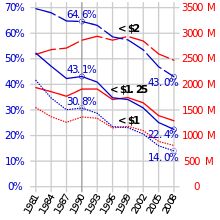

Graph

of global population living on under 1, 1.25 and 2 equivalent of 2005

US dollars daily (red) and as a proportion of world population (blue)

based on 1981–2008 World Bank data

The poverty threshold, poverty limit or poverty line is the minimum level of income deemed adequate in a particular country. In practice, like the definition of poverty, the official or common understanding of the poverty line is significantly higher in developed countries than in developing countries. In 2008, the World Bank came out with a figure (revised largely due to inflation) of $1.25 a day at 2005 purchasing-power parity (PPP). In October 2015, the World Bank updated the international poverty line

to $1.90 a day. The new figure of $1.90 is based on ICP purchasing

power parity (PPP) calculations and represents the international

equivalent of what $1.90 could buy in the US in 2011. The new IPL

replaces the $1.25 per day figure, which used 2005 data. Most scholars agree that it better reflects today's reality, particularly new price levels in developing countries. The common international poverty line has in the past been roughly $1 a day.

At present the percentage of the global population living under extreme

poverty is likely to fall below 10% according to the World Bank

projections released in 2015, although this figure is claimed by

scholars to be artificially low due to the effective reduction of the

IPL in 2015.

Determining the poverty line is usually done by finding the total

cost of all the essential resources that an average human adult

consumes in one year. The largest of these expenses is typically the rent

required to live in an apartment, so historically, economists have paid

particular attention to the real estate market and housing prices as a

strong poverty line affector. Individual factors are often used to

account for various circumstances, such as whether one is a parent,

elderly, a child, married, etc. The poverty threshold may be adjusted

annually.

History

Charles Booth, a pioneering investigator of poverty in London at the turn of the 20th century, popularised the idea of a poverty line, a concept originally conceived by the London School Board.

Booth set the line at 10 (50p) to 20 shillings (£1) per week, which he

considered to be the minimum amount necessary for a family of four or

five people to subsist on. Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree (1871–1954), a British sociological researcher, social reformer and industrialist, surveyed rich families in York,

and drew a poverty line in terms of a minimum weekly sum of money

"necessary to enable families … to secure the necessaries of a healthy

life", which included fuel and light, rent, food, clothing, and

household and personal items. Based on data from leading nutritionists of the period, he calculated the cheapest price for the minimum calorific

intake and nutritional balance necessary, before people get ill or lose

weight. He considered this amount to set his poverty line and concluded

that 27.84% of the total population of York lived below this poverty

line.

This result corresponded with that from Charles Booth's study of

poverty in London and so challenged the view, commonly held at the time,

that abject poverty was a problem particular to London and was not

widespread in the rest of Britain. Rowntree distinguished between primary poverty, those lacking in income and secondary poverty, those who had enough income, but spent it elsewhere (1901:295–96).

Absolute poverty

The term "absolute poverty" is also sometimes used as a synonym for extreme poverty. Absolute poverty is the absence of enough resources to secure basic life necessities.

According to a UN declaration that resulted from the World Summit on Social Development

in Copenhagen in 1995, absolute poverty is "a condition characterised

by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe

drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education, and

information. It depends not only on income, but also on access to

services."

David Gordon's paper, "Indicators of Poverty and Hunger", for the

United Nations, further defines absolute poverty as the absence of any

two of the following eight basic needs:

- Food: Body mass index must be above 16.

- Safe drinking water: Water must not come solely from rivers and ponds, and must be available nearby (fewer than 15 minutes' walk each way).

- Sanitation facilities: Toilets or latrines must be accessible in or near the home.

- Health: Treatment must be received for serious illnesses and pregnancy.

- Shelter: Homes must have fewer than four people living in each room. Floors must not be made of soil, mud, or clay.

- Education: Everyone must attend school or otherwise learn to read.

- Information: Everyone must have access to newspapers, radios, televisions, computers, or telephones at home.

- Access to services: This item is undefined by Gordon, but normally is used to indicate the complete panoply of education, health, legal, social, and financial (credit) services.

Basic needs

The basic needs approach is one of the major approaches to the measurement of absolute poverty in developing countries. It attempts to define the absolute minimum resources necessary for long-term physical well-being, usually in terms of consumption goods. The poverty line is then defined as the amount of income

required to satisfy those needs. The 'basic needs' approach was

introduced by the International Labour Organization's World Employment

Conference in 1976.

"Perhaps the high point of the WEP was the World Employment Conference

of 1976, which proposed the satisfaction of basic human needs as the

overiding objective of national and international development policy.

The basic needs approach to development was endorsed by governments and

workers' and employers' organizations from all over the world. It

influenced the programmes and policies of major multilateral and

bilateral development agencies, and was the precursor to the human

development approach."

A traditional list of immediate "basic needs" is food (including water), shelter, and clothing.

Many modern lists emphasize the minimum level of consumption of 'basic

needs' of not just food, water, and shelter, but also sanitation,

education, and health care. Different agencies use different lists.

In 1978, Ghai investigated the literature that criticized the

basic needs approach. Critics argued that the basic needs approach

lacked scientific rigour; it was consumption-oriented and antigrowth.

Some considered it to be "a recipe for perpetuating economic

backwardness" and for giving the impression "that poverty elimination is

all too easy". Amartya Sen focused on 'capabilities' rather than consumption.

In the development discourse, the basic needs model focuses on the measurement of what is believed to be an eradicable level of poverty.

Relative poverty

Relative poverty means low income relative to others in a country;

for example, below 60% of the median income of people in that country.

It is the "most useful measure for ascertaining poverty rates in wealthy

developed nations". Relative poverty measure is used by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and Canadian poverty researchers.[18][19][20][21][22]

In the European Union, the "relative poverty measure is the most

prominent and most–quoted of the EU social inclusion indicators."

"Relative poverty reflects better the cost of social inclusion and equality of opportunity in a specific time and space."

"Once economic development has progressed beyond a certain

minimum level, the rub of the poverty problem – from the point of view

of both the poor individual and of the societies in which they live – is

not so much the effects of poverty in any absolute form but the effects

of the contrast, daily perceived, between the lives of the poor and the

lives of those around them. For practical purposes, the problem of

poverty in the industrialized nations today is a problem of relative

poverty (page 9)."

However, some have argued that as relative poverty is merely a

measure of inequality, using the term 'poverty' for it is misleading.

For example, if everyone in a country's income doubled, it would not

reduce the amount of 'relative poverty' at all.

History of the concept of relative poverty

In 1776, Adam Smith

argued that poverty is the inability to afford "not only the

commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life,

but whatever the custom of the country renders it indecent for

creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without."

In 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith

argued, "People are poverty stricken when their income, even if

adequate for survival, falls markedly behind that of their community."

In 1964, in a joint committee economic President's report in the

United States, Republicans endorsed the concept of relative poverty: "No

objective definition of poverty exists. ... The definition varies from

place to place and time to time. In America as our standard of living

rises, so does our idea of what is substandard."

In 1965, Rose Friedman

argued for the use of relative poverty claiming that the definition of

poverty changes with general living standards. Those labelled as poor in

1995, would have had "a higher standard of living than many labelled

not poor" in 1965.

In 1979, British sociologist, Peter Townsend

published his famous definition: "individuals... can be said to be in

poverty when they lack the resources to obtain the types of diet,

participate in the activities and have the living conditions and

amenities which are customary, or are at least widely encouraged or

approved, in the societies to which they belong (page 31)."

Brian Nolan and Christopher T. Whelan of the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in Ireland explained that "poverty has to be seen in terms of the standard of living of the society in question."

Relative poverty measures are used as official poverty rates by

the European Union, UNICEF and the OEDC. The main poverty line used in

the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 60% of the median household income.

Relative poverty compared with other standards

A measure of relative poverty

defines "poverty" as being below some relative poverty threshold. For

example, the statement that "those individuals who are employed and

whose household equivalised disposable income is below 60% of national

median equivalised income are poor" uses a relative measure to define

poverty.

The term relative poverty can also be used in a different sense to mean "moderate poverty" – for example, a standard of living or level of income that is high enough to satisfy basic needs (like water, food, clothing, housing, and basic health care), but still significantly lower than that of the majority of the population under consideration.

National poverty lines

2008

CIA World Factbook-based map showing the percentage of population by

country living below that country's official poverty line

National estimates are based on population-weighted subgroup

estimates from household surveys. Definitions of the poverty line do

vary considerably among nations. For example, rich nations generally

employ more generous standards of poverty than poor nations. Even among

rich nations, the standards differ greatly. Thus, the numbers are not

comparable among countries. Even when nations do use the same method,

some issues may remain.

In United States, the poverty thresholds are updated every year

by Census Bureau. The threshold in United States are updated and used

for statistical purposes. In 2015, in the United States, the poverty

threshold for a single person under 65 was an annual income of

US$11,770; the threshold for a family group of four, including two

children, was US$24,250. According to the U.S. Census Bureau data released on 13 September 2011, the nation's poverty rate rose to 15.1 percent in 2010.

In the UK, "more than five million people – over a fifth (23

percent) of all employees – were paid less than £6.67 an hour in April

2006. This value is based on a low pay rate of 60 percent of full-time

median earnings, equivalent to a little over £12,000 a year for a

35-hour working week. In April 2006, a 35-hour week would have earned

someone £9,191 a year – before tax or National Insurance".

India's official poverty level as of 2005, on the other hand, is

split according to rural versus urban thresholds. For urban dwellers,

the poverty line is defined as living on less than 538.60 rupees

(approximately US$12) per month, whereas for rural dwellers, it is

defined as living on less than 356.35 rupees per month (approximately

US$7.50).

Wealth inequality

Poverty is impacted through wealth inequality, while the rich are getting richer the poor are losing even more.

Wealth facilitates the continuation of economic inequality, the lowest

quintile of Americans only own less than 1 percent of all wealth in

America while the top quintile owns 60 percent of the wealth.

Wealth inequality is more extreme and a larger indicator of financial

well being than income inequality, this means it impacts people in

poverty even more.

People in poverty do not have the access to resources that in the upper

quintile do, such as stocks, investments, multiple houses, stable jobs,

and better education.

Stocks are a good example of this, while 94.9 of the top 1 percent own

stocks only 20.8 percent of the bottom 20 percent of Americans own

stock. This inequality of access allows for wealth inequality to grow and continue to impact those in poverty.

Women and children

Women

and children find themselves impacted by poverty more often than men,

most specifically when apart of single mother families. This is due to the feminization of poverty, how the poverty rate of women has increasingly exceeded that of mens.

While the overall poverty rate is 12.3%, women are 13.8% likely to fall

into poverty and men are below the overall rate at 11.1%.

Most women if they fall into poverty because of the expectation that

they will be taking care of children while trying to maintain their

jobs, because of the expectation that women will be with kids they are

segregated into lower paying jobs than male counterparts. Along with being put into lower paying jobs women do more unpaid work for their children than men do. This is how the percent of single mothers has risen to 34%, much above the national rate.

Women and children (as single mother families) find themselves as apart

of low class communities because they are 21.6% more likely to fall

into poverty.

Racial minorities

Racial

minorities have been a large part of American history. A minority group

is defined as “a category of people who experience relative

disadvantage as compared to members of a dominant social group.”

Minorities are traditionally separated into the following groups:

African Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Asians, Pacific

Islanders, and Hispanics.

They must be accounted for when discussing the poverty line in the U.S.

in 2018 because the majority of America's population consists of

immigrants.

According to the current U.S. Poverty statistics, Black Americans -

21%, Foreign born non-citizens - 19%, Hispanic Americans - 18%, and

Adults with a disability - 25%.

This does not include all minority groups, but these groups alone

account for 85% of people under the poverty line in the United States. Whites have a poverty rate of 8.7%; the poverty rate is more than double for Black and Hispanic Americans.

Impacts on education

Living below the poverty threshold can have a major impact on a child’s education. The psychological stresses induced by poverty may affect a student’s ability to perform well academically. In addition, the risk of poor health is more prevalent for those living in poverty. Health issues commonly affect the extent to which one can continue and fully take advantage of his or her education. Poor students in the United States are more likely to dropout of school at some point in their education. Research has also found that children living in poverty perform poorly academically and have lower cognitive abilities. Impoverished children also display more behavioral issues than others.

Schools in impoverished communities usually do not receive much

funding, which can also set their students apart from those living in

more affluent neighborhoods.

Even upward mobility that brings a child out of poverty may not have a

significant positive impact on his or her education; inadequate academic

habits that form as early as preschool typically do not improve despite

changes in socioeconomic status.

Impacts on healthcare

The nation’s poverty threshold is issued by the Census Bureau.

According to the Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and

Evaluation the threshold is statistically relevant and can be a solid

predictor of people in poverty.

The reasoning for using Federal Poverty Level, FPL, is due to its

action for distributive purposes under the direction of Health and Human

Services. So FPL is a tool derived from the threshold but can be used

to show eligibility for certain federal programs.

Federal poverty levels have direct effects on individual’s healthcare.

In the past years and into the present government, the use of the

poverty threshold has consequences for such programs like Medicaid and

the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

The benefits which different families are eligible for are contingent

on FPL. The FPL, in turn is calculated based on federal numbers from the

previous year.

The benefits and qualifications for federal programs are dependent on

number of people on a plan and the income of the total group.

For 2019, the U.S Department of health & Human Services enumerate

what the line is for different families. For a single person, the line

is $12,490 and up to $43,430 for a family of 8, in the lower 48 states.

Another issue is reduced-cost coverage. These reductions are based on

income relative to FPL, and work in connection with public health

services such as Medicaid. The divisions of FPL percentages are nominally, above 400%, below 138% and below 100% of the FPL. After the advent of the American Care Act, Medicaid was expanded on states bases. For example, enrolling in the ACA kept the benefits of Medicaid when the income was up to 138% of the FPL.

Poverty mobility and healthcare

Health

Affairs along with analysis by Georgetown found that public assistance

does counteract poverty threats between 2010 and 2015. In regards to Medicaid, child poverty is decreased by 5.3%, and Hispanic and Black poverty by 6.1% and 4.9% respectively. The reduction of family poverty also has the highest decrease with Medicaid over other public assistance programs.

Expanding state Medicaid decreased the amount individuals paid by an

average of $42, while it increased the costs to $326 for people not in

expanded states. The same study analyzed showed 2.6 million people were

kept out of poverty by the effects of Medicaid.

From a 2013-2015 study, expansion states showed a smaller gap in health

insurance between households making below $25,000 and above $75,000.

Expansion also significantly reduced the gap of having a primary care

physician between impoverished and higher income individuals. In terms of education level and employment, health insurance differences were also reduced. Non-expansion also showed poor residents went from a 22% chance of being uninsured to 66% from 2013 to 2015.

Poverty dynamics

Living above or below the poverty threshold is not necessarily a position in which an individual remains static.

As many as one in three impoverished people were not poor at birth;

rather, they descended into poverty over the course of their life.

Additionally, a study which analyzed data from the Panel Study of

Income Dynamics (PSID) found that nearly 40% of 20-year-olds received

food stamps at some point before they turned 65.

This indicates that many Americans will dip below the poverty line

sometime during adulthood, but will not necessarily remain there for the

rest of their life.

Furthermore, 44% of individuals who are given transfer benefits (other

than Social Security) in one year do not receive them the next.

Over 90% of Americans who receive transfers from the government stop

receiving them within 10 years, indicating that the population living

below the poverty threshold is in flux and does not remain constant.

Criticisms

Using a poverty threshold is problematic because having an income

slightly above or below is not substantially different; the negative

effects of poverty tend to be continuous rather than discrete, and the

same low income affects different people in different ways. To overcome

this problem, a poverty index or indices can be used instead; see income inequality metrics.

A poverty threshold relies on a quantitative,

or purely numbers-based, measure of income. If other human

development-indicators like health and education are used, they must be

quantified, which is not a simple (if even achievable) task.

Using a single monetary poverty threshold is problematic when

applied worldwide, due to the difficulty of comparing prices between

countries. Prices of the same goods vary dramatically from country to

country; while this is typically corrected for by using purchasing power parity

(PPP) exchange rates, the basket of goods used to determine such rates

is usually unrepresentative of the poor, most of whose expenditure is on

basic foodstuffs rather than the relatively luxurious items (washing

machines, air travel, healthcare) often included in PPP baskets. The

economist Robert C. Allen

has attempted to solve this by using standardized baskets of goods

typical of those bought by the poor across countries and historical

time, for example including a fixed calorific quantity of the cheapest

local grain (such as corn, rice, or oats).

Understating poverty

In addition to wage and salary income, investment income and government transfers such as SNAP

(Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps)

and housing subsidies are included in a household's income. Studies

measuring the differences between income before and after taxes and

government transfers, have found that without social support programs,

poverty would be roughly 30% to 40% higher than the official poverty

line indicates.

Further, the U.S. Census Bureau calculates the poverty line the

same throughout the U.S. regardless of the cost-of-living in a state or

urban area. For instance, the cost-of-living in California, the most

populous state, was 42% greater than the U.S. average in 2010, while the

cost-of-living in Texas, the second-most populous state, was 10% less

than the U.S. average.

In 2017, California had the highest poverty rate in the country when

housing costs are factored in, a measure calculated by the Census Bureau

known as "the supplemental poverty measure".