Cellular differentiation is the process in which a cell changes from one cell type to another. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation occurs numerous times during the development of a multicellular organism as it changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of tissues and cell types. Differentiation continues in adulthood as adult stem cells divide and create fully differentiated daughter cells during tissue repair and during normal cell turnover. Some differentiation occurs in response to antigen exposure. Differentiation dramatically changes a cell's size, shape, membrane potential, metabolic activity, and responsiveness to signals. These changes are largely due to highly controlled modifications in gene expression and are the study of epigenetics. With a few exceptions, cellular differentiation almost never involves a change in the DNA sequence itself. Although metabolic composition does get altered quite dramatically where stem cells are characterized by abundant metabolites with highly unsaturated structures whose levels decrease upon differentiation. Thus, different cells can have very different physical characteristics despite having the same genome.

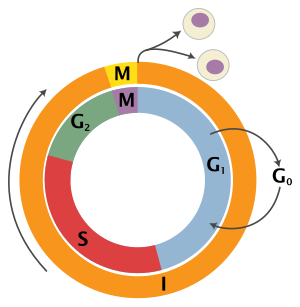

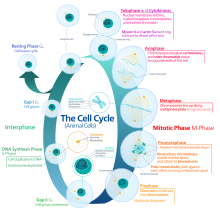

A specialized type of differentiation, known as terminal differentiation, is of importance in some tissues, for example vertebrate nervous system, striated muscle, epidermis and gut. During terminal differentiation, a precursor cell formerly capable of cell division, permanently leaves the cell cycle, dismantles the cell cycle machinery and often expresses a range of genes characteristic of the cell's final function (e.g. myosin and actin for a muscle cell). Differentiation may continue to occur after terminal differentiation if the capacity and functions of the cell undergo further changes.

Among dividing cells, there are multiple levels of cell potency, the cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types. A greater potency indicates a larger number of cell types that can be derived. A cell that can differentiate into all cell types, including the placental tissue, is known as totipotent. In mammals, only the zygote and subsequent blastomeres are totipotent, while in plants, many differentiated cells can become totipotent with simple laboratory techniques. A cell that can differentiate into all cell types of the adult organism is known as pluripotent. Such cells are called meristematic cells in higher plants and embryonic stem cells in animals, though some groups report the presence of adult pluripotent cells. Virally induced expression of four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 (Yamanaka factors) is sufficient to create pluripotent (iPS) cells from adult fibroblasts. A multipotent cell is one that can differentiate into multiple different, but closely related cell types. Oligopotent cells are more restricted than multipotent, but can still differentiate into a few closely related cell types. Finally, unipotent cells can differentiate into only one cell type, but are capable of self-renewal. In cytopathology, the level of cellular differentiation is used as a measure of cancer progression. "Grade" is a marker of how differentiated a cell in a tumor is.

Mammalian cell types

Three basic categories of cells make up the mammalian body: germ cells, somatic cells, and stem cells. Each of the approximately 37.2 trillion (3.72x1013) cells in an adult human has its own copy or copies of the genome except certain cell types, such as red blood cells, that lack nuclei in their fully differentiated state. Most cells are diploid; they have two copies of each chromosome. Such cells, called somatic cells, make up most of the human body, such as skin and muscle cells. Cells differentiate to specialize for different functions.

Germ line cells are any line of cells that give rise to gametes—eggs and sperm—and thus are continuous through the generations. Stem cells, on the other hand, have the ability to divide for indefinite periods and to give rise to specialized cells. They are best described in the context of normal human development.

Development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg and creates a single cell that has the potential to form an entire organism. In the first hours after fertilization, this cell divides into identical cells. In humans, approximately four days after fertilization and after several cycles of cell division, these cells begin to specialize, forming a hollow sphere of cells, called a blastocyst. The blastocyst has an outer layer of cells, and inside this hollow sphere, there is a cluster of cells called the inner cell mass. The cells of the inner cell mass go on to form virtually all of the tissues of the human body. Although the cells of the inner cell mass can form virtually every type of cell found in the human body, they cannot form an organism. These cells are referred to as pluripotent.

Pluripotent stem cells undergo further specialization into multipotent progenitor cells that then give rise to functional cells. Examples of stem and progenitor cells include:

- Radial glial cells (embryonic neural stem cells) that give rise to excitatory neurons in the fetal brain through the process of neurogenesis.

- Hematopoietic stem cells (adult stem cells) from the bone marrow that give rise to red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- Mesenchymal stem cells (adult stem cells) from the bone marrow that give rise to stromal cells, fat cells, and types of bone cells

- Epithelial stem cells (progenitor cells) that give rise to the various types of skin cells

- Muscle satellite cells (progenitor cells) that contribute to differentiated muscle tissue.

A pathway that is guided by the cell adhesion molecules consisting of four amino acids, arginine, glycine, asparagine, and serine, is created as the cellular blastomere differentiates from the single-layered blastula to the three primary layers of germ cells in mammals, namely the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm (listed from most distal (exterior) to proximal (interior)). The ectoderm ends up forming the skin and the nervous system, the mesoderm forms the bones and muscular tissue, and the endoderm forms the internal organ tissues.

Dedifferentiation

Dedifferentiation, or integration, is a cellular process often seen in more basal life forms such as worms and amphibians in which a partially or terminally differentiated cell reverts to an earlier developmental stage, usually as part of a regenerative process. Dedifferentiation also occurs in plants. Cells in cell culture can lose properties they originally had, such as protein expression, or change shape. This process is also termed dedifferentiation.

Some believe dedifferentiation is an aberration of the normal development cycle that results in cancer, whereas others believe it to be a natural part of the immune response lost by humans at some point as a result of evolution.

A small molecule dubbed reversine, a purine analog, has been discovered that has proven to induce dedifferentiation in myotubes. These dedifferentiated cells could then redifferentiate into osteoblasts and adipocytes.

Mechanisms

Each specialized cell type in an organism expresses a subset of all the genes that constitute the genome of that species. Each cell type is defined by its particular pattern of regulated gene expression. Cell differentiation is thus a transition of a cell from one cell type to another and it involves a switch from one pattern of gene expression to another. Cellular differentiation during development can be understood as the result of a gene regulatory network. A regulatory gene and its cis-regulatory modules are nodes in a gene regulatory network; they receive input and create output elsewhere in the network. The systems biology approach to developmental biology emphasizes the importance of investigating how developmental mechanisms interact to produce predictable patterns (morphogenesis). However, an alternative view has been proposed recently. Based on stochastic gene expression, cellular differentiation is the result of a Darwinian selective process occurring among cells. In this frame, protein and gene networks are the result of cellular processes and not their cause.

While evolutionarily conserved molecular processes are involved in the cellular mechanisms underlying these switches, in animal species these are very different from the well-characterized gene regulatory mechanisms of bacteria, and even from those of the animals' closest unicellular relatives. Specifically, cell differentiation in animals is highly dependent on biomolecular condensates of regulatory proteins and enhancer DNA sequences.

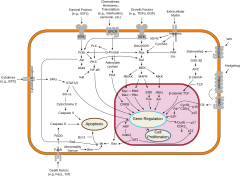

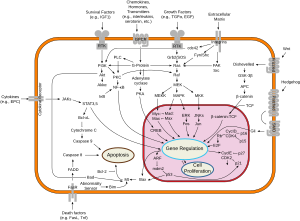

Cellular differentiation is often controlled by cell signaling. Many of the signal molecules that convey information from cell to cell during the control of cellular differentiation are called growth factors. Although the details of specific signal transduction pathways vary, these pathways often share the following general steps. A ligand produced by one cell binds to a receptor in the extracellular region of another cell, inducing a conformational change in the receptor. The shape of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor changes, and the receptor acquires enzymatic activity. The receptor then catalyzes reactions that phosphorylate other proteins, activating them. A cascade of phosphorylation reactions eventually activates a dormant transcription factor or cytoskeletal protein, thus contributing to the differentiation process in the target cell. Cells and tissues can vary in competence, their ability to respond to external signals.

Signal induction refers to cascades of signaling events, during which a cell or tissue signals to another cell or tissue to influence its developmental fate. Yamamoto and Jeffery investigated the role of the lens in eye formation in cave- and surface-dwelling fish, a striking example of induction. Through reciprocal transplants, Yamamoto and Jeffery found that the lens vesicle of surface fish can induce other parts of the eye to develop in cave- and surface-dwelling fish, while the lens vesicle of the cave-dwelling fish cannot.

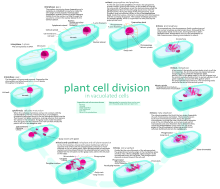

Other important mechanisms fall under the category of asymmetric cell divisions, divisions that give rise to daughter cells with distinct developmental fates. Asymmetric cell divisions can occur because of asymmetrically expressed maternal cytoplasmic determinants or because of signaling. In the former mechanism, distinct daughter cells are created during cytokinesis because of an uneven distribution of regulatory molecules in the parent cell; the distinct cytoplasm that each daughter cell inherits results in a distinct pattern of differentiation for each daughter cell. A well-studied example of pattern formation by asymmetric divisions is body axis patterning in Drosophila. RNA molecules are an important type of intracellular differentiation control signal. The molecular and genetic basis of asymmetric cell divisions has also been studied in green algae of the genus Volvox, a model system for studying how unicellular organisms can evolve into multicellular organisms. In Volvox carteri, the 16 cells in the anterior hemisphere of a 32-cell embryo divide asymmetrically, each producing one large and one small daughter cell. The size of the cell at the end of all cell divisions determines whether it becomes a specialized germ or somatic cell.

Epigenetic control

Since each cell, regardless of cell type, possesses the same genome, determination of cell type must occur at the level of gene expression. While the regulation of gene expression can occur through cis- and trans-regulatory elements including a gene's promoter and enhancers, the problem arises as to how this expression pattern is maintained over numerous generations of cell division. As it turns out, epigenetic processes play a crucial role in regulating the decision to adopt a stem, progenitor, or mature cell fate. This section will focus primarily on mammalian stem cells.

In systems biology and mathematical modeling of gene regulatory networks, cell-fate determination is predicted to exhibit certain dynamics, such as attractor-convergence (the attractor can be an equilibrium point, limit cycle or strange attractor) or oscillatory.

Importance of epigenetic control

The first question that can be asked is the extent and complexity of the role of epigenetic processes in the determination of cell fate. A clear answer to this question can be seen in the 2011 paper by Lister R, et al. on aberrant epigenomic programming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. As induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are thought to mimic embryonic stem cells in their pluripotent properties, few epigenetic differences should exist between them. To test this prediction, the authors conducted whole-genome profiling of DNA methylation patterns in several human embryonic stem cell (ESC), iPSC, and progenitor cell lines.

Female adipose cells, lung fibroblasts, and foreskin fibroblasts were reprogrammed into induced pluripotent state with the OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC genes. Patterns of DNA methylation in ESCs, iPSCs, somatic cells were compared. Lister R, et al. observed significant resemblance in methylation levels between embryonic and induced pluripotent cells. Around 80% of CG dinucleotides in ESCs and iPSCs were methylated, the same was true of only 60% of CG dinucleotides in somatic cells. In addition, somatic cells possessed minimal levels of cytosine methylation in non-CG dinucleotides, while induced pluripotent cells possessed similar levels of methylation as embryonic stem cells, between 0.5 and 1.5%. Thus, consistent with their respective transcriptional activities, DNA methylation patterns, at least on the genomic level, are similar between ESCs and iPSCs.

However, upon examining methylation patterns more closely, the authors discovered 1175 regions of differential CG dinucleotide methylation between at least one ES or iPS cell line. By comparing these regions of differential methylation with regions of cytosine methylation in the original somatic cells, 44-49% of differentially methylated regions reflected methylation patterns of the respective progenitor somatic cells, while 51-56% of these regions were dissimilar to both the progenitor and embryonic cell lines. In vitro-induced differentiation of iPSC lines saw transmission of 88% and 46% of hyper and hypo-methylated differentially methylated regions, respectively.

Two conclusions are readily apparent from this study. First, epigenetic processes are heavily involved in cell fate determination, as seen from the similar levels of cytosine methylation between induced pluripotent and embryonic stem cells, consistent with their respective patterns of transcription. Second, the mechanisms of reprogramming (and by extension, differentiation) are very complex and cannot be easily duplicated, as seen by the significant number of differentially methylated regions between ES and iPS cell lines. Now that these two points have been established, we can examine some of the epigenetic mechanisms that are thought to regulate cellular differentiation.

Mechanisms of epigenetic regulation

Pioneer factors (Oct4, Sox2, Nanog)

Three transcription factors, OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG – the first two of which are used in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming, along with Klf4 and c-Myc – are highly expressed in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells and are necessary for the maintenance of their pluripotency. It is thought that they achieve this through alterations in chromatin structure, such as histone modification and DNA methylation, to restrict or permit the transcription of target genes. While highly expressed, their levels require a precise balance to maintain pluripotency, perturbation of which will promote differentiation towards different lineages based on how the gene expression levels change. Differential regulation of Oct-4 and SOX2 levels have been shown to precede germ layer fate selection. Increased levels of Oct4 and decreased levels of Sox2 promote a mesendodermal fate, with Oct4 actively suppressing genes associated with a neural ectodermal fate. Similarly, Increased levels of Sox2 and decreased levels of Oct4 promote differentiation towards a neural ectodermal fate, with Sox2 inhibiting differentiation towards a mesendodermal fate. Regardless of the lineage cells differentiate down, suppression of NANOG has been identified as a necessary prerequisite for differentiation.

Polycomb repressive complex (PRC2)

In the realm of gene silencing, Polycomb repressive complex 2, one of two classes of the Polycomb group (PcG) family of proteins, catalyzes the di- and tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me2/me3). By binding to the H3K27me2/3-tagged nucleosome, PRC1 (also a complex of PcG family proteins) catalyzes the mono-ubiquitinylation of histone H2A at lysine 119 (H2AK119Ub1), blocking RNA polymerase II activity and resulting in transcriptional suppression. PcG knockout ES cells do not differentiate efficiently into the three germ layers, and deletion of the PRC1 and PRC2 genes leads to increased expression of lineage-affiliated genes and unscheduled differentiation. Presumably, PcG complexes are responsible for transcriptionally repressing differentiation and development-promoting genes.

Trithorax group proteins (TrxG)

Alternately, upon receiving differentiation signals, PcG proteins are recruited to promoters of pluripotency transcription factors. PcG-deficient ES cells can begin differentiation but cannot maintain the differentiated phenotype. Simultaneously, differentiation and development-promoting genes are activated by Trithorax group (TrxG) chromatin regulators and lose their repression. TrxG proteins are recruited at regions of high transcriptional activity, where they catalyze the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and promote gene activation through histone acetylation. PcG and TrxG complexes engage in direct competition and are thought to be functionally antagonistic, creating at differentiation and development-promoting loci what is termed a "bivalent domain" and rendering these genes sensitive to rapid induction or repression.

DNA methylation

Regulation of gene expression is further achieved through DNA methylation, in which the DNA methyltransferase-mediated methylation of cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides maintains heritable repression by controlling DNA accessibility. The majority of CpG sites in embryonic stem cells are unmethylated and appear to be associated with H3K4me3-carrying nucleosomes. Upon differentiation, a small number of genes, including OCT4 and NANOG, are methylated and their promoters repressed to prevent their further expression. Consistently, DNA methylation-deficient embryonic stem cells rapidly enter apoptosis upon in vitro differentiation.

Nucleosome positioning

While the DNA sequence of most cells of an organism is the same, the binding patterns of transcription factors and the corresponding gene expression patterns are different. To a large extent, differences in transcription factor binding are determined by the chromatin accessibility of their binding sites through histone modification and/or pioneer factors. In particular, it is important to know whether a nucleosome is covering a given genomic binding site or not. This can be determined using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay.

Histone acetylation and methylation

DNA-nucleosome interactions are characterized by two states: either tightly bound by nucleosomes and transcriptionally inactive, called heterochromatin, or loosely bound and usually, but not always, transcriptionally active, called euchromatin. The epigenetic processes of histone methylation and acetylation, and their inverses demethylation and deacetylation primarily account for these changes. The effects of acetylation and deacetylation are more predictable. An acetyl group is either added to or removed from the positively charged Lysine residues in histones by enzymes called histone acetyltransferases or histone deacteylases, respectively. The acetyl group prevents Lysine's association with the negatively charged DNA backbone. Methylation is not as straightforward, as neither methylation nor demethylation consistently correlate with either gene activation or repression. However, certain methylations have been repeatedly shown to either activate or repress genes. The trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone 3 (H3K4Me3) is associated with gene activation, whereas trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone 3 represses genes.

In stem cells

During differentiation, stem cells change their gene expression profiles. Recent studies have implicated a role for nucleosome positioning and histone modifications during this process. There are two components of this process: turning off the expression of embryonic stem cell (ESC) genes, and the activation of cell fate genes. Lysine specific demethylase 1 (KDM1A) is thought to prevent the use of enhancer regions of pluripotency genes, thereby inhibiting their transcription. It interacts with Mi-2/NuRD complex (nucleosome remodelling and histone deacetylase) complex, giving an instance where methylation and acetylation are not discrete and mutually exclusive, but intertwined processes.

Role of signaling in epigenetic control

A final question to ask concerns the role of cell signaling in influencing the epigenetic processes governing differentiation. Such a role should exist, as it would be reasonable to think that extrinsic signaling can lead to epigenetic remodeling, just as it can lead to changes in gene expression through the activation or repression of different transcription factors. Little direct data is available concerning the specific signals that influence the epigenome, and the majority of current knowledge about the subject consists of speculations on plausible candidate regulators of epigenetic remodeling. We will first discuss several major candidates thought to be involved in the induction and maintenance of both embryonic stem cells and their differentiated progeny, and then turn to one example of specific signaling pathways in which more direct evidence exists for its role in epigenetic change.

The first major candidate is Wnt signaling pathway. The Wnt pathway is involved in all stages of differentiation, and the ligand Wnt3a can substitute for the overexpression of c-Myc in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. On the other hand, disruption of β-catenin, a component of the Wnt signaling pathway, leads to decreased proliferation of neural progenitors.

Growth factors comprise the second major set of candidates of epigenetic regulators of cellular differentiation. These morphogens are crucial for development, and include bone morphogenetic proteins, transforming growth factors (TGFs), and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs). TGFs and FGFs have been shown to sustain expression of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG by downstream signaling to Smad proteins. Depletion of growth factors promotes the differentiation of ESCs, while genes with bivalent chromatin can become either more restrictive or permissive in their transcription.

Several other signaling pathways are also considered to be primary candidates. Cytokine leukemia inhibitory factors are associated with the maintenance of mouse ESCs in an undifferentiated state. This is achieved through its activation of the Jak-STAT3 pathway, which has been shown to be necessary and sufficient towards maintaining mouse ESC pluripotency. Retinoic acid can induce differentiation of human and mouse ESCs, and Notch signaling is involved in the proliferation and self-renewal of stem cells. Finally, Sonic hedgehog, in addition to its role as a morphogen, promotes embryonic stem cell differentiation and the self-renewal of somatic stem cells.

The problem, of course, is that the candidacy of these signaling pathways was inferred primarily on the basis of their role in development and cellular differentiation. While epigenetic regulation is necessary for driving cellular differentiation, they are certainly not sufficient for this process. Direct modulation of gene expression through modification of transcription factors plays a key role that must be distinguished from heritable epigenetic changes that can persist even in the absence of the original environmental signals. Only a few examples of signaling pathways leading to epigenetic changes that alter cell fate currently exist, and we will focus on one of them.

Expression of Shh (Sonic hedgehog) upregulates the production of BMI1, a component of the PcG complex that recognizes H3K27me3. This occurs in a Gli-dependent manner, as Gli1 and Gli2 are downstream effectors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. In culture, Bmi1 mediates the Hedgehog pathway's ability to promote human mammary stem cell self-renewal. In both humans and mice, researchers showed Bmi1 to be highly expressed in proliferating immature cerebellar granule cell precursors. When Bmi1 was knocked out in mice, impaired cerebellar development resulted, leading to significant reductions in postnatal brain mass along with abnormalities in motor control and behavior.[42] A separate study showed a significant decrease in neural stem cell proliferation along with increased astrocyte proliferation in Bmi null mice.

An alternative model of cellular differentiation during embryogenesis is that positional information is based on mechanical signalling by the cytoskeleton using Embryonic differentiation waves. The mechanical signal is then epigenetically transduced via signal transduction systems (of which specific molecules such as Wnt are part) to result in differential gene expression.

In summary, the role of signaling in the epigenetic control of cell fate in mammals is largely unknown, but distinct examples exist that indicate the likely existence of further such mechanisms.

Effect of matrix elasticity

In order to fulfill the purpose of regenerating a variety of tissues, adult stems are known to migrate from their niches, adhere to new extracellular matrices (ECM) and differentiate. The ductility of these microenvironments are unique to different tissue types. The ECM surrounding brain, muscle and bone tissues range from soft to stiff. The transduction of the stem cells into these cells types is not directed solely by chemokine cues and cell to cell signaling. The elasticity of the microenvironment can also affect the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs which originate in bone marrow.) When MSCs are placed on substrates of the same stiffness as brain, muscle and bone ECM, the MSCs take on properties of those respective cell types. Matrix sensing requires the cell to pull against the matrix at focal adhesions, which triggers a cellular mechano-transducer to generate a signal to be informed what force is needed to deform the matrix. To determine the key players in matrix-elasticity-driven lineage specification in MSCs, different matrix microenvironments were mimicked. From these experiments, it was concluded that focal adhesions of the MSCs were the cellular mechano-transducer sensing the differences of the matrix elasticity. The non-muscle myosin IIa-c isoforms generates the forces in the cell that lead to signaling of early commitment markers. Nonmuscle myosin IIa generates the least force increasing to non-muscle myosin IIc. There are also factors in the cell that inhibit non-muscle myosin II, such as blebbistatin. This makes the cell effectively blind to the surrounding matrix. Researchers have obtained some success in inducing stem cell-like properties in HEK 239 cells by providing a soft matrix without the use of diffusing factors. The stem-cell properties appear to be linked to tension in the cells' actin network. One identified mechanism for matrix-induced differentiation is tension-induced proteins, which remodel chromatin in response to mechanical stretch. The RhoA pathway is also implicated in this process.

Evolutionary history

A billion-years-old, likely holozoan, protist, Bicellum brasieri with two types of cells, shows that the evolution of differentiated multicellularity, possibly but not necessarily of animal lineages, occurred at least 1 billion years ago and possibly mainly in freshwater lakes rather than the ocean.