In descending order of quantity, Old English literature consists of: sermons and saints' lives; biblical translations; translated Latin works of the early Church Fathers; chronicles and narrative history works; laws, wills and other legal works; practical works on grammar, medicine, and geography; and poetry. In all, there are over 400 surviving manuscripts from the period, of which about 189 are considered major. In addition, some Old English text survives on stone structures and ornate objects.

The poem Beowulf, which often begins the traditional canon of English literature, is the most famous work of Old English literature. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle has also proven significant for historical study, preserving a chronology of early English history.

In addition to Old English literature, Anglo-Latin works comprise the largest volume of literature from the Early Middle Ages in England.

Extant manuscripts

Over 400 manuscripts remain from the Anglo-Saxon period, with most written during the 9th to 11th centuries. There were considerable losses of manuscripts as a result of the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 16th century.

Old English manuscripts have been highly prized by collectors since the 16th century, both for their historic value and for their aesthetic beauty with their uniformly spaced letters and decorative elements.

Paleography and codicology

Manuscripts written in both Latin and the vernacular remain. It is believed that Irish missionaries are responsible for the scripts used in early Anglo-Saxon texts, which include the Insular half-uncial (important Latin texts) and Insular minuscule (both Latin and the vernacular). In the 10th century, the Caroline minuscule was adopted for Latin, however the Insular minuscule continued to be used for Old English texts. Thereafter, it was increasingly influenced by Caroline minuscule, while retaining certain distinctively Insular letter-forms.

Early English manuscripts often contain later annotations in the margins of the texts; it is a rarity to find a completely unannotated manuscript. These include corrections, alterations and expansions of the main text, as well as commentary upon it, and even unrelated texts. The majority of these annotations appear to date to the 13th century and later.

Scriptoria

Seven major scriptoria produced a good deal of Old English manuscripts: Winchester; Exeter; Worcester; Abingdon; Durham; and two Canterbury houses, Christ Church and St. Augustine's Abbey.

Dialects

Regional dialects include Northumbrian; Mercian; Kentish; and West Saxon, leading to the speculation that much of the poetry may have been translated into West Saxon at a later date. An example of the dominance of the West Saxon dialect is a pair of charters, from the Stowe and British Museum collections, which outline grants of land in Kent and Mercia, but are nonetheless written in the West Saxon dialect of the period.

Poetic codices

There are four major poetic manuscripts:

- The Junius manuscript, also known as the Cædmon manuscript, is an illustrated collection of poems on biblical narratives. It is held at the Bodleian Library, with the shelfmark MS. Junius 11.

- The Exeter Book is an anthology which brings together riddles and longer texts. It has been held at the Exeter Cathedral library since it was donated there in the 11th century by Bishop Leofric, and has the shelfmark Exeter Dean and Chapter Manuscript 3501.

- The Vercelli Book contains both poetry and prose; it is not known how it came to be in Vercelli.

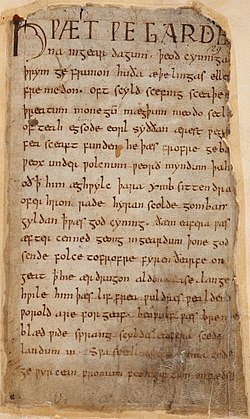

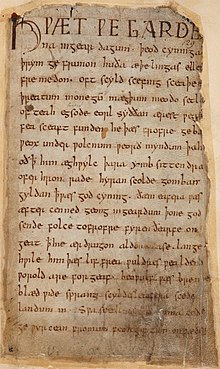

- The Beowulf Manuscript (British Library Cotton Vitellius A. xv), sometimes called the Nowell Codex, contains prose and poetry, typically dealing with monstrous themes, including Beowulf.

Poetry

Form and style

The most distinguishing feature of Old English poetry is its alliterative verse style.

The Anglo-Latin verse tradition in early medieval England was accompanied by discourses on Latin prosody, which were 'rules' or guidance for writers. The rules of Old English verse are understood only through modern analysis of the extant texts.

The first widely accepted theory was constructed by Eduard Sievers (1893), who distinguished five distinct alliterative patterns. His system of alliterative verse is based on accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation. It consists of five permutations on a base verse scheme; any one of the five types can be used in any verse. The system was inherited from and exists in one form or another in all of the older Germanic languages.

Alternative theories have been proposed, such as the theory of John C. Pope (1942), which uses musical notation to track the verse patterns. J. R. R. Tolkien describes and illustrates many of the features of Old English poetry in his 1940 essay "On Translating Beowulf".

Alliteration and assonance

Old English poetry alliterates, meaning that a sound (usually the initial stressed consonant sound) is repeated throughout a line. For instance, in the first line of Beowulf, "Hwaet! We Gar-Dena | in gear-dagum", (meaning "Listen! We of the Spear Danes in days of yore..."), the stressed sound in Gar-Dena and gear-dagum alliterate on the consonant "D".

Caesura

Old English poetry, like other Old Germanic alliterative verse, is also commonly marked by the caesura or pause. In addition to setting pace for the line, the caesura also grouped each line into two hemistichs.

Metaphor

Kennings are a key feature of Old English poetry. A kenning is an often formulaic metaphorical phrase that describes one thing in terms of another: for instance, in Beowulf, the sea is called the whale road. Another example of a kenning in The Wanderer is a reference to battle as a "storm of spears".

Old English poetry is marked by the comparative rarity of similes. Beowulf contains at best five similes, and these are of the short variety.

Variation

The Old English poet was particularly fond of describing the same person or object with varied phrases (often appositives) that indicated different qualities of that person or object. For instance, the Beowulf poet refers in three and a half lines to a Danish king as "lord of the Danes" (referring to the people in general), "king of the Scyldings" (the name of the specific Danish tribe), "giver of rings" (one of the king's functions is to distribute treasure), and "famous chief". Such variation, which the modern reader (who likes verbal precision) is not used to, is frequently a difficulty in producing a readable translation.

Litotes

Litotes is a form of dramatic understatement employed by the author for ironic effect.

Oral tradition

Even though all extant Old English poetry is written and literate, many scholars propose that Old English poetry was an oral craft that was performed by a scop and accompanied by a harp.

The hypotheses of Milman Parry and Albert Lord on the Homeric Question came to be applied (by Parry and Lord, but also by Francis Magoun) to verse written in Old English. That is, the theory proposes that certain features of at least some of the poetry may be explained by positing oral-formulaic composition. While Old English epic poetry may bear some resemblance to Ancient Greek epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, the question of if and how Anglo-Saxon poetry was passed down through an oral tradition remains a subject of debate, and the question for any particular poem unlikely to be answered with perfect certainty.

Parry and Lord had already demonstrated the density of metrical formulas in Ancient Greek, and observed the same feature in the Old English alliterative line:

Hroþgar maþelode helm Scildinga ("Hrothgar spoke, protector of the Scildings")

Beoƿulf maþelode bearn Ecgþeoƿes ("Beowulf spoke, son of Ecgtheow")

In addition to verbal formulas, many themes have been shown to appear among the various works of Anglo-Saxon literature. The theory suggests a reason for this: the poetry was composed of formulae and themes from a stock common to the poetic profession, as well as literary passages composed by individual artists in a more modern sense. Larry Benson introduced the concept of "written-formulaic" to describe the status of some Anglo-Saxon poetry which, while demonstrably written, contains evidence of oral influences, including heavy reliance on formulas and themes. Frequent oral-formulaic themes in Old English poetry include "Beasts of Battle" and the "Cliff of Death". The former, for example, is characterised by the mention of ravens, eagles, and wolves preceding particularly violent depictions of battle. Among the most thoroughly documented themes is "The Hero on the Beach". D. K. Crowne first proposed this theme, defined by four characteristics:

- A Hero on the Beach.

- Accompanying "Retainers".

- A Flashing Light.

- The Completion or Initiation of a Journey.

One example Crowne cites in his article is that which concludes Beowulf's fight with the monsters during his swimming match with Breca:

| Modern English | West Saxon | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Those sinful creatures had no fill of rejoicing that they consumed me, assembled at feast at the sea bottom; rather, in the morning, wounded by blades they lay up on the shore, put to sleep by swords, so that never after did they hinder sailors in their course on the sea. The light came from the east, the bright beacon of God. |

|

Crowne drew on examples of the theme's appearance in twelve Old English texts, including one occurrence in Beowulf. It was also observed in other works of Germanic origin, Middle English poetry, and even an Icelandic prose saga. John Richardson held that the schema was so general as to apply to virtually any character at some point in the narrative, and thought it an instance of the "threshold" feature of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey monomyth. J.A. Dane, in an article (characterised by Foley as "polemics without rigour") claimed that the appearance of the theme in Ancient Greek poetry, a tradition without known connection to the Germanic, invalidated the notion of "an autonomous theme in the baggage of an oral poet." Foley's response was that Dane misunderstood the nature of oral tradition, and that in fact the appearance of the theme in other cultures showed that it was a traditional form.

Poets

Most Old English poems are recorded without authors, and very few names are known with any certainty; the primary three are Cædmon, Aldhelm, and Cynewulf.

Bede

Bede is often thought to be the poet of a five-line poem entitled Bede's Death Song, on account of its appearance in a letter on his death by Cuthbert. This poem exists in a Northumbrian and later version.

Cædmon

Cædmon is considered the first Old English poet whose work still survives. He is a legendary figure, as described in Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. According to Bede, Cædmon was first an illiterate herdsman. Following a vision of a messenger from God, Cædmon received the gift of poetry, and then lived as a monk under Abbess Hild at the abbey of Whitby in Northumbria in the 7th century. Bede's History claims to reproduce Cædmon's first poem, comprising nine lines. Referred to as Cædmon's Hymn, the poem is extant in Northumbrian, West-Saxon and Latin versions that appear in 19 surviving manuscripts:

| Modern English | West Saxon | Northumbrian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now we must praise the Guardian of heaven, The power and conception of the Lord, And all His works, as He, eternal Lord, Father of glory, started every wonder. First He created heaven as a roof, The holy Maker, for the sons of men. Then the eternal Keeper of mankind Furnished the earth below, the land, for men, Almighty God and everlasting Lord. |

|

|

Cynewulf

Cynewulf has proven to be a difficult figure to identify, but recent research suggests he was an Anglian poet from the early part of the 9th century. Four poems are attributed to him, signed with a runic acrostic at the end of each poem; these are The Fates of the Apostles and Elene (both found in the Vercelli Book), and Christ II and Juliana (both found in the Exeter Book).

Although William of Malmesbury claims that Aldhelm, bishop of Sherborne (d. 709), performed secular songs while accompanied by a harp, none of these Old English poems survives. Paul G. Remely has recently proposed that the Old English Exodus may have been the work of Aldhelm, or someone closely associated with him.

Alfred

Alfred is said to be the author of some of the metrical prefaces to the Old English translations of Gregory's Pastoral Care and Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy. Alfred is also thought to be the author of 50 metrical psalms, but whether the poems were written by him, under his direction or patronage, or as a general part in his reform efforts is unknown.

Poetic genres and themes

Heroic poetry

The Old English poetry which has received the most attention deals with what has been termed the Germanic heroic past. Scholars suggest that Old English heroic poetry was handed down orally from generation to generation. As Christianity began to appear, re-tellers often recast the tales of Christianity into the older heroic stories.

The longest at 3,182 lines, and the most important, is Beowulf, which appears in the damaged Nowell Codex. Beowulf relates the exploits of the hero Beowulf, King of the Weder-Geats or Angles, around the middle of the 5th century. The author is unknown, and no mention of Britain occurs. Scholars are divided over the date of the present text, with hypotheses ranging from the 8th to the 11th centuries. It has achieved much acclaim as well as sustained academic and artistic interest.

Other heroic poems besides Beowulf exist. Two have survived in fragments: The Fight at Finnsburh, controversially interpreted by many to be a retelling of one of the battle scenes in Beowulf, and Waldere, a version of the events of the life of Walter of Aquitaine. Two other poems mention heroic figures: Widsith is believed to be very old in parts, dating back to events in the 4th century concerning Eormanric and the Goths, and contains a catalogue of names and places associated with valiant deeds. Deor is a lyric, in the style of Consolation of Philosophy, applying examples of famous heroes, including Weland and Eormanric, to the narrator's own case.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle contains various heroic poems inserted throughout. The earliest from 937 is called The Battle of Brunanburh, which celebrates the victory of King Athelstan over the Scots and Norse. There are five shorter poems: capture of the Five Boroughs (942); coronation of King Edgar (973); death of King Edgar (975); death of Alfred the son of King Æthelred (1036); and death of King Edward the Confessor (1065).

The 325 line poem The Battle of Maldon celebrates Earl Byrhtnoth and his men who fell in battle against the Vikings in 991. It is considered one of the finest, but both the beginning and end are missing and the only manuscript was destroyed in a fire in 1731. A well-known speech is near the end of the poem:

| Modern English | West Saxon | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thought shall be the harder, the heart the keener, courage the greater, as our strength lessens. Here lies our leader in the dust, all cut down; always may he mourn who now thinks to turn away from this warplay. I am old, I will not go away, but I plan to lie down by the side of my lord, by the man so dearly loved. |

|

Elegiac poetry

Related to the heroic tales are a number of short poems from the Exeter Book which have come to be described as "elegies" or "wisdom poetry". They are lyrical and Boethian in their description of the up and down fortunes of life. Gloomy in mood is The Ruin, which tells of the decay of a once glorious city of Roman Britain (cities in Britain fell into decline after the Romans departed in the early 5th century, as the early Celtic Britons continued to live their rural life), and The Wanderer, in which an older man talks about an attack that happened in his youth, when his close friends and kin were all killed; memories of the slaughter have remained with him all his life. He questions the wisdom of the impetuous decision to engage a possibly superior fighting force: the wise man engages in warfare to preserve civil society, and must not rush into battle but should seek out allies when the odds may be against him. This poet finds little glory in bravery for bravery's sake. The Seafarer is the story of a sombre exile from home on the sea, from which the only hope of redemption is the joy of heaven. Other wisdom poems include Wulf and Eadwacer, The Wife's Lament, and The Husband's Message. Alfred the Great wrote a wisdom poem over the course of his reign based loosely on the neoplatonic philosophy of Boethius called the Lays of Boethius.

Translations of classical and Latin poetry

Several Old English poems are adaptations of late classical philosophical texts. The longest is a 10th-century translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy contained in the Cotton manuscript Otho A.vi. Another is The Phoenix in the Exeter Book, an allegorisation of the De ave phoenice by Lactantius.

Other short poems derive from the Latin bestiary tradition. These include The Panther, The Whale and The Partridge.

Riddles

The most famous Old English riddles are found in the Exeter Book. They are part of a wider Anglo-Saxon literary tradition of riddling, which includes riddles written in Latin. Riddles are both comical and obscene.

The riddles of the Exeter Book are unnumbered and without titles in the manuscript. For this reason, scholars propose different interpretations of how many riddles there are, with some agreeing 94 riddles, and others proposing closer to 100 riddles in the book. Most scholars believe that the Exeter Book was compiled by a single scribe; however, the works were almost certainly originally composed by poets.

A riddle in Old English, written using runic script, features on the Franks Casket. One possible solution for the riddle is 'whale', evoking the whale-bone from which the casket made.

Saints' lives in verse

The Vercelli Book and Exeter Book contain four long narrative poems of saints' lives, or hagiographies. In Vercelli are Andreas and Elene and in Exeter are Guthlac and Juliana.

Andreas is 1,722 lines long and is the closest of the surviving Old English poems to Beowulf in style and tone. It is the story of Saint Andrew and his journey to rescue Saint Matthew from the Mermedonians. Elene is the story of Saint Helena (mother of Constantine) and her discovery of the True Cross. The cult of the True Cross was popular in Anglo-Saxon England and this poem was instrumental in promoting it.

Guthlac consists of two poems about the English 7th century Saint Guthlac. Juliana describes the life of Saint Juliana, including a discussion with the devil during her imprisonment.

Poetic Biblical paraphrases

There are a number of partial Old English Bible translations and paraphrases surviving. The Junius manuscript contains three paraphrases of Old Testament texts. These were re-wordings of Biblical passages in Old English, not exact translations, but paraphrasing, sometimes into beautiful poetry in its own right. The first and longest is of Genesis (originally presented as one work in the Junius manuscript but now thought to consist of two separate poems, A and B), the second is of Exodus and the third is Daniel. Contained in Daniel are two lyrics, Song of the Three Children and Song of Azarias, the latter also appearing in the Exeter Book after Guthlac. The fourth and last poem, Christ and Satan, which is contained in the second part of the Junius manuscript, does not paraphrase any particular biblical book, but retells a number of episodes from both the Old and New Testament.

The Nowell Codex contains a Biblical poetic paraphrase, which appears right after Beowulf, called Judith, a retelling of the story of Judith. This is not to be confused with Ælfric's homily Judith, which retells the same Biblical story in alliterative prose.

Old English translations of Psalms 51-150 have been preserved, following a prose version of the first 50 Psalms. There are verse translations of the Gloria in Excelsis, the Lord's Prayer, and the Apostles' Creed, as well as some hymns and proverbs.

Original Christian poems

In addition to Biblical paraphrases are a number of original religious poems, mostly lyrical (non-narrative).

The Exeter Book contains a series of poems entitled Christ, sectioned into Christ I, Christ II and Christ III.

Considered one of the most beautiful of all Old English poems is Dream of the Rood, contained in the Vercelli Book. The presence of a portion of the poem (in Northumbrian dialect) carved in runes on an 8th century stone cross found in Ruthwell, Dumfriesshire, verifies the age of at least this portion of the poem. The Dream of the Rood is a dream vision in which the personified cross tells the story of the crucifixion. Christ appears as a young hero-king, confident of victory, while the cross itself feels all the physical pain of the crucifixion, as well as the pain of being forced to kill the young lord.

| Modern English | West Saxon | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full many a dire experience on that hill. I saw the God of hosts stretched grimly out. Darkness covered the Ruler's corpse with clouds, A shadow passed across his shining beauty, under the dark sky. All creation wept, bewailed the King's death. Christ was on the cross. |

|

The dreamer resolves to trust in the cross, and the dream ends with a vision of heaven.

There are a number of religious debate poems. The longest is Christ and Satan in the Junius manuscript, which deals with the conflict between Christ and Satan during the forty days in the desert. Another debate poem is Solomon and Saturn, surviving in a number of textual fragments, Saturn is portrayed as a magician debating with the wise king Solomon.

Other poems

Other poetic forms exist in Old English including short verses, gnomes, and mnemonic poems for remembering long lists of names.

There are short verses found in the margins of manuscripts which offer practical advice, such as remedies against the loss of cattle or how to deal with a delayed birth, often grouped as charms. The longest is called Nine Herbs Charm and is probably of pagan origin. Other similar short verses, or charms, include For a Swarm of Bees, Against a Dwarf, Against a Stabbing Pain, and Against a Wen.

There are a group of mnemonic poems designed to help memorise lists and sequences of names and to keep objects in order. These poems are named Menologium, The Fates of the Apostles, The Rune Poem, The Seasons for Fasting, and the Instructions for Christians.

Prose

The amount of surviving Old English prose is much greater than the amount of poetry. Of the surviving prose, the majority consists of the homilies, saints' lives and biblical translations from Latin. The division of early medieval written prose works into categories of "Christian" and "secular", as below, is for convenience's sake only, for literacy in Anglo-Saxon England was largely the province of monks, nuns, and ecclesiastics (or of those laypeople to whom they had taught the skills of reading and writing Latin and/or Old English). Old English prose first appears in the 9th century, and continues to be recorded through the 12th century as the last generation of scribes, trained as boys in the standardised West Saxon before the Conquest, died as old men.

Christian prose

The most widely known secular author of Old English was King Alfred the Great (849–899), who translated several books, many of them religious, from Latin into Old English. Alfred, wanting to restore English culture, lamented the poor state of Latin education:

So general was [educational] decay in England there were very few on this side of the Humber who could...translate a letter from Latin into English; and I believe that there were not many beyond the Humber

— Pastoral Care, introduction, translated by Kevin Crossley-Holland

Alfred proposed that students be educated in Old English, and those who excelled should go on to learn Latin. Alfred's cultural program aimed to translate "certain books [...] necessary for all men to know" from Latin to Old English. These included: Gregory the Great's Cura Pastoralis, a manual for priests on how to conduct their duties, which became the Hierdeboc ('Shepherd-book') in Old English; Boethius' De Consolatione philosophiae (the Froforboc or 'book of consolation'); and the Soliloquia of Saint Augustine (known in Old English as the Blostman or 'blooms'). In the process, some original content was interweaved through the translations.

Other important Old English translations include: Orosius' Historiae Adversus Paganos, a companion piece for St. Augustine's The City of God; the Dialogues of Gregory the Great; and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Ælfric of Eynsham, who wrote in the late 10th and early 11th centuries, is believed to have been a pupil of Æthelwold. He was the greatest and most prolific writer of sermons, which were copied and adapted for use well into the 13th century. In the translation of the first six books of the Bible (Old English Hexateuch), portions have been assigned to Ælfric on stylistic grounds. He included some lives of the saints in the Catholic Homilies, as well as a cycle of saints' lives to be used in sermons. Ælfric also wrote an Old English work on time-reckoning, and pastoral letters.

In the same category as Ælfric, and a contemporary, was Wulfstan II, archbishop of York. His sermons were highly stylistic. His best known work is Sermo Lupi ad Anglos in which he blames the sins of the English for the Viking invasions. He wrote a number of clerical legal texts: Institutes of Polity and Canons of Edgar.

One of the earliest Old English texts in prose is the Martyrology, information about saints and martyrs according to their anniversaries and feasts in the church calendar. It has survived in six fragments. It is believed to have been written in the 9th century by an anonymous Mercian author.

The oldest collections of church sermons is the Blickling homilies, found in a 10th-century manuscript.

There are a number of saint's lives prose works: beyond those written by Ælfric are the prose life of Saint Guthlac (Vercelli Book), the life of Saint Margaret and the life of Saint Chad. There are four additional lives in the earliest manuscript of the Lives of Saints, the Julius manuscript: Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, Saint Mary of Egypt, Saint Eustace and Saint Euphrosyne.

There are six major manuscripts of the Wessex Gospels, dating from the 11th and 12th centuries. The most popular, Old English Gospel of Nicodemus, is treated in one manuscript as though it were a 5th gospel; other apocryphal gospels in translation include the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, Vindicta salvatoris, Vision of Saint Paul and the Apocalypse of Thomas.

Secular prose

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was probably started in the time of King Alfred the Great and continued for over 300 years as a historical record of Anglo-Saxon history.

A single example of a Classical romance has survived: a fragment of the story of Apollonius of Tyre was translated in the 11th century from the Gesta Romanorum.

A monk who was writing in Old English at the same time as Ælfric and Wulfstan was Byrhtferth of Ramsey, whose book Handboc was a study of mathematics and rhetoric. He also produced a work entitled Computus, which outlined the practical application of arithmetic to the calculation of calendar days and movable feasts, as well as tide tables.

Ælfric wrote two proto-scientific works, Hexameron and Interrogationes Sigewulfi, dealing with the stories of Creation. He also wrote a grammar and glossary of Latin in Old English, later used by students interested in learning Old French, as inferred from glosses in that language.

In the Nowell Codex is the text of The Wonders of the East which includes a remarkable map of the world, and other illustrations. Also contained in Nowell is Alexander's Letter to Aristotle. Because this is the same manuscript that contains Beowulf, some scholars speculate it may have been a collection of materials on exotic places and creatures.

There are a number of interesting medical works. There is a translation of Apuleius's Herbarium with striking illustrations, found together with Medicina de Quadrupedibus. A second collection of texts is Bald's Leechbook, a 10th-century book containing herbal and even some surgical cures. A third collection, known as the Lacnunga, includes many charms and incantations.

Legal texts are a large and important part of the overall Old English corpus. The Laws of Aethelberht I of Kent, written at the turn of the 7th century, are the earliest surviving English prose work. Other laws wills and charters were written over the following centuries. Towards the end of the 9th, Alfred had compiled the law codes of Aethelberht, Ine, and Offa in a text setting out his own laws, the Domboc. By the 12th century they had been arranged into two large collections (see Textus Roffensis). They include laws of the kings, beginning with those of Aethelbert of Kent and ending with those of Cnut, and texts dealing with specific cases and places in the country. An interesting example is Gerefa, which outlines the duties of a reeve on a large manor estate. There is also a large volume of legal documents related to religious houses. These include many kinds of texts: records of donations by nobles; wills; documents of emancipation; lists of books and relics; court cases; guild rules. All of these texts provide valuable insights into the social history of Anglo-Saxon times, but are also of literary value. For example, some of the court case narratives are interesting for their use of rhetoric.

Writing on objects

James Paz proposes reading objects which feature Old English poems or phrases as part of the literary output of the time, and as "speaking objects". These objects include the Ruthwell monument (which includes a poem similar to the Dream of the Rood preserved in the Vercelli Book), the Frank's Casket, the Alfred Jewel.

Semi-Saxon and post-conquest Old English

The Soul's Address to the Body (c. 1150–1175) found in Worcester Cathedral Library MS F. 174 contains only one word of possible Latinate origin, while also maintaining a corrupt alliterative meter and Old English grammar and syntax, albeit in a degenerative state (hence, early scholars of Old English termed this late form as "Semi-Saxon").

'The Grave' is a poem preserved in a 12th century manuscript, MS Bodleian 343, at fol. 170r: over time, scholars have called it "Anglo-Saxon", "Norman-Saxon", late Old English, and Middle English.

The Peterborough Chronicle can also be considered a late-period text, continuing into the 12th century.

Reception and scholarship

Later medieval glossing and translation

Old English literature did not disappear in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Many sermons and works continued to be read and used in part or whole up through the 14th century, and were further catalogued and organised. What might be termed the earliest scholarship on Old English literature was done by a 12th or early 13th-century scribe from Worcester known only as The Tremulous Hand – a sobriquet earned for a hand tremor causing characteristically messy handwriting. The Tremulous Hand is known for many Latin glosses of Old English texts, which represent the earliest attempt to translate the language in the post-Norman period. Perhaps his most well known scribal work is that of the Worcester Cathedral Library MS F. 174, which contains part of Ælfric's Grammar and Glossary and a short fragmentary poem often called St. Bede's Lament, in addition to the Body and Soul poem.

Antiquarianism and early scholarship

During the Reformation, when monastic libraries were dispersed, the manuscripts began to be collected by antiquarians and scholars. Some of the earliest collectors and scholars included Laurence Nowell, Matthew Parker, Robert Bruce Cotton and Humfrey Wanley.

Old English dictionaries and references were created from the 17th century. The first was William Somner's Dictionarium Saxonico-Latino-Anglicum (1659). Lexicographer Joseph Bosworth began a dictionary in the 19th century called An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, which was completed by Thomas Northcote Toller in 1898 and updated by Alistair Campbell in 1972.

19th, 20th, and 21st century scholarship

In the 19th and early 20th centuries the focus was on the Germanic and pagan roots that scholars thought they could detect in Old English literature. Because Old English was one of the first vernacular languages to be written down, 19th-century scholars searching for the roots of European "national culture" took special interest in studying what was then commonly referred to as 'Anglo-Saxon literature', and Old English became a regular part of university curriculum.

After World War II there was increasing interest in the manuscripts themselves, developing new palaeographic approaches from antiquarian approaches. Neil Ker, a paleographer, published the groundbreaking Catalogue of Manuscripts Containing Anglo-Saxon in 1957, and by 1980 nearly all Anglo-Saxon manuscript texts were available as facsimiles or editions.

On account of the work of Bernard F. Huppé, attention to the influence of Augustinian exegesis increased in scholarship.

J.R.R. Tolkien is often credited with creating a movement to look at Old English as a subject of literary theory in his seminal lecture "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics" (1936).

Since the 1970s, along with a focus upon paleography and the physical manuscripts themselves more generally, scholars continue to debate such issues as dating, place of origin, authorship, connections between Old English literary culture and global medieval literatures, and the valences of Old English poetry that may be revealed by contemporary theory: for instance, feminist, queer, critical race, and eco-critical theories.

Influence on modern English literature

Prose

Tolkien adapted the subject matter and terminology of heroic poetry for works like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and John Gardner wrote Grendel, which tells the story of Beowulf's opponent from his own perspective.

Poetry

Old English literature has had some influence on modern literature, and notable poets have translated and incorporated Old English poetry. Well-known early translations include Alfred, Lord Tennyson's translation of The Battle of Brunanburh, William Morris's translation of Beowulf, and Ezra Pound's translation of The Seafarer. The influence of the poetry can be seen in modern poets T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and W. H. Auden.

More recently other notable poets such as Paul Muldoon, Seamus Heaney, Denise Levertov and U. A. Fanthorpe have all shown an interest in Old English poetry. In 1987 Denise Levertov published a translation of Cædmon's Hymn under her title "Caedmon" in the collection Breathing the Water. This was followed by Seamus Heaney's version of the poem "Whitby-sur-Moyola" in his The Spirit Level (1996), Paul Muldoon's "Caedmona's Hymn" in his Moy Sand and Gravel (2002) and U. A. Fanthorpe's "Caedmon's Song" in her Queuing for the Sun (2003).

In 2000, Seamus Heaney published his translation of Beowulf. Heaney uses Irish diction across Beowulf to bring what he calls a "special body and force" to the poem, putting forward his own Ulster heritage, "in order to render [the poem] ever more 'willable forward/again and again and again.'"