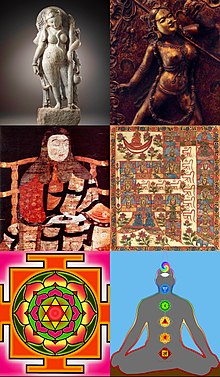

Kundalini chakra diagram

Kundalini in Hinduism refers to a form of primal energy (or shakti) said to be located at the base of the spine.

In Hindu tradition, Bhairavi is the goddess of Kundalini. Kundalini awakenings may happen through a variety of methods. Many systems of yoga focus on awakening Kundalini through: meditation; pranayama breathing; the practice of asana and chanting of mantras. Kundalini Yoga is influenced by Shaktism and Tantra schools of Hinduism. It derives its name through a focus on awakening kundalini energy through regular practice of Mantra, Tantra, Yantra, Yoga

or Meditation.

The Kundalini experience is frequently reported to be a distinct feeling of electric current running along the spine.

Etymology

The concept of Kundalini is mentioned in the Upanishads (9th century BCE – 3rd century BCE). The Sanskrit adjective kuṇḍalin

means "circular, annular". It is mentioned as a noun for "snake" (in

the sense "coiled", as in "forming ringlets") in the 12th-century Rajatarangini chronicle (I.2). Kuṇḍa (a noun meaning "bowl, water-pot" is found as the name of a Naga in Mahabharata 1.4828). The 8th-century Tantrasadbhava Tantra uses the term kundalī ("ring, bracelet; coil (of a rope)").

The use of kuṇḍalī as a name for Goddess Durga (a form of Shakti) appears often in Tantrism and Shaktism from as early as the 11th century in the Śaradatilaka. It was adopted as a technical term in Hatha yoga during the 15th century, and became widely used in the Yoga Upanishads by the 16th century. Eknath Easwaran

has paraphrased the term as "the coiled power", a force which

ordinarily rests at the base of the spine, described as being "coiled

there like a serpent".

Descriptions

When awakened, Kundalini is said to rise up from the muladhara chakra, through the central nadi (called sushumna) inside or alongside the spine reaching the top of the head. The progress of Kundalini through the different chakras is believed to achieve different levels of awakening and a mystical experience, until Kundalini finally reaches the top of the head, Sahasrara or crown chakra, producing an extremely profound transformation of consciousness. Energy is said to accumulate in the muladhara, and the yogi seeks to send it up to the brain transforming it into 'Ojas', the highest form of energy.

There are many physical effects that some people believe to be a

sign of a Kundalini awakening; however, there are also others who

contend that the undesirable side effects are not Kundalini but chakra

awakening. The following are either common signs of an awakened Kundalini or symptoms of a problem associated with an awakening Kundalini:

- Enlightenment

- Bliss, feelings of infinite love and universal connectivity, transcendent awareness, seeing truth (third eye opening), euphoria

- Awakened sense of smell, hearing, taste

- No longer controlled by desire/cravings

- Sound heard in the pineal gland (pleasurable/enjoyable)

- Change in the thyroid, sudden ability to sing in perfect pitch, change in voice

- Change in the sex organs

- Change in breathing

- Energy rushes or feelings of electricity circulating the body. This tingly feeling, at first, might be mistaken for a "shiver."

- Involuntary jerks, tremors, shaking, itching, tingling, and crawling sensations, especially in the arms and legs

- Intense heat (sweating) or cold, especially as energy is experienced passing through the chakras

- Spontaneous pranayama, asanas, mudras and bandhas

- Visions or sounds at times associated with a particular chakra

- Diminished or control over sexual desire

- Emotional upheavals or surfacing of unwanted and repressed feelings or thoughts with certain repressed emotions becoming dominant in the conscious mind for short or long periods of time.

- Headache, migraine, or pressure inside the skull. Relief of this pressure during an awakening may be felt as a "popping," depending on the person and their body at the time the awakening begins to occur.

- Pains in different areas of the body, especially back and neck

- Sensitivity to light, sound, and touch

- Trance-like and altered states of consciousness

- Disrupted sleep pattern (periods of insomnia or oversleeping)

- Vegetarianism or veganism

- Change in body odor (sweetness/natural/healthy)

Reports about the Sahaja Yoga technique of Kundalini awakening state that the practice can result in a cool breeze felt on the fingertips as well as the fontanel bone area. One study has measured a drop in temperature on the palms of the hands.

In his article on Kundalini in the Yoga Journal, David

Eastman narrates two personal experiences. One man said that he felt an

activity at the base of his spine starting to flow, so he relaxed and

allowed it to happen. A feeling of surging energy began traveling up his

back. At each chakra, he felt an orgasmic electric feeling like every

nerve trunk on his spine beginning to fire. A second man describes a

similar experience but accompanied by a wave of euphoria and happiness

softly permeating his being. He described the surging energy as being

like electricity but hot, traveling from the base of his spine to the

top of his head. He said the more he analyzed the experience, the less

it occurred.

In his book Building a Noble World, Shiv R. Jhawar describes his Kundalini awakening experience at Muktananda's public program at Lake Point Tower in Chicago on September 16, 1974, as follows:

"Baba [Swami Muktananda] had just begun delivering his discourse

with his opening statement: 'Today's subject is meditation. The crux of

the question is: What do we meditate upon?' Continuing his talk, Baba

said: 'Kundalini starts dancing when one repeats Om Namah Shivaya.'

Hearing this, I mentally repeated the mantra. I noticed that my

breathing was getting heavier. Suddenly, I felt a great impact of a

rising force within me. The intensity of this rising kundalini force was

so tremendous that my body lifted up a little and fell flat into the

aisle; my eyeglasses flew off. As I lay there with my eyes closed, I

could see a continuous fountain of dazzling white lights erupting within

me. In brilliance, these lights were brighter than the sun but

possessed no heat at all. I was experiencing the thought-free state of

"I am," realizing that "I" have always been, and will continue to be,

eternal. I was fully conscious and completely aware while I was

experiencing the pure "I am," a state of supreme bliss. Outwardly, at

that precise moment, Baba delightfully shouted from his platform...mene kuch nahi kiya; kisiko shakti ne pakda

(I didn't do anything. The Energy has caught someone.)' Baba noticed

that the dramatic awakening of kundalini in me frightened some people in

the audience. Therefore, he said, 'Do not be frightened. Sometimes

kundalini gets awakened in this way, depending upon a person's type.'

Kundalini experiences

Invoking Kundalini experiences

Several yogis consider that Kundalini can be awakened by shaktipat (spiritual transmission by a Guru or teacher), or by spiritual practices such as yoga or meditation.

There are two broad approaches to Kundalini awakening: active and passive. The active approach involves systematic physical exercises and techniques of concentration, visualization, pranayama

(breath practice) and meditation under the guidance of a competent

teacher. These techniques come from any of the four main branches of

yoga, and some forms of yoga, such as Kriya yoga, Kundalini yoga and Sahaja yoga.

The passive approach is instead a path of surrender where

one lets go of all the impediments to the awakening rather than trying

to actively awaken Kundalini. A chief part of the passive approach is shaktipat

where one individual's Kundalini is awakened by another who already has

the experience. Shaktipat only raises Kundalini temporarily but gives

the student an experience to use as a basis.

Gopi Krishna reports having experienced his first kundalini awakening at age 34. In his book Kundalini: Questions and Answers

he writes that while meditating upon a lotus in full bloom his

attention was drawn towards the crown of his head. He began to

experience a sensation of light as if it was entering his brain which

was at first distracting but soon began to acquire an enrapturing

condition. He felt it "like liquid light through all my nervous system,

in my stomach, in my heart, in my lungs, in my throat, in my head, and

taking control of the whole body. That was a most marvelous experience

for me, as if a new life energy had now taken possession of my body."

He subsequently came to believe "As the ancient writers have said, it is the vital force or prana

which is spread over both the macrocosm, the entire Universe, and the

microcosm, the human body... The atom is contained in both of these.

Prana is life-energy responsible for the phenomena of terrestrial life

and for life on other planets in the universe. Prana in its universal

aspect is immaterial. But in the human body, Prana creates a fine

biochemical substance which works in the whole organism and is the main

agent of activity in the nervous system and in the brain. The brain is

alive only because of Prana...

...The most important psychological changes in the character of an enlightened person would be that he or she would be compassionate and more detached. There would be less ego, without any tendency toward violence or aggression or falsehood. The awakened life energy is the mother of morality, because all morality springs from this awakened energy. Since the very beginning, it has been this evolutionary energy that has created the concept of morals in human beings.

American comparative religions scholar Joseph Campbell

describes the concept of Kundalini as "the figure of a coiled female

serpent—a serpent goddess not of "gross" but "subtle" substance—which is

to be thought of as residing in a torpid, slumbering state in a subtle

center, the first of the seven, near the base of the spine: the aim of

the yoga then being to rouse this serpent, lift her head, and bring her

up a subtle nerve or channel of the spine to the so-called

"thousand-petaled lotus" (Sahasrara)

at the crown of the head...She, rising from the lowest to the highest

lotus center will pass through and wake the five between, and with each

waking, the psychology and personality of the practitioner will be

altogether and fundamentally transformed."

Hatha yoga

According to the hatha yoga text, the Goraksasataka, or "Hundred Verses of Goraksa", certain hatha yoga practices including mula bandha, uddiyana bandha, jalandhara bandha and kumbhaka can awaken Kundalini. Another hathayoga text, the Khecarīvidyā, states that kechari mudra enables one to raise Kundalini and access various stores of amrita in the head, which subsequently flood the body.

Shaktipat

The spiritual teacher Meher Baba emphasized the need for a master when actively trying to awaken Kundalini:

Kundalini is a latent power in the higher body. When awakened, it pierces through six chakras or functional centers and activates them. Without a master, the awakening of the kundalini cannot take anyone very far on the Path; and such indiscriminate or premature awakening is fraught with dangers of self-deception as well as the misuse of powers. The kundalini enables man to consciously cross the lower planes and it ultimately merges into the universal cosmic power of which it is a part, and which also is at times described as kundalini ... The important point is that the awakened kundalini is helpful only up to a certain degree, after which it cannot ensure further progress. It cannot dispense with the need for the grace of a Perfect Master.

Kundalini awakening while prepared or unprepared

The experience of Kundalini awakening can happen when one is either prepared or unprepared.

Preparedness

According

to Hindu tradition, in order to be able to integrate this spiritual

energy, a period of careful purification and strengthening of the body

and nervous system is usually required beforehand. Yoga and Tantra propose that Kundalini can be awakened by a guru (teacher), but body and spirit must be prepared by yogic austerities, such as pranayama,

or breath control, physical exercises, visualization, and chanting. The

student is advised to follow the path in an open-hearted manner.

Traditionally, people would visit ashrams in India to awaken

their dormant kundalini energy. Typical activities would include regular

meditation, mantra chanting, spiritual studies as well as a physical

asana practice such as kundalini yoga.

Spontaneously

The

Kundalini always awakens spontaneously when the person least expects

it. Whether prepared or unprepared, the kundalini rises despite any

attempt to stop it by the sadhak.

Religious interpretations

Indian interpretations

Kundalini is considered to occur in the chakra and nadis of the subtle body. Each chakra is said to contain special characteristics and with proper training, moving Kundalini through these chakras can help express or open these characteristics.

Kundalini is described as a sleeping, dormant potential force in the human organism. It is one of the components of an esoteric description of the "subtle body", which consists of nadis (energy channels), chakras (psychic centres), prana (subtle energy), and bindu (drops of essence).

Kundalini is described as being coiled up at the base of the

spine. The description of the location can vary slightly, from the

rectum to the navel. Kundalini is said to reside in the triangular shaped sacrum bone in three and a half coils.

Ramana Maharshi mentioned that Kundalini is nothing but the natural energy of the Self, where Self is the universal consciousness (Paramatma) present in every being and that the individual mind of thoughts cloaks this natural energy from unadulterated expression. Advaita teaches self-realization, enlightenment, God-consciousness, and nirvana.

But initial Kundalini awakening is just the beginning of the actual

spiritual experience. Self-inquiry meditation is considered a very

natural and simple means of reaching this goal.

Swami Vivekananda describes Kundalini briefly in his book Raja Yoga as follows:

According to the Yogis, there are two nerve currents in the spinal column, called Pingalâ and Idâ, and a hollow canal called Sushumnâ running through the spinal cord. At the lower end of the hollow canal is what the Yogis call the "Lotus of the Kundalini". They describe it as triangular in a form in which, in the symbolical language of the Yogis, there is a power called the Kundalini, coiled up. When that Kundalini awakens, it tries to force a passage through this hollow canal, and as it rises step by step, as it were, layer after layer of the mind becomes open and all the different visions and wonderful powers come to the Yogi. When it reaches the brain, the Yogi is perfectly detached from the body and mind; the soul finds itself free. We know that the spinal cord is composed in a peculiar manner. If we take the figure eight horizontally (∞), there are two parts which are connected in the middle. Suppose you add eight after eight, piled one on top of the other, that will represent the spinal cord. The left is the Ida, the right Pingala, and that hollow canal which runs through the center of the spinal cord is the Sushumna. Where the spinal cord ends in some of the lumbar vertebrae, a fine fiber issues downwards, and the canal runs up even within that fiber, only much finer. The canal is closed at the lower end, which is situated near what is called the sacral plexus, which, according to modern physiology, is triangular in form. The different plexuses that have their centers in the spinal canal can very well stand for the different "lotuses" of the Yogi.

When Kundalini Shakti is conceived as a goddess, then, when it rises to the head, it unites itself with the Supreme Being of (Lord Shiva). The aspirant then becomes engrossed in deep meditation and infinite bliss. Paramahansa Yogananda in his book God Talks With Arjuna: The Bhagavad Gita states:

At the command of the yogi in deep meditation, this creative force turns inward and flows back to its source in the thousand-petaled lotus, revealing the resplendent inner world of the divine forces and consciousness of the soul and spirit. Yoga refers to this power flowing from the coccyx to spirit as the awakened kundalini.

Paramahansa Yogananda also states:

The yogi reverses the searchlights of intelligence, mind and life force inward through a secret astral passage, the coiled way of the kundalini in the coccygeal plexus, and upward through the sacral, the lumbar, and the higher dorsal, cervical, and medullary plexuses, and the spiritual eye at the point between the eyebrows, to reveal finally the soul's presence in the highest center (Sahasrara) in the brain.

Western significance

Sir John Woodroffe

(1865–1936) – also known by his pseudonym Arthur Avalon – was a British

Orientalist whose published works stimulated a far-reaching interest in

Hindu philosophy and Yogic practices. While serving as a High Court Judge in Calcutta, he studied Sanskrit and Hindu Philosophy, particularly as it related to Hindu Tantra. He translated numerous original Sanskrit texts and lectured on Indian Philosophy, Yoga and Tantra. His book, The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga became a major source for many modern Western adaptations of Kundalini yoga

practice. It presents an academically and philosophically sophisticated

translation of, and commentary on, two key Eastern texts: Shatchakranirūpana (Description and Investigation into the Six Bodily Centers) written by Tantrik Pūrnānanda Svāmī (1526) and the Paduka-Pancakā

from the Sanskrit of a commentary by Kālīcharana (Five-fold Footstool

of the Guru). The Sanskrit term "Kundali Shakti" translates as "Serpent

Power". Kundalini is thought to be an energy released within an

individual using specific meditation techniques. It is represented

symbolically as a serpent coiled at the base of the spine.

In his preface to The Serpent Power Woodroffe clarifies the concept of Kundalini:

Vivified by the “Serpent Fire”( Kundalini) they (chakras) become gates of connection between the physical and “astral” bodies. When the astral awakening of these centers first took place, this was not known to the physical consciousness. But the sense body can now “be brought to share all these advantages by repeating that process of awakening with the etheric centers. This is done by the arousing through will-force of the “Serpent Fire,” which exists clothed in “etheric matter in the physical plane, and sleeps in the corresponding etheric center—that at the base of the spine. When this is done, it vivifies the higher centers, with the effect that it brings into the physical consciousness the powers which are aroused by the development of their corresponding astral centers. . . There mere rousing of the Serpent Power does not, from the spiritual Yoga standpoint, amount too much. Nothing, however, of real moment, from the higher Yogi’s point of view, is achieved until the Ajna Cakra is reached. Here, again, it is said that the Sadhaka whose Atma is nothing but a meditation on the lotus “becomes the creator, preserver and destroyer of the three worlds”…It is not until the Tattvas of this center are also absorbed, and complete knowledge of the Sahasrara is gained, that the Yogi attains that which is both his aim and the motive of his labor, cessation from rebirth which follows on the control and concentration of the Citta on the Siva-sthanam, the Abode of Bliss.

In his book Artistic Form and Yoga in the Sacred Images of India, Heinrich Zimmer spoke highly of Woodroffe's works:

The values of the Hindu tradition were disclosed to me through the enormous life-work of Sir John Woodroffe, alias Arthur Avalon, a pioneer and a classic author in Indie studies, second to none, who, for the first time, by many publications and books made available the extensive and complex treasure of late Hindu tradition: the Tantras, a period as grand and rich as the Vedas, the Epic, Puranas, etc.; the latest crystallization of Indian wisdom, the indispensable closing link of a chain, affording keys to countless problems in the history of Buddhism and Hinduism, in mythology and symbolism.

When Woodroffe later commented upon the reception of his work he

clarified his objective, "All the world (I speak of course of those

interested in such subjects) is beginning to speak of Kundalinî Shakti."

He described his intention as follows: "We, who are foreigners, must

place ourselves in the skin of the Hindu, and must look at their doctrine and ritual through their eyes and not our own."

Western awareness of kundalini was strengthened by the interest of Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Dr. Carl Jung

(1875–1961). Jung's seminar on Kundalini yoga presented to the

Psychological Club in Zurich in 1932 was widely regarded as a milestone

in the psychological understanding of Eastern thought and of the symbolic transformations of inner experience. Kundalini yoga presented Jung with a model for the developmental phases of higher consciousness,

and he interpreted its symbols in terms of the process of

individuation, with sensitivity towards a new generation's interest in

alternative religions and psychological exploration.

In the introduction to Jung's book The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga, Sonu Shamdasani

puts forth "The emergence of depth psychology was historically

paralleled by the translation and widespread dissemination of the texts

of yoga... for the depth psychologies sought to liberate themselves from

the stultifying limitations of Western thought to develop maps of inner

experience grounded in the transformative potential of therapeutic

practices. A similar alignment of "theory" and "practice" seemed to be

embodied in the yogic texts that moreover had developed independently of

the bindings of Western thought. Further, the initiatory structure

adopted by institutions of psychotherapy brought its social organization

into proximity with that of yoga. Hence, an opportunity for a new form

of comparative psychology opened up."

The American writer William Buhlman, began to conduct an

international survey of out-of-body experiences in 1969 in order to

gather information about symptoms: sounds, vibrations and other

phenomena, that commonly occur at the time of the OBE event. His

primary interest was to compare the findings with reports made by yogis,

such as Gopi Krishna (yogi) who have made reference to similar phenomenon, such as the 'vibrational state' as components of their kundalini-related spiritual experience. He explains:

There are numerous reports of full Kundalini experiences culminating with a transcendental out-of-body state of consciousness. In fact, many people consider this experience to be the ultimate path to enlightenment. The basic premise is to encourage the flow of Kundalini energy up the spine and toward the top of the head—the crown chakra—thus projecting your awareness into the higher heavenly dimensions of the universe. The result is an indescribable expansion of consciousness into spiritual realms beyond form and thought.

George King (1919–1997), founder of the Aetherius Society,

describes the concept of Kundalini throughout his works and claimed to

have experienced this energy many times throughout his life while in a

"positive samadhic yogic trance state".

According to King,

It should always be remembered that despite appearances to the contrary, the complete control of Kundalini through the spinal column is man's only reason for being on Earth, for when this is accomplished, the lessons in this classroom and the mystical examination is passed.

In his lecture entitled The Psychic Centers – Their Significance and Development,

he describes the theory behind the raising of Kundalini and how this

might be done safely in the context of a balanced life devoted to

selfless service.

Sri Aurobindo

was the other great authority scholar on Kundalini parallel to

Woodroffe with a somewhat different viewpoint, according to Mary Scott

(who is herself a latter-day scholar on Kundalini and its physical

basis) and was a member of the Theosophical Society.

Other well-known spiritual teachers who have made use of the idea of Kundalini include Aleister Crowley, whose Gnostic Mass

symbolically incorporates the concept via various means including the

entrance procession ('circumambulation') of the Priest and Priestess; Albert Rudolph (Rudi), Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (Osho), George Gurdjieff, Paramahansa Yogananda, Sivananda Radha Saraswati, who produced an English language guide to Kundalini yoga methods, Muktananda, Bhagawan Nityananda, Yogi Bhajan, Nirmala Srivastava, Samael Aun Weor.

New Age

Kundalini references may be found in a number of New Age presentations, and is a word that has been adopted by many new religious movements.

Psychology

According to Carl Jung "... the concept of Kundalini has for us only one use, that is, to describe our own experiences with the unconscious ..."

Jung used the Kundalini system symbolically as a means of understanding

the dynamic movement between conscious and unconscious processes. He

cautioned that all forms of yoga, when used by Westerners, can be

attempts at domination of the body and unconscious through the ideal of

ascending into higher chakras.

According to Shamdasani, Jung claimed that the symbolism of

Kundalini yoga suggested that the bizarre symptomatology that patients

at times presented, actually resulted from the awakening of the

Kundalini. He argued that knowledge of such symbolism enabled much that

would otherwise be seen as the meaningless by-products of a disease

process to be understood as meaningful symbolic processes, and

explicated the often peculiar physical localizations of symptoms.

Recently, there has been a growing interest within the medical community to study the physiological effects of meditation, and some of these studies have applied the discipline of Kundalini yoga to their clinical settings.

The popularization of eastern spiritual practices has been

associated with psychological problems in the west. Psychiatric

literature notes that "since the influx of eastern spiritual practices

and the rising popularity of meditation starting in the 1960s, many

people have experienced a variety of psychological difficulties, either

while engaged in intensive spiritual practice or spontaneously".

Among the psychological difficulties associated with intensive

spiritual practice we find "Kundalini awakening", "a complex

physio-psychospiritual transformative process described in the yogic

tradition". Researchers in the fields of Transpersonal psychology, and Near-death studies

have described a complex pattern of sensory, motor, mental and

affective symptoms associated with the concept of Kundalini, sometimes

called the Kundalini syndrome.

The differentiation between spiritual emergency associated with Kundalini awakening may be viewed as an acute psychotic episode

by psychiatrists who are not conversant with the culture. The

biological changes of increased P300 amplitudes that occurs with certain

yogic practices may lead to acute psychosis. Biological alterations by

Yogic techniques may be used to warn people against such reactions.

Some modern experimental research seeks to establish links between Kundalini practice and the ideas of Wilhelm Reich and his followers.