From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Medieval port crane for mounting masts and lifting heavy cargo in the former

Hanse town of

GdańskMedieval technology is the technology used in medieval Europe under Christian rule. After the Renaissance of the 12th century,

medieval Europe saw a radical change in the rate of new inventions,

innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and

economic growth. The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder, the invention of vertical windmills, spectacles, mechanical clocks, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques (Gothic architecture, medieval castles), and agriculture in general (three-field crop rotation).

The development of water mills from their ancient origins was impressive, and extended from agriculture to sawmills both for timber and stone. By the time of the Domesday Book, most large villages had turnable mills, around 6,500 in England alone. Water-power was also widely used in mining for raising ore from shafts, crushing ore, and even powering bellows.

Many European technical advancements from the 12th to 14th

centuries were either built on long-established techniques in medieval

Europe, originating from Roman and Byzantine antecedents, or adapted from cross-cultural exchanges through trading networks with the Islamic world, China, and India.

Often, the revolutionary aspect lay not in the act of invention itself,

but in its technological refinement and application to political and

economic power. Though gunpowder

along with other weapons had been started by Chinese, it was the

Europeans who developed and perfected its military potential,

precipitating European expansion and eventual imperialism in the Modern

Era.

Also significant in this respect were advances in maritime technology. Advances in shipbuilding included the multi-masted ships with lateen sails, the sternpost-mounted rudder and the skeleton-first hull construction. Along with new navigational techniques such as the dry compass, the Jacob's staff and the astrolabe,

these allowed economic and military control of the seas adjacent to

Europe and enabled the global navigational achievements of the dawning Age of Exploration.

At the turn to the Renaissance, Gutenberg's invention of mechanical printing

made possible a dissemination of knowledge to a wider population, that

would not only lead to a gradually more egalitarian society, but one

more able to dominate other cultures, drawing from a vast reserve of

knowledge and experience. The technical drawings of late-medieval

artist-engineers Guido da Vigevano and Villard de Honnecourt can be viewed as forerunners of later Renaissance artist-engineers such as Taccola or Leonardo da Vinci.

Civil technologies

The

following is a list of some important medieval technologies. The

approximate date or first mention of a technology in medieval Europe is

given. Technologies were often a matter of cultural exchange and date

and place of first inventions are not listed here (see main links for a

more complete history of each).

Agriculture

Carruca (6th to 9th centuries)

A type of heavy wheeled plough commonly found in Northern Europe. The device consisted of four major parts. The first part was a coulter at the bottom of the plough. This knife was used to vertically cut into the top sod to allow for the plowshare to work. The plowshare was the second pair of knives which cut the sod horizontally, detaching it from the ground below. The third part was the moldboard, which curled the sod outward. The fourth part of the device was the team of eight oxen guided by the farmer. This type of plough eliminated the need for cross-plowing by turning over the furrow instead of merely pushing it outward.

This type of wheeled plough made seed placement more consistent

throughout the farm as the blade could be locked in at a certain level

relative to the wheels. A disadvantage to this type of plough was its

poor maneuverability. Since this equipment was large and led by a small

herd of oxen, turning the plough was difficult and time-consuming. This

caused many farmers to turn away from traditional square fields and

adopt a longer, more rectangular field to ensure maximum efficiency.

Ard (plough) (5th century)

Medieval plough and oxen team

While ploughs have been used since ancient times, during the medieval period plough technology improved rapidly.

The medieval plough, constructed from wooden beams, could be yoked to

either humans or a team of oxen and pulled through any type of terrain.

This allowed for faster clearing of forest lands for agriculture in

parts of Northern Europe where the soil contained rocks and dense tree

roots. With more food being produced, more people were able to live in these areas.

Horse collar (6th to 9th centuries)

Once oxen started to be replaced by horses on farms and in fields, the yoke became obsolete due to its shape not working well with a horses' posture. The first design for a horse collar was a throat-and-girth-harness. These types of harnesses were unreliable though due to them not being sufficiently set in place. The loose straps were prone to slipping and shifting positions as the horse was working and often caused asphyxiation. Around the eighth century, the introduction of the rigid collar eliminated the problem of choking. The rigid collar was "placed over the horses head and rested on its shoulders. This permitted unobstructed breathing and placed the weight of the plow or wagon where the horse could best support it."

Horseshoes (9th century)

While horses are already able to travel on all terrain without a

protective covering on the hooves, horseshoes allowed horses to travel

faster along the more difficult terrains.

The practice of shoeing horses was initially practiced in the Roman

Empire but lost popularity throughout the Middle Ages until around the

11th century.

Although horses in the southern lands could easily work while on the

softer soil, the rocky soil of the north proved to be damaging to the

horses' hooves. Since the north was the problematic area, this is where shoeing horses first became popular. The introduction of gravel roadways was also cause for the popularity of horseshoeing. The loads a shoed horse could take on these roads were significantly higher than one that was barefoot.

By the 14th century, not only did horses have shoes, but many farmers

were shoeing oxen and donkeys in order to help prolong the life of their

hooves. The size and weight of the horseshoe changed significantly over the course of the Middle Ages.

In the 10th century, horseshoes were secured by six nails and weighed

around one-quarter of a pound, but throughout the years, the shoes grew

larger and by the 14th century, the shoes were being secured with eight

nails and weighed nearly half a pound.

Crop rotation

Two-field system

In this simpler form of crop rotation, one field would grow a

crop while the other was allowed to lie fallow. The second field would

be used to feed livestock and regain lost nutrients through being

fertilized by their waste. Every year, the two fields would switch in order to ensure fields did not become nutrient deficient. In the 11th century, this system was introduced into Sweden and spread to become the most popular form of farming.

The system of crop rotation is still used today by many farmers, who

will grow corn one year in a field and will then grow beans or other

legumes in the field the next year.

Three-field system (8th century)

While the two-field system was used by medieval farmers, a

different system was also being developed at the same time. In a

three-field system, one field holds a spring crop, such as barley or

oats, another field holds a winter crop, such as wheat or rye, and the

third field is an off-field that is left alone to grow and is used to

help feed livestock.

By rotating the three crops to a new part of the land after each year,

the off-field regains some of the nutrients lost during the growing of

the two crops.

This system increases agricultural productivity over the two-field

system by only having one-third of the land unused instead of one half. Many scholars believe it helped increase yields by up to 50%.

Wine press (12th century)

A wine press used in the medieval period to crush grapes.

During the medieval period the wine press had been constantly

evolving into a more modern and efficient machine that would give wine

makers more wine with less work. This device was the first practical means of pressing wine on a flat surface.

The wine press was made of a giant wooden basket that was bound

together by wooden or metal rings. At the top of the basket was a large

disc that would depress the contents in the basket, crushing the grapes

and producing the juice to be fermented.

The wine press was an expensive piece of machinery that only the wealthy could afford, and grape stomping was still often used as a less expensive alternative.

While white wines required the use of a wine press in order to preserve

the color of the wine by removing the juices quickly from the skin, red

wine did not need to be pressed until the end of the juice removal

process since the color did not matter.

Many red wine winemakers used their feet to smash the grapes then used a

press to remove any juice that remained in the grape skins.

Qanat (water ducts) (5th century)

A medieval aqueduct unearthed

Ancient and medieval civilizations needed and used water to grow the

human population as well as to partake in daily activities. One of the

ways that ancient and medieval people gained access to water was through

qanats, which were a water duct system that would bring water from an

underground source or river source to villages or cities.

A qanat is a tunnel that is just big enough that a single digger could

travel through the tunnel and find the source of water as well as allow

for water to travel through the duct system to farm land or villages for

irrigation or drinking purposes. These tunnels had a gradual slope

which used gravity to pull the water from either an aquifer or a water well. This system was originally found in middle eastern areas and is still used today in places where surface water is hard to find.

Qanats were very helpful in not losing water while being transported as

well. The most famous water duct system was the Roman aqueduct system,

and medieval inventors used the aqueduct system as a blueprint for

getting water to villages more quickly and easily than diverting rivers.

After aqueducts and qanats much other water based technology was

created and used in medieval periods including water mills, dams, wells

and other such technology for easy access to water.

Architecture and construction

Pendentive architecture (6th century)

A specific spherical form in the upper corners to support a dome.

Although the first experimentation was made in the 3rd century, it

wasn't until the 6th century in the Byzantine Empire that its full potential was achieved.

Artesian well (1126)

A thin rod with a hard iron cutting edge is placed in the bore

hole and repeatedly struck with a hammer, underground water pressure

forces the water up the hole without pumping. Artesian wells are named

after the town of Artois in France, where the first one was drilled by

Carthusian monks in 1126.

Central heating through underfloor channels (9th century)

In the early medieval Alpine upland, a simpler central heating

system where heat travelled through underfloor channels from the furnace

room replaced the Roman hypocaust at some places. In Reichenau Abbey a network of interconnected underfloor channels heated the 300 m2 large assembly room of the monks during the winter months. The degree of efficiency of the system has been calculated at 90%.

Rib vault (12th century)

An essential element for the rise of Gothic architecture,

rib vaults allowed vaults to be built for the first time over

rectangles of unequal lengths. It also greatly facilitated scaffolding

and largely replaced the older groin vault.

Chimney (12th century)

The first basic chimney appeared in a Swiss monastery in 820. The

earliest true chimney did not appear until the 12th century, with the

fireplace appearing at the same time.

Segmental arch bridge (1345)

The Ponte Vecchio in Florence is considered medieval Europe's first stone segmental arch bridge since the end of classical civilizations.

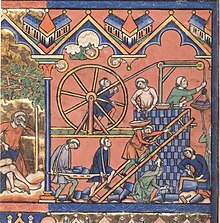

Treadwheel crane (1220s)

The earliest reference to a treadwheel in archival literature is in France about 1225, followed by an illuminated depiction in a manuscript of probably also French origin dating to 1240. Apart from tread-drums, windlasses and occasionally cranks were employed for powering cranes.

Stationary harbour crane (1244)

Stationary harbour cranes are considered a new development of the

Middle Ages; its earliest use being documented for Utrecht in 1244.

The typical harbour crane was a pivoting structure equipped with double

treadwheels. There were two types: wooden gantry cranes pivoting on a

central vertical axle and stone tower cranes which housed the windlass

and treadwheels with only the jib arm and roof rotating.

These cranes were placed on docksides for the loading and unloading of

cargo where they replaced or complemented older lifting methods like see-saws, winches and yards. Slewing cranes which allowed a rotation of the load and were thus particularly suited for dockside work appeared as early as 1340.

Floating crane

Beside the stationary cranes, floating cranes which could be flexibly

deployed in the whole port basin came into use by the 14th century.

Mast crane

Some harbour cranes were specialised at mounting masts to newly built sailing ships, such as in Gdańsk, Cologne and Bremen.

Wheelbarrow (1170s)

The wheelbarrow proved useful in building construction, mining

operations, and agriculture. Literary evidence for the use of

wheelbarrows appeared between 1170 and 1250 in north-western Europe. The

first depiction is in a drawing by Matthew Paris in the mid-13th century.

Art

Oil paint (by 1125)

As early as the 13th century, oil was used to add details to tempera paintings and paint wooden statues. Flemish painter Jan van Eyck developed the use of a stable oil mixture for panel painting around 1410.

Clocks

Hourglass (1338)

Reasonably dependable, affordable and accurate measure of time. Unlike water in a clepsydra,

the rate of flow of sand is independent of the depth in the upper

reservoir, and the instrument is not liable to freeze. Hourglasses are a

medieval innovation (first documented in Siena, Italy).

Mechanical clocks (13th to 14th centuries)

A European innovation, these weight-driven clocks were used primarily in clock towers.

Mechanics

Compound crank

The Italian physician Guido da Vigevano combines in his 1335 Texaurus,

a collection of war machines intended for the recapture of the Holy

Land, two simple cranks to form a compound crank for manually powering

war carriages and paddle wheel boats. The devices were fitted directly to the vehicle's axle respectively to the shafts turning the paddle wheels.

Metallurgy

Blast furnace (1150–1350)

Cast iron had been made in China since before the 4th century BC.

European cast iron first appears in Middle Europe (for instance

Lapphyttan in Sweden, Dürstel in Switzerland and the Märkische Sauerland

in Germany) around 1150, in some places according to recent research even before 1100. The technique is considered to be an independent European development.

Milling

An example of a ship mill.

Ship mill (6th century)

The ship mill is a Byzantine invention, designed to mill grains

using hydraulic power. The technology eventually spread to the rest of

Europe and was in use until ca. 1800.

Paper mill (13th century)

The first certain use of a water-powered paper mill, evidence for which is elusive in both Chinese and Muslim paper making, dates to 1282.

Rolling mill (15th century)

Used to produce metal sheet of an even thickness. First used on soft, malleable metals, such as lead, gold and tin. Leonardo da Vinci described a rolling mill for wrought iron.

Tidal mills (6th century)

The earliest tidal mills were excavated on the Irish coast where watermillers knew and employed the two main waterwheel types: a 6th-century tide mill at Killoteran near Waterford was powered by a vertical waterwheel, while the tide changes at Little Island were exploited by a twin-flume horizontal-wheeled mill (c. 630) and a vertical undershot waterwheel alongside it. Another early example is the Nendrum Monastery mill from 787 which is estimated to have developed seven to eight horsepower at its peak.

An example of a water hammer

Vertical windmills (1180s)

Invented in Europe as the pivotable post mill, the first

surviving mention of one comes from Yorkshire in England in 1185. They

were efficient at grinding grain or draining water. Stationary tower

mills were also developed in the 13th century.

Water hammer (12th century at the latest)

Used in metallurgy to forge the metal blooms from bloomeries and Catalan forges, they replaced manual hammerwork. The water hammer was eventually superseded by steam hammers in the 19th century.

Navigation

Dry compass (12th century)

The first European mention of the directional compass is in Alexander Neckam's On the Natures of Things, written in Paris around 1190. It was either transmitted from China or the Arabs or an independent European innovation. Dry compass were invented in the Mediterranean around 1300.

Astronomical compass (1269)

The French scholar Pierre de Maricourt describes in his experimental study Epistola de magnete (1269) three different compass designs he has devised for the purpose of astronomical observation.

Scheme of a sternpost-mounted medieval rudder

Stern-mounted rudders (1180s)

The first depiction of a pintle-and-gudgeon rudder on church carvings dates to around 1180. They first appeared with cogs

in the North and Baltic Seas and quickly spread to Mediterranean. The

iron hinge system was the first stern rudder permanently attached to the

ship hull and made a vital contribution to the navigation achievements

of the age of discovery and thereafter.

Printing, paper and reading

Movable type printing press (1440s)

Johannes Gutenberg's great innovation was not the printing itself, but instead of using carved plates as in woodblock printing, he used separate letters (types)

from which the printing plates for pages were made up. This meant the

types were recyclable and a page cast could be made up far faster.

Paper (13th century)

Paper was invented in China and transmitted through Islamic Spain

in the 13th century. In Europe, the paper-making processes was

mechanized by water-powered mills and paper presses (see paper mill).

Rotating bookmark (13th century)

A rotating disc and string device used to mark the page, column,

and precise level in the text where a person left off reading in a text.

Materials used were often leather, velum, or paper.

Spectacles (1280s)

The first spectacles, invented in Florence, used convex lenses

which were of help only to the far-sighted. Concave lenses were not

developed prior to the 15th century.

Watermark (1282)

This medieval innovation was used to mark paper products and to discourage counterfeiting. It was first introduced in Bologna, Italy.

Science and learning

Theory of impetus (6th century)

A scientific theory that was introduced by John Philoponus who made criticism of Aristotelian principles of physics, and it served as an inspiration to medieval scholars as well as to Galileo Galilei who ten centuries later, during the Scientific Revolution,

extensively cited Philoponus in his works while making the case as to

why Aristotelian physics was flawed. It is the intellectual precursor to

the concepts of inertia, momentum and acceleration in classical mechanics.

The first extant treatise of magnetism (13th century)

The first extant treatise describing the properties of magnets was done by Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt when he wrote Epistola de magnete.

Arabic numerals (13th century)

The first recorded mention in Europe was in 976, and they were first widely published in 1202 by Fibonacci with his Liber Abaci.

University

The first medieval universities

were founded between the 11th and 13th centuries leading to a rise in

literacy and learning. By 1500, the institution had spread throughout

most of Europe and played a key role in the Scientific Revolution. Today, the educational concept and institution has been globally adopted.

Textile industry and garments

Functional button (13th century)

German buttons appeared in 13th-century Germany as an indigenous innovation. They soon became widespread with the rise of snug-fitting clothing.

Horizontal loom (11th century)

Horizontal looms operated by foot-treadles were faster and more efficient.

Silk (6th century)

Manufacture of silk began in Eastern Europe in the 6th century

and in Western Europe in the 11th or 12th century. Silk had been

imported over the Silk Road

since antiquity. The technology of "silk throwing" was mastered in

Tuscany in the 13th century. The silk works used waterpower and some

regard these as the first mechanized textile mills.

Spinning wheel (13th century)

Brought to Europe probably from India.

Miscellaneous

Chess (1450)

The earliest predecessors of the game originated in 6th-century

AD India and spread via Persia and the Muslim world to Europe. Here the

game evolved into its current form in the 15th century.

Forest glass (c. 1000)

This type of glass uses wood ash and sand as the main raw materials and is characterised by a variety of greenish-yellow colours.

Grindstones (834)

Grindstones are a rough stone, usually sandstone, used to sharpen

iron. The first rotary grindstone (turned with a leveraged handle)

occurs in the Utrecht Psalter, illustrated between 816 and 834. According to Hägermann, the pen drawing is a copy of a late-antique manuscript. A second crank which was mounted on the other end of the axle is depicted in the Luttrell Psalter from around 1340.

Liquor (12th century)

Primitive forms of distillation were known to the Babylonians, as well as Indians in the first centuries AD. Early evidence of distillation also comes from alchemists working in Alexandria, Roman Egypt, in the 1st century. The medieval Arabs adopted the distillation process, which later spread to Europe. Texts on the distillation of waters, wine, and other spirits were written in Salerno and Cologne in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Liquor consumption rose dramatically in Europe in and after the

mid-14th century, when distilled liquors were commonly used as remedies

for the Black Death. These spirits would have had a much lower alcohol content (about 40% ABV) than the alchemists' pure distillations, and they were likely first thought of as medicinal elixirs. Around 1400, methods to distill spirits from wheat, barley, and rye were discovered. Thus began the "national" drinks of Europe, including gin (England) and grappa (Italy). In 1437, "burned water" (brandy) was mentioned in the records of the County of Katzenelnbogen in Germany.

Magnets (12th century)

Magnets were first referenced in the Roman d'Enéas, composed between 1155 and 1160.

Mirrors (1180)

The first mention of a "glass" mirror is in 1180 by Alexander Neckham who said "Take away the lead which is behind the glass and there will be no image of the one looking in."

Illustrated surgical atlas (1345)

Guido da Vigevano (c. 1280 − 1349) was the first author to add illustrations to his anatomical descriptions. His Anathomia provides pictures of neuroanatomical structures and techniques such as the dissection of the head by means of trephination, and depictions of the meninges, cerebrum, and spinal cord.

Quarantine (1377)

Initially a 40-day-period, the quarantine was introduced by the Republic of Ragusa as a measure of disease prevention related to the Black Death. It was later adopted by Venice from where the practice spread all around in Europe.

Rat traps (1170s)

The first mention of a rat trap is in the medieval romance Yvain, the Knight of the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes.

Military technologies

Armour

Quilted armour (pre-5th–14th Century)

There was a vast amount of armour technology available through

the 5th to 16th centuries. Most soldiers during this time wore padded or

quilted armor. This was the cheapest and most available armor for the

majority of soldiers. Quilted armour was usually just a jacket made of

thick linen and wool meant to pad or soften the impact of blunt weapons

and light blows. Although this technology predated the 5th century, it

was still extremely prevalent because of the low cost and the weapon

technology at the time made the bronze armor of the Greeks and Romans

obsolete. Quilted armour was also used in conjunction with other types

of armour. Usually worn over or under leather, mail, and later plate

armour.

Cuir Bouilli (5th–10th Century)

Hardened leather armour also called Cuir Bouilli was a step up

from quilted armour. Made by boiling leather in either water, wax or oil

to soften it so it can be shaped, it would then be allowed to dry and

become very hard.

Large pieces of armour could be made such as breastplates, helmets, and

leg guards, but many times smaller pieces would be sewn into the

quilting of quilted armour or strips would be sewn together on the

outside of a linen jacket. This was not as affordable as the quilted

armour but offered much better protection against edged slashing

weapons.

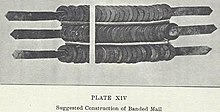

Banded Mail Armour Construction

Chain mail (11th–16th Century)

The most common type during the 11th through the 16th centuries was the Hauberk, also known earlier than the 11th century as the Carolingian byrnie.

Made of interlinked rings of metal, it sometimes consisted of a coif

that covered the head and a tunic that covered the torso, arms, and legs

down to the knees. Chain mail was very effective at protecting against

light slashing blows but ineffective against stabbing or thrusting

blows. The great advantage was that it allowed great freedom of movement

and was relatively light with significant protection over quilted or

hardened leather armour. It was far more expensive than the hardened

leather or quilted armour because of the massive amount of labor it

required to create. This made it unattainable for most soldiers and only

the more wealthy soldiers could afford it. Later, toward the end of the

13th century banded mail became popular.

Constructed of washer shaped rings of iron overlapped and woven

together by straps of leather as opposed to the interlinked metal rings

of chain mail, banded mail was much more affordable to manufacture. The

washers were so tightly woven together that it was very difficult

penetrate and offered greater protection from arrow and bolt attacks.

Jazerant (11th century)

The Jazerant or Jazeraint was an adaptation of chain mail in

which the chain mail would be sewn in between layers of linen or quilted

armour.

Exceptional protection against light slashing weapons and slightly

improved protection against small thrusting weapons, but little

protection against large blunt weapons such as maces and axes. This gave

birth to reinforced chain mail and became more prevalent in the 12th

and 13th century. Reinforced armour was made up of chain mail with metal

plates or hardened leather plates sewn in. This greatly improved

protection from stabbing and thrusting blows.

Scale armour (12th century)

A type of Lamellar armour,

was made up entirely of small, overlapping plates. Either sewn

together, usually with leather straps, or attached to a backing such as

linen, or a quilted armor. Scale armour does not require the labor to

produce that chain mail does and therefore is more affordable. It also

affords much better protection against thrusting blows and pointed

weapons. Though, it is much heavier, more restrictive and impedes free

movement.

Plate armour (14th century)

Plate armour covered the entire body. Although parts of the body

were already covered in plate armour as early as 1250, such as the

Poleyns for covering the knees and Couters – plates that protected the

elbows, the first complete full suit without any textiles was seen around 1410–1430. Components of medieval armour

that made up a full suit consisted of a cuirass, a gorget, vambraces,

gauntlets, cuisses, greaves, and sabatons held together by internal

leather straps. Improved weaponry such as crossbows and the long bow had

greatly increased range and power. This made penetration of the chain

mail hauberk much easier and more common. By the mid-15th century most plate was worn alone and without the need of a hauberk.

Advances in metal working such as the blast furnace and new techniques

for carburizing made plate armour nearly impenetrable and the best

armour protection available at the time. Although plate armour was

fairly heavy, because each suit was custom tailored to the wearer, it

was very easy to move around in. A full suit of plate armour was

extremely expensive and mostly unattainable for the majority of

soldiers. Only very wealthy land owners and nobility could afford it.

The quality of plate armour increases as more armour makers became more

proficient in metal working. A suit of plate armour became a symbol of

social status and the best made were personalized with embellishments

and engravings. Plate armour saw continued use in battle until the 17th

century.

Cavalry

Arched saddle (11th century)

The arched saddle enabled mounted knights to wield lances underarm and prevent the charge from turning into an unintentional pole-vault. This innovation gave birth to true shock cavalry, enabling fighters to charge on full gallop.

Spurs (11th century)

Spurs were invented by the Normans and appeared at the same time

as the cantled saddle. They enabled the horseman to control his horse

with his feet, replacing the whip and leaving his arms free. Rowel spurs

familiar from cowboy films were already known in the 13th century.

Gilded spurs were the ultimate symbol of the knighthood – even today

someone is said to "earn his spurs" by proving his or her worthiness.

Stirrup (6th century)

Stirrups were invented by steppe nomads in what is today Mongolia

and northern China in the 4th century. They were introduced in

Byzantium in the 6th century and in the Carolingian Empire in the 8th.

They allowed a mounted knight to wield a sword and strike from a

distance leading to a great advantage for mounted cavalry.

Gunpowder weapons

Cannon (1324)

Cannons are first recorded in Europe at the siege of Metz in 1324. In 1350 Petrarch

wrote "these instruments which discharge balls of metal with most

tremendous noise and flashes of fire...were a few years ago very rare

and were viewed with greatest astonishment and admiration, but now they

are become as common and familiar as kinds of arms."

Volley gun

See Ribauldequin.

Corned gunpowder (late 14th century)

First practiced in Western Europe, corning the black powder

allowed for more powerful and faster ignition of cannons. It also

facilitated the storage and transportation of black powder. Corning

constituted a crucial step in the evolution of gunpowder warfare.

Very large-calibre cannon (late 14th century)

Extant examples include the wrought-iron Pumhart von Steyr, Dulle Griet and Mons Meg as well as the cast-bronze Faule Mette and Faule Grete (all from the 15th century).

Mechanical artillery

Counterweight trebuchet (12th century)

Powered solely by the force of gravity, these catapults

revolutionized medieval siege warfare and construction of fortifications

by hurling huge stones unprecedented distances. Originating somewhere

in the eastern Mediterranean basin, counterweight trebuchets were

introduced in the Byzantine Empire around 1100 CE, and was later adopted by the Crusader states and as well by the other armies of Europe and Asia.

Missile weapons

Greek fire (7th century)

An incendiary weapon which could even burn on water is also

attributed to the Byzantines, where they installed it on their ships. It

played a crucial role in the Byzantine Empire's victory over the Umayyad Caliphate during the 717-718 Siege of Constantinople.

Grenade (8th century)

Rudimentary incendiary grenades appeared in the Byzantine Empire, as the Byzantine soldiers learned that Greek fire, a Byzantine invention of the previous century, could not only be thrown by flamethrowers at the enemy, but also in stone and ceramic jars.

Longbow with massed, disciplined archery (13th century)

Having a high rate of fire and penetration power, the longbow contributed to the eventual demise of the medieval knight class. Used particularly by the English to great effect against the French cavalry during the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453).

Steel crossbow (late 14th century)

European innovation came with several different cocking aids to

enhance draw power, making the weapons also the first hand-held

mechanical crossbows.

Miscellaneous

Combined arms tactics (14th century)

The battle of Halidon Hill 1333 was the first battle where intentional and disciplined combined arms infantry tactics were employed.

The English men-at-arms dismounted aside the archers, combining thus

the staying power of super-heavy infantry and striking power of their

two-handed weapons with the missiles and mobility of the archers using

longbows and shortbows. Combining dismounted knights and men-at-arms

with archers was the archetypal Western Medieval battle tactics until

the battle of Flodden 1513 and final emergence of firearms.