Sodomy laws in the United States, which outlawed a variety of sexual acts, were inherited from colonial laws in the 17th century. While they often targeted sexual acts between persons of the same sex, many statutes employed definitions broad enough to outlaw certain sexual acts between persons of different sexes, in some cases even including acts between married persons.

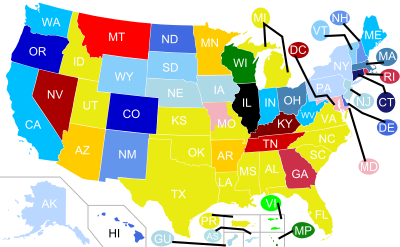

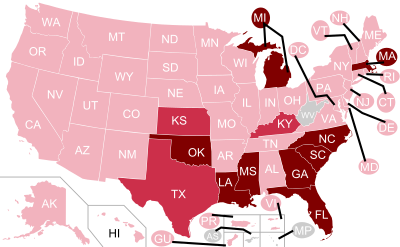

Through the 20th century, the gradual decriminalization of American sexuality led to the elimination of sodomy laws in most states. During this time, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of sodomy laws in Bowers v. Hardwick in 1986. However, in 2003, the Supreme Court reversed the decision with Lawrence v. Texas, invalidating sodomy laws in the remaining 14 states: Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah and Virginia.

History

Up to Lawrence v. Texas

Colin Talley argues that the sodomy statutes in colonial America in the 17th century were largely unenforced. The reason he argues is that male-male eroticism did not threaten the social structure or challenge the gendered division of labor or the patriarchal ownership of wealth. There were gay men on General Washington's staff and among the leaders of the new republic, even though in Virginia there was a maximum penalty of death for sodomy. In 1779, Thomas Jefferson tried to reduce the maximum punishment to castration. It was rejected by the Virginia legislature. Justice Anthony Kennedy authoring the majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas stated that American laws targeting same-sex couples did not develop until the last third of the 20th century and also wrote that:

Early American sodomy laws were not directed at homosexuals as such but instead sought to prohibit nonprocreative sexual activity more generally, whether between men and women or men and men. Moreover, early sodomy laws seem not to have been enforced against consenting adults acting in private. Instead, sodomy prosecutions often involved predatory acts against those who could not or did not consent: relations between men and minor girls or boys, between adults involving force, between adults implicating disparity in status, or between men and animals.

Prior to 1962, sodomy was a felony in every state, punished by a lengthy term of imprisonment and/or hard labor. In that year, the Model Penal Code (MPC) — developed by the American Law Institute to promote uniformity among the states as they modernized their statutes — struck a compromise that removed consensual sodomy from its criminal code while making it a crime to solicit for sodomy. In 1962, Illinois adopted the recommendations of the Model Penal Code and thus became the first state to remove criminal penalties for consensual sodomy from its criminal code, almost a decade before any other state. Over the years, many of the states that did not repeal their sodomy laws had enacted legislation reducing the penalty. At the time of the Lawrence decision in 2003, the penalty for violating a sodomy law varied very widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction among those states retaining their sodomy laws. The harshest penalties were in Idaho, where a person convicted of sodomy could earn a life sentence. Michigan followed, with a maximum penalty of 15 years' imprisonment while repeat offenders got life.

By 2002, 36 states had repealed their sodomy laws or their courts had overturned them. By the time of the 2003 Supreme Court decision, the laws in most states were no longer enforced or were enforced very selectively. The continued existence of these rarely enforced laws on the statute books, however, are often cited as justification for discrimination against gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals.

On June 26, 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court in a 6–3 decision in Lawrence v. Texas struck down the Texas same-sex sodomy law, ruling that this private sexual conduct is protected by the liberty rights implicit in the due process clause of the United States Constitution. This decision invalidated all state sodomy laws insofar as they applied to noncommercial conduct in private between consenting civilians and reversed the Court's 1986 ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick that upheld Georgia's sodomy law.

Before that 2003 ruling, 27 states, the District of Columbia, and 4 territories had repealed their sodomy laws by legislative action; 9 states had had them overturned or invalidated by state court action; 4 states still had same-sex sodomy laws; and 10 states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. military had anti-sodomy laws applying to all regardless of sex or gender.

Repeal since Lawrence v. Texas

In 2005, Puerto Rico repealed its sodomy law, and in 2006, Missouri repealed its law against "homosexual conduct". In 2013, Montana removed "sexual contact or sexual intercourse between two persons of the same sex" from its definition of deviate sexual conduct, Virginia repealed its lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute, and sodomy was legalized in the US armed forces.

In 2005, basing its decision on Lawrence, the Supreme Court of Virginia in Martin v. Ziherl invalidated § 18.2-344, the Virginia statute making fornication between unmarried persons a crime.

On January 31, 2013, the Senate of Virginia passed a bill repealing § 18.2-345, the lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute enacted in 1877. On February 20, 2013, the Virginia House of Delegates passed the bill by a vote of 62 to 25 votes. On March 20, 2013, Governor Bob McDonnell signed the repeal of the lewd and lascivious cohabitation statute from the Code of Virginia.

On March 12, 2013, a three-judge panel of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit struck down § 18.2-361, the crimes against nature statute. On March 26, 2013, Attorney General of Virginia Ken Cuccinelli filed a petition to have the case reheard en banc, but the Court denied the request on April 10, 2013, with none of its 15 judges supporting the request. On June 25, Cuccinelli filed a petition for certiorari asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the Court of Appeals decision, which was rejected on October 7.

On February 7, 2014, the Virginia Senate voted 40-0 in favor of revising the crimes against nature statue to remove the ban on same-sex sexual relationships. On March 6, 2014, the Virginia House of Delegates voted 100-0 in favor of the bill. On April 7, the Governor submitted slightly different version of the bill. It was enacted by the Legislature on April 23, 2014. The law took effect upon passage.

Utah voted to revise its sodomy laws to include only forcible sodomy and sodomy on children rather than any sexual relations between consenting adults on February 26, 2019. Governor Gary Herbert signed the bill into law on March 26, 2019.

On May 23, 2019, the Alabama House of Representatives passed, with 101 voting yea and 3 absent, Alabama Senate Bill 320, which repeals the ban on "deviate sexual intercourse". On May 28, 2019, the Alabama State Senate passed Alabama Senate Bill 320, with 32 yea and 3 absent. The bill took effect on September 1, 2019. Alabama is the southernmost continental state to repeal their sodomy law as of 2023.

Maryland voted to repeal its sodomy law on March 18, 2020. The bill became law in May 2020 without the signature of Governor Larry Hogan. While the original text of the bill intended to repeal both the state's sodomy law and unnatural or perverted sexual practice law, amendments from the Maryland Senate urged to solely repeal the sodomy law. On March 31, 2023, the Maryland legislature voted to repeal the unnatural and perverted sexual practice law. The bill was sent to Governor Wes Moore for signature. As he did not veto the bill within 30 days of passage, Moore allowed for the bill to become law without his signature, with the repeal set to take effect on October 1, 2023.

Idaho repealed its sodomy law in March 2022. The repeal was a result of a lawsuit brought on in September 2020 by a plaintiff known as John Doe. John Doe alleged his constitutional rights were violated when he was forced to register as a sex offender upon moving to Idaho due to a conviction for "oral sex" two decades prior.

On May 17, 2023, the Minnesota legislature passed an Omnibus Judiciary and Public Safety Bill that included provisions repealing the state's sodomy, adultery, fornication, and abortion laws. On May 19, the Governor signed the bill into law. It took effect the following day.

Remaining defunct statutes since Lawrence v. Texas

Louisiana's statutes still include "unnatural carnal copulation by a human being with another of the same sex" in their definition of "crimes against nature", punishable (in theory) by a fine of up to $2,000 or a prison sentence of up to five years, with or without hard labor; however, this section was further mooted by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in 2005 in light of the Lawrence decision.

In State v. Whiteley (2005), the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that the crime against nature statute, N.C. G.S. § 14-177, is not unconstitutional on its face because it may properly be used to criminalize sexual conduct involving minors, non-consensual or coercive conduct, public conduct, and prostitution.

In April 2014, a proposed Louisiana bill sought to revise the state's crime against nature law, maintaining the existing prohibition against sodomy during the commission of rape and child sex abuse, and against sex with animals, but removing the unconstitutional prohibition against sex between consenting adults. The bill was defeated on April 15, 2014 by a vote of 66 to 27.

In March 2023, the Texas House committee on Criminal Jurisprudence unanimously passed House Bill 2055 that would repeal its “homosexual conduct” law criminalizing gay sex. The bill’s author, Rep. Venton Jones, D-Dallas, agreed to amend the bill to keep portions of current law that say “homosexuality is not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public” in order to get it passed out of committee. It did not receive a vote in the State House before the deadline.

As of May 2023, 12 states either have not yet formally repealed their laws against sexual activity among consenting adults or have not revised them to accurately reflect their true scope as a result of Lawrence v. Texas. Often, the sodomy law was drafted to also encompass other forms of sexual conduct such as bestiality, and no attempt has subsequently succeeded in separating them. Nine states' statutes purport to ban all forms of sodomy, some including oral intercourse, regardless of the participants' genders: Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma and South Carolina. Three states specifically target their statutes at same-sex relations only: Kansas, Kentucky, and Texas.

- Florida (Fld. Stat. 800.02.)

- Georgia (O.C.G.A. § 16-6-2)

- Kansas (Kan. Stat. 21-3505.)

- Kentucky (KY Rev Stat § 510.100.)

- Louisiana (R.S. 14:89.)

- Massachusetts (MGL Ch. 272, § 34.) (MGL Ch. 272, § 35.) – 2023 repeal bill

- Michigan (MCL § 750.158.) (MCL § 750.338.) (MCL § 750.338a.) (MCL § 750.338b.) – 2023 partial repeal bill

- Mississippi (Miss. Code § 97-29-59.)

- North Carolina (G.S. § 14-177.)

- Oklahoma (§21-886.)

- South Carolina (S.C. Code § 16-15-60.)

- Texas (Tx. Penal Code § 21.06.)

Researchers have shown that sodomy law repeals led to a decline in the number of arrests for disorderly conduct, prostitution, and other sex offenses, as well as a reduction in arrests for drug and alcohol consumption, in line with the hypothesis that sodomy law repeals enhanced mental health and lessened minority stress.

Federal law

Sodomy laws in the United States were largely a matter of state rather than federal jurisdiction, except for laws governing the District of Columbia and the U.S. Armed Forces.

District of Columbia

In 1801, the 6th United States Congress enacted the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, a law that continued all criminal laws of Maryland and Virginia, with those of Maryland applying to the portion of the District ceded from Maryland and those of Virginia applying to the portion ceded from Virginia. As a result, in the Maryland-ceded portion, sodomy was punishable with up to seven years' imprisonment for free persons and with the death penalty for enslaved persons, whereas in the Virginia-ceded portion it was punishable between one and ten years' imprisonment for free persons and with the death penalty for enslaved persons. Maryland repealed the death penalty for slaves in 1809 and modified the penalty for all persons to match Virginia's terms of imprisonment. In 1847, the Virginia-ceded portion was given back to Virginia, thus only the Maryland law had effect in the district.

In 1871, Congress enacted the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871, a law that reorganized the district government and granted it home rule. All existing laws were retained unless and until expressly altered by the new city council. Direct rule was reinstated in 1874. In Pollard v. Lyon (1875), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a District of Columbia U.S. District Court ruling that spoken words by the defendant in the case that accused the plaintiff of fornication were not actionable for slander because fornication, although involving moral turpitude, was not an indictable offense in the District of Columbia at the time as it had not been an indictable offense in Maryland since 1785 (when a provincial law passed in 1715 that banned both fornication and adultery saw only its fornication prohibition repealed). The criminal status of sodomy became ambiguous until 1901, when Congress passed legislation recognizing common law crimes, punishable with up to five years' imprisonment and/or a fine of $1,000.

In 1935, Congress made it a crime in the district to solicit a person "for the purpose of prostitution, or any other immoral or lewd purpose". In 1948, Congress enacted the first law specific to sodomy in the district, which established a penalty of up to 10 years in prison or a fine of up to $1,000, regardless of sexuality. Oral sex was included in the law's application. Also included with this law was a psychopathic offender law and a law "to provide for the treatment of sexual psychopaths". The metropolitan police department eventually had several officers whose sole job was to "check on homosexuals". Multiple court cases dealt with the issue in the following years. Many of the published sodomy and solicitation cases during the 1950s and 1960s reveal clear entrapment policies by the local police, some of which were disallowed by reviewing courts. In 1972, settling the case of Schaefers et al. v. Wilson, the D.C. government announced its intention not to prosecute anyone for private, consensual adult sodomy, an action disputed by the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia. The action came as part of a stipulation agreement in a court challenge to the sodomy law brought by four gay men.

In 1973, Congress again granted the district home rule through the District of Columbia Home Rule Act. It provided for a new city council that could pass its own laws. However laws regarding certain topics, such as changes to the criminal code, were restricted until 1977. All laws passed by the D.C. government are subject to a mandatory 30-day "congressional review" by Congress. If they are not blocked, then they become law. In 1981, the D.C. government enacted a law that repealed the sodomy law, as well as other consensual acts, and made the sexual assault laws gender neutral. However, the Congress overturned the new law. A successful legislative repeal of the law followed in 1993. This time, Congress did not interfere. In 1995, all references to sodomy were completely removed from the criminal code, and in 2004, the D.C. government repealed an outdated law against fornication.

Military

Although the U.S. military discharged soldiers for homosexual acts throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century, U.S. military law did not expressly prohibit homosexuality or homosexual conduct until February 4, 1921.

On March 1, 1917, the Articles of War of 1916 were implemented. This included a revision of the Articles of War of 1806, the new regulations detail statutes governing U.S. military discipline and justice. Under the category Miscellaneous Crimes and Offences, Article 93 states that any person subject to military law who commits "assault with intent to commit sodomy" shall be punished as a court-martial may direct.

On June 4, 1920, Congress modified Article 93 of the Articles of War of 1916. It was changed to make the act of sodomy itself a crime, separate from the offense of assault with intent to commit sodomy. It went into effect on February 4, 1921.

On May 5, 1950, the Uniform Code of Military Justice was passed by Congress and was signed into law by President Harry S. Truman, and became effective on May 31, 1951. Article 125 forbids sodomy among all military personnel, defining it as "any person subject to this chapter who engages in unnatural carnal copulation with another person of the same or opposite sex or with an animal is guilty of sodomy. Penetration, however slight, is sufficient to complete the offence."

As for the U.S. Armed Forces, the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces has ruled that the Lawrence v. Texas decision applies to Article 125, severely narrowing the previous ban on sodomy. In both United States v. Stirewalt and United States v. Marcum, the court ruled that the "conduct [consensual sodomy] falls within the liberty interest identified by the Supreme Court," but went on to say that despite the application of Lawrence to the military, Article 125 can still be upheld in cases where there are "factors unique to the military environment" that would place the conduct "outside any protected liberty interest recognized in Lawrence." Examples of such factors include rape, fraternization, public sexual behavior, or any other factors that would adversely affect good order and discipline. Convictions for consensual sodomy have been overturned in military courts under Lawrence in both United States v. Meno and United States v. Bullock.

Repeal

On December 26, 2013, President Barack Obama signed into law the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014, which repealed the ban on consensual sodomy found in Article 125.