An embedded system on a plug-in card with processor, memory, power supply, and external interfaces

An embedded system is a computer system—a combination of a computer processor, computer memory, and input/output peripheral devices—that has a dedicated function within a larger mechanical or electrical system. It is embedded as part of a complete device often including electrical or electronic hardware and mechanical parts.

Because an embedded system typically controls physical operations of the machine that it is embedded within, it often has real-time computing constraints. Embedded systems control many devices in common use today. Ninety-eight percent of all microprocessors manufactured are used in embedded systems.

Modern embedded systems are often based on microcontrollers

(i.e. microprocessors with integrated memory and peripheral

interfaces), but ordinary microprocessors (using external chips for

memory and peripheral interface circuits) are also common, especially in

more complex systems. In either case, the processor(s) used may be

types ranging from general purpose to those specialized in certain class

of computations, or even custom designed for the application at hand. A

common standard class of dedicated processors is the digital signal processor

(DSP).

Since the embedded system is dedicated to specific tasks, design

engineers can optimize it to reduce the size and cost of the product and

increase the reliability and performance. Some embedded systems are

mass-produced, benefiting from economies of scale.

Embedded systems range from portable devices such as digital watches and MP3 players, to large stationary installations like traffic light controllers, programmable logic controllers, and large complex systems like hybrid vehicles, medical imaging systems, and avionics. Complexity varies from low, with a single microcontroller chip, to very high with multiple units, peripherals and networks mounted inside a large equipment rack.

History

Background

The origins of the microprocessor and the microcontroller can be traced back to the MOS integrated circuit, which is an integrated circuit chip fabricated from MOSFETs

(metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors) and was developed

in the early 1960s. By 1964, MOS chips had reached higher transistor density and lower manufacturing costs than bipolar chips. MOS chips further increased in complexity at a rate predicted by Moore's law, leading to large-scale integration (LSI) with hundreds of transistors on a single MOS chip by the late 1960s. The application of MOS LSI chips to computing was the basis for the first microprocessors, as engineers began recognizing that a complete computer processor system could be contained on several MOS LSI chips.

The first multi-chip microprocessors, the Four-Phase Systems AL1 in 1969 and the Garrett AiResearch MP944 in 1970, were developed with multiple MOS LSI chips. The first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004, released in 1971. It was developed by Federico Faggin, using his silicon-gate MOS technology, along with Intel engineers Marcian Hoff and Stan Mazor, and Busicom engineer Masatoshi Shima.

Development

One of the very first recognizably modern embedded systems was the Apollo Guidance Computer, developed ca. 1965 by Charles Stark Draper at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory.

At the project's inception, the Apollo guidance computer was considered

the riskiest item in the Apollo project as it employed the then newly

developed monolithic integrated circuits to reduce the size and weight. An early mass-produced embedded system was the Autonetics D-17 guidance computer for the Minuteman missile,

released in 1961. When the Minuteman II went into production in 1966,

the D-17 was replaced with a new computer that was the first high-volume

use of integrated circuits.

Since these early applications in the 1960s, embedded systems

have come down in price and there has been a dramatic rise in processing

power and functionality. An early microprocessor for example, the Intel 4004 (released in 1971), was designed for calculators

and other small systems but still required external memory and support

chips. In 1978 National Engineering Manufacturers Association released a

"standard" for programmable microcontrollers, including almost any

computer-based controllers, such as single board computers, numerical,

and event-based controllers.

As the cost of microprocessors and microcontrollers fell it became feasible to replace expensive knob-based analog components such as potentiometers and variable capacitors

with up/down buttons or knobs read out by a microprocessor even in

consumer products. By the early 1980s, memory, input and output system

components had been integrated into the same chip as the processor

forming a microcontroller. Microcontrollers find applications where a general-purpose computer would be too costly.

A comparatively low-cost microcontroller may be programmed to

fulfill the same role as a large number of separate components. Although

in this context an embedded system is usually more complex than a

traditional solution, most of the complexity is contained within the

microcontroller itself. Very few additional components may be needed and

most of the design effort is in the software. Software prototype and

test can be quicker compared with the design and construction of a new

circuit not using an embedded processor.

Applications

Embedded Computer Sub-Assembly for Accupoll Electronic Voting Machine

Embedded systems are commonly found in consumer, industrial,

automotive, home appliances, medical, commercial and military

applications.

Telecommunications systems employ numerous embedded systems from telephone switches for the network to cell phones at the end user.

Computer networking uses dedicated routers and network bridges to route data.

Consumer electronics include MP3 players, mobile phones, video game consoles, digital cameras, GPS receivers, and printers.

Household appliances, such as microwave ovens, washing machines and dishwashers, include embedded systems to provide flexibility, efficiency and features. Advanced HVAC systems use networked thermostats to more accurately and efficiently control temperature that can change by time of day and season. Home automation

uses wired- and wireless-networking that can be used to control lights,

climate, security, audio/visual, surveillance, etc., all of which use

embedded devices for sensing and controlling.

Transportation systems from flight to automobiles increasingly use embedded systems.

New airplanes contain advanced avionics such as inertial guidance systems and GPS receivers that also have considerable safety requirements.

Various electric motors — brushless DC motors, induction motors and DC motors — use electric/electronic motor controllers.

Automobiles, electric vehicles, and hybrid vehicles increasingly use embedded systems to maximize efficiency and reduce pollution.

Other automotive safety systems include anti-lock braking system (ABS), Electronic Stability Control (ESC/ESP), traction control (TCS) and automatic four-wheel drive.

Medical equipment uses embedded systems for vital signs monitoring, electronic stethoscopes for amplifying sounds, and various medical imaging (PET, SPECT, CT, and MRI) for non-invasive internal inspections. Embedded systems within medical equipment are often powered by industrial computers.

Embedded systems are used in transportation, fire safety, safety

and security, medical applications and life critical systems, as these

systems can be isolated from hacking and thus, be more reliable, unless

connected to wired or wireless networks via on-chip 3G cellular or other

methods for IoT monitoring and control purposes.

For fire safety, the systems can be designed to have greater ability to

handle higher temperatures and continue to operate. In dealing with

security, the embedded systems can be self-sufficient and be able to

deal with cut electrical and communication systems.

A new class of miniature wireless devices called motes are networked wireless sensors. Wireless sensor networking, WSN,

makes use of miniaturization made possible by advanced IC design to

couple full wireless subsystems to sophisticated sensors, enabling

people and companies to measure a myriad of things in the physical world

and act on this information through IT monitoring and control systems.

These motes are completely self-contained, and will typically run off a

battery source for years before the batteries need to be changed or

charged.

Embedded Wi-Fi modules provide a simple means of wirelessly enabling any device that communicates via a serial port.

Characteristics

Embedded

systems are designed to do some specific task, rather than be a

general-purpose computer for multiple tasks. Some also have real-time

performance constraints that must be met, for reasons such as safety

and usability; others may have low or no performance requirements,

allowing the system hardware to be simplified to reduce costs.

Embedded systems are not always standalone devices. Many embedded

systems consist of small parts within a larger device that serves a

more general purpose. For example, the Gibson Robot Guitar features an embedded system for tuning the strings, but the overall purpose of the Robot Guitar is, of course, to play music. Similarly, an embedded system in an automobile provides a specific function as a subsystem of the car itself.

e-con Systems eSOM270 & eSOM300 Computer on Modules

The program instructions written for embedded systems are referred to as firmware, and are stored in read-only memory or flash memory chips. They run with limited computer hardware resources: little memory, small or non-existent keyboard or screen.

User interface

Embedded system text user interface using MicroVGA

Embedded systems range from no user interface at all, in systems dedicated only to one task, to complex graphical user interfaces that resemble modern computer desktop operating systems.

Simple embedded devices use buttons, LEDs, graphic or character LCDs (HD44780 LCD for example) with a simple menu system.

More sophisticated devices that use a graphical screen with touch

sensing or screen-edge buttons provide flexibility while minimizing

space used: the meaning of the buttons can change with the screen, and

selection involves the natural behavior of pointing at what is desired. Handheld systems often have a screen with a "joystick button" for a pointing device.

Some systems provide user interface remotely with the help of a serial (e.g. RS-232, USB, I²C, etc.) or network (e.g. Ethernet)

connection. This approach gives several advantages: extends the

capabilities of embedded system, avoids the cost of a display,

simplifies BSP and allows one to build a rich user interface on the PC. A good example of this is the combination of an embedded web server running on an embedded device (such as an IP camera) or a network router. The user interface is displayed in a web browser on a PC connected to the device, therefore needing no software to be installed.

Processors in embedded systems

Examples

of properties of typical embedded computers when compared with

general-purpose counterparts are low power consumption, small size,

rugged operating ranges, and low per-unit cost. This comes at the price

of limited processing resources, which make them significantly more

difficult to program and to interact with. However, by building

intelligence mechanisms on top of the hardware, taking advantage of

possible existing sensors and the existence of a network of embedded

units, one can both optimally manage available resources at the unit and

network levels as well as provide augmented functions, well beyond

those available. For example, intelligent techniques can be designed to manage power consumption of embedded systems.

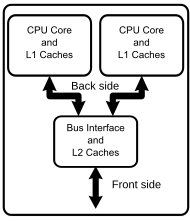

Embedded processors can be broken into two broad categories.

Ordinary microprocessors (μP) use separate integrated circuits for

memory and peripherals. Microcontrollers (μC) have on-chip peripherals,

thus reducing power consumption, size and cost. In contrast to the

personal computer market, many different basic CPU architectures are used since software is custom-developed for an application and is not a commodity product installed by the end user. Both Von Neumann as well as various degrees of Harvard architectures are used. RISC

as well as non-RISC processors are found. Word lengths vary from 4-bit

to 64-bits and beyond, although the most typical remain 8/16-bit. Most

architectures come in a large number of different variants and shapes,

many of which are also manufactured by several different companies.

Numerous microcontrollers

have been developed for embedded systems use. General-purpose

microprocessors are also used in embedded systems, but generally,

require more support circuitry than microcontrollers.

Ready-made computer boards

PC/104 and PC/104+ are examples of standards for ready-made

computer boards intended for small, low-volume embedded and ruggedized

systems, mostly x86-based. These are often physically small compared to a

standard PC, although still quite large compared to most simple

(8/16-bit) embedded systems. They often use DOS, Linux, NetBSD, or an embedded real-time operating system such as MicroC/OS-II, QNX or VxWorks. Sometimes these boards use non-x86 processors.

In certain applications, where small size or power efficiency are

not primary concerns, the components used may be compatible with those

used in general purpose x86 personal computers. Boards such as the VIA EPIA

range help to bridge the gap by being PC-compatible but highly

integrated, physically smaller or have other attributes making them

attractive to embedded engineers. The advantage of this approach is that

low-cost commodity components may be used along with the same software

development tools used for general software development. Systems built

in this way are still regarded as embedded since they are integrated

into larger devices and fulfill a single role. Examples of devices that

may adopt this approach are ATMs and arcade machines, which contain code specific to the application.

However, most ready-made embedded systems boards are not PC-centered and do not use the ISA or PCI buses. When a system-on-a-chip

processor is involved, there may be little benefit to having a

standardized bus connecting discrete components, and the environment for

both hardware and software tools may be very different.

One common design style uses a small system module, perhaps the size of a business card, holding high density BGA chips such as an ARM-based system-on-a-chip processor and peripherals, external flash memory for storage, and DRAM

for runtime memory. The module vendor will usually provide boot

software and make sure there is a selection of operating systems,

usually including Linux

and some real time choices. These modules can be manufactured in high

volume, by organizations familiar with their specialized testing issues,

and combined with much lower volume custom mainboards with

application-specific external peripherals.

Implementation of embedded systems has advanced so that they can

easily be implemented with already-made boards that are based on

worldwide accepted platforms. These platforms include, but are not

limited to, Arduino and Raspberry Pi.

ASIC and FPGA solutions

A common array for very-high-volume embedded systems is the system on a chip

(SoC) that contains a complete system consisting of multiple

processors, multipliers, caches and interfaces on a single chip. SoCs

can be implemented as an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) or using a field-programmable gate array (FPGA).

Peripherals

A close-up of the SMSC LAN91C110 (SMSC 91x) chip, an embedded Ethernet chip

Embedded systems talk with the outside world via peripherals, such as:

- Serial Communication Interfaces (SCI): RS-232, RS-422, RS-485, etc.

- Synchronous Serial Communication Interface: I2C, SPI, SSC and ESSI (Enhanced Synchronous Serial Interface)

- Universal Serial Bus (USB)

- Multi Media Cards (SD cards, Compact Flash, etc.)

- Networks: Ethernet, LonWorks, etc.

- Fieldbuses: CAN-Bus, LIN-Bus, PROFIBUS, etc.

- Timers: PLL(s), Capture/Compare and Time Processing Units

- Discrete IO: aka General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO)

- Analog to Digital/Digital to Analog (ADC/DAC)

- Debugging: JTAG, ISP, BDM Port, BITP, and DB9 ports.

Tools

As with other software, embedded system designers use compilers, assemblers, and debuggers to develop embedded system software. However, they may also use some more specific tools:

- In circuit debuggers or emulators (see next section).

- Utilities to add a checksum or CRC to a program, so the embedded system can check if the program is valid.

- For systems using digital signal processing, developers may use a math workbench to simulate the mathematics.

- System level modeling and simulation tools help designers to construct simulation models of a system with hardware components such as processors, memories, DMA, interfaces, buses and software behavior flow as a state diagram or flow diagram using configurable library blocks. Simulation is conducted to select right components by performing power vs. performance trade-off, reliability analysis and bottleneck analysis. Typical reports that helps designer to make architecture decisions includes application latency, device throughput, device utilization, power consumption of the full system as well as device-level power consumption.

- A model-based development tool creates and simulate graphical data flow and UML state chart diagrams of components like digital filters, motor controllers, communication protocol decoding and multi-rate tasks.

- Custom compilers and linkers may be used to optimize specialized hardware.

- An embedded system may have its own special language or design tool, or add enhancements to an existing language such as Forth or Basic.

- Another alternative is to add a real-time operating system or embedded operating system

- Modeling and code generating tools often based on state machines

Software tools can come from several sources:

- Software companies that specialize in the embedded market

- Ported from the GNU software development tools

- Sometimes, development tools for a personal computer can be used if the embedded processor is a close relative to a common PC processor

As the complexity of embedded systems grows, higher level tools and

operating systems are migrating into machinery where it makes sense. For

example, cellphones, personal digital assistants

and other consumer computers often need significant software that is

purchased or provided by a person other than the manufacturer of the

electronics. In these systems, an open programming environment such as Linux, NetBSD, OSGi or Embedded Java is required so that the third-party software provider can sell to a large market.

Embedded systems are commonly found in consumer, cooking,

industrial, automotive, medical applications.

Some examples of embedded systems are MP3 players, mobile phones, video

game consoles, digital cameras, DVD players, and GPS. Household

appliances, such as microwave ovens, washing machines and dishwashers,

include embedded systems to provide flexibility and efficiency.

Debugging

Embedded debugging

may be performed at different levels, depending on the facilities

available. The different metrics that characterize the different forms

of embedded debugging are: does it slow down the main application, how

close is the debugged system or application to the actual system or

application, how expressive are the triggers that can be set for

debugging (e.g., inspecting the memory when a particular program counter value is reached), and what can be inspected in the debugging process (such as, only memory, or memory and registers, etc.).

From simplest to most sophisticated they can be roughly grouped into the following areas:

- Interactive resident debugging, using the simple shell provided by the embedded operating system (e.g. Forth and Basic)

- External debugging using logging or serial port output to trace operation using either a monitor in flash or using a debug server like the Remedy Debugger that even works for heterogeneous multicore systems.

- An in-circuit debugger (ICD), a hardware device that connects to the microprocessor via a JTAG or Nexus interface. This allows the operation of the microprocessor to be controlled externally, but is typically restricted to specific debugging capabilities in the processor.

- An in-circuit emulator (ICE) replaces the microprocessor with a simulated equivalent, providing full control over all aspects of the microprocessor.

- A complete emulator provides a simulation of all aspects of the hardware, allowing all of it to be controlled and modified, and allowing debugging on a normal PC. The downsides are expense and slow operation, in some cases up to 100 times slower than the final system.

- For SoC designs, the typical approach is to verify and debug the design on an FPGA prototype board. Tools such as Certus are used to insert probes in the FPGA RTL that make signals available for observation. This is used to debug hardware, firmware and software interactions across multiple FPGA with capabilities similar to a logic analyzer.

- Software-only debuggers have the benefit that they do not need any hardware modification but have to carefully control what they record in order to conserve time and storage space.

Unless restricted to external debugging, the programmer can typically

load and run software through the tools, view the code running in the

processor, and start or stop its operation. The view of the code may be

as HLL source-code, assembly code or mixture of both.

Because an embedded system is often composed of a wide variety of

elements, the debugging strategy may vary. For instance, debugging a

software- (and microprocessor-) centric embedded system is different

from debugging an embedded system where most of the processing is

performed by peripherals (DSP, FPGA, and co-processor).

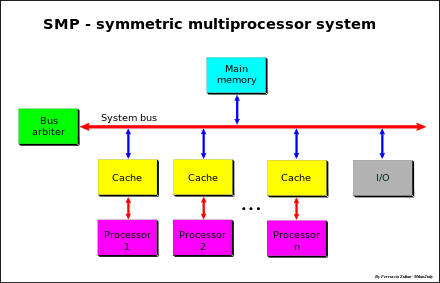

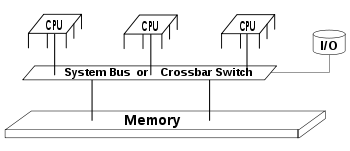

An increasing number of embedded systems today use more than one single

processor core. A common problem with multi-core development is the

proper synchronization of software execution. In this case, the embedded

system design may wish to check the data traffic on the buses between

the processor cores, which requires very low-level debugging, at

signal/bus level, with a logic analyzer, for instance.

Tracing

Real-time operating systems (RTOS) often supports tracing

of operating system events. A graphical view is presented by a host PC

tool, based on a recording of the system behavior. The trace recording

can be performed in software, by the RTOS, or by special tracing

hardware. RTOS tracing allows developers to understand timing and

performance issues of the software system and gives a good understanding

of the high-level system behaviors.

Reliability

Embedded

systems often reside in machines that are expected to run continuously

for years without errors, and in some cases recover by themselves if an

error occurs. Therefore, the software is usually developed and tested

more carefully than that for personal computers, and unreliable

mechanical moving parts such as disk drives, switches or buttons are

avoided.

Specific reliability issues may include:

- The system cannot safely be shut down for repair, or it is too inaccessible to repair. Examples include space systems, undersea cables, navigational beacons, bore-hole systems, and automobiles.

- The system must be kept running for safety reasons. "Limp modes" are less tolerable. Often backups are selected by an operator. Examples include aircraft navigation, reactor control systems, safety-critical chemical factory controls, train signals.

- The system will lose large amounts of money when shut down: Telephone switches, factory controls, bridge and elevator controls, funds transfer and market making, automated sales and service.

A variety of techniques are used, sometimes in combination, to recover from errors—both software bugs such as memory leaks, and also soft errors in the hardware:

- watchdog timer that resets the computer unless the software periodically notifies the watchdog subsystems with redundant spares that can be switched over to software "limp modes" that provide partial function

- Designing with a Trusted Computing Base (TCB) architecture ensures a highly secure & reliable system environment

- A hypervisor designed for embedded systems, is able to provide secure encapsulation for any subsystem component, so that a compromised software component cannot interfere with other subsystems, or privileged-level system software. This encapsulation keeps faults from propagating from one subsystem to another, thereby improving reliability. This may also allow a subsystem to be automatically shut down and restarted on fault detection.

- Immunity Aware Programming

High vs. low volume

For high volume systems such as portable music players or mobile phones,

minimizing cost is usually the primary design consideration. Engineers

typically select hardware that is just “good enough” to implement the

necessary functions.

For low-volume or prototype embedded systems, general purpose

computers may be adapted by limiting the programs or by replacing the

operating system with a real-time operating system.

Embedded software architectures

There are several different types of software architecture in common use.

Simple control loop

In this design, the software simply has a loop. The loop calls subroutines, each of which manages a part of the hardware or software. Hence it is called a simple control loop or control loop.

Interrupt-controlled system

Some embedded systems are predominantly controlled by interrupts.

This means that tasks performed by the system are triggered by

different kinds of events; an interrupt could be generated, for example,

by a timer in a predefined frequency, or by a serial port controller

receiving a byte.

These kinds of systems are used if event handlers need low

latency, and the event handlers are short and simple. Usually, these

kinds of systems run a simple task in a main loop also, but this task is

not very sensitive to unexpected delays.

Sometimes the interrupt handler will add longer tasks to a queue

structure. Later, after the interrupt handler has finished, these tasks

are executed by the main loop. This method brings the system close to a

multitasking kernel with discrete processes.

Cooperative multitasking

A nonpreemptive multitasking system is very similar to the simple control loop scheme, except that the loop is hidden in an API.

The programmer defines a series of tasks, and each task gets its own

environment to “run” in. When a task is idle, it calls an idle routine,

usually called “pause”, “wait”, “yield”, “nop” (stands for no operation), etc.

The advantages and disadvantages are similar to that of the

control loop, except that adding new software is easier, by simply

writing a new task, or adding to the queue.

Preemptive multitasking or multi-threading

In

this type of system, a low-level piece of code switches between tasks

or threads based on a timer (connected to an interrupt). This is the

level at which the system is generally considered to have an "operating

system" kernel. Depending on how much functionality is required, it

introduces more or less of the complexities of managing multiple tasks

running conceptually in parallel.

As any code can potentially damage the data of another task (except in larger systems using an MMU)

programs must be carefully designed and tested, and access to shared

data must be controlled by some synchronization strategy, such as message queues, semaphores or a non-blocking synchronization scheme.

Because of these complexities, it is common for organizations to use a real-time operating system

(RTOS), allowing the application programmers to concentrate on device

functionality rather than operating system services, at least for large

systems; smaller systems often cannot afford the overhead associated

with a generic real-time system, due to limitations regarding

memory size, performance, or battery life. The choice that an RTOS is

required brings in its own issues, however, as the selection must be

done prior to starting to the application development process. This

timing forces developers to choose the embedded operating system for

their device based upon current requirements and so restricts future

options to a large extent.

The restriction of future options becomes more of an issue as product

life decreases. Additionally the level of complexity is continuously

growing as devices are required to manage variables such as serial, USB,

TCP/IP, Bluetooth, Wireless LAN, trunk radio, multiple channels, data

and voice, enhanced graphics, multiple states, multiple threads,

numerous wait states and so on. These trends are leading to the uptake

of embedded middleware in addition to a real-time operating system.

Microkernels and exokernels

A microkernel

is a logical step up from a real-time OS. The usual arrangement is that

the operating system kernel allocates memory and switches the CPU to

different threads of execution. User mode processes implement major

functions such as file systems, network interfaces, etc.

In general, microkernels succeed when the task switching and intertask communication is fast and fail when they are slow.

Exokernels

communicate efficiently by normal subroutine calls. The hardware and

all the software in the system are available to and extensible by

application programmers.

Monolithic kernels

In

this case, a relatively large kernel with sophisticated capabilities is

adapted to suit an embedded environment. This gives programmers an

environment similar to a desktop operating system like Linux or Microsoft Windows,

and is therefore very productive for development; on the downside, it

requires considerably more hardware resources, is often more expensive,

and, because of the complexity of these kernels, can be less predictable

and reliable.

Despite the increased cost in hardware, this type of embedded

system is increasing in popularity, especially on the more powerful

embedded devices such as wireless routers and GPS navigation systems. Here are some of the reasons:

- Ports to common embedded chip sets are available.

- They permit re-use of publicly available code for device drivers, web servers, firewalls, and other code.

- Development systems can start out with broad feature-sets, and then the distribution can be configured to exclude unneeded functionality, and save the expense of the memory that it would consume.

- Many engineers believe that running application code in user mode is more reliable and easier to debug, thus making the development process easier and the code more portable.[citation needed]

- Features requiring faster response than can be guaranteed can often be placed in hardware.

Additional software components

In

addition to the core operating system, many embedded systems have

additional upper-layer software components. These components consist of

networking protocol stacks like CAN, TCP/IP, FTP, HTTP, and HTTPS, and also included storage capabilities like FAT

and flash memory management systems. If the embedded device has audio

and video capabilities, then the appropriate drivers and codecs will be

present in the system. In the case of the monolithic kernels, many of

these software layers are included. In the RTOS category, the

availability of the additional software components depends upon the

commercial offering.

Domain-specific architectures

In the automotive sector, AUTOSAR is a standard architecture for embedded software.