A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions. Some authorities restrict the use of the term to bodies deliberately embalmed with chemicals, but the use of the word to cover accidentally desiccated bodies goes back to at least 1615 AD.

Mummies of humans and animals have been found on every continent, both as a result of natural preservation through unusual conditions, and as cultural artifacts. Over one million animal mummies have been found in Egypt, many of which are cats. Many of the Egyptian animal mummies are sacred ibis, and radiocarbon dating suggests the Egyptian ibis mummies that have been analyzed were from a time frame that falls between approximately 450 and 250 BC.

In addition to the mummies of ancient Egypt, deliberate mummification was a feature of several ancient cultures in areas of America and Asia with very dry climates. The Spirit Cave mummies of Fallon, Nevada, in North America were accurately dated at more than 9,400 years old. Before this discovery, the oldest known deliberate mummy was a child, one of the Chinchorro mummies found in the Camarones Valley, Chile, which dates around 5050 BC. The oldest known naturally mummified human corpse is a severed head dated as 6,000 years old, found in 1936 AD at the site named Inca Cueva No. 4 in South America.

Etymology and meaning

The English word mummy is derived from medieval Latin Mumia, a borrowing of the medieval Arabic word mūmiya (مومياء) which meant an embalmed corpse, as well as the bituminous embalming substance. This word was borrowed from Persian where it meant asphalt, and is derived from the word mūm meaning wax. The meaning of "corpse preserved by desiccation" developed post-medievally. The Medieval English term "mummy" was defined as "medical preparation of the substance of mummies", rather than the entire corpse, with Richard Hakluyt in 1599 AD complaining that "these dead bodies are the Mummy which the Phisistians and Apothecaries doe against our willes make us to swallow". These substances were called mummia.

The OED defines a mummy as "the body of a human being or animal embalmed (according to the ancient Egyptian or some analogous method) as a preparation for burial", citing sources from 1615 AD onward. However, Chamber's Cyclopædia and the Victorian zoologist Francis Trevelyan Buckland define a mummy as follows: "A human or animal body desiccated by exposure to sun or air. Also applied to the frozen carcase of an animal imbedded in prehistoric snow".

Wasps of the genus Aleiodes are known as "mummy wasps" because they wrap their caterpillar prey as "mummies".

History of mummy studies

While interest in the study of mummies dates as far back as Ptolemaic Greece, most structured scientific study began at the beginning of the 20th century. Prior to this, many rediscovered mummies were sold as curiosities or for use in pseudoscientific novelties such as mummia. The first modern scientific examinations of mummies began in 1901, conducted by professors at the English-language Government School of Medicine in Cairo, Egypt. The first X-ray of a mummy came in 1903, when professors Grafton Elliot Smith and Howard Carter used the only X-ray machine in Cairo at the time to examine the mummified body of Thutmose IV. British chemist Alfred Lucas applied chemical analyses to Egyptian mummies during this same period, which returned many results about the types of substances used in embalming. Lucas also made significant contributions to the analysis of Tutankhamun in 1922.

Pathological study of mummies saw varying levels of popularity throughout the 20th century. In 1992, the First World Congress on Mummy Studies was held in Puerto de la Cruz on Tenerife in the Canary Islands. More than 300 scientists attended the Congress to share nearly 100 years of collected data on mummies. The information presented at the meeting triggered a new surge of interest in the subject, with one of the major results being the integration of biomedical and bioarchaeological information on mummies with existing databases. This was not possible prior to the Congress due to the unique and highly specialized techniques required to gather such data.

In more recent years, CT scanning has become an invaluable tool in the study of mummification by allowing researchers to digitally "unwrap" mummies without risking damage to the body. The level of detail in such scans is so intricate that small linens used in tiny areas such as the nostrils can be digitally reconstructed in 3-D. Such modelling has been utilized to perform digital autopsies on mummies to determine the cause of death and lifestyle, such as in the case of Tutankhamun.

Types

Mummies are typically divided into one of two distinct categories: anthropogenic or spontaneous. Anthropogenic mummies were deliberately created by the living for any number of reasons, the most common being for religious purposes. Spontaneous mummies, such as Ötzi, were created unintentionally due to natural conditions such as extremely dry heat or cold, or acidic and anaerobic conditions such as those found in bogs. While most individual mummies exclusively belong to one category or the other, there are examples of both types being connected to a single culture, such as those from the ancient Egyptian culture and the Andean cultures of South America. Some of the later well-preserved corpses of the mummification were found under Christian churches, such as the mummified vicar Nicolaus Rungius found under the St. Michael Church in Keminmaa, Finland. There are also cases that fall outside of these categories.

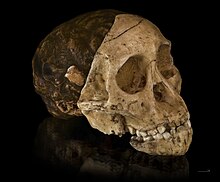

Egyptian mummies

Until recently, it was believed that the earliest ancient Egyptian mummies were created naturally due to the environment in which they were buried. In 2014, an 11-year study by the University of York, Macquarie University and the University of Oxford suggested that artificial mummification occurred 1,500 years earlier than first thought. This was confirmed in 2018, when tests on a 5,600-year-old mummy in Turin revealed that it had been deliberately mummified using linen wrappings and embalming oils made from conifer resin and aromatic plant extracts.

The preservation of the dead had a profound effect on ancient Egyptian religion. Mummification was an integral part of the rituals for the dead beginning as early as the 2nd dynasty (about 2800 BC). Egyptians saw the preservation of the body after death as an important step to living well in the afterlife. As Egypt gained more prosperity, burial practices became a status symbol for the wealthy as well. This cultural hierarchy led to the creation of elaborate tombs, and more sophisticated methods of embalming.

By the 4th dynasty (about 2600 BC) Egyptian embalmers began to achieve "true mummification" through a process of evisceration. Much of this early experimentation with mummification in Egypt is unknown.

The few documents that directly describe the mummification process date to the Greco-Roman period. The majority of the papyri that have survived only describe the ceremonial rituals involved in embalming, not the actual surgical processes involved. A text known as The Ritual of Embalming does describe some of the practical logistics of embalming; however, there are only two known copies and each is incomplete. With regards to mummification shown in images, there are apparently also very few. The tomb of Tjay, designated TT23, is one of only two known which show the wrapping of a mummy (Riggs 2014).

Another text that describes the processes being used in the latter periods is Herodotus' Histories. Written in Book 2 of the Histories is one of the most detailed descriptions of the Egyptian mummification process, including the mention of using natron in order to dehydrate corpses for preservation. However, these descriptions are short and fairly vague, leaving scholars to infer the majority of the techniques that were used by studying mummies that have been unearthed.

By utilizing current advancements in technology, scientists have been able to uncover a plethora of new information about the techniques used in mummification. A series of CT scans performed on a 2,400-year-old mummy in 2008 revealed a tool that was left inside the cranial cavity of the skull. The tool was a rod, made of an organic material, that was used to break apart the brain to allow it to drain out of the nose. This discovery helped to dispel the claim within Herodotus' works that the rod had been a hook made of iron. Earlier experimentation in 1994 by researchers Bob Brier and Ronald Wade supported these findings. While attempting to replicate Egyptian mummification, Brier and Wade discovered that removal of the brain was much easier when the brain was liquefied and allowed to drain with the help of gravity, as opposed to trying to pull the organ out piece by piece with a hook.

Through various methods of study over many decades, modern Egyptologists now have an accurate understanding of how mummification was achieved in ancient Egypt. The first and most important step was to halt the process of decomposition, by removing the internal organs and washing out the body with a mix of spices and palm wine. The only organ left behind was the heart, as tradition held the heart was the seat of thought and feeling and would therefore still be needed in the afterlife. After cleansing, the body was then dried out with natron inside the empty body cavity as well as outside on the skin. The internal organs were also dried and either sealed in individual jars, or wrapped to be replaced within the body. This process typically took forty days.

After dehydration, the mummy was wrapped in many layers of linen cloth. Within the layers, Egyptian priests placed small amulets to guard the decedent from evil. Once the mummy was completely wrapped, it was coated in resin in order to keep the threat of moist air away. The resin was also applied to the coffin in order to seal it. The mummy was then sealed within its tomb, alongside the worldly goods that were believed to help aid it in the afterlife.

Aspergillus niger, a hardy species of fungus capable of living in a variety of environments, has been found in the mummies of ancient Egyptian tombs and can be inhaled when they are disturbed.

Mummification and rank

Mummification is one of the defining customs in ancient Egyptian society for people today. The practice of preserving the human body is believed to be a quintessential feature of Egyptian life. Yet even mummification has a history of development and was accessible to different ranks of society in different ways during different periods. There were at least three different processes of mummification according to Herodotus. They range from "the most perfect" to the method employed by the "poorer classes".

"Most perfect" method

The most expensive process was to preserve the body by dehydration and protect against pests, such as insects. Almost all of the actions Herodotus described served one of these two functions.

First, the brain was removed from the cranium through the nose; the gray matter was discarded. Modern mummy excavations have shown that instead of an iron hook inserted through the nose as Herodotus claims, a rod was used to liquefy the brain via the cranium, which then drained out the nose by gravity. The embalmers then rinsed the skull with certain drugs that mostly cleared any residue of brain tissue and also had the effect of killing bacteria. Next, the embalmers made an incision along the flank with a sharp blade fashioned from an Ethiopian stone and removed the contents of the abdomen. Herodotus does not discuss the separate preservation of these organs and their placement either in special jars or back in the cavity, a process that was part of the most expensive embalming, according to archaeological evidence.

The abdominal cavity was then rinsed with palm wine and an infusion of crushed, fragrant herbs and spices; the cavity was then filled with spices including myrrh, cassia, and, Herodotus notes, "every other sort of spice except frankincense", also to preserve the person.

The body was further dehydrated by placing it in natron, a naturally occurring salt, for 70 days. Herodotus insists that the body did not stay in the natron longer than 70 days. Any shorter time and the body would not be completely dehydrated; any longer, and the body would be too stiff to move into position for wrapping. The embalmers then washed the body again and wrapped it with linen bandages. The bandages were covered with a gum that modern research has shown is both a waterproofing agent and an antimicrobial agent.

At this point, the body was given back to the family. These "perfect" mummies were then placed in human-shaped wooden cases. Wealthy people placed these wooden cases in stone sarcophagi that provided further protection. The family placed the sarcophagus in the tomb upright against the wall, according to Herodotus.

Avoiding expense

The second process that Herodotus describes was used by middle-class people or people who "wish to avoid expense". In this method, an oil derived from cedar trees was injected with a syringe into the abdomen. A rectal plug prevented the oil from escaping. This oil probably had the dual purpose of liquefying the internal organs but also of disinfecting the abdominal cavity. (By liquefying the organs, the family avoided the expense of canopic jars and separate preservation.) The body was then placed in natron for seventy days. At the end of this time, the body was removed and the cedar oil, now containing the liquefied organs, was drained through the rectum. With the body dehydrated, it could be returned to the family. Herodotus does not describe the process of burial of such mummies, but they were perhaps placed in a shaft tomb. Poorer people used coffins fashioned from terracotta.

Inexpensive method

The third and least expensive method the embalmers offered was to clear the intestines with an unnamed liquid, injected as an enema. The body was then placed in natron for seventy days and returned to the family. Herodotus gives no further details.

Christian mummies

In Christian tradition, some bodies of saints are naturally conserved and venerated.

Mummification in other cultures

Africa

In addition to the mummies of Egypt, there have been instances of mummies being discovered in other areas of the African continent. The bodies show a mix of anthropogenic and spontaneous mummification, with some being thousands of years old.

Canary Islands

The mummies of the Canary Islands belong to the indigenous Guanche people and date to the time before 14th-century Spanish explorers settled in the area. All deceased people within the Guanche culture were mummified during this time, though the level of care taken with embalming and burial varied depending on individual social status. Embalming was carried out by specialized groups, organized according to gender, who were considered unclean by the rest of the community. The techniques for embalming were similar to those of the ancient Egyptians, involving evisceration, preservation, and stuffing of the evacuated bodily cavities, then wrapping the body in animal skins. Despite the successful techniques utilized by the Guanche, very few mummies remain due to looting and desecration.

Libya

The mummified remains of an infant were discovered during an expedition by archaeologist Fabrizio Mori to Libya during the winter of 1958–1959 in the natural cave structure of Uan Muhuggiag. After curious deposits and cave paintings were discovered on the surfaces of the cave, expedition leaders decided to excavate. Uncovered alongside fragmented animal bone tools was the mummified body of an infant, wrapped in animal skin and wearing a necklace made of ostrich egg shell beads. Professor Tongiorgi of the University of Pisa radiocarbon-dated the infant to between 5,000 and 8,000 years old. A long incision located on the right abdominal wall, and the absence of internal organs, indicated that the body had been eviscerated post-mortem, possibly in an effort to preserve the remains. A bundle of herbs found within the body cavity also supported this conclusion. Further research revealed that the child had been around 30 months old at the time of death, though gender could not be determined due to poor preservation of the sex organs.

South Africa

The first mummy to be discovered in South Africa was found in the Baviaanskloof Wilderness Area by Dr. Johan Binneman in 1999. Nicknamed Moses, the mummy was estimated to be around 2,000 years old. After being linked to the indigenous Khoi culture of the region, the National Council of Khoi Chiefs of South Africa began to make legal demands that the mummy be returned shortly after the body was moved to the Albany Museum in Grahamstown.

Asia

The mummies of Asia are usually considered to be accidental. The decedents were buried in just the right place where the environment could act as an agent for preservation. This is particularly common in the desert areas of the Tarim Basin and Iran. Mummies have been discovered in more humid Asian climates; however, these are subject to rapid decay after being removed from the grave.

China

Mummies from various dynasties throughout China's history have been discovered in several locations across the country. They are almost exclusively considered to be unintentional mummifications. Many areas in which mummies have been uncovered are difficult for preservation, due to their warm, moist climates. This makes the recovery of mummies a challenge, as exposure to the outside world can cause the bodies to decay in a matter of hours.

An example of a Chinese mummy that was preserved despite being buried in an environment not conducive to mummification is Xin Zhui. Also known as Lady Dai, she was discovered in the early 1970s at the Mawangdui archaeological site in Changsha. She was the wife of the Marquis of Dai during the Han dynasty, who was also buried with her alongside another young man often considered to be a very close relative. However, Xin Zhui's body was the only one of the three to be mummified. Her corpse was so well-preserved that surgeons from the Hunan Provincial Medical Institute were able to perform an autopsy. The exact reason why her body was so completely preserved has yet to be determined.

Among the mummies discovered in China are those termed Tarim mummies because of their discovery in the Tarim Basin. The dry desert climate of the basin proved to be an excellent agent for desiccation. For this reason, over 200 Tarim mummies, which are over 4,000 years old, were excavated from a cemetery in the present-day Xinjiang region. The mummies were found buried in upside-down boats with hundreds of 13-foot-long wooden poles in the place of tombstones. DNA sequence data shows that the mummies had Haplogroup R1a (Y-DNA) characteristic of western Eurasia in the area of East-Central Europe, Central Asia and the Indus Valley. This has created a stir in the Turkic-speaking Uighur population of the region, who claim the area has always belonged to their culture, while it was not until the 10th century that Uighurs are said by scholars to have moved to the region from Central Asia. American Sinologist Victor H. Mair claims that "the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucasoid, or Europoid" with "east Asian migrants arriving in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin around 3,000 years ago", while Mair also notes that it was not until 842 that the Uighur peoples settled in the area. Other mummified remains have been recovered from around the Tarim Basin at sites including Qäwrighul, Yanghai, Shengjindian, Shanpula (Sampul), Zaghunluq, and Qizilchoqa.

Iran

As of 2012, at least eight mummified human remains have been recovered from the Douzlakh Salt Mine at Chehr Abad in northwestern Iran. Due to their salt preservation, these bodies are collectively known as Saltmen. Carbon-14 testing conducted in 2008 dated three of the bodies to around 400 BC. Later isotopic research on the other mummies returned similar dates, however, many of these individuals were found to be from a region that is not closely associated with the mine. It was during this time that researchers determined the mine suffered a major collapse, which likely caused the death of the miners. Since there is significant archaeological data that indicates the area was not actively inhabited during this time period, current consensus holds that the accident occurred during a brief period of temporary mining activity.

Siberia

In 1993, a team of Russian archaeologists led by Dr. Natalia Polosmak discovered the Siberian Ice Maiden, a Scytho-Siberian woman, on the Ukok Plateau in the Altai Mountains near the Mongolian border. The mummy was naturally frozen due to the severe climatic conditions of the Siberian steppe. Also known as Princess Ukok, the mummy was dressed in finely detailed clothing and wore an elaborate headdress and jewelry. Alongside her body were buried six decorated horses and a symbolic meal for her last journey. Her left arm and hand were tattooed with animal style figures, including a highly stylized deer.

The Ice Maiden has been a source of some recent controversy. The mummy's skin has suffered some slight decay, and the tattoos have faded since the excavation. Some residents of the Altai Republic, formed after the breakup of the Soviet Union, have requested the return of the Ice Maiden, who is currently stored in Novosibirsk in Siberia.

Another Siberian mummy, a man, was discovered much earlier in 1929. His skin was also marked with tattoos of two monsters resembling griffins, which decorated his chest, and three partially obliterated images which seem to represent two deer and a mountain goat on his left arm.

Philippines

Philippine mummies are called Kabayan Mummies. They are common in Igorot culture and their heritage. The mummies are found in some areas named Kabayan, Sagada and among others. The mummies are dated between the 14th and 19th centuries.

Europe

The European continent is home to a diverse spectrum of spontaneous and anthropogenic mummies. Some of the best-preserved mummies have come from bogs located across the region. The Capuchin monks that inhabited the area left behind hundreds of intentionally-preserved bodies that have provided insight into the customs and cultures of people from various eras. One of the oldest mummies (nicknamed Ötzi) was discovered on this continent. New mummies continue to be uncovered in Europe well into the 21st century.

Bog bodies

Great Britain, Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark have produced a number of bog bodies, mummies of people deposited in sphagnum bogs, apparently as a result of murder or ritual sacrifices. In such cases, the acidity of the water, low temperature and lack of oxygen combined to tan the body's skin and soft tissues. The skeleton typically disintegrates over time. Such mummies are remarkably well preserved on emerging from the bog, with skin and internal organs intact; it is even possible to determine the decedent's last meal by examining stomach contents. The Haraldskær Woman was discovered by labourers in a bog in Jutland in 1835. She was erroneously identified as an early medieval Danish queen, and for that reason was placed in a royal sarcophagus at the Saint Nicolai Church, Vejle, where she currently remains. Another bog body, also from Denmark, known as the Tollund Man was discovered in 1950. The corpse was noted for its excellent preservation of the face and feet, which appeared as if the man had recently died. Only the head of Tollund Man remains, due to the decomposition of the rest of his body, which was not preserved along with the head.

Czech Republic

The majority of mummies recovered in the Czech Republic come from underground crypts. While there is some evidence of deliberate mummification, most sources state that desiccation occurred naturally due to unique conditions within the crypts.

The Capuchin Crypt in Brno contains three hundred years of mummified remains directly below the main altar. Beginning in the 18th century when the crypt was opened, and continuing until the practice was discontinued in 1787, the Capuchin friars of the monastery would lay the deceased on a pillow of bricks on the ground. The unique air quality and topsoil within the crypt naturally preserved the bodies over time.

Approximately fifty mummies were discovered in an abandoned crypt beneath the Church of St. Procopius of Sázava in Vamberk in the mid-1980s. Workers digging a trench accidentally broke into the crypt, which began to fill with waste water. The mummies quickly began to deteriorate, though thirty-four were able to be rescued and stored temporarily at the District Museum of the Orlické Mountains until they could be returned to the monastery in 2000. The mummies range in age and social status at time of death, with at least two children and one priest. The majority of the Vamberk mummies date from the 18th century.

The Klatovy catacombs currently house an exhibition of Jesuit mummies, alongside some aristocrats, that were originally interred between 1674 and 1783. In the early 1930s, the mummies were accidentally damaged during repairs, resulting in the loss of 140 bodies. The newly updated airing system preserves the thirty-eight bodies that are currently on display.

Denmark

Apart from several bog bodies, Denmark has also yielded several other mummies, such as the three Borum Eshøj mummies, the Skrydstrup Woman and the Egtved Girl, who were all found inside burial mounds, or tumuli.

In 1875, the Borum Eshøj grave mound was uncovered, which had been built around three coffins, which belonged to a middle aged man and woman as well as a man in his early twenties. Through examination, the woman was discovered to be around 50–60 years old. She was found with several artifacts made of bronze, consisting of buttons, a belt plate, and rings, showing she was of higher class. All of the hair had been removed from the skull later when farmers had dug through the casket. Her original hairstyle is unknown. The two men wore kilts, and the younger man wore a sheath which contained a bronze dagger. All three mummies were dated to 1351–1345 BC.

The Skrydstrup Woman was unearthed from a tumulus in Southern Jutland, in 1935. Carbon-14 dating showed that she had died around 1300 BC; examination also revealed that she was around 18–19 years old at the time of death, and that she had been buried in the summertime. Her hair had been drawn up in an elaborate hairstyle, which was then covered by a horse hair hairnet made by the sprang technique. She was wearing a blouse and a necklace as well as two golden earrings, showing she was of higher class.

The Egtved Girl, dated to 1370 BC, was also found inside a sealed coffin within a tumulus, in 1921. She was wearing a bodice and a skirt, including a belt and bronze bracelets. Found with the girl, at her feet, were the cremated remains of a child and, by her head, a box containing some bronze pins, a hairnet, and an awl.

Hungary

In 1994, 265 mummified bodies were found in the crypt of a Dominican church in Vác, Hungary from the 1729–1838 period. The discovery proved to be scientifically important, and by 2006 an exhibition was established in the Museum of Natural History in Budapest. Unique to the Hungarian mummies are their elaborately decorated coffins, with no two being exactly alike.

Italy

The varied geography and climatology of Italy has led to many cases of spontaneous mummification. Italian mummies display the same diversity, with a conglomeration of natural and intentional mummification spread across many centuries and cultures.

The oldest natural mummy in Europe was discovered in 1991 in the Ötztal Alps on the Austrian-Italian border. Nicknamed Ötzi, the mummy is a 5,300-year-old male believed to be a member of the Tamins-Carasso-Isera cultural group of South Tyrol. Despite his age, a recent DNA study conducted by Walther Parson of Innsbruck Medical University revealed Ötzi has 19 living genetic relatives.

The Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo were built in the 16th century by the friars of Palermo's Capuchin monastery. Originally intended to hold the deliberately mummified remains of dead friars, interment in the catacombs became a status symbol for the local population in the following centuries. Burials continued until the 1920s, with one of the final burials being that of Rosalia Lombardo. In all, the catacombs host nearly 8000 mummies.

The most recent discovery of mummies in Italy came in 2010, when sixty mummified human remains were found in the crypt of the Conversion of St Paul church in Roccapelago di Pievepelago, Italy. Built in the 15th century as a cannon hold and later converted in the 16th century, the crypt had been sealed once it had reached capacity, leaving the bodies to be protected and preserved. The crypt was reopened during restoration work on the church, revealing the diverse array of mummies inside. The bodies were quickly moved to a museum for further study.

North America

The mummies of North America are often steeped in controversy, as many of these bodies have been linked to still-existing native cultures. While the mummies provide a wealth of historically significant data, native cultures and tradition often demands the remains be returned to their original resting places. This has led to many legal actions by Native American councils, leading to most museums keeping mummified remains out of the public eye.

Canada

Kwäday Dän Ts'ìnchi ("Long ago person found" in the Southern Tutchone language of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations), was found in August 1999 by three First Nations hunters at the edge of a glacier in Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park, British Columbia, Canada. According to the Kwäday Dän Ts'ìnchi Project, the remains are the oldest well preserved mummy discovered in North America. (The Spirit Cave mummy although not well preserved, is much older.) Initial radiocarbon tests date the mummy to around 550 years-old.

Greenland

In 1972, eight remarkably preserved mummies were discovered at an abandoned Inuit settlement called Qilakitsoq, in Greenland. The "Greenland Mummies" consisted of a six-month-old baby, a four-year-old boy, and six women of various ages, who died around 500 years ago. Their bodies were naturally mummified by the sub-zero temperatures and dry winds in the cave in which they were found.

Mexico

Intentional mummification in pre-Columbian Mexico was practiced by the Aztec culture. These bodies are collectively known as Aztec mummies. Genuine Aztec mummies were "bundled" in a woven wrap and often had their faces covered by a ceremonial mask. Public knowledge of Aztec mummies increased due to traveling exhibits and museums in the 19th and 20th centuries, though these bodies were typically naturally desiccated remains and not actually the mummies associated with Aztec culture.

Natural mummification has been known to occur in several places in Mexico; this includes the mummies of Guanajuato. A collection of these mummies, most of which date to the late 19th century, have been on display at El Museo de las Momias in the city of Guanajuato since 1970. The museum claims to have the smallest mummy in the world on display (a mummified fetus). It was thought that minerals in the soil had the preserving effect, however it may rather be due to the warm, arid climate. Mexican mummies are also on display in the small town of Encarnación de Díaz, Jalisco.

United States

Spirit Cave Man was discovered in 1940 during salvage work prior to guano mining activity that was scheduled to begin in the area. The mummy is a middle-aged male, found completely dressed and lying on a blanket made of animal skin. Radiocarbon tests in the 1990s dated the mummy to being nearly 9,000 years old. The remains were held at the Nevada State Museum, though the local Native American community began petitioning to have the remains returned and reburied in 1995. When the Bureau of Land Management did not repatriate the mummy in 2000, the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe sued under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. After DNA sequencing determined that the remains were in fact related to modern Native Americans, they were repatriated to the tribe in 2016.

Oceania

Mummies from the Oceania are not limited only to Australia. Discoveries of mummified remains have also been located in New Zealand, and the Torres Strait, though these mummies have been historically harder to examine and classify. Prior to the 20th century, most literature on mummification in the region was either silent or anecdotal. However, the boom of interest generated by the scientific study of Egyptian mummification lead to more concentrated study of mummies in other cultures, including those of Oceania.

Australia

The aboriginal mummification traditions found in Australia are thought be related to those found in the Torres Strait islands, the inhabitants of which achieved a high level of sophisticated mummification techniques. Australian mummies lack some of the technical ability of the Torres Strait mummies, however much of the ritual aspects of the mummification process are similar. Full-body mummification was achieved by these cultures, but not the level of artistic preservation as found on smaller islands. The reason for this seems to be for easier transport of bodies by more nomadic tribes.

Torres Strait

The mummies of the Torres Strait have a considerably higher level of preservation technique as well as creativity compared to those found on Australia. The process began with removal of viscera, after which the bodies were set in a seated position on a platform and either left to dry in the sun or smoked over a fire in order to aid in desiccation. In the case of smoking, some tribes would collect the fat that drained from the body to mix with ocher to create red paint that would then be smeared back on the skin of the mummy. The mummies remained on the platforms, decorated with the clothing and jewelry they wore in life, before being buried.

New Zealand

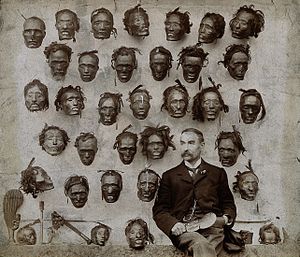

Some Māori tribes from New Zealand would keep mummified heads as trophies from tribal warfare. They are also known as Mokomokai. In the 19th century, many of the trophies were acquired by Europeans who found the tattooed skin to be a phenomenal curiosity. Westerners began to offer valuable commodities in exchange for the uniquely tattooed mummified heads. The heads were later put on display in museums, 16 of them in France alone. In 2010, the Rouen City Hall of France returned one of the heads to New Zealand, despite earlier protests by the Culture Ministry of France.

There is also evidence that some Māori tribes may have practiced full-body mummification, though the practice is not thought to have been widespread. The discussion of Māori mummification has been historically controversial, with some experts in past decades claiming that such mummies have never existed. The historical significance of full-body mummification within Māori culture is acknowledged by science, although there is still debate as to the nature of their exact mummification processes. Some mummies appear to have been spontaneously created by the natural environment, while others exhibit signs of direct human involvement. Generally, modern consensus tends to agree that there could have been a mixture of both types of mummification, similar to that of the Ancient Egyptian culture.

South America

The South American continent contains some of the oldest mummies in the world, both deliberate and accidental. The bodies were preserved by the best agent for mummification: the environment. The Pacific coastal desert in Peru and Chile is one of the driest areas in the world and the dryness facilitated mummification. Rather than developing elaborate processes such as later-dynasty ancient Egyptians, the early South Americans often left their dead in naturally dry or frozen areas, though some did perform surgical preparation when mummification was intentional. Some of the reasons for intentional mummification in South America include memorialization, immortalization, and religious offerings. A large number of mummified bodies have been found in pre-Columbian cemeteries scattered around Peru. The bodies had often been wrapped for burial in finely-woven textiles.

Chinchorro mummies

The Chinchorro mummies are the oldest intentionally prepared mummified bodies ever found. Beginning in 5th millennium BC and continuing for an estimated 3,500 years, all human burials within the Chinchorro culture were prepared for mummification. The bodies were carefully prepared, beginning with removal of the internal organs and skin, before being left in the hot, dry climate of the Atacama Desert, which aided in desiccation. A large number of Chinchorro mummies were also prepared by skilled artisans to be preserved in a more artistic fashion, though the purpose of this practice is widely debated.

Inca mummies

Several naturally-preserved, unintentional mummies dating from the Incan period (1438–1532 AD) have been found in the colder regions of Argentina, Chile, and Peru. These are collectively known as "ice mummies". The first Incan ice mummy was discovered in 1954 atop El Plomo Peak in Chile, after an eruption of the nearby volcano Sabancaya melted away ice that covered the body. The Mummy of El Plomo was a male child who was presumed to be wealthy due to his well-fed bodily characteristics. He was considered to be the most well-preserved ice mummy in the world until the discovery of Mummy Juanita in 1995.

Mummy Juanita was discovered near the summit of Ampato in the Peruvian section of the Andes mountains by archaeologist Johan Reinhard. Her body had been so thoroughly frozen that it had not been desiccated; much of her skin, muscle tissue, and internal organs retained their original structure. She is believed to be a ritual sacrifice, due to the close proximity of her body to the Incan capital of Cusco, as well as the fact she was wearing highly intricate clothing to indicate her special social status. Several Incan ceremonial artifacts and temporary shelters uncovered in the surrounding area seem to support this theory.

More evidence that the Inca left sacrificial victims to die in the elements, and later be unintentionally preserved, came in 1999 with the discovery of the Llullaillaco mummies on the border of Argentina and Chile. The three mummies are children, two girls and one boy, who are thought to be sacrifices associated with the ancient ritual of qhapaq hucha. Recent biochemical analysis of the mummies has revealed that the victims had consumed increasing quantities of alcohol and coca, possibly in the form of chicha, in the months leading up to sacrifice. The dominant theory for the drugging reasons that, alongside ritual uses, the substances probably made the children more docile. Chewed coca leaves found inside the eldest child's mouth upon her discovery in 1999 supports this theory.

The bodies of Inca emperors and wives were mummified after death. In 1533, the Spanish conquistadors of the Inca Empire viewed the mummies in the Inca capital of Cuzco. The mummies were displayed, often in lifelike positions, in the palaces of the deceased emperors and had a retinue of servants to care for them. The Spanish were impressed with the quality of the mummification which involved removal of the organs, embalming, and freeze-drying.

The population revered the mummies of the Inca emperors. This reverence seemed idolatry to the Roman Catholic Spanish and in 1550 they confiscated the mummies. The mummies were taken to Lima where they were displayed in the San Andres Hospital. The mummies deteriorated in the humid climate of Lima and eventually they were either buried or destroyed by the Spanish.

An attempt to find the mummies of the Inca emperors beneath the San Andres hospital in 2001 was unsuccessful. The archaeologists found a crypt, but it was empty. Possibly the mummies had been removed when the building was repaired after an earthquake.

Self-mummification

Monks whose bodies remain incorrupt without any traces of deliberate mummification are venerated by some Buddhists who believe they successfully were able to mortify their flesh to death. Self-mummification was practiced until the late 1800s in Japan and has been outlawed since the early 1900s.

Many Mahayana Buddhist monks were reported to know their time of death and left their last testaments and their students accordingly buried them sitting in lotus position, put into a vessel with drying agents (such as wood, paper, or lime) and surrounded by bricks, to be exhumed later, usually after three years. The preserved bodies would then be decorated with paint and adorned with gold.

Bodies purported to be those of self-mummified monks are exhibited in several Japanese shrines, and it has been claimed that the monks, prior to their death, stuck to a sparse diet made up of salt, nuts, seeds, roots, pine bark, and urushi tea.

Modern mummies

Jeremy Bentham

In the 1830s, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, left instructions to be followed upon his death which led to the creation of a sort of modern-day mummy. He asked that his body be displayed to illustrate how the "horror at dissection originates in ignorance"; once so displayed and lectured about, he asked that his body parts be preserved, including his skeleton (minus his skull, which despite being mis-preserved, was displayed beneath his feet until theft required it to be stored elsewhere), which were to be dressed in the clothes he usually wore and "seated in a Chair usually occupied by me when living in the attitude in which I am sitting when engaged in thought". His body, outfitted with a wax head created because of problems preparing it as Bentham requested, is on open display in the University College London.

Vladimir Lenin

During the early 20th century, the Russian movement of Cosmism, as represented by Nikolai Fyodorovich Fyodorov, envisioned scientific resurrection of dead people. The idea was so popular that, after Vladimir Lenin's death, Leonid Krasin and Alexander Bogdanov suggested to cryonically preserve his body and brain in order to revive him in the future. Necessary equipment was purchased abroad, but for a variety of reasons the plan was not realized. Instead his body was embalmed and placed on permanent exhibition in the Lenin Mausoleum in Moscow, where it is displayed to this day. The mausoleum itself was modeled by Alexey Shchusev on the Pyramid of Djoser and the Tomb of Cyrus.

Gottfried Knoche

In late 19th-century Venezuela, a German-born doctor named Gottfried Knoche conducted experiments in mummification at his laboratory in the forest near La Guaira. He developed an embalming fluid (based on an aluminum chloride compound) that mummified corpses without having to remove the internal organs. The formula for his fluid was never revealed and has not been discovered. Most of the several dozen mummies created with the fluid (including himself and his immediate family) have been lost or were severely damaged by vandals and looters.

Summum

In 1975, an esoteric organization by the name of Summum introduced "Modern Mummification", a service that utilizes modern techniques along with aspects of ancient methods of mummification. The first person to formally undergo Summum's process of modern mummification was the founder of Summum, Summum Bonum Amen Ra, who died in January 2008. Summum is currently considered to be the only "commercial mummification business" in the world.

Alan Billis

In 2010, a team led by forensic archaeologist Stephen Buckley mummified Alan Billis using techniques based on 19 years of research of 18th-dynasty Egyptian mummification. The process was filmed for television, for the documentary Mummifying Alan: Egypt's Last Secret. Billis made the decision to allow his body to be mummified after being diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2009. His body currently resides at London's Gordon Museum.

Amélie of Leuchtenberg

Amélie of Leuchtenberg (1812–1873) was Empress of Brazil as the wife of Emperor Pedro I (also King of Portugal as Pedro IV). Between February and September 2012, researchers at the University of São Paulo in Brazil exhumed her remains, as well as those of her husband and his first wife, Maria Leopoldina. They were surprised to find that the body of Amélie had been mummified. Skin, hair and internal organs were preserved. Examinations at the Hospital das Clínicas found an incision in the empress' jugular vein. Aromatics such as camphor and myrrh were injected into the incision during the embalming process. "It certainly helped to nullify the decomposition," said Brazilian forensic archaeologist Valdirene Ambiel, responsible for the research. She added that another contributing factor was the casket, saying it was so hermetically sealed that there were no micro-organisms in it. Before the reburial, scientists reembalmed Amélie's mummified body using a method similar to the first one.

The remains of Amélie, Pedro I, and Maria Leopoldina are interred in the Monument to the Independence of Brazil in São Paulo.

Plastination

Plastination is a technique used in anatomy to conserve bodies or body parts. The water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or decay, and even retain most microscopic properties of the original sample.

The technique was invented by Gunther von Hagens when working at the anatomical institute of the Heidelberg University in 1978. Von Hagens has patented the technique in several countries and is heavily involved in its promotion, especially as the creator and director of the Body Worlds traveling exhibitions, exhibiting plastinated human bodies internationally. He also founded and directs the Institute for Plastination in Heidelberg.

More than 40 institutions worldwide have facilities for plastination, mainly for medical research and study, and most affiliated to the International Society for Plastination.

Treatment of ancient mummies in modern times

In the Middle Ages, based on a mistranslation from the Arabic term for bitumen, it was thought that mummies possessed healing properties. As a result, it became common practice to grind Egyptian mummies into a powder to be sold and used as medicine. When actual mummies became unavailable, the sun-desiccated corpses of criminals, slaves and suicidal people were substituted by mendacious merchants. Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle recommended them for healing bruises and preventing bleeding. The trade in mummies seems to have been frowned upon by Turkish authorities who ruled Egypt – several Egyptians were imprisoned for boiling mummies to make oil in 1424. However, mummies were in high demand in Europe and it was possible to buy them for the right amount of money. John Snaderson, an English tradesman who visited Egypt in the 16th century shipped six hundred pounds of mummy back to England.

The practice developed into a wide-scale business that flourished until the late 16th century. Two centuries ago, mummies were still believed to have medicinal properties to stop bleeding, and were sold as pharmaceuticals in powdered form as in mellified man. Artists also made use of Egyptian mummies; a brownish pigment known as mummy brown, based on mummia (sometimes called alternatively caput mortuum, Latin for death's head), which was originally obtained by grinding human and animal Egyptian mummies. It was most popular in the 17th century, but was discontinued in the early 19th century when its composition became generally known to artists who replaced the said pigment by a totally different blend -but keeping the original name, mummia or mummy brown-yielding a similar tint and based on ground minerals (oxides and fired earths) and or blends of powdered gums and oleoresins (such as myrrh and frankincense) as well as ground bitumen. These blends appeared on the market as forgeries of powdered mummy pigment but were ultimately considered as acceptable replacements, once antique mummies were no longer permitted to be destroyed. Many thousands of mummified cats were also sent from Egypt to England to be processed for use in fertilizer.

During the 19th century, following the discovery of the first tombs and artifacts in Egypt, egyptology was a huge fad in Europe, especially in Victorian England. European aristocrats would occasionally entertain themselves by purchasing mummies, having them unwrapped, and holding observation sessions. The pioneer of this kind of entertainment in Britain was Thomas Pettigrew known as "Mummy" Pettigrew due to his work. Such unrolling sessions destroyed hundreds of mummies, because the exposure to the air caused them to disintegrate.

The use of mummies as fuel for locomotives was documented by Mark Twain (likely as a joke or humor), but the truth of the story remains debatable. During the American Civil War, mummy-wrapping linens were said to have been used to manufacture paper. Evidence for the reality of these claims is still equivocal. Researcher Ben Radford reports that, in her book The Mummy Congress, Heather Pringle writes: "No mummy expert has ever been able to authenticate the story ... Twain seems to be the only published source – and a rather suspect one at that". Pringle also writes that there is no evidence for the "mummy paper" either. Radford also says that many journalists have not done a good job with their research, and while it is true that mummies were often not shown respect in the 1800s, there is no evidence for this rumor.

While mummies were used in medicine, some researchers have brought into question these other uses such as making paper and paint, fueling locomotives and fertilizing land.