumption. He declared that if he will ever join a political party it will be the green party and if Buddha returned to our world now: “Buddha would be green.” The leaders of Buddhism issued a special declaration calling on all believers to fight climate change and environmental destruction as a whole.

Threats

There are at least three letters from the scientific community about the growing threat to sustainability and ways to remove the threat.

- In 1992, scientists wrote the first World Scientists' Warning to Humanity, which begins: "Human beings and the natural world are on a collision course." About 1,700 of the world's leading scientists, including most Nobel Prize laureates in the sciences, signed it. The letter mentions severe damage to atmosphere, oceans, ecosystems, soil productivity, and more. It warns humanity that life on earth as we know it can become impossible, and if humanity wants to prevent the damage, some steps need to be taken: better use of resources, abandon of fossil fuels, stabilization of human population, elimination of poverty and more.

- In 2017, the scientists wrote a second warning to humanity. In this warning, the scientists mention some positive trends like slowing deforestation, but despite this, they claim that except ozone depletion, none of the problems mentioned in the first warning received an adequate response. The scientists called to reduce the use of fossil fuels, meat, and other resources and to stabilize the population. It was signed by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries, making it the letter with the most scientist signatures in history.

- In November 2019, more than 11,000 scientists from 153 countries published a letter in which they warn about serious threats to sustainability from climate change unless big changes in policies happen. The scientists declared "climate emergency" and called to stop overconsumption, move away from fossil fuels, eat less meat, stabilize the population, and more.

In 2009 a group of scientists led by Johan Rockström from the Stockholm Resilience Centre and Will Steffen from the Australian National University described nine planetary boundaries. Transgressing even one of them can be dangerous to sustainability. Those boundaries are climate change, biodiversity loss (changed in 2015 to "change in biosphere integrity"), biogeochemical (nitrogen and phosphorus), ocean acidification, land use, freshwater, ozone depletion, atmospheric aerosols, chemical pollution (changed in 2015 to "Introduction of novel entities").

Similarly, in 2005, 12 main problems were described that can be dangerous to sustainability: Deforestation and habitat destruction, soil problems (erosion, salinization, and soil fertility losses), water management problems, overhunting, overfishing, effects of introduced species on native species, overpopulation, Increased per-capita impact of people, climate change, Buildup of toxins in the environment, energy shortages, full human use of the Earth's photosynthetic capacity.

In 2021 the United Nations Environment Programme issued a report describing three major environmental threats to sustainability: climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution. The report states that as of the year 2021 humanity fails to properly address the main environmental challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic is also linked to environmental issues, including climate change, deforestation and wildlife trade.

Ecosystems and biodiversity

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment analyzed the state of the Earth's ecosystems and provides summaries and guidelines for decision-makers. It concludes that human activity is having a significant and escalating impact on the biodiversity of the world ecosystems, reducing both their resilience and biocapacity. The report refers to natural systems as humanity's "life-support system", providing essential "ecosystem services". The assessment measures 24 ecosystem services and concludes that only four have shown improvement over the last 50 years, 15 are in serious decline, and five are in a precarious condition.

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. It recommends that human civilization will need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management.

Solutions: paths to sustainability

Affluence, population and technology

Strategies for reaching sustainability can generally be divided into three categories. Most governments and international organizations that aim to achieve sustainability employ all three approaches, though they may disagree on which deserves priority. The three approaches, embodied in the I = PAT formula, can be summarized as follows:

Affluence: Many believe that sustainability cannot be achieved without reducing consumption. This theory is represented most clearly in the idea of a steady-state economy, meaning an economy without growth. Methods in this category include, among others, the phase-out of lightweight plastic bags, promoting biking, and increasing energy efficiency. For example, according to the report "Plastic and Climate", plastic-production greenhouse gas emissions can be as much as 15% of earth's remaining carbon budget by 2050 and over 50% by 2100, except the impacts on phytoplankton. The report says that for solving the problem, reduction in consumption will be essential. In 2020, scientific research published by the World Economic Forum determined that affluence is the biggest threat to sustainability.

Population: Others think that the most effective means of achieving sustainability is population control, for example by improving access to birth control and education (particularly education for girls). Fertility rates are known to decline with increased prosperity, and have been declining globally since 1980.

Technology: Still others hold that the most promising path to sustainability is new technology. This theory may be seen as a form of technological optimism. One popular tactic in this category is transitioning to renewable energy. Others methods to achieve sustainability, associated with this theory are climate engineering (geo – engineering), genetic engineering (GMO, Genetically modified organism), decoupling.

History

The history of sustainability traces human-dominated ecological systems from the earliest civilizations to the present day. This history is characterized by the increased regional success of a particular society, followed by crises that were either resolved, producing sustainability, or not, leading to decline. In early human history, the use of fire and desire for specific foods may have altered the natural composition of plant and animal communities. Between 8,000 and 12,000 years ago, agrarian communities emerged which depended largely on their environment and the creation of a "structure of permanence."

The Western industrial revolution of the 18th to 19th centuries tapped into the vast growth potential of the energy in fossil fuels. Coal was used to power ever more efficient engines and later to generate electricity. Modern sanitation systems and advances in medicine protected large populations from disease. In the mid-20th century, a gathering environmental movement pointed out that there were environmental costs associated with the many material benefits that were now being enjoyed. In the late 20th century, environmental problems became global in scale. The 1973 and 1979 energy crises demonstrated the extent to which the global community had become dependent on non-renewable energy resources. By the 1970s, the ecological footprint of humanity exceeded the carrying capacity of earth, therefore the mode of life of humanity became unsustainable. In the 21st century, there is increasing global awareness of the threat posed by global climate change, produced largely by the burning of fossil fuels. Another major threat is biodiversity loss, caused primarily by land use change.