An extrajudicial killing (also known as an extrajudicial execution or an extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whether lawfully or unlawfully, targeting specific people for death, which in authoritarian regimes often involves political, trade union, dissident, religious and social figures. The term is typically used in situations that imply the human rights of the victims have been violated; deaths caused by police actions or legitimate warfighting are generally not included, even though military and police forces are often used for killings seen by critics as illegitimate. The label "extrajudicial killing" has also been applied to organized, lethal enforcement of extralegal social norms by non-government actors, including lynchings and honor killings.

United Nations

Morris Tidball-Binz was appointed the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions on 1 April 2021 by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Human rights groups

Many human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, are campaigning against extrajudicial punishment.

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative measures the right to freedom from extrajudicial execution for countries around the world, using a survey of in-country human rights experts.

International law

Law of war

Article 3(d) of the First Geneva Convention explicitly prohibits carrying out executions without passing a prior judgement by a competent and regularly constituted court with all commonly recognized judicial guarantees for everyone taking part in the trial.

By country

Africa

Burundi

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Burundi.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Egypt

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Egypt. Egypt recorded and reported more than a dozen unlawful extrajudicial killings of apparent ‘terrorists’ in the country by the NSA officers and the Interior Ministry police in September 2021. A 101-page report detailed the ‘armed militants’ being killed in shootouts despite not posing any threat to the security forces or nations of the country while being killed, which in many cases were already in custody. Statements by the family and relatives of those killed claimed that the victims were not involved in any armed or violent activities.

Eritrea

The 2019 Universal Periodic Review of the United Nations Human Rights Council found that in 2016, Eritrean authorities committed extrajudicial killings, in the context of a "persistent, widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population" since 1991, including "the crimes of enslavement, imprisonment, enforced disappearance, torture, other inhumane acts, persecution, rape and murder".

Ethiopia

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Ethiopia.

Ivory Coast

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Ivory Coast.

Kenya

Extrajudicial executions are common in informal settlements in Kenya. Killings are also common in Northern Kenya under the guise of counter-terrorism operations.

Libya

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Libya.

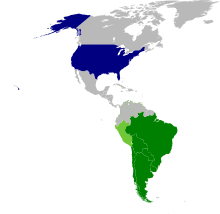

Americas

Argentina

Argentina's National Reorganization Process military dictatorship during the 1976–1983 period used extrajudicial killings systematically as way of crushing the opposition in the so-called "Dirty War" or what is known in Spanish as La Guerra Sucia. During this violent period, it is estimated that the military regime killed between eleven thousand and fifteen thousand people and most of the victims were known or suspected to be opponents of the regime. These included intellectuals, labor leaders, human rights workers, priests, nuns, reporters, politicians, and artists as well as their relatives. Authorities Half of the number of extrajudicial killings were reportedly carried out by the murder squad that operated from a detention center in Buenos Aires called Escuela Mecanica de la Armada. The dirty wars in Argentina sometimes triggered even more violent conflicts since the killings and crackdowns precipitated responses from insurgents.

Brazil

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Brazil. Senator Flávio Bolsonaro, son of President Jair Bolsonaro, was accused of having ties to death squads.

Chile

When General Augusto Pinochet assumed power in the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, he immediately ordered the purges, torture, and deaths of more than 3,000 supporters of the previous democratic socialist government without trial. During his regime, which lasted from 1973 to 1989, elements of the Chilean Armed Forces and police continued committing extrajudicial killings. These included Manuel Contreras, the former head of Chile's National Intelligence Directorate (DINA), which served as Pinochet's secret police. He was behind numerous assassinations and human rights abuses such as the 1974 abduction and forced disappearance of Socialist Party of Chile leader Victor Olea Alegria. Some of the killings were also coordinated with other right-wing dictatorships in the Southern Cone in the so-called Operation Condor. There were reports of United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) involvement, particularly within its activities in Central and South America that promoted anti-Communist coups. While CIA's complicity was not proven, American dollars supported the regimes that carried out extrajudicial killings such as the Pinochet administration. CIA, for instance, helped create DINA and the agency admitted that Contreras was one of its assets.

Colombia

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Colombia.

An investigation of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace found that from 2002 to 2008, 6402 civilians were killed by the Government of Colombia, falsely claimed to be FARC rebels by the Military Forces of Colombia.

El Salvador

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in El Salvador. During the Salvadoran Civil War, death squads achieved notoriety when far-right vigilantes assassinated Archbishop Óscar Romero for his social activism in March 1980. In December 1980, four Americans—three nuns and a lay worker—were raped and murdered by a military unit later found to have been acting on specific orders. Death squads were instrumental in killing hundreds of peasants and activists, including such notable priests as Rutilio Grande. Because the death squads involved were found to have been soldiers of the Salvadoran Armed Forces, which was receiving U.S. funding and training from American advisors during the Carter administration, these events prompted outrage in the U.S. and led to a temporary cutoff in military aid from the Reagan administration, although death squad activity stretched well into the Reagan years (1981–1989) as well.

Honduras

Honduras also had death squads active through the 1980s, the most notorious of which was Battalion 316. Hundreds of people, including teachers, politicians and union bosses, were assassinated by government-backed forces. Battalion 316 received substantial support and training from the United States Central Intelligence Agency.

Jamaica

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Jamaica.

Mexico

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Mexico.

Suriname

On 7, 8, and 9 December 1982 fifteen prominent Surinamese men who had criticized Dési Bouterse's ruling military regime were murdered. This tragedy is known as the December murders. The acting commander of the army Dési Bouterse was sentenced 20 years in prison by the Surinamese court martial on the 29 November 2019.

United States

Due to the highly decentralized nature of policing in the United States, there are no official estimates of extrajudicial killings which are committed by law enforcement. According to research which was conducted by reporters at The Guardian, the number of killings which are committed by law enforcement in the United States is estimated to be around 1,000 per year. The same figure is used by international human rights groups such as Amnesty International. However, a 2021 study undertaken by researchers at the University of Washington and published in The Lancet suggests the total may be twice as high due to systemic underreporting by local police departments.

Based on a survey of human rights experts administered by the Human Rights Measurement Initiative, the U.S. scores a 4.1 on a scale of 0-10 on the right to freedom from extrajudicial execution.

Lynching

Lynching was the extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimised ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South because the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states.

Targeted killing

One issue regarding extrajudicial killing is the legal and moral status of targeted killing by unmanned aerial vehicles of the United States.

Section 3(a) of the United States Torture Victim Protection Act contains a definition of extrajudicial killing:

a deliberate killing not authorized by a previous judgment pronounced by a regular constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples. Such term, however, does not include any such killing that, under international law, is lawfully carried out under the authority of a foreign nation.

The legality of killings such as in the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011 and the death of Qasem Soleimani in 2020 have been brought into question. In that case, the US defended itself claiming the killing was not an assassination but an act of "National Self Defense". There had been just under 2,500 assassinations by targeted drone strike by 2015, and these too have questioned as being extrajudicial killings.

Concerns about targeted and sanctioned killings of non-Americans and American citizens in overseas counter-terrorism activities have been raised by lawyers, news firms and private citizens.

On September 30, 2011 a drone strike in Yemen killed American citizens Anwar al-Awlaki and Samir Khan. Both resided in Yemen at the time of their deaths. The executive order approving Al-Awlaki's death was issued by Barack Obama in 2010, and was challenged by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Center for Constitutional Rights in that year. The U.S. president issued an order, approved by the National Security Council, that Al-Awlaki's normal legal rights as a civilian should be suspended and his death should be imposed, as he was a threat to the United States. The reasons provided to the public for approval of the order were Al-Awlaki's links to the 2009 Fort Hood Massacre and the 2009 Christmas Day bomb plot, the attempted destruction of a Detroit-bound passenger-plane. The following month, al-Awlaki's son Abdulrahman al-Awlaki, an American citizen, was killed by another US drone strike and in January 2017 Nawar al-Awlaki, al-Awlaki's eight-year-old daughter, also an American citizen and half-sister of Abdulrahman, was shot to death during the raid on Yakla by American forces along with between 9 and 29 other civilians, up to 14 al-Qaeda fighters, and American Navy SEAL William Owens.

President Donald Trump

President Donald Trump continued the practice of extrajudicial killings of his predecessor. Those killed under this policy include:

- Qasem Soleimani, killed in Baghdad by a drone strike on 3 January 2020

The New York Times reported 13 November 2020 that Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah was assassinated 7 August 2020 on the streets of Tehran by Israeli operatives at the behest of the United States, according to four intelligence officials of the United States.

Comments on Michael Reinoehl's death

On September 3, 2020, a law enforcement officer in Lacey, Washington fatally shot Michael Forest Reinoehl during a shootout. Reinoehl initiated the shootout according to statements by officials. However, there were conflicting witness reports, most notably Nathaniel Dingess, who told The New York Times, that agents opened fire on Reinoehl while on the phone and eating candy without verbal warning. Dingess said that Reinoehl attempted to take cover by the side of a car before he was fatally shot and was only carrying a phone. Reinoehl was a self-described Antifa activist who was charged of second-degree murder by the Portland Police Bureau following the fatal shooting on August 29, 2020, of a Patriot Prayer supporter, Aaron J. Danielson, in Portland, Oregon. In a Fox News cable television interview September 12, 2020, hosted by Jeanine Pirro, President Trump commenting on Reinoehl's death said, "This guy [Reinoehl] was a violent criminal, and the U.S. Marshals killed him ... And I will tell you something – that's the way it has to be". At an October 15, 2020 rally in Greenville, North Carolina he further elaborated on his praise for the shooting. Trump said "they didn't want to arrest him", which Rolling Stone characterized as Trump describing the Reinoehl's death as an extrajudicial killing. although in a statement immediately after the death the United States Marshals Service had said that their task force was attempting to arrest Reinoehl.

President Joe Biden

President Joe Biden continued his predecessors' practice of extrajudicial killings. Those killed during his administration include:

- Ayman al-Zawhiri, killed in Kabul by a drone strike on 31 July 2022.

Venezuela

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Venezuela. According to Human Rights Watch almost 18,000 people have been killed by security forces in Venezuela since 2016 for "resistance to authority" and many of these killings may constitute extrajudicial execution. Amnesty International estimated that there were more than 8,200 extrajudicial killings in Venezuela from 2015 to 2017.

Ahead of a three-week session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, the OHCHR chief, Michelle Bachelet, visited Venezuela between 19 and 21 June 2019. Bachelet expressed her concerns for the "shockingly high" number of extrajudiciary killings and urged for the dissolution of the Special Action Forces (FAES). The report also details how the Venezuelan government has "aimed at neutralising, repressing and criminalising political opponents and people critical of the government" since 2016.

Asia

Afghanistan

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan officials presided over murders, abduction, and other abuses with the tacit backing of their government and its western allies, Human Rights Watch alleged in its report from March 2015.

Bangladesh

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Bangladesh.

The Bangladesh Police special security force Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) has long been known for extrajudicial killing. In a leaked WikiLeaks cable it was found that RAB was trained by the UK government. 16 RAB officials (sacked afterwards) including Lt Col (sacked) Tareque Sayeed, Major (sacked) Arif Hossain, and Lt Commander (sacked) Masud Rana were given death penalty for abduction, murder, concealing the bodies, conspiracy and destroying evidences in the Narayanganj Seven Murder case.

Beside this many alleged criminals were killed by Bangladesh police by the name of Crossfire. In 2018, many alleged drug dealers were killed in the name of "War on Drugs" in Bangladesh.

India

Hardeep Singh Nijjar was a political refugee from India living in Canada. He was murdered 18 June 2023. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau accused 18 September 2023 the Indian government publicly of complicity.

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in India. A form of extrajudicial killing is called police encounters. Such encounters are also being staged by military and other security forces. Extrajudicial killings are also common in Indian states especially in Uttar Pradesh where 73 people were killed from March 2017 to March 2019. Police Encounter on 6 December 2019, by the Telangana Police in the 2019 Hyderabad gang rape case killing the 4 accused is another form of extrajudicial killing.

Indonesia

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Indonesia.

Iran

In the 1953 Iranian coup d'état a regime was installed through the efforts of the American CIA and the British MI6 in which the Shah (hereditary monarch) Mohammad Reza Pahlavi used SAVAK death squads (also trained by the CIA) to imprison, torture and/or kill hundreds of dissidents. After the 1979 revolution death squads were used to an even greater extent by the new Islamic government. In 1983, the CIA gave the Supreme Leader of Iran—Ayatollah Khomeini—information on KGB agents in Iran. This information was probably used. The Iranian government later used death squads occasionally throughout the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s; however by the 2000s it seems to have almost entirely, if not completely, ceased using them.

The Dutch secretary of Foreign Affairs Stef Blok wrote Januari 2019 to the States General of the Netherlands that the intelligence service AIVD had strong indications that Iran is responsible for the murder of Mohammad Reza Kolahi Samadi in 2015 in Almere and of Ahmad Mola Nissi in 2017 in The Hague.

February 4, 2021 Iranian diplomat Asadollah Asadi and three other Iranian nationals were convicted in Antwerp for plotting to bomb a 2018 rally of National Council of Resistance of Iran in France.

Iraq

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Iraq.

Iraq was formed as a League of Nations mandate by the partition and domination of various tribal lands by the British Empire in the early 20th century, after the break-up of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I. The United Kingdom granted independence to the Kingdom of Iraq in 1932, on the urging of King Faisal, though the British Armed Forces retained military bases and transit rights. King Ghazi of Iraq ruled as a figurehead after King Faisal's death in 1933, while undermined by attempted military coups, until his death in 1939. The United Kingdom invaded Iraq in 1941 for fear that the government of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani might cut oil supplies to Western nations, and because of his links to the Axis powers. A military occupation followed the restoration of the Hashemite monarchy, and the occupation ended on October 26, 1947. Iraq was left with a national government led from Baghdad made up of Sunni ethnicity in key positions of power, ruling over an ad hoc nation splintered by tribal affiliations. This leadership used death squads and committed massacres in Iraq throughout the 20th century, culminating in the Ba'athist dictatorship of Saddam Hussein.

The country has since become increasingly partitioned following the Iraq War into three zones: a Kurdish ethnic zone to the north, a Sunni center and the Shia ethnic zone to the south. The secular Arab socialist Baathist leadership were replaced with a provisional and later constitutional government that included leadership roles for the Shia (Prime Minister) and Kurdish (President of the Republic) peoples of the nation. This paralleled the development of ethnic militias by the Shia, Sunni, and the Kurdish (Peshmerga).

There were death squads formed by members of every ethnicity. In the national capital of Baghdad some members of the now-Shia Iraqi security forces (and militia members posing as members of Iraqi Police or Iraqi Armed Forces) formed unofficial, unsanctioned, but long-tolerated death squads. They possibly had links to the Interior Ministry and were popularly known as the 'black crows'. These groups operated night or day. They usually arrested people, then either tortured or killed them.

The victims of these attacks were predominantly young males who had probably been suspected of being members of the Sunni insurgency. Agitators such as Abdul Razaq al-Na'as, Dr. Abdullateef al-Mayah, and Dr. Wissam Al-Hashimi have also been killed. These killings are not limited to men; women and children have also been arrested and/or killed. Some of these killings have also been part of simple robberies or other criminal activities.

A feature in a May 2005 issue of the magazine of The New York Times claimed that the Multi-National Force – Iraq had modelled the "Wolf Brigade", the Iraqi interior ministry police commandos, on the death squads used in the 1980s to crush the left-wing insurgency in El Salvador.

Western news organizations such as Time and People disassembled this by focusing on aspects such as probable militia membership, religious ethnicity, as well as uniforms worn by these squads rather than stating the United States-backed Iraqi government had death squads active in the Iraqi capital of Baghdad.

Israel

In a report from October 2015, Amnesty International documented incidents that "appear to have been extrajudicial executions" against Palestinian civilians. Several of those incidents occurred after Palestinians attempted to attack Israelis or Israel Defense Forces soldiers. Even though the attackers did not pose a serious threat, they were shot without attempting to arrest the suspects before resorting to the use of lethal force. Medical attention for severely wounded Palestinians was in many cases delayed by Israeli forces.

The New York Times reported 13 November 2020 that Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah was assassinated 7 August 2020 on the streets of Tehran by Israeli operatives at the behest of the United States, according to four intelligence officials of the United States.

Iranian nuclear physicist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was killed 27 November 2020 on a rural road in Absard, a city near Tehran. One American official — along with two other intelligence officials — said that Israel was behind the attack on the scientist.

On 16 March 2023, the Israeli Army killed four Palestinian militants in Jenin. One motionless victim was shot in the head. According to The Guardian, the Israeli group of military veterans against the occupation, Breaking the Silence, called this an "extrajudicial execution".

Pakistan

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Pakistan. A form of extrajudicial killing called encounter killings by police is common in Pakistan. Case in point is Naqeebullah Mehsud and Sahiwal Killings. The Province of Balochistan has also seen a significant number of disappearances, many of which have been attributed to security forces by residents: anti-government Baloch nationalists claim thousands of cases and have stated a belief that most of these disappeared persons have been killed. Official numbers of disappeared persons have varied considerably, ranging between 55 and 1,100 victims. Human rights organizations have dubbed this practice as the "kill and dump policy".

Papua New Guinea

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Papua New Guinea.

Philippines

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Philippines.

Maguindanao massacre

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has called the massacre the single deadliest event for journalists in history. Even prior to this, the CPJ had labeled the Philippines the second most dangerous country for journalists, second only to Iraq.

War on drugs

Following the victory of Rodrigo Duterte in the 2016 Philippine presidential election, a campaign against illegal drugs has led to widespread extrajudicial killings. This follows the actions by then-Mayor Duterte to roam Davao in order to "encounter to kill".

The Philippine president has urged its citizens to kill suspected criminals and drug addicts, ordered the police to adopt a shoot-to-kill policy, has offered rewards for killing suspects, and has even admitted to personally killing suspected criminals.

The move has sparked widespread condemnation from international publications and magazines, prompting the Philippine government to issue statements denying the existence of state-sanctioned killings.

Though Duterte's controversial war on drugs was opposed by the United States under President Barack Obama, the European Union, and the United Nations, Duterte claims that he has received approving remarks from US President Donald Trump.

On September 26, 2016, Duterte issued guidelines that would enable the United Nations Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Killings to probe the rising death toll. On December 14, 2016, Duterte cancelled the planned visit of the Rapporteur who declined to accept government conditions that were not consistent with the code of conduct for special rapporteurs.

Saudi Arabia

The Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi was assassinated at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018.

Syria

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Syria.

Tajikistan

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Tajikistan.

Thailand

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Thailand. Reportedly thousands of extrajudicial killings occurred during the 2003 anti-drug effort of Thailand's prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

Rumors still persist that there is collusion between the government, rogue military officers, the radical right wing, and anti-drug death squads.

Both Muslim and Buddhist sectarian death squads still operate in the south of the country.

Turkey

Extrajudicial killings and death squads are common in Turkey. In 1990 Amnesty International published its first report on extrajudicial executions in Turkey. In the following years the problem became more serious. The Human Rights Foundation of Turkey determined the following figures on extrajudicial executions in Turkey for the years 1991 to 2001:

| 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 |

| 98 | 283 | 189 | 129 | 96 | 129 | 98 | 80 | 63 | 56 | 37 |

In 2001 the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Ms. Asma Jahangir, presented a report on a visit to Turkey. The report presented details of killings of prisoners (26 September 1999, 10 prisoners killed in a prison in Ankara; 19 December 2000, an operation in 20 prisons launched throughout Turkey resulted in the death of 30 inmates and two gendarmes).

For the years 2000–2008 the Human Rights Association (HRA) gives the following figures on doubtful deaths/deaths in custody/extra judicial execution/torture by paid village guards.

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| 173 | 55 | 40 | 44 | 47 | 89 | 130 | 66 | 65 |

In 2008 the human rights organization Mazlum Der counted 25 extrajudicial killings in Turkey.

Vietnam

Nguyễn Văn Lém (referred to as Captain Bay Lop) (died 1 February 1968 in Saigon) was a member of the Viet Cong who was summarily shot in Saigon during the Tet Offensive. The photograph of his death would become one of many anti-Vietnam War icons in the Western World.

Europe

Belarus

In 1999 Belarusian opposition leaders Yury Zacharanka and Viktar Hanchar together with his business associate Anatol Krasouski disappeared. Hanchar and Krasouski disappeared the same day of a broadcast on state television in which President Alexander Lukashenko ordered the chiefs of his security services to crack down on "opposition scum". Although the State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus (KGB) had them under constant surveillance, the official investigation announced that the case could not be solved. The disappearance of journalist Dzmitry Zavadski in 2000 has also yielded no results. Copies of a report by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which linked senior Belarusian officials to the cases of disappearances, were confiscated. Human Rights Watch claims that Zacharanka, Hanchar, Krasouski and Zavadski likely became victims of extrajudicial executions.

Russia

Extrajudicial killings have taken place in Russia. In the Russian Federation, a number of journalist murders were attributed to public administration figures, usually where the publications would reveal their involvement in large corruption scandals. It has been regarded that the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko was linked to Russian special forces. American and British intelligence agents have claimed that Russian assassins, some possibly at orders of the government, are behind at least fourteen targeted killings in the United Kingdom that police authorities have termed non-suspicious. The United Kingdom attributes the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in March 2018 to the Russian military-intelligence agency GRU. The German foreign minister Heiko Maas said there were "several indications" that Russia was behind the poisoning of Alexei Navalny.

Soviet Union

In Soviet Russia, since 1918 the secret police organization Cheka was authorized to execute counter-revolutionaries without trial. Hostages were also executed by Cheka during the Red Terror in 1918–1920. The successors of Cheka also had the authority for extrajudicial executions. In 1937–38 hundreds of thousands were executed extrajudicially during the Great Purge under the lists approved by NKVD troikas. In some cases, the Soviet special services did not arrest and then execute their victims but just secretly killed them without any arrest. For example, Solomon Mikhoels was murdered in 1948 and his body was run over to create the impression of a traffic accident. The Soviet special services also conducted extrajudicial killings abroad, most notably of Leon Trotsky in 1940 in Mexico, Stepan Bandera in 1959 in Germany, Georgi Markov in 1978 in London.

Spain

From 1983 until 1987, the Spanish government supported paramilitary squads, denominated GAL, to fight ETA, a Basque terrorist organization. A relevant example was the Lasa and Zabala case, in which José Antonio Lasa and José Ignacio Zabala were kidnapped, tortured and executed by police forces in 1983.

United Kingdom

During the Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland, British security forces and intelligence agents were accused of committing extrajudicial killings against suspected IRA members. Brian Nelson, an Ulster Defence Association member and secret British agent, was convicted in a court of sectarian murders.

Operation Kratos referred to tactics developed by London's Metropolitan Police for dealing with suspected suicide bombers, most notably firing shots to the head without warning. Little was revealed about these tactics until after the mistaken shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes on 22 July 2005.