From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The environmental impact of fracking is related to land use and water consumption, air emissions, including methane emissions,

brine and fracturing fluid leakage, water contamination, noise

pollution, and health. Water and air pollution are the biggest risks to

human health from fracking. Research has determined that fracking negatively affects human health and drives climate change.

Fracking fluids include proppants and other substances, which include chemicals known to be toxic, as well as unknown chemicals that may be toxic. In the United States, such additives may be treated as trade secrets

by companies who use them. Lack of knowledge about specific chemicals

has complicated efforts to develop risk management policies and to study

health effects.

In other jurisdictions, such as the United Kingdom, these chemicals

must be made public and their applications are required to be

nonhazardous.

Water usage by fracking can be a problem in areas that experience water shortage. Surface water

may be contaminated through spillage and improperly built and

maintained waste pits, in jurisdictions where these are permitted. Further, ground water

can be contaminated if fracturing fluids and formation fluids are able

to escape during fracking. However, the possibility of groundwater

contamination from the fracturing fluid upward migration is negligible,

even in a long-term period. Produced water, the water that returns to the surface after fracking, is managed by underground injection, municipal and commercial wastewater treatment, and reuse in future wells.

There is potential for methane to leak into ground water and the air,

though escape of methane is a bigger problem in older wells than in

those built under more recent legislation.

Fracking causes induced seismicity called microseismic events or microearthquakes.

The magnitude of these events is too small to be detected at the

surface, being of magnitude M-3 to M-1 usually. However, fluid disposal

wells (which are often used in the USA to dispose of polluted waste from

several industries) have been responsible for earthquakes up to 5.6M in

Oklahoma and other states.

Governments worldwide are developing regulatory frameworks to assess and manage

environmental and associated health risks, working under pressure from

industry on the one hand, and from anti-fracking groups on the other. In some countries like France a precautionary approach has been favored and fracking has been banned. The United Kingdom's regulatory framework

is based on the conclusion that the risks associated with fracking are

manageable if carried out under effective regulation and if operational

best practices are implemented. It has been suggested by the authors of meta-studies that in order to avoid further negative impacts, greater adherence to regulation and safety procedures are necessary.

Air emissions

A report for the European Union on the potential risks was produced in 2012. Potential risks are "methane

emissions from the wells, diesel fumes and other hazardous pollutants,

ozone precursors or odours from hydraulic fracturing equipment, such as

compressors, pumps, and valves". Also gases and hydraulic fracturing

fluids dissolved in flowback water pose air emissions risks.

One study measured various air pollutants weekly for a year surrounding

the development of a newly fractured gas well and detected nonmethane hydrocarbons, methylene chloride (a toxic solvent), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. These pollutants have been shown to affect fetal outcomes.

The relationship between hydraulic fracturing and air quality can

influence acute and chronic respiratory illnesses, including

exacerbation of asthma (induced by airborne particulates, ozone and

exhaust from equipment used for drilling and transport) and COPD. For

example, communities overlying the Marcellus shale

have higher frequencies of asthma. Children, active young adults who

spend time outdoors, and the elderly are particularly vulnerable. OSHA

has also raised concerns about the long-term respiratory effects of

occupational exposure to airborne silica at hydraulic fracturing sites. Silicosis can be associated with systemic autoimmune processes.

"In the UK, all oil and gas operators must minimise the release of gases as a condition of their licence from the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). Natural gas may only be vented for safety reasons."

Also transportation of necessary water volume for hydraulic fracturing, if done by trucks, can cause emissions. Piped water supplies can reduce the number of truck movements necessary.

A report from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection indicated that there is little potential for radiation exposure from oil and gas operations.

Air pollution is of particular concern to workers at hydraulic

fracturing well sites as the chemical emissions from storage tanks and

open flowback pits combine with the geographically compounded air concentrations from surrounding wells. Thirty seven percent of the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing operations are volatile and can become airborne.

Researchers Chen and Carter from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville used atmospheric dispersion models

(AERMOD) to estimate the potential exposure concentration of emissions

for calculated radial distances of 5 m to 180m from emission sources.

The team examined emissions from 60,644 hydraulic fracturing wells and

found “results showed the percentage of wells and their potential acute

non-cancer, chronic non-cancer, acute cancer, and chronic cancer risks

for exposure to workers were 12.41%, 0.11%, 7.53%, and 5.80%,

respectively. Acute and chronic cancer risks were dominated by emissions

from the chemical storage tanks within a 20 m radius.

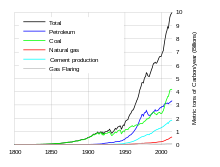

Climate change

Hydraulic fracturing is a driver of climate change. However, whether natural gas produced by hydraulic fracturing causes

higher well-to-burner emissions than gas produced from conventional

wells is a matter of contention. Some studies have found that hydraulic

fracturing has higher emissions due to methane released during

completing wells as some gas returns to the surface, together with the

fracturing fluids. Depending on their treatment, the well-to-burner

emissions are 3.5%–12% higher than for conventional gas.

A debate has arisen particularly around a study by professor Robert W. Howarth finding shale gas significantly worse for global warming than oil or coal. Other researchers have criticized Howarth's analysis, including Cathles et al., whose estimates were substantially lower." A 2012 industry funded report co-authored by researchers at the United States Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory

found emissions from shale gas, when burned for electricity, were "very

similar" to those from so-called "conventional well" natural gas, and

less than half the emissions of coal.

Studies which have estimated lifecycle methane leakage from natural gas development and production have found a wide range of leakage rates. According to the Environmental Protection Agency's Greenhouse Gas Inventory, the methane leakage rate is about 1.4%. A 16-part assessment of methane leakage from natural gas production initiated by the Environmental Defense Fund

found that fugitive emissions in key stages of the natural gas

production process are significantly higher than estimates in the EPA's

national emission inventory, with a leakage rate of 2.3 percent of overall natural gas output.

Water consumption

Massive hydraulic fracturing typical of shale wells uses between 1.2 and 3.5 million US gallons (4,500 and 13,200 m3) of water per well, with large projects using up to 5 million US gallons (19,000 m3). Additional water is used when wells are refractured. An average well requires 3 to 8 million US gallons (11,000 to 30,000 m3) of water over its lifetime. According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, greater volumes of fracturing fluids are required in Europe, where the shale depths average 1.5 times greater than in the U.S.

Whilst the published amounts may seem large, they are small in

comparison with the overall water usage in most areas. A study in Texas,

which is a water shortage area, indicates "Water use for shale gas is

<1% of statewide water withdrawals; however, local impacts vary with water availability and competing demands."

A report by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering shows the usage expected for hydraulic fracturing a well is approximately the amount needed to run a 1,000 MW coal-fired power plant for 12 hours. A 2011 report from the Tyndall Centre estimates that to support a 9 billion cubic metres per annum (320×109 cu ft/a) gas production industry, between 1.25 to 1.65 million cubic metres (44×106 to 58×106 cu ft) would be needed annually, which amounts to 0.01% of the total water abstraction nationally.

Concern has been raised over the increasing quantities of water

for hydraulic fracturing in areas that experience water stress. Use of

water for hydraulic fracturing can divert water from stream flow, water supplies for municipalities and industries such as power generation, as well as recreation and aquatic life. The large volumes of water required for most common hydraulic fracturing methods have raised concerns for arid regions, such as the Karoo in South Africa, and in drought-prone Texas, in North America. It may also require water overland piping from distant sources.

A 2014 life cycle analysis of natural gas electricity by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory

concluded that electricity generated by natural gas from massive

hydraulically fractured wells consumed between 249 gallons per

megawatt-hour (gal/MWhr) (Marcellus trend) and 272 gal/MWhr (Barnett

Shale). The water consumption for the gas from massive hydraulic

fractured wells was from 52 to 75 gal/MWhr greater (26 percent to 38

percent greater) than the 197 gal/MWhr consumed for electricity from

conventional onshore natural gas.

Some producers have developed hydraulic fracturing techniques that could reduce the need for water. Using carbon dioxide, liquid propane or other gases instead of water have been proposed to reduce water consumption.

After it is used, the propane returns to its gaseous state and can be

collected and reused. In addition to water savings, gas fracturing

reportedly produces less damage to rock formations that can impede

production. Recycled flowback water can be reused in hydraulic fracturing.

It lowers the total amount of water used and reduces the need to

dispose of wastewater after use. The technique is relatively expensive,

however, since the water must be treated before each reuse and it can

shorten the life of some types of equipment.

Water contamination

Injected fluid

In the United States, hydraulic fracturing fluids include proppants, radionuclide tracers, and other chemicals, many of which are toxic.

The type of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing and their

properties vary. While most of them are common and generally harmless,

some chemicals are carcinogenic.

Out of 2,500 products used as hydraulic fracturing additives in the

United States, 652 contained one or more of 29 chemical compounds which

are either known or possible human carcinogens, regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act for their risks to human health, or listed as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act.

Another 2011 study identified 632 chemicals used in United States

natural gas operations, of which only 353 are well-described in the

scientific literature.

A study that assessed health effects of chemicals used in fracturing

found that 73% of the products had between 6 and 14 different adverse

health effects including skin, eye, and sensory organ damage;

respiratory distress including asthma; gastrointestinal and liver

disease; brain and nervous system harms; cancers; and negative

reproductive effects.

An expansive study conducted by the Yale School of Public Health

in 2016 found numerous chemicals involved in or released by hydraulic

fracturing are carcinogenic.

Of the 119 compounds identified in this study with sufficient data,

“44% of the water pollutants...were either confirmed or possible

carcinogens.” However, the majority of chemicals lacked sufficient data

on carcinogenic potential, highlighting the knowledge gap in this area.

Further research is needed to identify both carcinogenic potential of

chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing and their cancer risk.

The European Union regulatory regime requires full disclosure of all additives.

According to the EU groundwater directive of 2006, "in order to protect

the environment as a whole, and human health in particular, detrimental

concentrations of harmful pollutants in groundwater must be avoided,

prevented or reduced." In the United Kingdom, only chemicals that are "non hazardous in their application" are licensed by the Environment Agency.

Flowback

Less than half of injected water is recovered as flowback or later production brine, and in many cases recovery is <30%.

As the fracturing fluid flows back through the well, it consists of

spent fluids and may contain dissolved constituents such as minerals and

brine waters. In some cases, depending on the geology of the formation, it may contain uranium, radium, radon and thorium. Estimates of the amount of injected fluid returning to the surface range from 15-20% to 30–70%.

Approaches to managing these fluids, commonly known as produced water, include underground injection, municipal and commercial wastewater treatment and discharge, self-contained systems at well sites or fields, and recycling to fracture future wells. The vacuum multi-effect membrane distillation system as a more effective treatment system has been proposed for treatment of flowback.

However, the quantity of waste water needing treatment and the

improper configuration of sewage plants have become an issue in some

regions of the United States. Part of the wastewater from hydraulic

fracturing operations is processed there by public sewage treatment

plants, which are not equipped to remove radioactive material and are

not required to test for it.

Produced water spills and subsequent contamination of groundwater

also presents a risk for exposure to carcinogens. Research that modeled

the solute transport of BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) and naphthalene

for a range of spill sizes on contrasting soils overlying groundwater

at different depths found that benzene and toluene were expected to

reach human health relevant concentration in groundwater because of

their high concentrations in produced water, relatively low solid/liquid

partition coefficient and low EPA drinking water limits for these

contaminants.

Benzene is a known carcinogen which affects the central nervous system

in the short term and can affect the bone marrow, blood production,

immune system, and urogenital systems with long term exposure.

Surface spills

Surface spills related to the hydraulic fracturing occur mainly because of equipment failure or engineering misjudgments.

Volatile chemicals held in waste water evaporation ponds can

evaporate into the atmosphere, or overflow. The runoff can also end up

in groundwater systems. Groundwater may become contaminated

by trucks carrying hydraulic fracturing chemicals and wastewater if

they are involved in accidents on the way to hydraulic fracturing sites

or disposal destinations.

In the evolving European Union legislation, it is required that

"Member States should ensure that the installation is constructed in a

way that prevents possible surface leaks and spills to soil, water or

air."

Evaporation and open ponds are not permitted. Regulations call for all

pollution pathways to be identified and mitigated. The use of chemical

proof drilling pads to contain chemical spills is required. In the UK,

total gas security is required, and venting of methane is only permitted

in an emergency.

Methane

In September 2014, a study from the US Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences released a report that indicated that methane contamination

can be correlated to distance from a well in wells that were known to

leak. This however was not caused by the hydraulic fracturing process,

but by poor cementation of casings.

Groundwater methane contamination has adverse effect on water quality and in extreme cases may lead to potential explosion. A scientific study conducted by researchers of Duke University

found high correlations of gas well drilling activities, including

hydraulic fracturing, and methane pollution of the drinking water. According to the 2011 study of the MIT Energy Initiative,

"there is evidence of natural gas (methane) migration into freshwater

zones in some areas, most likely as a result of substandard well

completion practices i.e. poor quality cementing job or bad casing, by a

few operators."

A 2013 Duke study suggested that either faulty construction (defective

cement seals in the upper part of wells, and faulty steel linings within

deeper layers) combined with a peculiarity of local geology may be

allowing methane to seep into waters; the latter cause may also release injected fluids to the aquifer. Abandoned gas and oil wells also provide conduits to the surface in areas like Pennsylvania, where these are common.

A study by Cabot Oil and Gas

examined the Duke study using a larger sample size, found that methane

concentrations were related to topography, with the highest readings

found in low-lying areas, rather than related to distance from gas

production areas. Using a more precise isotopic analysis, they showed

that the methane found in the water wells came from both the formations

where hydraulic fracturing occurred, and from the shallower formations. The Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission investigates complaints from water well owners, and has found some wells to contain biogenic methane unrelated to oil and gas wells, but others that have thermogenic methane due to oil and gas wells with leaking well casing.

A review published in February 2012 found no direct evidence that

hydraulic fracturing actual injection phase resulted in contamination of

ground water, and suggests that reported problems occur due to leaks in

its fluid or waste storage apparatus; the review says that methane in

water wells in some areas probably comes from natural resources.

Another 2013 review found that hydraulic fracturing technologies

are not free from risk of contaminating groundwater, and described the

controversy over whether the methane that has been detected in private

groundwater wells near hydraulic fracturing sites has been caused by

drilling or by natural processes.

Radionuclides

There are naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM), for example radium, radon, uranium, and thorium, in shale deposits.

Brine co-produced and brought to the surface along with the oil and gas

sometimes contains naturally occurring radioactive materials; brine

from many shale gas wells, contains these radioactive materials.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and regulators in North Dakota

consider radioactive material in flowback a potential hazard to workers

at hydraulic fracturing drilling and waste disposal sites and those

living or working nearby if the correct procedures are not followed.

A report from the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection

indicated that there is little potential for radiation exposure from oil

and gas operations.

Land use

In

the UK, the likely well spacing visualised by the December 2013 DECC

Strategic Environmental Assessment report indicated that well pad

spacings of 5 km were likely in crowded areas, with up to 3 hectares

(7.4 acres) per well pad. Each pad could have 24 separate wells. This

amounts to 0.16% of land area.

A study published in 2015 on the Fayetteville Shale found that a

mature gas field impacted about 2% of the land area and substantially

increased edge habitat creation. Average land impact per well was 3

hectares (about 7 acres)

In another case study for a watershed in Ohio, lands disturbed over 20

years amount to 9.7% of the watershed area, with only 0.24% attributed

to fracking wellpad construction.

Research indicates that effects on ecosystem services costs (i.e. those

processes that the natural world provides to humanity) has reached over

$250 million per year in the U.S.

Seismicity

Hydraulic fracturing causes induced seismicity called microseismic events or microearthquakes. These microseismic events are often used to map the horizontal and vertical extent of the fracturing.

The magnitude of these events is usually too small to be detected at

the surface, although the biggest micro-earthquakes may have the

magnitude of about -1.5 (Mw).

Induced seismicity from hydraulic fracturing

As of August 2016, there were at least nine known cases of fault reactivation by hydraulic fracturing that caused induced seismicity strong enough to be felt by humans at the surface: In Canada, there have been three in Alberta (M 4.8 and M 4.4 and M 4.4) and three in British Columbia (M 4.6, M 4.4 and M 3.8); In the United States there has been: one in Oklahoma (M 2.8) and one in Ohio (M 3.0), and; In the United Kingdom, there have been two in Lancashire (M 2.3 and M 1.5).

Induced seismicity from water disposal wells

According

to the USGS only a small fraction of roughly 30,000 waste fluid

disposal wells for oil and gas operations in the United States have

induced earthquakes that are large enough to be of concern to the

public.

Although the magnitudes of these quakes has been small, the USGS says

that there is no guarantee that larger quakes will not occur.

In addition, the frequency of the quakes has been increasing. In 2009,

there were 50 earthquakes greater than magnitude 3.0 in the area

spanning Alabama and Montana, and there were 87 quakes in 2010. In 2011

there were 134 earthquakes in the same area, a sixfold increase over

20th century levels.

There are also concerns that quakes may damage underground gas, oil,

and water lines and wells that were not designed to withstand

earthquakes.

A 2012 US Geological Survey study reported that a "remarkable"

increase in the rate of M ≥ 3 earthquakes in the US midcontinent "is

currently in progress", having started in 2001 and culminating in a

6-fold increase over 20th century levels in 2011. The overall increase

was tied to earthquake increases in a few specific areas: the Raton

Basin of southern Colorado (site of coalbed methane activity), and gas-producing areas in central and southern Oklahoma, and central Arkansas.

While analysis suggested that the increase is "almost certainly

man-made", the USGS noted: "USGS's studies suggest that the actual

hydraulic fracturing process is only very rarely the direct cause of

felt earthquakes." The increased earthquakes were said to be most likely

caused by increased injection of gas-well wastewater into disposal

wells.

The injection of waste water from oil and gas operations, including

from hydraulic fracturing, into saltwater disposal wells may cause

bigger low-magnitude tremors, being registered up to 3.3 (Mw).

Noise

Each well

pad (in average 10 wells per pad) needs during preparatory and hydraulic

fracturing process about 800 to 2,500 days of activity, which may

affect residents. In addition, noise is created by transport related to

the hydraulic fracturing activities.

Noise pollution from hydraulic fracturing operations (e.g., traffic,

flares/burn-offs) is often cited as a source of psychological distress,

as well as poor academic performance in children. For example, the low-frequency noise that comes from well pumps contributes to irritation, unease, and fatigue.

The UK Onshore Oil and Gas (UKOOG) is the industry representative

body, and it has published a charter that shows how noise concerns will

be mitigated, using sound insulation, and heavily silenced rigs where

this is needed.

Safety issues

In July 2013, the United States Federal Railroad Administration listed oil contamination by hydraulic fracturing chemicals as "a possible cause" of corrosion in oil tank cars.

Impacted

communities are often already vulnerable, including poor, rural, or

indigenous persons, who may continue to experience the deleterious

effects of hydraulic fracturing for generations. Competition for

resources between farmers and oil companies contributes to stress for

agricultural workers and their families, as well as to a community-level

“us versus them” mentality that creates community distress (Morgan et

al. 2016). Rural communities that host hydraulic fracturing operations

often experience a “boom/bust cycle,” whereby their population surges,

consequently exerting stress on community infrastructure and service

provision capabilities (e.g., medical care, law enforcement).

Indigenous and agricultural communities may be particularly

impacted by hydraulic fracturing, given their historical attachment to,

and dependency on, the land they live on, which is often damaged as a

result of the hydraulic fracturing process.

Native Americans, particularly those living on rural reservations, may

be particularly vulnerable to the effects of fracturing; that is, on the

one hand, tribes may be tempted to engage with the oil companies to

secure a source of income but, on the other hand, must often engage in

legal battles to protect their sovereign rights and the natural

resources of their land.

Policy and science

There are two main approaches to regulation that derive from policy debates about how to manage risk and a corresponding debate about how to assess risk.

The two main schools of regulation are science-based assessment

of risk and the taking of measures to prevent harm from those risks

through an approach like hazard analysis, and the precautionary principle, where action is taken before risks are well-identified. The relevance and reliability of risk assessments

in communities where hydraulic fracturing occurs has also been debated

amongst environmental groups, health scientists, and industry leaders.

The risks, to some, are overplayed and the current research is

insufficient in showing the link between hydraulic fracturing and

adverse health effects, while to others the risks are obvious and risk assessment is underfunded.

Different regulatory approaches have thus emerged. In France and Vermont for instance, a precautionary approach has been favored and hydraulic fracturing has been banned based on two principles: the precautionary principle and the prevention principle. Nevertheless, some States such as the U.S. have adopted a risk assessment approach, which had led to many regulatory debates over the issue of hydraulic fracturing and its risks.

In the UK, the regulatory framework is largely being shaped by a

report commissioned by the UK Government in 2012, whose purpose was to

identify the problems around hydraulic fracturing and to advise the

country's regulatory agencies. Jointly published by the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Engineering, under the chairmanship of Professor Robert Mair, the report features ten recommendations covering issues such as groundwater contamination,

well integrity, seismic risk, gas leakages, water management,

environmental risks, best practice for risk management, and also

includes advice for regulators and research councils.

The report was notable for stating that the risks associated with

hydraulic fracturing are manageable if carried out under effective

regulation and if operational best practices are implemented.

A 2013 review concluded that, in the US, confidentiality

requirements dictated by legal investigations have impeded peer-reviewed

research into environmental impacts.

There are numerous scientific limitations to the study of the

environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing. The main limitation is the

difficulty in developing effective monitoring procedures and protocols,

for which there are several main reasons:

- Variability among fracturing sites in terms of ecosystems,

operation sizes, pad densities, and quality-control measures makes it

difficult to develop a standard protocol for monitoring.

- As more fracturing sites develop, the chance for interaction between

sites increases, greatly compounding the effects and making monitoring

of one site difficult to control. These cumulative effects can be

difficult to measure, as many of the impacts develop very slowly.

- Due to the vast number of chemicals involved in hydraulic

fracturing, developing baseline data is challenging. In addition, there

is a lack of research on the interaction of the chemicals used in

hydraulic fracturing fluid and the fate of the individual components.