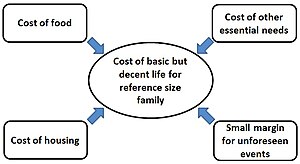

Cost of a basic but decent life for a family.

A living wage is the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs.

Needs are defined to include food, housing, and other essential needs

such as clothing. The goal of a living wage is to allow a worker to

afford a basic but decent standard of living.

Due to the flexible nature of the term "needs", there is not one

universally accepted measure of what a living wage is and as such it

varies by location and household type.

A living wage, in some nations such as the United Kingdom and New Zealand,

generally means that a person working 40 hours a week, with no

additional income, should be able to afford the basics for a modest but

decent life, such as, food, shelter, utilities, transport, health care, and child care. Living wage advocates have further defined a living wage as the wage equivalent to the poverty line

for a family of four. The income would have to allow the family to

'secure food, shelter, clothing, health care, transportation and other

necessities of living in modern society'. A definition of a living wage used by the Greater London Authority

(GLA) is the threshold wage, calculated as an income of 60% of the

median, and an additional 15% to allow for unforeseen events.

Calculating a living wage

The living wage differs from the minimum wage

in that the latter is set by national law and can fail to meet the

requirements to have a basic quality of life which leaves the family to

rely on government programs for additional income. Living wages, on the other hand, have typically only been adopted in municipalities. In economic terms, the living wage is similar to the minimum wage as it is a price floor for labor.

In the 1990s, the first contemporary living wage campaigns were

launched by community initiatives in the US addressing increasing

poverty faced by workers and their families. They argued that the

employee, employer, and community all benefited with a living wage.

Employees would be more willing to work, helping the employer reduce worker turnover, and it would help the community when the citizens have enough to have a decent life. These campaigns came about partially as a response to Reaganomics and Thatcherism in the US and UK, respectively, which shifted macroeconomic policy towards neoliberalism. A living wage, by increasing the purchasing power of low income workers, is supported by Keynesian and post-Keynesian economics which focuses on stimulating demand in order to improve the state of the economy.

History

The concept of a living wage, though it was not defined as such, can

be traced back to the works of ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle. Both argued for an income that considers needs, particularly those that ensure the communal good.

Aristotle saw self-sufficiency as a requirement for happiness which he

defined as, ‘that which on its own makes life worthy of choice and

lacking in nothing’.

As he placed the responsibility in ensuring that the poor could earn a

sustainable living in the state, his ideas are seen as an early example

of support for a living wage. The evolution of the concept can be seen

later on in medieval scholars such as Thomas Aquinas who argued for a 'just wage'. The concept of a just wage was related to that of just prices,

which were those that allowed everyone access to necessities. Prices

and wages that prevented access to necessities were considered unjust as

they would imperil the virtue of those without access.

In Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

recognized that rising real wages lead to the "improvement in the

circumstances of the lower ranks of people" and are therefore an

advantage to society.

Growth and a system of liberty were the means by which the laboring

poor were able to secure higher wages and an acceptable standard of

living. Rising real wages are secured by growth through increasing

productivity against stable price levels, i.e. prices not affected by

inflation. A system of liberty, secured through political institutions

whereupon even the "lower ranks of people" could secure the opportunity

for higher wages and an acceptable standard of living.

Servants, labourers and workmen of different kinds, make up the far greater part of every great political society. But what improves the circumstances of the greater part can never be regarded as an inconvenience to the whole. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed and lodged.

— Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, I .viii.36

Based on these writings, Smith advocated that labor should receive an

equitable share of what labor produces. For Smith, this equitable share

amounted to more than subsistence. Smith equated the interests of

labor and the interests of land with overarching societal interests. He

reasoned that as wages and rents rise, as a result of higher

productivity, societal growth will occur thus increasing the quality of

life for the greater part of its members.

Like Smith, supporters of a living wage argue that the greater

good for society is achieved through higher wages and a living wage. It

is argued that government should in turn attempt to align the interests

of those pursuing profits with the interests of the labor in order to

produce societal advantages for the majority of society. Smith argued

that higher productivity and overall growth led to higher wages that in

turn led to greater benefits for society. Based on his writings, one

can infer that Smith would support a living wage commensurate with the

overall growth of the economy. This, in turn, would lead to more

happiness and joy for people, while helping to keep families and people

out of poverty. Political institutions can create a system of liberty

for individuals to ensure opportunity for higher wages through higher

production and thus stable growth for society.

In 1891, Pope Leo XIII issued a papal bull entitled Rerum novarum,

which is considered the Catholic Church's first expression of a view

supportive of a living wage. The church recognized that wages should be

sufficient to support a family.

This position has been widely supported by the church since that time,

and has been reaffirmed by the papacy on multiple occasions, such as by

Pope Pius XI in 1931 Quadragesimo anno and again in 1961, by Pope John XXIII writing in the encyclical Mater et magistra. More recently, Pope John Paul II

wrote, "Hence in every case a just wage is the concrete means of

verifying the whole socioeconomic system and, in any case, of checking

that it is functioning justly."

Contemporary thought

Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and for his family an existence worthy of human dignity. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Art. 23 Sec. 3

Different ideas on a living wage have been advanced by modern

campaigns that have pushed for localities to adopt them. Supporters of a

living wage have argued that a wage is more than just compensation for

labour. It is a means of securing a living and it leads to public

policies that address both the level of the wage and its decency. Contemporary research by Andrea Werner and Ming Lim has analyzed the works of John Ryan, Jerold Waltman and Donald Stabile for their philosophical and ethical insights on a living wage.

John Ryan argues for a living wage from a rights perspective. He

considers a living wage to be a right that all labourers are entitled

to from the 'common bounty of nature'.

He argues that private ownership of resources precludes access to them

by others who would need them to maintain themselves. As such, the

obligation to fulfill the right of a living wage rests on the owners and

employers of private resources. His argument goes beyond that a wage

should provide mere subsistence but that it should provide humans with

the capabilities to 'develop within reasonable limits all [their]

faculties, physical, intellectual, moral and spiritual.' A living wage for him is 'the amount of remuneration that is sufficient to maintain decently the laborer'.

Jerold Waltman, in A Case for the Living Wage, argues for a living wage not based on individual rights but from a communal, or 'civic republicanism',

perspective. He sees the need for citizens to be connected to their

community, and thus, sees individual and communal interests as

inseparably bound. Two major problems that are antithetical to civic republicanism

are poverty and inequality. A living wage is meant to address these by

providing the material basis that allows individuals a degree of

autonomy and prevents disproportionate income and wealth that would

inevitably lead to a societal fissure between the rich and poor. A

living wage further allows for political participation by all classes of

people which is required to prevent the political interests of the rich

from undermining the needs of the poor. These arguments for a living

wage, taken together, can be seen as necessary elements for 'social

sustainability and cohesion'.

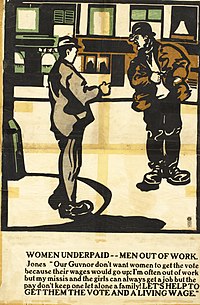

Waiting for a living wage poster (1913)

Donald Stabile argues for a living wage based on moral economic thought and its related themes of sustainability, capability and externality.

Broadly speaking, Stabile indicates that sustainability in the economy

may require that people have the means for 'decent accommodation,

transport, clothing and personal care'.

He qualifies the statement as he sees individual necessities as

contextual and therefore able to change over time, between cultures and

under different macroeconomic circumstances.

This suggests that the concept and definition of a living wage cannot

be made objective over all places and in all times. Stabile's thoughts

on capabilities make direct reference to Amartya Sen's work on capability approach.

The tie-in with a living wage is the idea that income is an important,

though not exclusive, means for capabilities. The enhancement of

people's capabilities allows them to better function both in society and

as workers. These capabilities are further passed down from parents to

children. Finally, Stabile analyses the lack of a living wage as the

imposition of negative externalities on others. These externalities take the form of depleting the stock of workers by 'exploiting and exhausting the workforce'.

This leads to economic inefficiency as businesses end up overproducing

their products due to not paying the full cost of labour.

Other contemporary accounts have taken up the theme of externalities

arising due to a lack of living wage. Muilenburg and Singh see welfare

programs, such as housing and school meals, as being a subsidy for

employers that allow them to pay low wages.

This subsidy, taking the form of an externality, is of course paid for

by society in the form of taxes. This thought is repeated by Grimshaw

who argues that employers offset the social costs of maintaining their

workforce through tax credits, housing, benefits and other wage

subsidies. The issue was raised during the Democratic party primary election of 2016 in the United States, when presidential candidate Bernie Sanders

mentioned that "struggling working families should not have to

subsidise the wealthiest family in the country", and therefore, implied

that the large retailer Walmart, who is owned by the wealthiest family in the country, was not paying fair wages and was being subsidised by taxpayers.

Implementations

Australia

Living wage inquiry in Sydney, Australia. (1935)

In Australia, the 1907 Harvester Judgement

ruled that an employer was obliged to pay his employees a wage that

guaranteed them a standard of living which was reasonable for "a human

being in a civilised community" to live in "frugal comfort estimated by

current... standards," regardless of the employer's capacity to pay. Justice Higgins established a wage of 7/- (7 shillings)

per day or 42/- per week as a 'fair and reasonable' minimum wage for

unskilled workers. The judgement was later overturned but remains

influential. From the Harvester Judgement arose the Australian

industrial concept of the "basic wage". For most skilled workers, in

addition to the basic wage they received a margin

on top of the basic wage, in proportion to a court or commission's

judgement of a group of worker's skill levels. In 1913, to compensate

for the rising cost of living, the basic wage was increased to 8/- per

day, the first increase since the minimum was set. The first Retail Price Index in Australia was published late in 1912, the A Series Index. From 1934, the basic wage was indexed against the C Series Index of household prices. The concept of a basic wage was repeatedly challenged by employer groups through the Basic wage cases and Metal Trades Award cases

where the employers argued that the basic wage and margin ought to be

replaced by a "total wage". The basic wage system remained in place in

Australia until 1967. It was also adopted by some state tribunals and

was in use in some states during the 1980s.

Bangladesh

In

Bangladesh salaries are among the lowest in the world. During 2012

wages hovered around US$38 per month depending on the exchange rate.

Studies by Professor Doug Miller during 2010 to 2012, has highlighted

the evolving global trade practices in Towards Sustainable Labour Costing in UK Fashion Retail.

This white paper published in 2013 by University of Manchester,

appears to suggest that the competition among buying organisation has

implications to low wages in countries such as Bangladesh. It has laid

down a road map to achieve sustainable wages.

United Kingdom

| Country | Hourly

(LCU)

|

Hourly

(US$)

|

|---|---|---|

| Canada |

|

|

| Calgary Toronto Vancouver |

C$18.15 C$18.52 C$20.91 |

$13.96 $14.25 $16.08 |

| Ireland |

|

|

| National | €11.90 | $13.42 |

| New Zealand |

|

|

| National | NZ$20.50 | $14.54 |

| United Kingdom |

|

|

| National London |

£8.75 £10.20 |

$11.22 $13.08 |

| United States |

|

|

| National Los Angeles New York City San Francisco |

$16.07 $18.95 $21.55 $23.79 |

$16.07 $18.95 $21.55 $23.79 |

Municipal regulation of wage levels began in some towns in the United Kingdom in 1524. National minimum wage law began with the Trade Boards Act 1909, and the Wages Councils Act 1945

set minimum wage standards in many sectors of the economy. Wages

Councils were abolished in 1993 and subsequently replaced with a single

statutory national minimum wage by the National Minimum Wage Act 1998, which is still in force. The rates are reviewed each year by the country's Low Pay Commission. From 1 April 2016 the minimum wage has been paid as a mandatory National Living Wage

for workers over 25. It is being phased in between 2016 and 2020 and is

set at a significantly higher level than previous minimum wage rates.

By 2020 it is expected to have risen to at least £9 per hour and

represent a full-time annual pay equivalent to 60% of the median UK

earnings. The National Living Wage is nevertheless lower than the value of the Living Wage calculated by the Living Wage Foundation.

Some organisations voluntarily pay a living wage to their staff, at a

level somewhat higher than the statutory level. From September 2014 all NHS Wales

staff have been paid a minimum of the "living wage" recommended by the

Living Wage Commission. About 2,400 employees received an initial salary

increase of up to £470 above the UK-wide Agenda for Change rates.

United States

In the United States, the state of Maryland

and several municipalities and local governments have enacted

ordinances which set a minimum wage higher than the federal minimum that

requires all jobs to meet the living wage for that region. This usually

works out to be $3 to $7 above the federal minimum wage. However, San Francisco, California and Santa Fe, New Mexico have notably passed very wide-reaching living wage ordinances. U.S. cities with living wage laws include Santa Fe and Albuquerque in New Mexico; San Francisco, California; and Washington, D.C.[36] The city of Chicago, Illinois also passed a living wage ordinance in 2006, but it was vetoed by Mayor Richard M. Daley. Living wage laws typically cover only businesses that receive state assistance or have contracts with the government.

This effort began in 1994 when an alliance between a labor union and religious leaders in Baltimore launched a successful campaign requiring city service contractors to pay a living wage. Subsequent to this effort, community advocates have won similar ordinances in cities such as Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and St. Louis.

In 2007, there were at least 140 living wage ordinances in cities

throughout the United States and more than 100 living wage campaigns

underway in cities, counties, states, and college campuses.

In 2014, Wisconsin Service Employees International Union teamed up with

public officials against legislation to eliminate local living wages.

According to U.S. Department of Labor data, Wisconsin Jobs Now - a

non-profit organization fighting inequality through higher wages - has

received at least $2.5 million from SEIU organizations from 2011 to

2013.

Although these ordinances are recent, a number of studies have

attempted to measure the impact of these policies on wages and

employment. Researchers have had difficulty measuring the impact of

these policies because it is difficult to isolate a control group for

comparison. A notable study defined the control group as the subset of

cities that attempted to pass a living wage law but were unsuccessful.

This comparison indicates that living wages raise the average wage

level in cities, however, it reduces the likelihood of employment for

individuals in the bottom percentile of wage distribution.

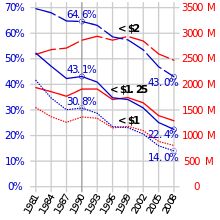

Impact

Research

shows that minimum wage laws and living wage legislation impact poverty

differently: evidence demonstrates that living wage legislation reduces

poverty.

The parties impacted by minimum wage laws and living wage laws differ

as living wage legislation generally applies to a more limited sector of

the population. It is estimated that workers who qualify for the living

wage legislation are currently between 1-2% of the bottom quartile of

wage distribution. One must consider that the impact of living wage laws depends heavily on the degree to which these ordinances are enforced.

Neumark and Adams, in their paper, "Do living wage ordinances

reduce urban poverty?", state, "There is evidence that living wage

ordinances modestly reduce the poverty rates in locations in which these

ordinances are enacted. However, there is no evidence that state

minimum wage laws do so."

A study carried out in Hamilton, Canada by Zeng and Honig indicated that living wage workers have higher affective commitment and lower turnover intention.

Workers paid a living wage were more likely to support the

organization they work for in various ways including: "protecting the

organizations public image, helping colleagues solve problems, improving

their skills and techniques, providing suggestions or advice to a

management team, and caring about the organization." The authors interpret these finding through social exchange theory,

which points out the mutual obligation employers and employees feel

towards each other when employees perceive they are provided favorable

treatment.

The current minimum national minimum wage in the United States,

does not support a livable wage for the employees. Due to the fact that

they are underpaid, the reliance on federal and state aid is inflated.

It is estimated that if there would be a savings of approximately 18

billion dollars in federal aid if the minimum wage was raised to 12

dollars an hour. Some of the other benefits to the employees would be

increased self-esteem and job satisfaction, which would also trickle

down to the children of those workers. These children would see improved

social environments and perhaps more success at school due to this

support. With the increase in wage, the employee would also have an

increased buying power which would help stimulate the economy and create

more jobs.

Living wage estimates

As of 2003, there are 122 living wage ordinances in American cities and an additional 75 under discussion. Article 23 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

states that "Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable

remuneration ensuring for himself and for his family an existence worthy

of human dignity."

In addition to legislative acts, many corporations have adopted voluntary codes of conduct. The Sullivan Principles

in South Africa are an example of a voluntary code of conduct which

state that firms should compensate workers to at least cover their basic

needs.

In the table below, cross national comparable living wages were

estimated for twelve countries and reported in local currencies and purchasing power parity

(PPP). Living wage estimates for the year 2000 range from US $1.7 PPP

per hour, in low-income examples, to approximately US$11.6 PPP per hour,

in high-income examples.

| Country | One full-time worker (four person household) | Average number of full-time worker equivalents in country (four person household) | One full-time worker (household size varies by country) | Average number of full-time worker equivalents in each country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 1.61 | 1.14 | 2.02 | 1.44 |

| India | 1.55 | 1.32 | 1.79 | 1.52 |

| Zimbabwe | 2.43 | 1.70 | 3.18 | 2.22 |

| Low income average | 1.86 | 1.39 | 2.33 | 1.72 |

| Armenia | 3.03 | 2.05 | 2.52 | 1.70 |

| Ecuador | 1.94 | 1.74 | 2. 23 | 2.01 |

| Egypt | 1.96 | 1.77 | 2.45 | 2.21 |

| China | 2.08 | 1.47 | 1.95 | 1.38 |

| South Africa | 3.10 | 2.60 | 3.35 | 2.81 |

| Lower middle income average | 2.42 | 1.93 | 2.50 | 2.02 |

| Lithuania | 4.62 | 3.21 | 3.97 | 2.76 |

| Costa Rica | 3.68 | 3.38 | 3.90 | 3.58 |

| Upper middle income average | 4.14 | 3.30 | 3.94 | 3.17 |

| United States | 13.10 | 11.00 | 13.36 | 11.23 |

| Switzerland | 16.41 | 13.23 | 14.76 | 11.91 |

| High income average | 14.75 | 12.10 | 14.06 | 11.57 |

Living wage movements

Living Wage Foundation

Workers protesting for a living wage in London, United Kingdom. (2017)

The Living Wage Campaign in the United Kingdom originated in London,

where it was launched in 2001 by members of the community organisation

London Citizens (now Citizens UK). It engaged in a series of Living Wage campaigns and in 2005 the Greater London Authority

established the Living Wage Unit to calculate the London Living Wage,

although the authority had no power to enforce it. The London Living

Wage was developed in 2008 when Trust for London awarded a grant of over

£1 million for campaigning, research and an employer accreditation

scheme. The Living Wage campaign subsequently grew into a national

movement with local campaigns across the UK. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation funded the Centre for Research in Social Policy (CRSP) at Loughborough University

to calculate a UK-wide Minimum Income Standard (MIS) figure, an average

across the whole of the UK independent of the higher living costs in

London.

In 2011 the CRSP used the MIS as the basis for developing a standard model for setting the UK Living Wage outside of London. Citizens UK, a nationwide community organising institution developed out of London Citizens, launched the Living Wage Foundation and Living Wage Employer mark.

Since 2011, the Living Wage Foundation has accredited over 1,800

employers that pay its proposed living wage. The living wage in London

is calculated by GLA Economics and the CRSP calculates the out-of-London

Living Wage. Their recommended rates for 2015 are £9.40 for London and

£8.25 for the rest of the UK.

These rates are updated annually in November. In January 2016 the

Living Wage Foundation set up a new Living Wage Commission to oversee

the calculation of the Living Wage rates in the UK.

In 2012, research into the costs and benefits of a living wage in London was funded by the Trust for London and carried out by Queen Mary University of London.

Further research was published in 2014 in a number of reports on the

potential impact of raising the UK's statutory national minimum wage to

the same level as the Living Wage Foundation's living wage

recommendation. This included two reports funded by the Trust for London and carried out by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) and Resolution Foundation: "Beyond the Bottom Line" and "What Price a Living Wage?" Additionally, Landman Economics published "The Economic Impact of Extending the Living Wage to all Employees in the UK".

A 2014 report by the Living Wage Commission, chaired by Doctor John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York,

recommended that the UK government should pay its own workers a "living

wage", but that it should be voluntary for the private sector. Data published in late 2014 by New Policy Institute

and Trust for London found 20% of employees in London were paid below

the Living Wage Foundation's recommended living wage between 2011 and

2013. The proportion of residents paid less than this rate was highest

in Newham (37%) and Brent (32%). Research by the Office for National Statistics

in 2014 indicated that at that time the proportion of jobs outside

London paying less than the living wage was 23%. The equivalent figure

within London was 19%.

Research by Loughborough University, commissioned by Trust for London,

shows 4 in 10 Londoners cannot afford a decent standard of living - that

is one that allows them to meet their basic needs and participate in

society at a minimum level. This is significantly higher than the 30%

that fall below the standard in the UK as a whole. This represents 3.5

million Londoners, an increase of 400,000 since 2010/11. The research

highlights the need to improve incomes through better wages, mainly, the

London Living Wage, to ensure more Londoners reach a decent standard of

living.

Ed Miliband, the leader of the Labour Party in opposition from 2010 until 2015, supported a living wage and proposed tax breaks for employers who adopted it. The Labour Party has implemented a living wage in some local councils which it controls, such as in Birmingham and Cardiff councils. The Green Party

also supports the introduction of a living wage, believing that the

national minimum wage should be 60% of net national average earnings. Sinn Féin also supports the introduction of a living wage for Northern Ireland. Other supporters include The Guardian newspaper columnist Polly Toynbee, Church Action on Poverty, the Scottish Low Pay Unit, and Bloomsbury Fightback!.

Living Wage Movement Aotearoa New Zealand

In New Zealand

a new social movement, Living Wage Movement Aotearoa New Zealand, was

formed in April 2013. It emerged from a loose network that launched a

Living Wage Campaign in May 2012. In 2015 there were over 50 faith,

union and community member organisations and by 2017 there were 90.

In February 2013, independent research by the Family Centre

Social Policy Research Unit identified the New Zealand Living Wage as

$18.40 per hour. This was increased in 2014 to $18.80 per hour and by

2017 to $20.20 per hour.

On July 1, 2014 the first accredited NZ Living Wage Employers

were announced. The twenty businesses for 2014-15 included food

manufacturing, social service agencies, community organisations, unions,

and a restaurant. This number has now increased to 90 businesses,

including the first corporate, Vector. Wellington City Council has

committed to becoming an accredited Living Wage Employer and five other

local government bodies, including Auckland Council, have taken their

first steps toward implementing the Living Wage. In the election of

September 2017 the three parties that form the Government have also

committed to a Living Wage for employees and contracted workers to the

core public service.

Asia Floor Wage

Launched

in 2009, Asia Floor Wage is a loose coalition of labour and other

groups seeking to implement a Living Wage throughout Asia, with a

particular focus on textile manufacturing.

There are member associations in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Hong Kong

S.A.R., India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri

Lanka, Thailand and Turkey as well as supporters in Europe and North

America. The campaign targets multinational employers who do not pay

their developing world workers a living wage.

United States living wage campaigns

New York City

March for a living wage in Seattle, United States. (2014)

The proposed law will inform tax-payers of where their investment

dollars go and will hold developers to more stringent employment

standards. The proposed act will require developers who receive

substantial tax-payer funded subsidies to pay employees a minimum living

wage. The law is designed to raise quality of life and stimulate local

economy. Specifically the proposed act will guarantee that workers in

large developmental projects will receive a wage of at least $10.00 an

hour. The living wage will get indexed so that it keeps up with cost of

living increases. Furthermore, the act will require that employees who

do not receive health insurance from their employer will receive an

additional $1.50 an hour to subsidize their healthcare expenses. Workers

employed at a subsidized development will also be entitled to the

living wage guarantee.

Many city officials have opposed living wage requirements because

they believe that they restrict business climate thus making cities

less appealing to potential industries. Logistically cities must hire

employees to administer the ordinance. Conversely advocates for the

legislation have acknowledged that when wages aren't sufficient,

low-wage workers are often forced to rely on public assistance in the form of food stamps or Medicaid.

James Parrott of the Fiscal Policy Institute

testified during a May 2011 New York City Council meeting that real

wages for low-wage workers in the city have declined substantially over

the last 20 years, despite dramatic increases in average education

levels. A report

by the Fiscal Policy Institute indicated that business tax subsidies

have grown two and a half times faster than overall New York City tax

collections and asks why these public resources are invested in

poverty-level jobs. Mr. Parrott testified that income inequality in New York City exceeds that of other large cities, with the highest-earning 1 percent receiving 44 percent of all income.

Harvard University

Harvard University

students began organizing a campaign to combat the issue of low living

wages for Harvard workers beginning in 1998. After failed attempts to

get a meeting with Harvard president Neil Rudenstine,

The Living Wage Campaign began to take action. As the movement gained

momentum, The Living Wage Campaign held rallies with the support of

students, alumni, faculty, staff, community members and organizations.

Most importantly, the rallies gained the support of the Harvard workers,

strengthening the campaign's demands for a higher wage. After various

measures trying to provoke change among the administration, the movement

took its most drastic measure. Approximately fifty students occupied

the office of the president and university administrators in 2001 for a

three-week sit-in. While students were in the office of the president,

supporters would sleep outside the building to show solidarity. At the

end of the sit-in, dining hall workers were able to agree on a contract

to raise the pay of workers. After the sit-in, The Living Wage Campaign

sparked unions, contract and service workers to begin negotiating for

fair wages.

Miami University

The Miami University

Living Wage Campaign began after it became known that Miami University

wage was 18-19% below the market value. In 2003 the members of the Miami

University Fair Labor Coalition began marching for university staff

wages. After negotiations failed between the university and the American Federation of State and County Municipal Employees

(AFSCME), workers went on strike. For two weeks workers protested and

students created a tent city as a way of showing support for the

strikers. Eventually more students, faculty and community members came

out to show support. Even the union president at the time also went on a

hunger strike as another means of protesting wages. In late 2003 the

union was able to make an agreement with the university for gradual

raises totaling about 10.25%. There was still an ongoing push for Miami

University to adopt a living wage policy.

Johns Hopkins University

Living wage protest and march in New York City (2015)

The Student Labor Action Committee (SLAC) of Johns Hopkins University

took action by conducting a sit-in until the administration listen to

their demands. In 1999, after a petition with thousands of signatures,

Johns Hopkins University president, William R. Brody raised the hourly

wage (to only $7.75) but did not include healthcare benefits nor would

the wage adjust for inflation. The sit-in began in early 2000 to meet

the demands of students for the university to adopt a living wage. A few

weeks later, a settlement was made with the administration. SLAC now

just ensures that the living wage policy is implemented.

Swarthmore College

Starting in 2000, the Living Wage and Democracy Campaign of Swarthmore College

began as small meetings between students and staff to voice concerns

about their wages. Over the next two years the Living Wage and Democracy

Campaign voiced concerns to the university administration. As a

response in 2002, the wage was increased from $6.66 to $9 an hour. While

the campaigners were pleased with this first result, they believed the

college still had a long way to go. The college president, Al Bloom

created the Ad Hoc Committee to help learn what the living wage was and

released a committee report. In the report suggested an hourly wage,

childcare benefit, health coverage for employees and families.

University of Virginia

The Living Wage Campaign at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia,

composed of University students, faculty, staff, and community members,

began in 1995 during the administration of University President John Casteen and continues under the administration of President Teresa Sullivan.

The campaign has demanded that the university raise wages to meet basic

standards of cost-of-living in the Charlottesville area, as calculated

by the nonpartisan Economic Policy Institute.

In 2000, the campaign succeeded in persuading university

administrators to raise the wage floor from $6.10 to $8.19; however,

this wage only applied to direct employees, not contracted workers.

In the spring of 2006, the campaign garnered national media attention

when 17 students staged a sit-in in the university president's office in

Madison Hall. A professor was arrested on the first day of the protest.

The 17 students were arrested after 4 days of protest and later

acquitted at trial.

Beginning in 2010, the campaign has staged a series of rallies

and other events to draw attention to the necessity of the living wage

for UVA employees. They have also met with members of the administration

numerous times, including with the president.

In making the argument for a living wage, the campaign has claimed that

continuing to pay low wages is inconsistent with the University's

values of the "Community of Trust." They have also noted that University President Sullivan's 2011 co-written textbook, The Social Organization of Work, states that, "Being paid a living wage for one's work is a necessary condition for self-actualization."

After rallies and meetings in the spring of 2011, President Sullivan

posted a "Commitment to Lowest-Paid Employees" on the University

President's website including a letter addressed to the Campaign.

On February 8, 2012, the Campaign released a series of demands to

University administrators calling for a living wage policy at the

University. These demands included a requirement that the University

"explicitly address" the issue by Feb. 17. Although University President

Teresa Sullivan did respond to the demands in a mass email sent to the

University community shortly before the end of the day on February 17,

the Campaign criticized her response as "intentionally misleading" and

vowed to take action.

On February 18, the campaign announced that 12 students would begin a hunger strike to publicize the plight of low-paid workers.

Criticism

Criticisms against the implementation living wage laws have taken similar forms to those against minimum wage. Economically, both can be analyzed as a price floor for labor. A price floor, if above the equilibrium price and thus effective, necessarily leads to a “surplus”. In the context of a labor market,

this means that unemployment goes up as the number of employers willing

to hire people at a “living wage” is below the number they would be

willing to hire at the equilibrium wage price. As such, setting the

minimum wage at a living wage has been criticized for possibly

destroying jobs.

Critics have warned of not just an increase in unemployment but

also price increases and a lack of entry level jobs due to ‘labor

substitutions effects’.

The voluntary undertaking of a living wage is criticized as impossible

due to the competitive advantage other businesses in the same market

would have over the one adopting a living wage. The economic argument would be that, ceteris paribus

(all other things being equal), a company that paid its workers more

than required by the market would be unable to compete with those that

pay according to market rates. This criticism ignores possible benefits that

come out of higher wages that include: higher efficiency and production

gains due to reduced absenteeism and a reduction in recruitment,

training and supervision costs.

Another issue that has emerged is that living wages may be a less

effective anti-poverty tool than other measures. Authors point to

living wages as being only a limited way of addressing the problems of

rising economic inequality, the increase of long-term low-wage jobs, and a decline of unions and legal protection for workers. Since living wage ordinances attempt to address the issue of a living wage, defined by some of its proponents as a family wage, rather than as an individual

wage, many of the beneficiaries may already be in families that make

substantially more than that necessary to provide an adequate standard

of living. According to a survey of labor economists by the Employment

Policies Institute in 2000, only 31% viewed living wages as a very or

somewhat effective anti-poverty tool, while 98% viewed policies like the

US earned income tax credit and general welfare grants in a similar

vein.

On the other hand, according to Zagros Madjd-Sadjadi, an economist with

the State of California's Division of Labor Statistics and Research,

the living wage may be seen by the public as preferable to other methods

because it reinforces the "work ethic" and ensures that there is

something of value produced, unlike welfare, that is often believed to

be a pure cash "gift" from the public coffers."

The concept of a living wage based on its definition as a family

wage has been criticized by some for emphasizing the role of men as

breadwinners.

However, occupations that would most benefit from a living wage,

including cleaning, catering, childcare, care for the elderly and the

sick, and routine office jobs, are disproportionately affected by low

pay and disproportionately staffed by women.