The history of writing traces the development of expressing language by letters or other marks and also the studies and descriptions of these developments.

In the history of how writing systems have evolved in different human civilizations, more complete writing systems were preceded by proto-writing, systems of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols. True writing, in which the content of a linguistic utterance is encoded so that another reader can reconstruct, with a fair degree of accuracy, the exact utterance written down, is a later development. It is distinguished from proto-writing, which typically avoids encoding grammatical words and affixes, making it more difficult or impossible to reconstruct the exact meaning intended by the writer unless a great deal of context is already known in advance. One of the earliest forms of written expression is cuneiform.

Inventions of writing

Sumer, an ancient civilization of southern Mesopotamia, is believed to be the place where written language was first invented around 3100 BC

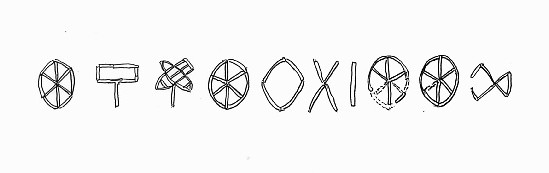

Limestone Kish tablet from Sumer with pictographic writing; may be the earliest known writing, 3500 BC. Ashmolean Museum

It is generally agreed that true writing of language (not only numbers, which goes back much further)

was independently conceived and developed in at least two ancient

civilizations and possibly more. The two places where it is most certain

that the concept of writing was both conceived and developed

independently are in ancient Sumer (in Mesopotamia), between 3400 and 3300 BC, and much later in Mesoamerica (by 300 BC) because no precursors have been found to either of these in their respective regions. Several Mesoamerican scripts are known, the oldest being from the Olmec or Zapotec of Mexico.

Independent writing systems also arose in Egypt around 3100 BC and in China around 1200 BC in Shang dynasty (商朝),

but historians debate whether these writing systems were developed

completely independently of Sumerian writing or whether either or both

were inspired by Sumerian writing via a process of cultural diffusion.

That is, it is possible that the concept of representing language by

using writing, though not necessarily the specifics of how such a system

worked, was passed on by traders or merchants traveling between the two

regions. (More recent examples of this include Pahawh Hmong and the Cherokee syllabary.)

Ancient Chinese characters

are considered by many to be an independent invention because there is

no evidence of contact between ancient China and the literate

civilizations of the Near East, and because of the distinct differences between the Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches to logography and phonetic representation. Egyptian script

is dissimilar from Mesopotamian cuneiform, but similarities in concepts

and in earliest attestation suggest that the idea of writing may have

come to Egypt from Mesopotamia. In 1999, Archaeology Magazine

reported that the earliest Egyptian glyphs date back to 3400 BC, which

"challenge the commonly held belief that early logographs, pictographic

symbols representing a specific place, object, or quantity, first

evolved into more complex phonetic symbols in Mesopotamia."

Similar debate surrounds the Indus script of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization, the Rongorongo script of Easter Island, and the Vinča symbols dated around 5,500 BCE. All are undeciphered, and so it is unknown if they represent true writing, proto-writing, or something else.

Writing systems

Symbolic communication systems are distinguished from writing systems

in that one must usually understand something of the associated spoken

language to comprehend the text. In contrast, symbolic systems, such as information signs, painting, maps, and mathematics,

often do not require prior knowledge of a spoken language. Every human

community possesses language, a feature regarded by many as an innate

and defining condition of mankind (see Origin of language). However the development of writing systems, and their partial supplantation of traditional oral

systems of communication, have been sporadic, uneven, and slow. Once

established, writing systems on the whole change more slowly than their

spoken counterparts and often preserve features and expressions that no

longer exist in the spoken language. The greatest benefit of writing is

that it provides the tool by which society can record information

consistently and in greater detail, something that could not be achieved

as well previously by spoken word. Writing allows societies to transmit

information and to share knowledge.

Recorded history

Scholars make a reasonable distinction between prehistory and history of early writing

but have disagreed concerning when prehistory becomes history and when

proto-writing became "true writing." The definition is largely

subjective. Writing, in its most general terms, is a method of recording information and is composed of graphemes, which may in turn be composed of glyphs.

The emergence of writing in a given area is usually followed by

several centuries of fragmentary inscriptions. Historians mark the

"historicity" of a culture by the presence of coherent texts in the

culture's writing system(s).

The invention of writing was not a one-time event but was a gradual process initiated by the appearance of symbols, possibly first for cultic purposes.

Developmental stages

A conventional "proto-writing to true writing" system follows a general series of developmental stages:

- Picture writing system: glyphs (simplified pictures)

directly represent objects and concepts. In connection with this, the

following substages may be distinguished:

- Mnemonic: glyphs primarily as a reminder.

- Pictographic: glyphs directly represent an object or a concept such as (A) chronological, (B) notices, (C) communications, (D) totems, titles, and names, (E) religious, (F) customs, (G) historical, and (H) biographical.

- Ideographic: graphemes are abstract symbols that directly represent an idea or concept.

- Transitional system: graphemes refer not only to the object or idea that it represents but to its name as well.

- Phonetic system: graphemes refer to sounds or spoken symbols,

and the form of the grapheme is not related to its meanings. This

resolves itself into the following substages:

- Verbal: grapheme (logogram) represents a whole word.

- Syllabic: grapheme represents a syllable.

- Alphabetic: grapheme represents an elementary sound.

The best known picture writing system of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols are:

- Jiahu symbols, carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, c. 6600 BC

- Vinča signs (Tărtăria tablets), c. 5300 BC

- Early Indus script, c. 3100 BC

In the Old World, true writing systems developed from neolithic writing in the Early Bronze Age (4th millennium BC). The Sumerian archaic (pre-cuneiform) writing and the Egyptian hieroglyphs

are generally considered the earliest true writing systems, both

emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from

3400–3100 BC, with earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BC.

Literature and writing

Literature and writing, though obviously connected, are not synonymous. The very first writings from ancient Sumer by any reasonable definition do not constitute literature. The same is true of some of the early Egyptian hieroglyphics and the thousands of ancient Chinese government records. The history of literature begins with the history of writing. Scholars have disagreed concerning when written record-keeping became more like literature

than anything else, but "literature" can have several meanings. The

term could be applied broadly to mean any symbolic record from images

and sculptures to letters. The oldest surviving literary texts date from

a full millennium after the invention of writing to the late 3rd

millennium BC. The earliest literary authors known by name are Ptahhotep (who wrote in Egyptian) and Enheduanna (who wrote in Sumerian), dating to around the 24th and 23rd

centuries BC, respectively. In the early literate societies, as much as

600 years passed from the first inscriptions to the first coherent

textual sources: i.e., from around 3100 to 2600 BC.

Locations and time frames

Proto-writing

Examples of the Jiahu symbols, markings found on tortoise shells, dated around 6000 BC. Most of the signs were separately inscribed on different shells.

The first writing systems of the Early Bronze Age were not a sudden invention. Rather, they were a development based on earlier traditions of symbol

systems that cannot be classified as proper writing but have many of

the characteristics of writing. These systems may be described as

"proto-writing." They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols to convey information, but it probably directly contained no natural language.

These systems emerged in the early Neolithic period, as early as the 7th millennium BC evidenced by the Jiahu symbols in China.

In 2003, tortoise shells were found in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu, Henan province, northern China, with radiocarbon dates from the 7th millennium BC. According to some archaeologists, the symbols carved on the shells had similarities to the late 2nd millennium BC oracle bone script.

Most archaeologists have dismissed this claim as insufficiently

substantiated, claiming that simple geometric designs, such as those

found on the Jiahu shells, cannot be linked to early writing. Other neolithic signs have also been found in China.

The Dispilio Tablet of the late 6th millennium is similar. The hieroglyphic scripts of the Ancient Near East

(Egyptian, Sumerian proto-Cuneiform, and Cretan) seamlessly emerge from

such symbol systems so that it is difficult to say at what exact time

writing developed from proto-writing. Further, very little is known

about the symbols' meanings.

The Vinča symbols, sometimes called the Danube script, Vinča signs, Vinča script, Vinča–Turdaș script, Old European script, etc., are a set of symbols found on Neolithic era (6th to 5th millennia BC) artifacts from the Vinča culture of Central Europe and Southeastern Europe.

Even after the Neolithic, several cultures went through an

intermediate stage of proto-writing before they used proper writing. The

"Slavic runes" from the 7th and 8th centuries AD, mentioned by a few medieval authors, may have been such a system. The quipu of the Incas

(15th century AD), sometimes called "talking knots," may have been of a

similar nature. Another example is the pictographs invented by Uyaquk before the development of the Yugtun syllabary (c. 1900).

Bronze Age writing

Writing emerged in many different cultures in the Bronze Age. Examples are the cuneiform writing of the Sumerians, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese logographs, Indus script, and the Olmec script of Mesoamerica. The Chinese script likely developed independently of the Middle Eastern scripts around 1600 BC. The pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems (including Olmec and Maya scripts) are also generally believed to have had independent origins.

It is thought that the first true alphabetic writing was developed around 2000 BC for Semitic workers in the Sinai by giving mostly Egyptian hieratic glyphs Semitic values (see History of the alphabet and Proto-Sinaitic alphabet). The Ge'ez

writing system of Ethiopia is considered Semitic. It is likely to be of

semi-independent origin, having roots in the Meroitic Sudanese ideogram

system. Most other alphabets in the world today either descended from this one innovation, many via the Phoenician alphabet, or were directly inspired by its design. In Italy, about 500 years passed from the early Old Italic alphabet to Plautus (750 to 250 BC), and in the case of the Germanic peoples, the corresponding time span is again similar, from the first Elder Futhark inscriptions to early texts like the Abrogans (c. AD 200 to 750).

Cuneiform script

Middle Babylonian legal tablet from Alalah in its envelope

The original Sumerian writing system derives from a system of clay tokens used to represent commodities. By the end of the 4th millennium BC,

this had evolved into a method of keeping accounts, using a

round-shaped stylus impressed into soft clay at different angles for

recording numbers. This was gradually augmented with pictographic

writing by using a sharp stylus to indicate what was being counted.

Round-stylus and sharp-stylus writing were gradually replaced around

2700–2500 BC by writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the term cuneiform), at first only for logograms,

but developed to include phonetic elements by the 29th century BC.

About 2600 BC, cuneiform began to represent syllables of the Sumerian language.

Finally, cuneiform writing became a general purpose writing system for

logograms, syllables, and numbers. From the 26th century BC, this script

was adapted to the Akkadian language, and from there to others, such as Hurrian and Hittite. Scripts similar in appearance to this writing system include those for Ugaritic and Old Persian.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Writing was very important in maintaining the Egyptian empire, and

literacy was concentrated among an educated elite of scribes. Only

people from certain backgrounds were allowed to train as scribes, in the

service of temple, royal (pharaonic), and military authorities.

Geoffrey Sampson believes that most scholars hold that Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into existence a little after Sumerian script, and ... probably [were] invented under the influence of the latter ..." This view, however, is strongly contested by other scholars. Dreyer's findings at Tomb UJ at Abydos in Upper Egypt

clearly show place names written in hieroglyphs (up to four in number)

recognizable as signs, which persisted and were employed during later

periods and which are written and read phonetically. The tomb is dated

to c. 3250 BC and demonstrates that such writing (on bone and ivory

labels) is a more advanced form of writing than was evident in Sumer at

that date. It is argued, therefore, that the Egyptian writing system,

which is in any case very different from the Mesopotamian, could not

have been the result of influence from a less-developed system existing

at that date in Sumer.

Elamite script

The undeciphered Proto-Elamite script emerges from as early as 3100 BC. It is believed to have evolved into Linear Elamite by the later 3rd millennium and then replaced by Elamite Cuneiform adopted from Akkadian.

Indus script

Ten Indus characters from the northern gate of Dholavira, India, dubbed the Dholavira Signboard.

The Middle Bronze Age Indus script, which dates back to the early Harappan phase of around 3000 BCE in the Indian subcontinent corresponding to northwestern India and what is now Pakistan, has not yet been deciphered.

It is unclear whether it should be considered an example of

proto-writing or whether it is actual writing of the

logographic-syllabic type of the other Bronze Age writing systems. Mortimer Wheeler recognizes the style of writing as boustrophedon, where "this stability suggests a precarious maturity."

Early Semitic alphabets

The first pure alphabets (properly, "abjads", mapping single symbols to single phonemes, but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol) emerged around 1800 BC in Ancient Egypt, as a representation of language developed by Semitic workers in Egypt, but by then alphabetic principles had a slight possibility of being inculcated into Egyptian hieroglyphs for upwards of a millennium.

These early abjads remained of marginal importance for several

centuries, and it is only towards the end of the Bronze Age that the Proto-Sinaitic script splits into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet (c. 1400 BC) Byblos syllabary and the South Arabian alphabet (c. 1200 BC). The Proto-Canaanite was probably somehow influenced by the undeciphered Byblos syllabary and, in turn, inspired the Ugaritic alphabet (c. 1300 BC).

Anatolian hieroglyphs

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous hieroglyphic script native to western Anatolia, used to record the Hieroglyphic Luwian language. It first appeared on Luwian royal seals from the 14th century BC.

Chinese writing

The earliest confirmed evidence of the Chinese script yet discovered

is the body of inscriptions on oracle bones from the late Shang dynasty

(c. 1200–1050 BC). From the Shang Dynasty, most of this writing has survived on bones or bronze implements (bronze script). Markings on turtle shells, or jiaguwen, have been carbon-dated to around 1500 BC. Historians have found that the type of medium chosen depended on the subject of the writing.

There have recently been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings dating back to c. 6000 BC, like Jiahu Script, Banpo Script, but whether or not the carvings are complex enough to qualify as writing is under debate. At Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region,

3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BC have been discovered,

featuring 8,453 individual characters, such as the sun, moon, stars,

gods, and scenes of hunting or grazing. These pictographs are reputed to

be similar to the earliest characters confirmed to be written Chinese.

If it is deemed to be a written language, writing in China will predate

Mesopotamian cuneiform, long acknowledged as the first appearance of

writing, by some 2,000 years; however it is more likely that the

inscriptions are rather a form of proto-writing, similar to the contemporary European Vinca script.

Cretan and Greek scripts

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Crete

(early-to-mid-2nd millennium BC, MM I to MM III, overlapping with

Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). Linear B, the writing system of

the Mycenaean Greeks,

has been deciphered while Linear A has yet to be deciphered. The

sequence and the geographical spread of the three overlapping, but

distinct, writing systems can be summarized as follows (note that the

beginning date refers to first attestations, the assumed origins of all

scripts lie further back in the past):

Mesoamerica

A stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing, the Cascajal Block,

was discovered in the Mexican state of Veracruz, and is an example of

the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere, preceding the oldest Zapotec writing dated to about 500 BC.

Of several pre-Columbian scripts in Mesoamerica, the one that appears to have been best developed, and has been fully deciphered, is the Maya script.

The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd

century BC, and writing was in continuous use until shortly after the

arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century AD. Maya

writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs: a

combination somewhat similar to modern Japanese writing.

Iron Age writing

Cippus Perusinus, Etruscan writing near Perugia, Italy, the precursor of the Latin alphabet

The sculpture depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Suddhodana the dream of Queen Maya, mother of Gautama Buddha.

Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is

possibly the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing

in India. From Nagarjunakonda, 2nd century CE.

The Phoenician alphabet is simply the Proto-Canaanite alphabet as it was continued into the Iron Age (conventionally taken from a cut-off date of 1050 BC). This alphabet gave rise to the Aramaic and Greek

alphabets. These in turn led to the writing systems used throughout

regions ranging from Western Asia to Africa and Europe. For its part the

Greek alphabet introduced for the first time explicit symbols for vowel

sounds. The Greek and Latin alphabets in the early centuries of the Common Era gave rise to several European scripts such as the Runes and the Gothic and Cyrillic alphabets while the Aramaic alphabet evolved into the Hebrew, Syriac and Arabic abjads and the South Arabian alphabet gave rise to the Ge'ez abugida. The Brahmic family of India is believed by some scholars to have derived from the Aramaic alphabet as well.

Writing in the Greco-Roman civilizations

Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens

The history of the Greek alphabet started when the Greeks borrowed the Phoenician alphabet and adapted it to their own language.

The letters of the Greek alphabet are more or less the same as those of

the Phoenician alphabet, and in modern times both alphabets are

arranged in the same order.

The adapter(s) of the Phoenician system added three letters to the end

of the series, called the "supplementals". Several varieties of the

Greek alphabet developed. One, known as Western Greek or Chalcidian, was used west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other variation, known as Eastern Greek, was used in present-day Turkey

and by the Athenians, and eventually the rest of the world that spoke

Greek adopted this variation. After first writing right to left, like

the Phoenicians, the Greeks eventually chose to write from left to

right.

Greek is in turn the source for all the modern scripts of Europe. The most widespread descendant of Greek is the Latin script, named for the Latins,

a central Italian people who came to dominate Europe with the rise of

Rome. The Romans learned writing in about the 5th century BC from the Etruscan civilization,

who used one of a number of Italic scripts derived from the western

Greeks. Due to the cultural dominance of the Roman state, the other

Italic scripts have not survived in any great quantity, and the Etruscan

language is mostly lost.

Writing during the Middle Ages

With the collapse of the Roman authority in Western Europe, the literary development became largely confined to the Eastern Roman Empire and the Persian Empire.

Latin, never one of the primary literary languages, rapidly declined in

importance (except within the Church of Rome). The primary literary

languages were Greek and Persian, though other languages such as Syriac and Coptic were important too.

The rise of Islam in the 7th century led to the rapid rise of Arabic

as a major literary language in the region. Arabic and Persian quickly

began to overshadow Greek's role as a language of scholarship. Arabic script was adopted as the primary script of the Persian language and the Turkish language. This script also heavily influenced the development of the cursive scripts of Greek, the Slavic languages, Latin, and other languages. The Arabic language also served to spread the Hindu–Arabic numeral system throughout Europe. By the beginning of the second millennium the city of Cordoba

in modern Spain, had become one of the foremost intellectual centers of

the world and contained the world's largest library at the time.

Its position as a crossroads between the Islamic and Western Christian

worlds helped fuel intellectual development and written communication

between both cultures.

Renaissance and the modern era

By the 14th century a rebirth, or renaissance,

had emerged in Western Europe, leading to a temporary revival of the

importance of Greek, and a slow revival of Latin as a significant

literary language. A similar though smaller emergence occurred in

Eastern Europe, especially in Russia. At the same time Arabic and

Persian began a slow decline in importance as the Islamic Golden Age

ended. The revival of literary development in Western Europe led to

many innovations in the Latin alphabet and the diversification of the

alphabet to codify the phonologies of the various languages.

The nature of writing has been constantly evolving, particularly

due to the development of new technologies over the centuries. The pen, the printing press, the computer and the mobile phone

are all technological developments which have altered what is written,

and the medium through which the written word is produced. Particularly

with the advent of digital technologies, namely the computer and the

mobile phone, characters can be formed by the press of a button, rather

than making a physical motion with the hand.

The nature of the written word has recently evolved to include an

informal, colloquial written style, in which an everyday conversation

can occur through writing rather than speaking. Written communication

can also be delivered with minimal time delay (e-mail, SMS), and in some cases, with an imperceptible time delay (instant messaging). Writing is a preservable means of communication.

Writing materials

There is no very definite statement as to the material which was in

most common use for the purposes of writing at the start of the early

writing systems.

In all ages it has been customary to engrave on stone or metal, or

other durable material, with the view of securing the permanency of the

record; and accordingly, in the very commencement of the national

history of Israel, it is read of the two tables of the law written in

stone, and of a subsequent writing of the law on stone. In the latter

case there is this peculiarity, that plaster (sic,

lime or gypsum) was used along with stone, a combination of materials

which is illustrated by comparison of the practice of the Egyptian

engravers, who, having first carefully smoothed the stone, filled up the

faulty places with gypsum or cement, in order to obtain a perfectly

uniform surface on which to execute their engravings. Metals, such as stamped coins, are mentioned as a material of writing; they include lead, brass, and gold. To the engraving of gems there is reference also, such as with seals or signets.

The common materials of writing were the tablet and the roll, the

former probably having a Chaldean origin, the latter an Egyptian. The

tablets of the Chaldeans are among the most remarkable of their remains.

There are small pieces of clay, somewhat rudely shaped into a form

resembling a pillow, and thickly inscribed with cuneiform characters.

Similar use has been seen in hollow cylinders, or prisms of six or

eight sides, formed of fine terra cotta, sometimes glazed, on which the

characters were traced with a small stylus, in some specimens so

minutely as to be capable of decipherment only with the aid of a

magnifying-glass.

In Egypt the principal writing material was of quite a different

sort. Wooden tablets are found pictured on the monuments; but the

material which was in common use, even from very ancient times, was the papyrus.

This reed, found chiefly in Lower Egypt, had various economic means for

writing, the pith was taken out, and divided by a pointed instrument

into the thin pieces of which it is composed; it was then flattened by

pressure, and the strips glued together, other strips being placed at

right angles to them, so that a roll of any length might be

manufactured. Writing seems to have become more widespread with the

invention of papyrus in Egypt. That this material was in use in Egypt

from a very early period is evidenced by still existing papyrus of the

earliest Theban dynasties. As the papyrus, being in great demand, and

exported to all parts of the world, became very costly, other materials

were often used instead of it, among which is mentioned leather, a few

leather mills of an early period having been found in the tombs. Parchment,

using sheepskins left after the wool was removed for cloth, was

sometimes cheaper than papyrus, which had to be imported outside Egypt.

With the invention of wood-pulp paper, the cost of writing material began a steady decline.