| |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Pharmacist, Chemist, Doctor of Pharmacy, Druggist, Apothecary or simply Doctor |

Occupation type | Professional |

Activity sectors | Health care, health sciences, chemical sciences |

| Description | |

Education required | Doctor of Pharmacy, Master of Pharmacy, Bachelor of Pharmacy, Diploma in Pharmacy |

Related jobs | Physician, pharmacy technician, toxicologist, chemist, pharmacy assistant, other medical specialists |

Pharmacy is the clinical health science that links medical science with chemistry and it is charged with the discovery, production, disposal, safe and effective use, and control of medications and drugs. The practice of pharmacy requires excellent knowledge of drugs, their mechanism of action, side effects, interactions, mobility and toxicity. At the same time, it requires knowledge of treatment and understanding of the pathological process. Some specialties of pharmacists, such as that of clinical pharmacists, require other skills, e.g. knowledge about the acquisition and evaluation of physical and laboratory data.

The scope of pharmacy practice includes more traditional roles such as compounding and dispensing of medications, and it also includes more modern services related to health care, including clinical services, reviewing medications for safety and efficacy, and providing drug information. Pharmacists, therefore, are the experts on drug therapy and are the primary health professionals who optimize the use of medication for the benefit of the patients.

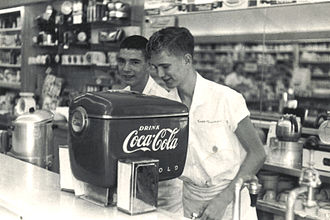

An establishment in which pharmacy (in the first sense) is practiced is called a pharmacy (this term is more common in the United States) or a chemist's (which is more common in Great Britain, though pharmacy is also used). In the United States and Canada, drugstores commonly sell medicines, as well as miscellaneous items such as confectionery, cosmetics, office supplies, toys, hair care products and magazines, and occasionally refreshments and groceries.

In its investigation of herbal and chemical ingredients, the work of the apothecary may be regarded as a precursor of the modern sciences of chemistry and pharmacology, prior to the formulation of the scientific method.

Disciplines

The field of pharmacy can generally be divided into three primary disciplines:

- Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy

- Pharmacy Practice

The boundaries between these disciplines and with other sciences, such as biochemistry, are not always clear-cut. Often, collaborative teams from various disciplines (pharmacists and other scientists) work together toward the introduction of new therapeutics and methods for patient care. However, pharmacy is not a basic or biomedical science in its typical form. Medicinal chemistry is also a distinct branch of synthetic chemistry combining pharmacology, organic chemistry, and chemical biology.

Pharmacology is sometimes considered as the fourth discipline of pharmacy. Although pharmacology is essential to the study of pharmacy, it is not specific to pharmacy. Both disciplines are distinct. Those who wish to practice both pharmacy (patient-oriented) and pharmacology (a biomedical science requiring the scientific method) receive separate training and degrees unique to either discipline.

Pharmacoinformatics is considered another new discipline, for systematic drug discovery and development with efficiency and safety.

Pharmacogenomics is the study of genetic-linked variants that effect patient clinical responses, allergies, and metabolism of drugs.

Professionals

The World Health Organization estimates that there are at least 2.6 million pharmacists and other pharmaceutical personnel worldwide.

Pharmacists

Pharmacists are healthcare professionals with specialized education and training who perform various roles to ensure optimal health outcomes for their patients through the quality use of medicines. Pharmacists may also be small business proprietors, owning the pharmacy in which they practice. Since pharmacists know about the mode of action of a particular drug, and its metabolism and physiological effects on the human body in great detail, they play an important role in optimization of drug treatment for an individual.

Pharmacists are represented internationally by the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). They are represented at the national level by professional organisations such as the Royal Pharmaceutical Society in the UK, Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA), Indian Pharmacist Association (IPA), Pakistan Pharmacists Association (PPA), American Pharmacists Association (APhA), and the Malaysian Pharmaceutical Society (MPS).

In some cases, the representative body is also the registering body, which is responsible for the regulation and ethics of the profession.

In the United States, specializations in pharmacy practice recognized by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties include: cardiovascular, infectious disease, oncology, pharmacotherapy, nuclear, nutrition, and psychiatry. The Commission for Certification in Geriatric Pharmacy certifies pharmacists in geriatric pharmacy practice. The American Board of Applied Toxicology certifies pharmacists and other medical professionals in applied toxicology.

Pharmacy support staff

Pharmacy technicians

Pharmacy technicians support the work of pharmacists and other health professionals by performing a variety of pharmacy-related functions, including dispensing prescription drugs and other medical devices to patients and instructing on their use. They may also perform administrative duties in pharmaceutical practice, such as reviewing prescription requests with medic's offices and insurance companies to ensure correct medications are provided and payment is received.

Legislation requires the supervision of certain pharmacy technician's activities by a pharmacist. The majority of pharmacy technicians work in community pharmacies. In hospital pharmacies, pharmacy technicians may be managed by other senior pharmacy technicians. In the UK the role of a PhT in hospital pharmacy has grown and responsibility has been passed on to them to manage the pharmacy department and specialized areas in pharmacy practice allowing pharmacists the time to specialize in their expert field as medication consultants spending more time working with patients and in research. Pharmacy technicians are registered with the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC). The GPhC is the regulator of pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and pharmacy premises.

In the US, pharmacy technicians perform their duties under the supervision of pharmacists. Although they may perform, under supervision, most dispensing, compounding and other tasks, they are not generally allowed to perform the role of counseling patients on the proper use of their medications. Some states have a legally mandated pharmacist-to-pharmacy technician ratio.

Dispensing assistants

Dispensing assistants are commonly referred to as "dispensers" and in community pharmacies perform largely the same tasks as a pharmacy technician. They work under the supervision of pharmacists and are involved in preparing (dispensing and labelling) medicines for provision to patients.

Healthcare assistants/medicines counter assistants

In the UK, this group of staff can sell certain medicines (including pharmacy only and general sales list medicines) over the counter. They cannot prepare prescription-only medicines for supply to patients.

Education requirements

There are different requirements of schooling according to the national jurisdiction where the student intends to practise.

United States

In the United States, general pharmacist will attain a Doctor of Pharmacy Degree (Pharm.D.). The Pharm.D. can be completed in a minimum of six years, which includes two years of pre-pharmacy classes, and four years of professional studies. After graduating pharmacy school, it is highly suggested that the student go on to complete a one or two-year residency, which provides valuable experience for the student before going out independently to be a generalized or specialized pharmacist.

The curriculum specified for a Pharm.D. consists of at least 208-credit hours. Of the 208 credit hours, 68 are transferred-credit hours, and the remaining 140 credit hours are completed in the professional school. There are a series of required standardized tests that students have to pass throughout the process of pharmacy school. The standardized test to get into pharmacy school in the United States is called the Pharmacy College Admission Test (PCAT). In a student's third professional year in pharmacy school, it is required to pass the Pharmacy Curriculum Outcomes Assessment (PCOA). Once the Pharm.D. is attained after the fourth year of professional school, the student is then eligible to take the North American Pharmacist Licensure Exam (NAPLEX) and the Multistate Pharmacy Jurisprudence Exam (MPJE) to work as a professional pharmacist.

History

The earliest known compilation of medicinal substances was the Sushruta Samhita, an Indian Ayurvedic treatise attributed to Sushruta in the 6th century BC. However, the earliest text as preserved dates to the 3rd or 4th century AD.

Many Sumerian (4th millennium BC – early 2nd millennium BC) cuneiform clay tablets record prescriptions for medicine.

Ancient Egyptian pharmacological knowledge was recorded in various papyri such as the Ebers Papyrus of 1550 BC, and the Edwin Smith Papyrus of the 16th century BC.

In Ancient Greece, Diocles of Carystus (4th century BC) was one of several men studying the medicinal properties of plants. He wrote several treatises on the topic. The Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides is famous for writing a five-volume book in his native Greek Περί ύλης ιατρικής in the 1st century AD. The Latin translation De Materia Medica (Concerning medical substances) was used as a basis for many medieval texts and was built upon by many middle eastern scientists during the Islamic Golden Age, themselves deriving their knowledge from earlier Greek Byzantine medicine Byzantine Medicine.

Pharmacy in China dates at least to the earliest known Chinese manual, the Shennong Bencao Jing (The Divine Farmer's Herb-Root Classic), dating back to the 1st century AD. It was compiled during the Han dynasty and was attributed to the mythical Shennong. Earlier literature included lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by a manuscript "Recipes for 52 Ailments", found in the Mawangdui, sealed in 168 BC.

In Japan, at the end of the Asuka period (538–710) and the early Nara period (710–794), the men who fulfilled roles similar to those of modern pharmacists were highly respected. The place of pharmacists in society was expressly defined in the Taihō Code (701) and re-stated in the Yōrō Code (718). Ranked positions in the pre-Heian Imperial court were established; and this organizational structure remained largely intact until the Meiji Restoration (1868). In this highly stable hierarchy, the pharmacists—and even pharmacist assistants—were assigned status superior to all others in health-related fields such as physicians and acupuncturists. In the Imperial household, the pharmacist was even ranked above the two personal physicians of the Emperor.

There is a stone sign for a pharmacy shop with a tripod, a mortar, and a pestle opposite one for a doctor in the Arcadian Way in Ephesus near Kusadasi in Turkey. The current Ephesus dates back to 400 BC and was the site of the Temple of Artemis, one of the seven wonders of the world.

In Baghdad the first pharmacies, or drug stores, were established in 754, under the Abbasid Caliphate during the Islamic Golden Age. By the 9th century, these pharmacies were state-regulated.

The advances made in the Middle East in botany and chemistry led medicine in medieval Islam substantially to develop pharmacology. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) (865–915), for instance, acted to promote the medical uses of chemical compounds. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (Abulcasis) (936–1013) pioneered the preparation of medicines by sublimation and distillation. His Liber servitoris is of particular interest, as it provides the reader with recipes and explains how to prepare the 'simples' from which were compounded the complex drugs then generally used. Sabur Ibn Sahl (d 869), was, however, the first physician to record his findings in a pharmacopoeia, describing a large variety of drugs and remedies for ailments. Al-Biruni (973–1050) wrote one of the most valuable Islamic works on pharmacology, entitled Kitab al-Saydalah (The Book of Drugs), in which he detailed the properties of drugs and outlined the role of pharmacy and the functions and duties of the pharmacist. Avicenna, too, described no less than 700 preparations, their properties, modes of action, and their indications. He devoted in fact a whole volume to simple drugs in The Canon of Medicine. Of great impact were also the works by al-Maridini of Baghdad and Cairo, and Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074), both of which were printed in Latin more than fifty times, appearing as De Medicinis universalibus et particularibus by 'Mesue' the younger, and the Medicamentis simplicibus by 'Abenguefit'. Peter of Abano (1250–1316) translated and added a supplement to the work of al-Maridini under the title De Veneris. Al-Muwaffaq's contributions in the field are also pioneering. Living in the 10th century, he wrote The foundations of the true properties of Remedies, amongst others describing arsenious oxide, and being acquainted with silicic acid. He made clear distinction between sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate, and drew attention to the poisonous nature of copper compounds, especially copper vitriol, and also lead compounds. He also describes the distillation of sea-water for drinking.

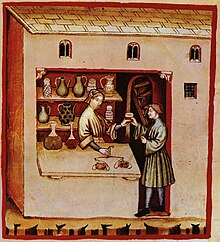

In Europe, pharmacy-like shops began to appear during the 12th century. In 1240, emperor Frederic II issued a decree by which the physician's and the apothecary's professions were separated.

There are pharmacies in Europe that have been in operation since medieval times. In Dubrovnik (Croatia), a pharmacy that first opened in 1317 is located inside the Franciscan monastery: it is oldest operating pharmacy in Europe. In the Town Hall Square of Tallinn (Estonia), there is a pharmacy dating from at least 1422. The medieval Esteve Pharmacy, located in Llívia, a Catalan enclave close to Puigcerdà, is a museum: the building dates back to the 15th century and the museum keeps albarellos from the 16th and 17th centuries, old prescription books and antique drugs.

Practice areas

Pharmacists practice in a variety of areas including community pharmacies, hospitals, clinics, extended care facilities, psychiatric hospitals, and regulatory agencies. Pharmacists themselves may have expertise in a medical specialty.

Community pharmacy

A pharmacy (also known as a chemist in Australia, New Zealand and the British Isles; or drugstore in North America; retail pharmacy in industry terminology; or apothecary, historically) is where most pharmacists practice the profession of pharmacy. It is the community pharmacy in which the dichotomy of the profession exists; health professionals who are also retailers.

Community pharmacies usually consist of a retail storefront with a dispensary, where medications are stored and dispensed. According to Sharif Kaf al-Ghazal, the opening of the first drugstores are recorded by Muslim pharmacists in Baghdad in 754 AD.

Hospital pharmacy

Pharmacies within hospitals differ considerably from community pharmacies. Some pharmacists in hospital pharmacies may have more complex clinical medication management issues, and pharmacists in community pharmacies often have more complex business and customer relations issues.

Because of the complexity of medications including specific indications, effectiveness of treatment regimens, safety of medications (i.e., drug interactions) and patient compliance issues (in the hospital and at home), many pharmacists practicing in hospitals gain more education and training after pharmacy school through a pharmacy practice residency, sometimes followed by another residency in a specific area. Those pharmacists are often referred to as clinical pharmacists and they often specialize in various disciplines of pharmacy.

For example, there are pharmacists who specialize in hematology/oncology, HIV/AIDS, infectious disease, critical care, emergency medicine, toxicology, nuclear pharmacy, pain management, psychiatry, anti-coagulation clinics, herbal medicine, neurology/epilepsy management, pediatrics, neonatal pharmacists and more.

Hospital pharmacies can often be found within the premises of the hospital. Hospital pharmacies usually stock a larger range of medications, including more specialized medications, than would be feasible in the community setting. Most hospital medications are unit-dose, or a single dose of medicine. Hospital pharmacists and trained pharmacy technicians compound sterile products for patients including total parenteral nutrition (TPN), and other medications are given intravenously. That is a complex process that requires adequate training of personnel, quality assurance of products, and adequate facilities.

Several hospital pharmacies have decided to outsource high-risk preparations and some other compounding functions to companies who specialize in compounding. The high cost of medications and drug-related technology and the potential impact of medications and pharmacy services on patient-care outcomes and patient safety require hospital pharmacies to perform at the highest level possible.

Clinical pharmacy

Pharmacists provide direct patient care services that optimize the use of medication and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention. Clinical pharmacists care for patients in all health care settings, but the clinical pharmacy movement initially began inside hospitals and clinics. Clinical pharmacists often collaborate with physicians and other healthcare professionals to improve pharmaceutical care. Clinical pharmacists are now an integral part of the interdisciplinary approach to patient care. They often participate in patient care rounds for drug product selection. In the UK clinical pharmacists can also prescribe some medications for patients on the NHS or privately, after completing a non-medical prescribers course to become an Independent Prescriber.

The clinical pharmacist's role involves creating a comprehensive drug therapy plan for patient-specific problems, identifying goals of therapy, and reviewing all prescribed medications prior to dispensing and administration to the patient. The review process often involves an evaluation of the appropriateness of drug therapy (e.g., drug choice, dose, route, frequency, and duration of therapy) and its efficacy. The pharmacist must also consider potential drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, and patient drug allergies while they design and initiate a drug therapy plan.

Ambulatory care pharmacy

Since the emergence of modern clinical pharmacy, ambulatory care pharmacy practice has emerged as a unique pharmacy practice setting. Ambulatory care pharmacy is based primarily on pharmacotherapy services that a pharmacist provides in a clinic. Pharmacists in this setting often do not dispense drugs, but rather see patients in-office visits to manage chronic disease states.

In the U.S. federal health care system (including the VA, the Indian Health Service, and NIH) ambulatory care pharmacists are given full independent prescribing authority. In some states, such North Carolina and New Mexico, these pharmacist clinicians are given collaborative prescriptive and diagnostic authority. In 2011 the board of Pharmaceutical Specialties approved ambulatory care pharmacy practice as a separate board certification. The official designation for pharmacists who pass the ambulatory care pharmacy specialty certification exam will be Board Certified Ambulatory Care Pharmacist and these pharmacists will carry the initials BCACP.

Compounding pharmacy/industrial pharmacy

Compounding involves preparing drugs in forms that are different from the generic prescription standard. This may include altering the strength, ingredients, or dosage form. Compounding is a way to create custom drugs for patients who may not be able to take the medication in its standard form, such as due to an allergy or difficulty swallowing. Compounding is necessary for these patients to still be able to properly get the prescriptions they need.

One area of compounding is preparing drugs in new dosage forms. For example, if a drug manufacturer only provides a drug as a tablet, a compounding pharmacist might make a medicated lollipop that contains the drug. Patients who have difficulty swallowing the tablet may prefer to suck the medicated lollipop instead.

Another form of compounding is by mixing different strengths (g, mg, mcg) of capsules or tablets to yield the desired amount of medication indicated by the physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, or clinical pharmacist practitioner. This form of compounding is found at community or hospital pharmacies or in-home administration therapy.

Compounding pharmacies specialize in compounding, although many also dispense the same non-compounded drugs that patients can obtain from community pharmacies.

Consultant pharmacy

Consultant pharmacy practice focuses more on medication regimen review (i.e. "cognitive services") than on actual dispensing of drugs. Consultant pharmacists most typically work in nursing homes, but are increasingly branching into other institutions and non-institutional settings. Traditionally consultant pharmacists were usually independent business owners, though in the United States many now work for a large pharmacy management company such as Omnicare, Kindred Healthcare or PharMerica. This trend may be gradually reversing as consultant pharmacists begin to work directly with patients, primarily because many elderly people are now taking numerous medications but continue to live outside of institutional settings. Some community pharmacies employ consultant pharmacists and/or provide consulting services.

The main principle of consultant pharmacy is developed by Hepler and Strand in 1990.

Veterinary pharmacy

Veterinary pharmacies, sometimes called animal pharmacies, may fall in the category of hospital pharmacy, retail pharmacy or mail-order pharmacy. Veterinary pharmacies stock different varieties and different strengths of medications to fulfill the pharmaceutical needs of animals. Because the needs of animals, as well as the regulations on veterinary medicine, are often very different from those related to people, in some jurisdictions veterinary pharmacy may be kept separate from regular pharmacies.

Nuclear pharmacy

Nuclear pharmacy focuses on preparing radioactive materials for diagnostic tests and for treating certain diseases. Nuclear pharmacists undergo additional training specific to handling radioactive materials, and unlike in community and hospital pharmacies, nuclear pharmacists typically do not interact directly with patients.

Military pharmacy

Military pharmacy is a different working environment to civilian practise because military pharmacy technicians perform duties such as evaluating medication orders, preparing medication orders, and dispensing medications. This would be illegal in civilian pharmacies because these duties are required to be performed by a licensed registered pharmacist. In the US military, state laws that prevent technicians from counseling patients or doing the final medication check prior to dispensing to patients (rather than a pharmacist solely responsible for these duties) do not apply.

Pharmacy informatics

Pharmacy informatics is the combination of pharmacy practice science and applied information science. Pharmacy informaticists work in many practice areas of pharmacy, however, they may also work in information technology departments or for healthcare information technology vendor companies. As a practice area and specialist domain, pharmacy informatics is growing quickly to meet the needs of major national and international patient information projects and health system interoperability goals. Pharmacists in this area are trained to participate in medication management system development, deployment, and optimization.

Specialty pharmacy

Specialty pharmacies supply high-cost injectable, oral, infused, or inhaled medications that are used for chronic and complex disease states such as cancer, hepatitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Unlike a traditional community pharmacy where prescriptions for any common medication can be brought in and filled, specialty pharmacies carry novel medications that need to be properly stored, administered, carefully monitored, and clinically managed. In addition to supplying these drugs, specialty pharmacies also provide lab monitoring, adherence counseling, and assist patients with cost-containment strategies needed to obtain their expensive specialty drugs. In the US, it is currently the fastest-growing sector of the pharmaceutical industry with 19 of 28 newly FDA approved medications in 2013 being specialty drugs.

Due to the demand for clinicians who can properly manage these specific patient populations, the Specialty Pharmacy Certification Board has developed a new certification exam to certify specialty pharmacists. Along with the 100 questions computerized multiple-choice exam, pharmacists must also complete 3,000 hours of specialty pharmacy practice within the past three years as well as 30 hours of specialty pharmacist continuing education within the past two years.

Pharmaceutical sciences

The pharmaceutical sciences are a group of interdisciplinary areas of study concerned with the design, action, delivery, and disposition of drugs. They apply knowledge from chemistry (inorganic, physical, biochemical and analytical), biology (anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, cell biology, and molecular biology), epidemiology, statistics, chemometrics, mathematics, physics, and chemical engineering.

The pharmaceutical sciences are further subdivided into several specific specialties, with four main branches:

- Pharmacology: the study of the biochemical and physiological effects of drugs on human beings.

- Pharmacodynamics: the study of the cellular and molecular interactions of drugs with their receptors. Simply "What the drug does to the body"

- Pharmacokinetics: the study of the factors that control the concentration of drug at various sites in the body. Simply "What the body does to the drug"

- Pharmaceutical toxicology: the study of the harmful or toxic effects of drugs.

- Pharmacogenomics: the study of the inheritance of characteristic patterns of interaction between drugs and organisms.

- Pharmaceutical chemistry: the study of drug design to optimize pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and synthesis of new drug molecules (Medicinal Chemistry).

- Pharmaceutics: the study and design of drug formulation for optimum delivery, stability, pharmacokinetics, and patient acceptance.

- Pharmacognosy: the study of medicines derived from natural sources.

As new discoveries advance and extend the pharmaceutical sciences, subspecialties continue to be added to this list. Importantly, as knowledge advances, boundaries between these specialty areas of pharmaceutical sciences are beginning to blur. Many fundamental concepts are common to all pharmaceutical sciences. These shared fundamental concepts further the understanding of their applicability to all aspects of pharmaceutical research and drug therapy.

Pharmacocybernetics (also known as pharma-cybernetics, cybernetic pharmacy, and cyber pharmacy) is an emerging field that describes the science of supporting drugs and medications use through the application and evaluation of informatics and internet technologies, so as to improve the pharmaceutical care of patients.

Society and culture

Etymology

The word pharmacy is derived from Old French farmacie "substance, such as a food or in the form of a medicine which has a laxative effect" from Medieval Latin pharmacia from Greek pharmakeia (Greek: φαρμακεία) "a medicine", which itself derives from pharmakon (φάρμακον), meaning "drug, poison, spell" (which is etymologically related to pharmakos).

Separation of prescribing and dispensing

Separation of prescribing and dispensing, also called dispensing separation, is a practice in medicine and pharmacy in which the physician who provides a medical prescription is independent from the pharmacist who provides the prescription drug.

In the Western world there are centuries of tradition for separating pharmacists from physicians. In Asian countries, it is traditional for physicians to also provide drugs.

In contemporary time researchers and health policy analysts have more deeply considered these traditions and their effects. Advocates for separation and advocates for combining make similar claims for each of their conflicting perspectives, saying that separating or combining reduces conflict of interest in the healthcare industry, unnecessary health care, and lowers costs, while the opposite causes those things. Research in various places reports mixed outcomes in different circumstances.

The future of pharmacy

In the coming decades, pharmacists are expected to become more integral within the health care system. Rather than simply dispensing medication, pharmacists are increasingly expected to be compensated for their patient care skills. In particular, Medication Therapy Management (MTM) includes the clinical services that pharmacists can provide for their patients. Such services include a thorough analysis of all medication (prescription, non-prescription, and herbals) currently being taken by an individual. The result is a reconciliation of medication and patient education resulting in increased patient health outcomes and decreased costs to the health care system.

This shift has already commenced in some countries; for instance, pharmacists in Australia receive remuneration from the Australian Government for conducting comprehensive Home Medicines Reviews. In Canada, pharmacists in certain provinces have limited prescribing rights (as in Alberta and British Columbia) or are remunerated by their provincial government for expanded services such as medications reviews (Medschecks in Ontario). In the United Kingdom, pharmacists who undertake additional training are obtaining prescribing rights and this is because of pharmacy education. They are also being paid for by the government for medicine use reviews. In Scotland, the pharmacist can write prescriptions for Scottish registered patients of their regular medications, for the majority of drugs, except for controlled drugs, when the patient is unable to see their doctor, as could happen if they are away from home or the doctor is unavailable. In the United States, pharmaceutical care or clinical pharmacy has had an evolving influence on the practice of pharmacy. Moreover, the Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm. D.) degree is now required before entering practice and some pharmacists now complete one or two years of residency or fellowship training following graduation. In addition, consultant pharmacists, who traditionally operated primarily in nursing homes, are now expanding into direct consultation with patients, under the banner of "senior care pharmacy".

In addition to patient care, pharmacies will be a focal point for medical adherence initiatives. There is enough evidence to show that integrated pharmacy based initiatives significantly impact adherence for chronic patients. For example, a study published in NIH shows "pharmacy based interventions improved patients' medication adherence rates by 2.1 percent and increased physicians' initiation rates by 38 percent, compared to the control group".