Recreated Gutenberg press at the International Printing Museum, Carson, California

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print

medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It

marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the

cloth, paper or other medium was brushed or rubbed repeatedly to achieve

the transfer of ink, and accelerated the process. Typically used for

texts, the invention and global spread of the printing press was one of the most influential events in the second millennium.

Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith

by profession, developed, circa 1439, a printing system by adapting

existing technologies to printing purposes, as well as making inventions

of his own. Printing in East Asia had been prevalent since the Tang dynasty, and in Europe, woodblock printing based on existing screw presses

was common by the 14th century. Gutenberg's most important innovation

was the development of hand-molded metal printing matrices, thus

producing a movable type-based printing press system. His newly devised hand mould made possible the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type

in large quantities. Movable type had been hitherto unknown in Europe.

In Europe, the two inventions, the hand mould and the printing press,

together drastically reduced the cost of printing books and other

documents, particularly in short print runs.

The printing press spread within several decades to over two hundred cities in a dozen European countries. By 1500, printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than twenty million volumes.

In the 16th century, with presses spreading further afield, their

output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies.

The operation of a press became synonymous with the enterprise of

printing, and lent its name to a new medium of expression and

communication, "the press".

In Renaissance Europe, the arrival of mechanical movable type printing introduced the era of mass communication,

which permanently altered the structure of society. The relatively

unrestricted circulation of information and (revolutionary) ideas

transcended borders, captured the masses in the Reformation and threatened the power of political and religious authorities. The sharp increase in literacy broke the monopoly of the literate elite on education and learning and bolstered the emerging middle class. Across Europe, the increasing cultural self-awareness of its peoples led to the rise of proto-nationalism, and accelerated by the development of European vernacular languages, to the detriment of Latin's status as lingua franca. In the 19th century, the replacement of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press by steam-powered rotary presses allowed printing on an industrial scale.

History

Economic conditions and intellectual climate

Medieval university class (1350s)

The rapid economic and socio-cultural development of late medieval society

in Europe created favorable intellectual and technological conditions

for Gutenberg's improved version of the printing press: the

entrepreneurial spirit of emerging capitalism

increasingly made its impact on medieval modes of production, fostering

economic thinking and improving the efficiency of traditional

work-processes. The sharp rise of medieval learning and literacy amongst the middle class led to an increased demand for books which the time-consuming hand-copying method fell far short of accommodating.

Technological factors

Technologies preceding the press that led to the press's invention

included: manufacturing of paper, development of ink, woodblock

printing, and distribution of eyeglasses.

At the same time, a number of medieval products and technological

processes had reached a level of maturity which allowed their potential

use for printing purposes. Gutenberg took up these far-flung strands,

combined them into one complete and functioning system, and perfected

the printing process through all its stages by adding a number of

inventions and innovations of his own:

Early modern wine press. Such screw presses were applied in Europe to a wide range of uses and provided Gutenberg with the model for his printing press.

The screw press

which allowed direct pressure to be applied on flat-plane was already

of great antiquity in Gutenberg's time and was used for a wide range of

tasks. Introduced in the 1st century AD by the Romans, it was commonly employed in agricultural production for pressing wine grapes and (olive) oil fruit, both of which formed an integral part of the mediterranean and medieval diet. The device was also used from very early on in urban contexts as a cloth press for printing patterns. Gutenberg may have also been inspired by the paper presses which had spread through the German lands since the late 14th century and which worked on the same mechanical principles.

Gutenberg adopted the basic design, thereby mechanizing the printing process.

Printing, however, put a demand on the machine quite different from

pressing. Gutenberg adapted the construction so that the pressing power

exerted by the platen

on the paper was now applied both evenly and with the required sudden

elasticity. To speed up the printing process, he introduced a movable

undertable with a plane surface on which the sheets could be swiftly

changed.

Movable type sorted in a letter case and loaded in a composing stick on top

The concept of movable type was not new in the 15th century; movable type printing had been invented in China during the Song dynasty, and was later used in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty, where metal movable-type printing technology was developed in 1234. In Europe, sporadic evidence that the typographical principle,

the idea of creating a text by reusing individual characters, was well

understood and employed in pre-Gutenberg Europe had been cropping up

since the 12th century and possibly before. The known examples range

from Germany (Prüfening inscription) to England (letter tiles) to Italy.

However, the various techniques employed (imprinting, punching and

assembling individual letters) did not have the refinement and

efficiency needed to become widely accepted.

Gutenberg greatly improved the process by treating typesetting and printing as two separate work steps. A goldsmith by profession, he created his type pieces from a lead-based alloy which suited printing purposes so well that it is still used today. The mass production of metal letters was achieved by his key invention of a special hand mould, the matrix. The Latin alphabet proved to be an enormous advantage in the process because, in contrast to logographic writing systems, it allowed the type-setter to represent any text with a theoretical minimum of only around two dozen different letters.

Another factor conducive to printing arose from the book existing in the format of the codex, which had originated in the Roman period.

Considered the most important advance in the history of the book prior

to printing itself, the codex had completely replaced the ancient scroll at the onset of the Middle Ages (500 AD).

The codex holds considerable practical advantages over the scroll

format; it is more convenient to read (by turning pages), is more

compact, less costly, and, in particular, unlike the scroll, both recto and verso could be used for writing − and printing.

A paper codex of the acclaimed 42-line Bible, Gutenberg's major work

A fourth development was the early success of medieval papermakers at mechanizing paper manufacture. The introduction of water-powered paper mills, the first certain evidence of which dates to 1282, allowed for a massive expansion of production and replaced the laborious handcraft characteristic of both Chinese and Muslim papermaking. Papermaking centres began to multiply in the late 13th century in Italy, reducing the price of paper to one sixth of parchment and then falling further; papermaking centers reached Germany a century later.

Despite this it appears that the final breakthrough of paper depended just as much on the rapid spread of movable-type printing. It is notable that codices of parchment, which in terms of quality is superior to any other writing material, still had a substantial share in Gutenberg's edition of the 42-line Bible.

After much experimentation, Gutenberg managed to overcome the

difficulties which traditional water-based inks caused by soaking the

paper, and found the formula for an oil-based ink suitable for

high-quality printing with metal type.

Function and approach

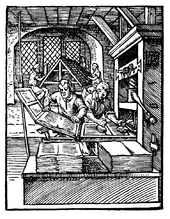

Early Press, etching from Early Typography by William Skeen

This woodcut

from 1568 shows the left printer removing a page from the press while

the one at right inks the text-blocks. Such a duo could reach 14,000

hand movements per working day, printing around 3,600 pages in the

process.

A

printing press, in its classical form, is a standing mechanism, ranging

from 5 to 7 feet (1.5 to 2.1 m) long, 3 feet (0.91 m) wide, and 7 feet

(2.1 m) tall. The small individual metal letters known as type would be

set up by a compositor into the desired lines of text. Several lines of

text would be arranged at once and were placed in a wooden frame known

as a galley. Once the correct number of pages were composed, the galleys

would be laid face up in a frame, also known as a forme.,

which itself is placed onto a flat stone, 'bed,' or 'coffin.' The text

is inked using two balls, pads mounted on handles. The balls were made

of dog skin leather, because it has no pores,

and stuffed with sheep's wool and were inked. This ink was then applied

to the text evenly. One damp piece of paper was then taken from a heap

of paper and placed on the tympan. The paper was damp as this lets the

type 'bite' into the paper better. Small pins hold the paper in place.

The paper is now held between a frisket and tympan (two frames covered with paper or parchment).

These are folded down, so that the paper lies on the surface of the inked type. The bed is rolled under the platen,

using a windlass mechanism. A small rotating handle is used called the

'rounce' to do this, and the impression is made with a screw that

transmits pressure through the platen. To turn the screw the long handle

attached to it is turned. This is known as the bar or 'Devil's Tail.'

In a well-set-up press, the springiness of the paper, frisket, and

tympan caused the bar to spring back and raise the platen, the windlass

turned again to move the bed back to its original position, the tympan

and frisket raised and opened, and the printed sheet removed. Such

presses were always worked by hand. After around 1800, iron presses were

developed, some of which could be operated by steam power.

The function of the press in the image on the left was described by William Skeen in 1872,

...this sketch represents a press in its completed form, with tympans attached to the end of the carriage, and with the frisket above the tympans. The tympans, inner and outer, are thin iron frames, one fitting into the other, on each of which is stretched a skin of parchment or a breadth of fine cloth. A woollen blanket or two with a few sheets of paper are placed between these, the whole thus forming a thin elastic pad, on which the sheet to be printed is laid. The frisket is a slender frame-work, covered with coarse paper, on which an impression is first taken; the whole of the printed part is then cut out, leaving apertures exactly corresponding with the pages of type on the carriage of the press. The frisket when folded on to the tympans, and both turned down over the forme of types and run in under the platten, preserves the sheet from contact with any thing but the inked surface of the types, when the pull, which brings down the screw and forces the platten to produce the impression, is made by the pressman who works the lever,—to whom is facetiously given the title of “the practitioner at the bar.”.

Gutenberg's press

Johannes Gutenberg's

work on the printing press began in approximately 1436 when he

partnered with Andreas Dritzehn—a man who had previously instructed in

gem-cutting—and Andreas Heilmann, owner of a paper mill. However, it was not until a 1439 lawsuit

against Gutenberg that an official record existed; witnesses' testimony

discussed Gutenberg's types, an inventory of metals (including lead),

and his type molds.

Having previously worked as a professional goldsmith, Gutenberg

made skillful use of the knowledge of metals he had learned as a

craftsman. He was the first to make type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony,

which was critical for producing durable type that produced

high-quality printed books and proved to be much better suited for

printing than all other known materials. To create these lead types,

Gutenberg used what is considered one of his most ingenious inventions, a special matrix enabling the quick and precise molding of new type blocks from a uniform template. His type case is estimated to have contained around 290 separate letter boxes, most of which were required for special characters, ligatures, punctuation marks, and so forth.

Gutenberg is also credited with the introduction of an oil-based ink which was more durable than the previously used water-based inks. As printing material he used both paper and vellum (high-quality parchment). In the Gutenberg Bible, Gutenberg made a trial of coloured printing for a few of the page headings, present only in some copies. A later work, the Mainz Psalter of 1453, presumably designed by Gutenberg but published under the imprint of his successors Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, had elaborate red and blue printed initials.

The Printing Revolution

The Printing Revolution occurred when the spread of the printing

press facilitated the wide circulation of information and ideas, acting

as an "agent of change" through the societies that it reached.

Mass production and spread of printed books

Spread of printing in the 15th century from Mainz, Germany

The European book output rose from a few million to around one billion copies within a span of less than four centuries.

The invention of mechanical movable type printing led to a huge

increase of printing activities across Europe within only a few decades.

From a single print shop in Mainz,

Germany, printing had spread to no less than around 270 cities in

Central, Western and Eastern Europe by the end of the 15th century.

As early as 1480, there were printers active in 110 different places in

Germany, Italy, France, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland,

England, Bohemia and Poland. From that time on, it is assumed that "the printed book was in universal use in Europe".

In Italy, a center of early printing, print shops had been

established in 77 cities and towns by 1500. At the end of the following

century, 151 locations in Italy had seen at one time printing

activities, with a total of nearly three thousand printers known to be

active. Despite this proliferation, printing centres soon emerged; thus,

one third of the Italian printers published in Venice.

By 1500, the printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than twenty million copies. In the following century, their output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies.

European printing presses of around 1600 were capable of producing about 1,500 impressions per workday. By comparison, book printing in East Asia did not use presses and was solely done by block printing.

Of Erasmus's work, at least 750,000 copies were sold during his lifetime alone (1469–1536). In the early days of the Reformation, the revolutionary potential of bulk printing took princes and papacy

alike by surprise. In the period from 1518 to 1524, the publication of

books in Germany alone skyrocketed sevenfold; between 1518 and 1520, Luther's tracts were distributed in 300,000 printed copies.

The rapidity of typographical text production, as well as the sharp fall in unit costs, led to the issuing of the first newspapers which opened up an entirely new field for conveying up-to-date information to the public.

Incunable are surviving pre-16th century print works which are collected by many of the libraries in Europe and North America.

Circulation of information and ideas

"Modern Book Printing" sculpture, commemorating Gutenberg's invention on the occasion of the 2006 World Cup in Germany

The printing press was also a factor in the establishment of a community of scientists

who could easily communicate their discoveries through the

establishment of widely disseminated scholarly journals, helping to

bring on the scientific revolution. Because of the printing press, authorship

became more meaningful and profitable. It was suddenly important who

had said or written what, and what the precise formulation and time of

composition was. This allowed the exact citing of references, producing

the rule, "One Author, one work (title), one piece of information"

(Giesecke, 1989; 325). Before, the author was less important, since a

copy of Aristotle

made in Paris would not be exactly identical to one made in Bologna.

For many works prior to the printing press, the name of the author has

been entirely lost.

Because the printing process ensured that the same information

fell on the same pages, page numbering, tables of contents, and indices

became common, though they previously had not been unknown. The process of reading also changed, gradually moving over several centuries from oral readings to silent, private reading.

Over the next 200 years, the wider availability of printed materials

led to a dramatic rise in the adult literacy rate throughout Europe.

The printing press was an important step towards the democratization of knowledge.

Within 50 or 60 years of the invention of the printing press, the

entire classical canon had been reprinted and widely promulgated

throughout Europe (Eisenstein, 1969; 52). More people had access to

knowledge both new and old, more people could discuss these works. Book

production became more commercialised, and the first copyright laws were passed.

On the other hand, the printing press was criticized for allowing the

dissemination of information which may have been incorrect.

A second outgrowth of this popularization of knowledge was the

decline of Latin as the language of most published works, to be replaced

by the vernacular language of each area, increasing the variety of

published works. The printed word also helped to unify and standardize

the spelling and syntax of these vernaculars, in effect 'decreasing'

their variability. This rise in importance of national languages as

opposed to pan-European Latin is cited as one of the causes of the rise of nationalism in Europe.

A third consequence of popularization of printing was on the

economy. The printing press was associated with higher levels of city

growth. The publication of trade related manuals and books teaching techniques like double-entry bookkeeping increased the reliability of trade and led to the decline of merchant guilds and the rise of individual traders.

Industrial printing presses

At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution,

the mechanics of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press were still

essentially unchanged, although new materials in its construction,

amongst other innovations, had gradually improved its printing

efficiency. By 1800, Lord Stanhope

had built a press completely from cast iron which reduced the force

required by 90%, while doubling the size of the printed area. With a capacity of 480 pages per hour, the Stanhope press doubled the output of the old style press. Nonetheless, the limitations inherent to the traditional method of printing became obvious.

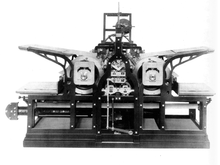

Koenig's 1814 steam-powered printing press

Two ideas altered the design of the printing press radically: First,

the use of steam power for running the machinery, and second the

replacement of the printing flatbed with the rotary motion of cylinders.

Both elements were for the first time successfully implemented by the

German printer Friedrich Koenig in a series of press designs devised between 1802 and 1818. Having moved to London in 1804, Koenig soon met Thomas Bensley and secured financial support for his project in 1807. Patented in 1810, Koenig had designed a steam press "much like a hand press connected to a steam engine." The first production trial of this model occurred in April 1811. He produced his machine with assistance from German engineer Andreas Friedrich Bauer.

Koenig and Bauer sold two of their first models to The Times in London

in 1814, capable of 1,100 impressions per hour. The first edition so

printed was on 28 November 1814. They went on to perfect the early model

so that it could print on both sides of a sheet at once. This began the

long process of making newspapers available to a mass audience (which in turn helped spread literacy), and from the 1820s changed the nature of book production, forcing a greater standardization in titles and other metadata. Their company Koenig & Bauer AG is still one of the world's largest manufacturers of printing presses today.

Rotary press

The steam powered rotary printing press, invented in 1843 in the United States by Richard M. Hoe,

allowed millions of copies of a page in a single day. Mass production

of printed works flourished after the transition to rolled paper, as

continuous feed allowed the presses to run at a much faster pace.

By the late 1930s or early 1940s, rotary presses had increased

substantially in efficiency: a model by Platen Printing Press was

capable of performing 2,500 to 3,000 impressions per hour.

Also, in the middle of the 19th century, there was a separate development of jobbing presses, small presses capable of printing small-format pieces such as billheads,

letterheads, business cards, and envelopes. Jobbing presses were

capable of quick set-up (average setup time for a small job was under 15

minutes) and quick production (even on treadle-powered jobbing presses

it was considered normal to get 1,000 impressions per hour [iph] with

one pressman, with speeds of 1,500 iph often attained on simple envelope

work). Job printing emerged as a reasonably cost-effective duplicating solution for commerce at this time.