| Sequoia sempervirens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Sequoia sempervirens along US 199 | |

| Binomial name | |

| Sequoia sempervirens | |

| |

| Natural range of California subfamily Sequoioideae

green - Sequoia sempervirens

red - Sequoiadendron giganteum

| |

Sequoia sempervirens (/səˈkwɔɪ.ə ˌsɛmpərˈvaɪrənz/) is the sole living species of the genus Sequoia in the cypress family Cupressaceae (formerly treated in Taxodiaceae). Common names include coast redwood, coastal redwood and California redwood. It is an evergreen, long-lived, monoecious tree living 1,200–2,200 years or more. This species includes the tallest living trees on Earth, reaching up to 115.9 m (380.1 ft) in height (without the roots) and up to 8.9 m (29 ft) in diameter at breast height. These trees are also among the longest-living trees on Earth. Before commercial logging and clearing began by the 1850s, this massive tree occurred naturally in an estimated 810,000 ha (2,000,000 acres) along much of coastal California (excluding southern California where rainfall is not sufficient) and the southwestern corner of coastal Oregon within the United States.

The name sequoia sometimes refers to the subfamily Sequoioideae, which includes S. sempervirens along with Sequoiadendron (giant sequoia) and Metasequoia (dawn redwood). Here, the term redwood on its own refers to the species covered in this article but not to the other two species.

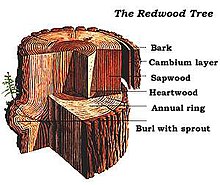

Description

The coast redwood normally reaches a height of 60 to 100 m (200 to 330 ft), but will be more than 110 m (360 ft) in extraordinary circumstances, with a trunk diameter of 9 m (30 ft). It has a conical crown, with horizontal to slightly drooping branches. The trunk is remarkably straight. The bark can be very thick, up to 35 cm (1.15 ft), and quite soft and fibrous, with a bright red-brown color when freshly exposed (hence the name redwood), weathering darker. The root system is composed of shallow, wide-spreading lateral roots.

The leaves are variable, being 15–25 mm (5⁄8–1 in) long and flat on young trees and shaded lower branches in older trees. The leaves are scalelike, 5–10 mm (1⁄4–3⁄8 in) long on shoots in full sun in the upper crown of older trees, with a full range of transition between the two extremes. They are dark green above and have two blue-white stomatal bands below. Leaf arrangement is spiral, but the larger shade leaves are twisted at the base to lie in a flat plane for maximum light capture.

The species is monoecious, with pollen and seed cones on the same plant. The seed cones are ovoid, 15–32 mm (9⁄16–1+1⁄4 in) long, with 15–25 spirally arranged scales; pollination is in late winter with maturation about 8–9 months after. Each cone scale bears three to seven seeds, each seed 3–4 mm (1⁄8–3⁄16 in) long and 0.5 mm (1⁄32 in) broad, with two wings 1 mm (1⁄16 in) wide. The seeds are released when the cone scales dry and open at maturity. The pollen cones are ovular and 4–6 mm (3⁄16–1⁄4 in) long.

Its genetic makeup is unusual among conifers, being a hexaploid (6n) and possibly allopolyploid (AAAABB). Both the mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes of the redwood are paternally inherited.

Taxonomy

Scottish botanist David Don described the redwood as Taxodium sempervirens, the "evergreen Taxodium", in his colleague Aylmer Bourke Lambert's 1824 work A description of the genus Pinus. Austrian botanist Stephan Endlicher erected the genus Sequoia in his 1847 work Synopsis coniferarum, giving the redwood its current binomial name of Sequoia sempervirens. It is unknown how Endlicher derived the name Sequoia. See Sequoia Etymology.

The redwood is one of three living species, each in its own genus, in the subfamily Sequoioideae. Molecular studies have shown that the three are each other's closest relatives, generally with the redwood and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) as each other's closest relatives.

However, Yang and colleagues in 2010 queried the polyploid state of the redwood and speculate that it may have arisen as an ancient hybrid between ancestors of the giant sequoia and dawn redwood (Metasequoia). Using two different single copy nuclear genes, LFY and NLY, to generate phylogenetic trees, they found that Sequoia was clustered with Metasequoia in the tree generated using the LFY gene, but with Sequoiadendron in the tree generated with the NLY gene. Further analysis strongly supported the hypothesis that Sequoia was the result of a hybridization event involving Metasequoia and Sequoiadendron. Thus, Yang and colleagues hypothesize that the inconsistent relationships among Metasequoia, Sequoia, and Sequoiadendron could be a sign of reticulate evolution (in which two species hybridize and give rise to a third) among the three genera. However, the long evolutionary history of the three genera (the earliest fossil remains being from the Jurassic) make resolving the specifics of when and how Sequoia originated once and for all a difficult matter—especially since it in part depends on an incomplete fossil record.

Names

The species name "sempervirens" means "evergreen", thought to be because of its previous placement in the same genus as Taxodium distichum (baldcypress) of the southeastern USA. Unlike coast redwood, baldcypress loses its leaves in winter. The common name "redwood", applied to both the coast redwood and the giant redwood, is a reference to the red heartwood of the trees. Common names that refer to Sequoia sempervirens alone include "California redwood", "coastal redwood", "coastal sequoia", and "coast redwood".

Distribution and habitat

Coast redwoods occupy a narrow strip of land approximately 750 km (470 mi) in length and 8–75 km (5–47 mi) in width along the Pacific coast of North America; the most southerly grove is in Monterey County, California, and the most northerly groves are in extreme southwestern Oregon. The prevailing elevation range is 30–750 m (100–2,460 ft) above sea level, occasionally down to 0 and up to about 900 m (3,000 ft). They usually grow in the mountains where precipitation from the incoming moisture off the ocean is greater. The tallest and oldest trees are found in deep valleys and gullies, where year-round streams can flow, and fog drip is regular. The terrain also made it harder for loggers to get to the trees and to get them out after felling. The trees above the fog layer, above about 700 m (2,300 ft), are shorter and smaller due to the drier, windier, and colder conditions. In addition, Douglas-fir, pine, and tanoak often crowd out redwoods at these elevations. Few redwoods grow close to the ocean, due to intense salt spray, sand, and wind. Coalescence of coastal fog accounts for a considerable part of the trees' water needs. Fog in the 21st century is, however, reduced from what it was in the prior century, which is a problem that may be compounded by climate change.

The northern boundary of its range is marked by two groves on mountain slopes along the north side of the Chetco River, which is on the western fringe of the Klamath Mountains, near the California–Oregon border. The northernmost grove is located within Alfred A. Loeb State Park and Siskiyou National Forest at the approximate coordinates 42°07'36"N 124°12'17"W. The southern boundary of its range is the Los Padres National Forest's Silver Peak Wilderness in the Santa Lucia Mountains of the Big Sur area of Monterey County, California. The southernmost grove is in the Southern Redwood Botanical Area, just north of the national forest's Salmon Creek trailhead and near the San Luis Obispo County line.

The largest and tallest populations are in California's Redwood National and State Parks (Del Norte and Humboldt counties) and Humboldt Redwoods State Park, with the overall majority located in the large Humboldt County.

The ancient range of the genus is considerably greater, with relatives of the coast redwood living in Europe and Asia prior to the Quaternary geologic period. In recent geologic time there have been considerable shifts in the coast redwood's range in North America. Coast redwood bark has been found in the La Brea Tar Pits, showing that 25,000–40,000 years before the present redwood trees grew as far south as the Los Angeles during the last ice age. The authors of a 2022 paper suggest, "Were it not for the remarkable ability to sprout after fire, many southern forests may have lost their Sequoia component long ago." As to previous redwood range to the north, an upright fossil stump of a coast redwood on a beach in central Oregon was documented 257 km north of the current range.

Assisted migration

The ability of Coast Redwood to live for more than a thousand years, along with its unusual capacity to resprout from its root crown when felled by natural or human causes, have earned this species the label of "carbon-sequestration champion." Its potential to contribute toward climate change mitigation, as well as its demonstrated ability to thrive in coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest, led to the formation of a citizen group in Seattle, Washington undertaking assisted migration of this species hundreds of miles north of its native range.

In contrast to cautionary statements made by forestry professionals assessing other tree species for assisted migration, the citizens involved with the group known as PropagationNation had met with little controversy until in 2023 a national news outlet published a lengthy article that cast a favorable light on their efforts. The New York Times Magazine wrote:

Not wanting to cause ecological problems by planting the trees across the Pacific Northwest, [Philip] Stielstra would eventually contact one of the foremost experts on the coast redwood, a botanist and forest ecologist named Stephen Sillett, at Cal Poly Humboldt, and ask if moving redwoods north was safe. Sillett thought planting redwoods around Seattle was a fantastic idea. ("It's not like it's going to escape and become a nuisance species," Sillett told me, before adding, "it just has so many benefits.") Another factor encouraged Stielstra too: Millions of years ago, redwoods — or their close relatives — grew across the Pacific Northwest. By moving them, Stielstra reasoned, he was helping the magnificent trees regain lost territory.

In December 2023, the Associated Press exclusively reported criticism from professionals in the region and nationally: While beginning to favor experiments in assisted population migration of more southerly genetics of the main native timber tree, Douglas-fir, professionals were united against large-scale plantings of California redwoods into the Pacific Northwest. The next month, January 2024, carried a regional news article that, once again, showed strong support as well as bold statements by the group's founder.

Even before the controversy developed in Washington state, professionals in Canada were documenting horticultural plantings of the California species already in place in southwestern British Columbia. In 2022 a Canadian Forestry Service publication used northward horticultural plantings, along with a review of research detailing redwood's paleobiogeography and current range conditions, as grounds for proposing that Canada's Vancouver Island already offered "narrow strips of optimal habitat" for extending the range of coast redwood. The authors point to a topographical "bottleneck" north of the California border that could have impeded northward migration during the Holocene. The bottleneck entails a lack of lowland passages through the Oregon Coast Range north of the Chetco River, coupled with the absence of coastal landscapes beyond storm salt-spray and tsunami inundation — for which this conifer species is highly intolerant.

Ecology

Fog and flood adaptations

The native area provides a unique environment with heavy seasonal rains up to 2,500 mm (100 in) annually. Cool coastal air and fog drip keep the forest consistently damp year round. Several factors, including the heavy rainfall, create a soil with fewer nutrients than the trees need, causing them to depend heavily on the entire biotic community of the forest, and making efficient recycling of dead trees especially important. This forest community includes coast Douglas-fir, Pacific madrone, tanoak, western hemlock, and other trees, along with a wide variety of ferns, mosses, mushrooms, and redwood sorrel. Redwood forests provide habitat for a variety of amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles. Old-growth redwood stands provide habitat for the federally threatened spotted owl and the California-endangered marbled murrelet.

The height of S. sempervirens is closely tied to fog availability; taller trees become less frequent as fog becomes less frequent. As S. sempervirens' height increases, transporting water via water potential to the leaves becomes increasingly difficult due to gravity. Despite the high rainfall that the region receives (up to 100 cm), the leaves in the upper canopy are perpetually stressed for water. This water stress is exacerbated by long droughts in the summer. Water stress is believed to cause the morphological changes in the leaves, stimulating reduced leaf length and increased leaf succulence. To supplement their water needs, redwoods use frequent summer fog events. Fog water is absorbed through multiple pathways. Leaves directly take in fog from the surrounding air through the epidermal tissue, bypassing the xylem. Coast redwoods also absorb water directly through their bark. The uptake of water through leaves and bark repairs and reduces the severity of xylem embolisms, which occur when cavitations form in the xylem preventing the transport of water and nutrients. Fog may also collect on redwood leaves, drip to the forest floor, and be absorbed by the tree's roots. This fog drip may form 30% of the total water used by a tree in a year.

Redwoods often grow in flood-prone areas. Sediment deposits can form impermeable barriers that suffocate tree roots, and unstable soil in flooded areas often causes trees to lean to one side, increasing the risk of the wind toppling them. Immediately after a flood, redwoods grow their existing roots upwards into recently deposited sediment layers. A second root system then develops from adventitious buds on the newly buried trunk and the old root system dies. To counter lean, redwoods increase wood production on the vulnerable side, creating a supporting buttress. These adaptations create forests of almost exclusively redwood trees in flood-prone regions.

Pest and pathogen resistance

Coast redwoods are resistant to insect attack, fungal infection, and rot. These properties are conferred by concentrations of terpenoids and tannic acid in redwood leaves, roots, bark, and wood. Despite these chemical defenses, redwoods are still subject to insect infestations; none, however, are capable of killing a healthy tree. Bark is so thick on the bole that bark beetles cannot enter there. However, the canopy branches have thin bark (see photo at right) that native bark beetles are able to bore into for egg-laying and larval growth via tunnels.

Redwoods also face herbivory from mammals: black bears are reported to consume the inner bark of small redwoods, and black-tailed deer are known to eat redwood sprouts.

The oldest known coast redwood is about 2,200 years old; many others in the wild exceed 600 years. The numerous claims of older redwoods are incorrect. Because of their seemingly timeless lifespans, coast redwoods were deemed the "everlasting redwood" at the turn of the century; in Latin, sempervirens means "ever green" or "everlasting". Redwoods must endure various environmental disturbances to attain such great ages.

Fire adaptations

In response to forest fires, the trees have developed various adaptations. The thick, fibrous bark of coast redwoods is extremely fire-resistant; it grows to at least a foot thick and protects mature trees from fire damage. In addition, the redwoods contain little flammable pitch or resin. Fires, moreover, appear to actually benefit redwoods by causing substantial mortality in competing species, while having only minor effects on redwood. Burned areas are favorable to the successful germination of redwood seeds. A study published in 2010, the first to compare post-wildfire survival and regeneration of redwood and associated species, concluded that fires of all severity increase the relative abundance of redwood, and higher-severity fires provide the greatest benefit.

Self-pruning of its lower limbs as height is gained is a crucial adaptation to prevent ground fires from rising into the canopy, where branch bark is thin and leaves are vulnerable. In the millions of years that predated human evolution, this level of protection worked well against natural fires originating from lightning strikes.

When the first humans arrived in North America, redwoods thrived in regions where ground fires were intentionally set by indigenous populations on a seasonal basis. However, when peoples arrived from other continents in the past few centuries, indigenous fire practices were disallowed — even in the few places where the first peoples were permitted to continue living. Flammable brush and young trees thus accumulated.

Clearcut logging further hampered a return to a fire-resistant tall canopy. Governmental policies aimed at suppressing all natural and human-caused fires, even in parks and wilderness areas, amplified the accumulation of dense undergrowth and woody debris. Thus, even a naturally occurring ground fire could threaten to spread upwards and become a canopy fire spreading uncontrollably over a widening area.

Reproduction

Coast redwood reproduces both sexually by seed and asexually by sprouting of buds, layering, or lignotubers. Seed production begins at 10–15 years of age. Cones develop in the winter and mature by fall. In the early stages, the cones look like flowers, and are commonly called "flowers" by professional foresters, although this is not strictly correct. Coast redwoods produce many cones, with redwoods in new forests producing thousands per year. The cones themselves hold 90–150 seeds, but viability of seed is low, typically well below 15% with one estimate of average rates being 3 to 10 percent.The viability does increase with age, trees under 20 years old have a viability of about 1%, and do not generally reach the highest levels of viability until age 250. The rates decrease as the tree starts to get very old, with trees over 1,200 not reaching viability rates over 3%. The low viability may discourage seed predators, which do not want to waste time sorting chaff (empty seeds) from edible seeds. Successful germination often requires a fire or flood, reducing competition for seedlings. The winged seeds are small and light, weighing 3.3–5.0 mg (200–300 seeds/g; 5,600–8,500/ounce). The wings are not effective for wide dispersal, and seeds are dispersed by wind an average of only 60–120 m (200–390 ft) from the parent tree. Seedlings are susceptible to fungal infection and predation by banana slugs, brush rabbits, and nematodes. Most seedlings do not survive their first three years. However, those that become established grow rapidly, with young trees known to reach 20 m (66 ft) tall in 20 years. When canopy space is not available, small trees can remain suppressed for up to 400 years before accelerating their growth rate.

Coast redwoods can also reproduce asexually by layering or sprouting from the root crown, stump, or even fallen branches; if a tree falls over, it generates a row of new trees along the trunk, so many trees naturally grow in a straight line. Sprouts originate from dormant or adventitious buds at or under the surface of the bark. The dormant sprouts are stimulated when the main adult stem gets damaged or starts to die. Many sprouts spontaneously erupt and develop around the circumference of the tree trunk. Within a short period after sprouting, each sprout develops its own root system, with the dominant sprouts forming a ring of trees around the parent root crown or stump. This ring of trees is called a "fairy ring". Sprouts can achieve heights of 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) in a single growing season.

Redwoods may also reproduce using burls. A burl is a woody lignotuber that commonly appears on a redwood tree below the soil line, though usually within 3 m (10 ft) in depth from the soil surface. Coast redwoods develop burls as seedlings from the axils of their cotyledon, a trait that is extremely rare in conifers. When provoked by damage, dormant buds in the burls sprout new shoots and roots. Burls are also capable of sprouting into new trees when detached from the parent tree, though exactly how this happens is yet to be studied. Shoot clones commonly sprout from burls and are often turned into decorative hedges when found in suburbia.

Cultivation and uses

Coast redwood is one of the most valuable timber species in the lumbering industry. In California, 3,640 km2 (899,000 acres) of redwood forest are logged, virtually all of it second growth. Though many entities have existed in the cutting and management of redwoods, perhaps none has had a more storied role than the Pacific Lumber Company (1863–2008) of Humboldt County, California, where it owned and managed over 810 km2 (200,000 acres) of forests, primarily redwood. Coast redwood lumber is highly valued for its beauty, light weight, and resistance to decay. Its lack of resin makes it absorb water and resist fire.

P. H. Shaughnessy, Chief Engineer of the San Francisco Fire Department wrote:

In the recent great fire of San Francisco, that began April 18th, 1906, we succeeded in finally stopping it in nearly all directions where the unburned buildings were almost entirely of frame construction, and if the exterior finish of these buildings had not been of redwood lumber, I am satisfied that the area of the burned district would have been greatly extended.

Because of its impressive resistance to decay, redwood was extensively used for railroad ties and trestles throughout California. Many of the old ties have been recycled for use in gardens as borders, steps, house beams, etc. Redwood burls are used in the production of table tops, veneers, and turned goods.

The Yurok people, who occupied the region before European settlement, regularly burned ground cover in redwood forests to bolster tanoak populations from which they harvested acorns, to maintain forest openings, and to boost populations of useful plant species such as those for medicine or basketmaking.

Extensive logging of redwoods began in the early nineteenth century. The trees were felled by ax and saw onto beds of tree limbs and shrubs to cushion their fall. Stripped of their bark, the logs were transported to mills or waterways by oxen or horse. Loggers then burned the accumulated tree limbs, shrubs, and bark. The repeated fires favored secondary forests of primarily redwoods as redwood seedlings sprout readily in burned areas. The introduction of steam engines let crews drag logs through long skid trails to nearby railroads, furthering the reach of loggers beyond the land near rivers previously used to transport trees. This method of harvesting, however, disturbed large amounts of soil, producing secondary-growth forests of species other than redwood such as Douglas-fir, grand fir, and western hemlock. After World War II, trucks and tractors gradually replaced steam engines, giving rise to two harvesting approaches: clearcutting and selection harvesting. Clearcutting involved felling all the trees in a particular area. It was encouraged by tax laws that exempted all standing timber from taxation if 70% of trees in the area were harvested.[52] Selection logging, by contrast, called for the removal 25% to 50% of mature trees in the hopes that the remaining trees would allow for future growth and reseeding. This method, however, encouraged growth of other tree species, converting redwood forests into mixed forests of redwood, grand fir, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock. Moreover, the trees left standing were often felled by windthrow; that is, they were often blown over by the wind.

The coast redwood is naturalized in New Zealand, notably at Whakarewarewa Forest, Rotorua. Redwood has been grown in New Zealand plantations for more than 100 years, and those planted in New Zealand have higher growth rates than those in California, mainly because of even rainfall distribution through the year.

Other areas of successful cultivation outside of the native range include Great Britain, Italy, France, Haida Gwaii, middle elevations of Hawaii, Hogsback in South Africa, the Knysna Afromontane forests in the Western Cape, Grootvadersbosch Forest Reserve near Swellendam, South Africa and the Tokai Arboretum on the slopes of Table Mountain above Cape Town, a small area in central Mexico (Jilotepec), and the southeastern United States from eastern Texas to Maryland. It also does well in the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia), far north of its northernmost native range in southwestern Oregon. Coast redwood trees were used in a display at Rockefeller Center and then given to Longhouse Reserve in East Hampton, Long Island, New York, and these have now been living there for over twenty years and have survived at 2 °F (−17 °C).

This fast-growing tree can be grown as an ornamental specimen in those large parks and gardens that can accommodate its massive size. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.

Statistics

Fairly solid evidence indicates that coast redwoods were the world's largest trees before logging, with numerous historical specimens reportedly over 122 m (400 ft). The theoretical maximum potential height of coast redwoods is thought to be limited to between 122 and 130 m (400 and 427 ft), as evapotranspiration is insufficient to transport water to leaves beyond this range. Further studies have indicated that this maximum requires fog, which is prevalent in these trees' natural environment.

A tree reportedly 114.3 m (375 ft) in length was felled in Sonoma County by the Murphy Brothers saw mill in the 1870s, another claimed to be 115.8 m (380 ft) and 7.9 m (26 ft) in diameter was cut down near Eureka in 1914, and the Lindsey Creek tree was documented to have a height of 120 m (390 ft) when it was uprooted and felled by a storm in 1905. A tree reportedly 129.2 m (424 ft) tall was felled in November 1886 by the Elk River Mill and Lumber Company in Humboldt County, yielding 79,736 marketable board feet from 21 cuts. In 1893, a Redwood cut at the Eel River, near Scotia, reportedly measured 130.1 m (427 ft) in length, and 23.5 m (77 ft) in girth. However, limited evidence corroborates these historical measurements.

Today, trees over 60 m (200 ft) are common, and many are over 90 m (300 ft). The current tallest tree is the Hyperion tree, measuring 115.61 m (379.3 ft). The tree was discovered in Redwood National Park during mid-2006 by Chris Atkins and Michael Taylor, and is thought to be the world's tallest living organism. The previous record holder was the Stratosphere Giant in Humboldt Redwoods State Park at 112.84 m (370.2 ft) (as measured in 2004). Until it fell in March 1991, the "Dyerville Giant" was the record holder. It, too, stood in Humboldt Redwoods State Park and was 113.4 m (372 ft) high and estimated to be 1,600 years old. This fallen giant has been preserved in the park.

The largest known living coast redwood is Grogan's Fault, discovered in 2014 by Chris Atkins and Mario Vaden in Redwood National Park, with a main trunk volume of at least 1,084.5 cubic meters (38,299 cu ft) Other high-volume coast redwoods include Iluvatar, with a main trunk volume of 1,033 m3 (36,470 cu ft),[71]: 160 and the Lost Monarch, with a main trunk volume of 988.7 m3 (34,914 cu ft).

Albino redwoods are mutants that cannot manufacture chlorophyll. About 230 examples (including growths and sprouts) are known to exist, reaching heights of up to 20 m (66 ft). These trees survive like parasites, obtaining food from green parent trees. While similar mutations occur sporadically in other conifers, no cases are known of such individuals surviving to maturity in any other conifer species. Recent research news reports that albino redwoods can store higher concentrations of toxic metals, going so far as comparing them to organs or "waste dumps".

List of tallest trees

Heights of the tallest coast redwoods are measured yearly by experts. Even with recent discoveries of tall coast redwoods above 100 m (330 ft), it is likely that no taller trees will be discovered.

| Rank | Name | Height | Diameter | Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meters | Feet | Meters | Feet | |||

| 1 | Hyperion | 115.85 | 380.1 | 4.84 | 15.9 | Redwood National Park |

| 2 | Helios | 114.58 | 375.9 | 4.96 | 16.3 | Redwood National Park |

| 3 | Icarus | 113.14 | 371.2 | 3.78 | 12.4 | Redwood National Park |

| 4 | Stratosphere Giant | 113.05 | 370.9 | 5.18 | 17.0 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 5 | National Geographic | 112.71 | 369.8 | 4.39 | 14.4 | Redwood National Park |

| 6 | Orion | 112.63 | 369.5 | 4.33 | 14.2 | Redwood National Park |

| 7 | Federation Giant | 112.62 | 369.5 | 4.54 | 14.9 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 8 | Paradox | 112.51 | 369.1 | 3.90 | 12.8 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

| 9 | Mendocino | 112.32 | 368.5 | 4.19 | 13.7 | Montgomery Woods State Natural Reserve |

| 10 | Millennium | 111.92 | 367.2 | 2.71 | 8.9 | Humboldt Redwoods State Park |

Diameter is measured at 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) above average ground level (at breast height). Details of the precise locations for most of the tallest trees were not announced to the general public for fear of causing damage to the trees and the surrounding habitat. The tallest coast redwood easily accessible to the public is the National Geographic Tree, immediately trailside in the Tall Trees Grove of Redwood National Park.

List of largest trees

The following list shows the largest S. sempervirens by volume known as of 2001.

Calculating the volume of a standing tree is the practical equivalent of calculating the volume of an irregular cone, and is subject to error for various reasons. This is partly due to technical difficulties in measurement, and variations in the shape of trees and their trunks. Measurements of trunk circumference are taken at only a few predetermined heights up the trunk, and assume that the trunk is circular in cross-section, and that taper between measurement points is even. Also, only the volume of the trunk (including the restored volume of basal fire scars) is taken into account, and not the volume of wood in the branches or roots. The volume measurements also do not take cavities into account. Most coast redwoods with volumes greater than 850 m3 (30,000 cu ft) represent ancient fusions of two or more separate trees, which makes determining whether a coast redwood has a single stem or multiple stems difficult. Starting in 2014, more record-breaking coast redwood trees were discovered. The largest disclosed was a massive redwood called Grogan's Fault/Spartan, which has been measured to have a volume of 38,300 cubic feet. In 2021 during a meeting presentation titled Redwoods 101 run by Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park, an even larger redwood was revealed, allegedly surpassed only by 3 giant sequoias in size. This tree is popularly known as 'Hail Storm', and has a volume of 44,750 cubic feet.

Details of the precise locations for most of the tallest trees were not announced to the general public for fear of causing damage to the trees and the surrounding habitat. The largest coast redwood easily accessible to the public is Iluvatar, which stands prominently about 5 meters (16 ft) to the southeast of the Foothill Trail of Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park.

Canopy Layers

Redwood canopy soil forms from leaf and organic material litter shedding from upper portions of the tree, accumulating and decomposing on larger branches. These clusters of soil require a lot of hydration, but they have an incredible amount of retention once saturated. Redwoods can send roots into these wet soils, providing a water source removed from the forest floor. This creates a unique ecosystem within old growth trees full of fungi, vascular plants, and small creatures. An example of a creature that lives there are the Clouded Salamanders that has been discovered up to 40 meters high. Evidence shows they breed and are born in the canopy soil of Redwood trees. Due to the sheer mass height of these trees and the canopy layer, it was almost never explored for the last century. Due to the mass of these trees and the amount of trees in the surrounding area different molds of moss form on these canopies that are called epiphytes. These epiphytes have different characteristics but all of said species are very adaptable to the tough treetop weather and characteristics. After hundreds of years these trees have been shaped into making it possible for these epiphytes to survive through the winter rain and the fall fog.