For many immigrants, the Statue of Liberty

was their first view of the United States. It signified new

opportunities in life and thus the statue is an iconic symbol of the

American Dream.

The American Dream is a national ethos of the United States,

the set of ideals (democracy, rights, liberty, opportunity and

equality) in which freedom includes the opportunity for prosperity and

success, as well as an upward social mobility

for the family and children, achieved through hard work in a society

with few barriers. In the definition of the American Dream by James Truslow Adams

in 1931, "life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone,

with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement"

regardless of social class or circumstances of birth.

The American Dream is rooted in the Declaration of Independence, which proclaims that "all men are created equal" with the right to "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Also, the U.S. Constitution promotes similar freedom, in the Preamble: to "secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity".

History

The meaning of the "American Dream" has changed over the course of

history, and includes both personal components (such as home ownership

and upward mobility) and a global vision. Historically the Dream

originated in the mystique regarding frontier life.

As the Governor of Virginia noted in 1774, the Americans "for ever

imagine the Lands further off are still better than those upon which

they are already settled". He added that, "if they attained Paradise,

they would move on if they heard of a better place farther west".

19th century

In the 19th century, many well-educated Germans fled the failed 1848 revolution.

They welcomed the political freedoms in the New World, and the lack of a

hierarchical or aristocratic society that determined the ceiling for

individual aspirations. One of them explained:

The German emigrant comes into a country free from the despotism, privileged orders and monopolies, intolerable taxes, and constraints in matters of belief and conscience. Everyone can travel and settle wherever he pleases. No passport is demanded, no police mingles in his affairs or hinders his movements ... Fidelity and merit are the only sources of honor here. The rich stand on the same footing as the poor; the scholar is not a mug above the most humble mechanics; no German ought to be ashamed to pursue any occupation ... [In America] wealth and possession of real estate confer not the least political right on its owner above what the poorest citizen has. Nor are there nobility, privileged orders, or standing armies to weaken the physical and moral power of the people, nor are there swarms of public functionaries to devour in idleness credit for. Above all, there are no princes and corrupt courts representing the so-called divine 'right of birth.' In such a country the talents, energy and perseverance of a person ... have far greater opportunity to display than in monarchies.

The discovery of gold in California in 1849 brought in a hundred thousand men looking for their fortune overnight—and a few did find it. Thus was born the California Dream of instant success. Historian H. W. Brands noted that in the years after the Gold Rush, the California Dream spread across the nation:

The old American Dream ... was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin's "Poor Richard"... of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream ... became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter's Mill."

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 advanced the Frontier Thesis, under which American democracy

and the American Dream were formed by the American frontier. He

stressed the process—the moving frontier line—and the impact it had on pioneers going through the process. He also stressed results; especially that American democracy was the primary result, along with egalitarianism, a lack of interest in high culture, and violence. "American democracy was born of no theorist's dream; it was not carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier," said Turner. In the thesis, the American frontier

established liberty by releasing Americans from European mindsets and

eroding old, dysfunctional customs. The frontier had no need for

standing armies, established churches, aristocrats or nobles, nor for

landed gentry who controlled most of the land and charged heavy rents.

Frontier land was free for the taking. Turner first announced his

thesis in a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", delivered to the American Historical Association

in 1893 in Chicago. He won wide acclaim among historians and

intellectuals. Turner elaborated on the theme in his advanced history

lectures and in a series of essays published over the next 25 years,

published along with his initial paper as The Frontier in American History.

Turner's emphasis on the importance of the frontier in shaping American

character influenced the interpretation found in thousands of scholarly

histories. By the time Turner died in 1932, 60% of the leading history

departments in the U.S. were teaching courses in frontier history along

Turnerian lines.

Americanization of California (1932) by Dean Cornwell

20th century

Freelance writer James Truslow Adams popularized the phrase "American Dream" in his 1931 book Epic of America:

But there has been also the American dream, that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position... The American dream, that has lured tens of millions of all nations to our shores in the past century has not been a dream of merely material plenty, though that has doubtlessly counted heavily. It has been much more than that. It has been a dream of being able to grow to fullest development as man and woman, unhampered by the barriers which had slowly been erected in the older civilizations, unrepressed by social orders which had developed for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class.

Martin Luther King Jr., in his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" (1963) rooted the civil rights movement in the African-American quest for the American Dream:

We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands ... when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

21st century

American Dream has long been associated with consumerism. According to Sierra Club’s

Dave Tilford, "With less than 5 percent of world population, the U.S.

uses one-third of the world’s paper, a quarter of the world’s oil, 23

percent of the coal, 27 percent of the aluminum, and 19 percent of the

copper."

Literature

The concept of the American Dream has been used in popular discourse,

and scholars have traced its use in American literature ranging from

the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, to Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Willa Cather's My Ántonia, F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1925), Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy (1925) and Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon (1977). Other writers who used the American Dream theme include Hunter S. Thompson, Edward Albee, John Steinbeck, Langston Hughes, and Giannina Braschi. The American Dream is also discussed in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman as the play's protagonist, Willy, is on a quest for the American Dream.

As Huang shows, the American Dream is a recurring theme in the fiction of Asian Americans.

American ideals

Many American authors added American ideals to their work as a theme or other reoccurring idea, to get their point across. There are many ideals that appear in American literature such as, but not limited to, all people are equal, The United States of America

is the Land of Opportunity, independence is valued, The American Dream

is attainable, and everyone can succeed with hard work and

determination. John Winthrop also wrote about this term called, American exceptionalism. This ideology refers to the idea that Americans are, as a nation, elect.

Literary commentary

European

governments, worried that their best young people would leave for

America, distributed posters like this to frighten them (this 1869

Swedish anti-emigration poster contrasts Per Svensson's dream of the

American idyll (left) and the reality of his life in the wilderness

(right), where he is menaced by a mountain lion, a big snake and wild

Indians who are scalping and disembowelling someone).

The American Dream has been credited with helping to build a cohesive

American experience, but has also been blamed for inflated

expectations. Some commentators have noted that despite deep-seated belief in the egalitarian American Dream, the modern American wealth structure still perpetuates racial and class inequalities between generations. One sociologist

notes that advantage and disadvantage are not always connected to

individual successes or failures, but often to prior position in a

social group.

Since the 1920s, numerous authors, such as Sinclair Lewis in his 1922 novel Babbitt, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his 1925 classic, The Great Gatsby, satirized or ridiculed materialism

in the chase for the American dream. For example, Jay Gatsby's death

mirrors the American Dream's demise, reflecting the pessimism of

modern-day Americans. The American Dream is a main theme in the book by John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men. The two friends George and Lennie dream of their own piece of land with a ranch,

so they can "live off the fatta the lan'" and just enjoy a better life.

The book later shows that not everyone can achieve the American Dream,

thus proving by contradiction it is not possible for all, although it is

possible to achieve for a few. A lot of people follow the American

Dream to achieve a greater chance of becoming rich. Some posit that the

ease of achieving the American Dream changes with technological

advances, availability of infrastructure and information, government

regulations, state of the economy, and with the evolving cultural values

of American demographics.

In 1949, Arthur Miller wrote Death of a Salesman, in which the American Dream is a fruitless pursuit. Similarly, in 1971 Hunter S. Thompson depicted in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey Into the Heart of the American Dream a dark psychedelic reflection of the concept—successfully illustrated only in wasted pop-culture excess.

The novel Requiem for a Dream

by Hubert Selby Jr. is an exploration of the pursuit of American

success as it turns delirious and lethal, told through the ensuing

tailspin of its main characters. George Carlin famously wrote the joke "it's called the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe it".

Carlin pointed to "the big wealthy business interests that control

things and make all the important decisions" as having a greater

influence than an individual's choice. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges echos this sentiment in his 2012 book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt:

The vaunted American dream, the idea that life will get better, that progress is inevitable if we obey the rules and work hard, that material prosperity is assured, has been replaced by a hard and bitter truth. The American dream, we now know, is a lie. We will all be sacrificed. The virus of corporate abuse – the perverted belief that only corporate profit matters – has spread to outsource our jobs, cut the budgets of our schools, close our libraries, and plague our communities with foreclosures and unemployment.

The American Dream, and the sometimes dark response to it, has been a long-standing theme in American film. Many counterculture films of the 1960s and 1970s ridiculed the traditional quest for the American Dream. For example, Easy Rider (1969), directed by Dennis Hopper, shows the characters making a pilgrimage in search of "the true America" in terms of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyles.

Political leaders

Scholars have explored the American Dream theme in the careers of numerous political leaders, including Henry Kissinger, Hillary Clinton, Benjamin Franklin, and Abraham Lincoln. The theme has been used for many local leaders as well, such as José Antonio Navarro, the Tejano leader (1795–1871), who served in the legislatures of Coahuila y Texas, the Republic of Texas, and the State of Texas.

In 2006 U.S. Senator Barack Obama wrote a memoir, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream.

It was this interpretation of the American Dream for a young black man

that helped establish his statewide and national reputations. The exact meaning of the Dream became for at least one commentator a partisan political issue in the 2008 and 2012 elections.

Political conflicts, to some degree, have been ameliorated by the

shared values of all parties in the expectation that the American Dream

will resolve many difficulties and conflicts.

Public opinion

"A lot of Americans

think the U.S. has more social mobility than other western

industrialized countries. This (study using medians instead of averages

that underestimate the range and show less stark distinctions between

the top and bottom tiers) makes it abundantly clear that we have less.

Your circumstances at birth—specifically, what your parents do for a

living—are an even bigger factor in how far you get in life than we had

previously realized. Generations of Americans considered the United

States to be a land of opportunity. This research raises some sobering

questions about that image."— Michael Hout, Professor of Sociology at New York University

The ethos today implies an opportunity for Americans to achieve

prosperity through hard work. According to The Dream, this includes the

opportunity for one's children to grow up and receive a good education

and career without artificial barriers. It is the opportunity to make

individual choices without the prior restrictions that limited people

according to their class, caste, religion, race, or ethnicity.

Immigrants to the United States sponsored ethnic newspapers in their own

language; the editors typically promoted the American Dream. Lawrence Samuel argues:

For many in both the working class and the middle class, upward mobility has served as the heart and soul of the American Dream, the prospect of "betterment" and to "improve one's lot" for oneself and one's children much of what this country is all about. "Work hard, save a little, send the kids to college so they can do better than you did, and retire happily to a warmer climate" has been the script we have all been handed.

A key element of the American Dream is promoting opportunity for

one's children, Johnson interviewing parents says, "This was one of the

most salient features of the interview data: parents—regardless of

background—relied heavily on the American Dream to understand the

possibilities for children, especially their own children".

Rank et al. argue, "The hopes and optimism that Americans possess

pertain not only to their own lives, but to their children's lives as

well. A fundamental aspect of the American Dream has always been the

expectation that the next generation should do better than the previous

generation."

Hanson and Zogby (2010) report on numerous public opinion polls

that since the 1980s have explored the meaning of the concept for

Americans, and their expectations for its future. In these polls, a

majority of Americans consistently reported that for their family, the

American Dream is more about spiritual happiness than material goods.

Majorities state that working hard is the most important element for

getting ahead. However, an increasing minority stated that hard work and

determination does not guarantee success. Most Americans predict that

achieving the Dream with fair means will become increasingly difficult

for future generations. They are increasingly pessimistic about the

opportunity for the working class to get ahead; on the other hand, they

are increasingly optimistic about the opportunities available to poor

people and to new immigrants. Furthermore, most support programs make

special efforts to help minorities get ahead.

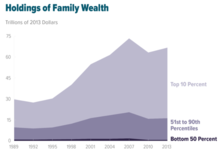

Wealth inequality in the United States increased from 1989 to 2013.

In a 2013 poll by YouGov, 41% of responders said it is impossible for most to achieve the American Dream, while 38% said it is still possible. Most Americans perceive a college education as the ticket to the American Dream. Some recent observers warn that soaring student loan debt crisis and shortages of good jobs may undermine this ticket. The point was illustrated in The Fallen American Dream, a documentary film that details the concept of the American Dream from its historical origins to its current perception.

Research published in 2013 shows that the US provides, alongside

the United Kingdom and Spain, the least economic mobility of any of 13

rich, democratic countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Prior research suggested that the United States shows roughly average

levels of occupational upward mobility and shows lower rates of income

mobility than comparable societies. Blanden et al. report, "the idea of the US as 'the land of opportunity' persists; and clearly seems misplaced."

According to these studies, "by international standards, the United

States has an unusually low level of intergenerational mobility: our

parents' income is highly predictive of our incomes as adults.

Intergenerational mobility in the United States is lower than in France, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Finland, Norway and Denmark.

Research in 2006 found that among high-income countries for which

comparable estimates are available, only the United Kingdom had a lower

rate of mobility than the United States." Economist Isabel Sawhill concluded that "this challenges the notion of America as the land of opportunity". Several public figures and commentators, from David Frum to Richard G. Wilkinson,

have noted that the American dream is better realized in Denmark, which

is ranked as having the highest social mobility in the OECD.[61] In 2015, economist Joseph Stiglitz stated, "Maybe we should be calling the American Dream the Scandinavian Dream."

In the United States, home ownership is sometimes used as a proxy for achieving the promised prosperity; home ownership has been a status symbol separating the middle classes from the poor.

Sometimes the Dream is identified with success in sports or how working class immigrants seek to join the American way of life.

According to a 2020 American Journal of Political Science study, Americans become less likely to believe in the attainability of the American dream as income equality increases.

Four dreams of consumerism

Ownby (1999) identifies four American Dreams that the new consumer

culture addressed. The first was the "Dream of Abundance" offering a

cornucopia of material goods to all Americans, making them proud to be

the richest society on earth. The second was the "Dream of a Democracy

of Goods" whereby everyone had access to the same products regardless of

race, gender, ethnicity, or class, thereby challenging the aristocratic

norms of the rest of the world whereby only the rich or well-connected

are granted access to luxury. The "Dream of Freedom of Choice" with its

ever-expanding variety of good allowed people to fashion their own

particular lifestyle. Finally, the "Dream of Novelty", in which

ever-changing fashions, new models, and unexpected new products

broadened the consumer experience in terms of purchasing skills and

awareness of the market, and challenged the conservatism of traditional

society and culture, and even politics. Ownby acknowledges that the

dreams of the new consumer culture radiated out from the major cities,

but notes that they quickly penetrated the most rural and most isolated

areas, such as rural Mississippi. With the arrival of the model T

after 1910, consumers in rural America were no longer locked into local

general stores with their limited merchandise and high prices in

comparison to shops in towns and cities. Ownby demonstrates that poor

black Mississippians shared in the new consumer culture, both inside

Mississippi, and it motivated the more ambitious to move to Memphis or

Chicago.

Other parts of the world

The aspirations of the "American Dream" in the broad sense of upward

mobility has been systematically spread to other nations since the 1890s

as American missionaries and businessmen consciously sought to spread

the Dream, says Rosenberg. Looking at American business, religious

missionaries, philanthropies, Hollywood, labor unions

and Washington agencies, she says they saw their mission not in

catering to foreign elites but instead reaching the world's masses in

democratic fashion. "They linked mass production,

mass marketing, and technological improvement to an enlightened

democratic spirit ... In the emerging litany of the American dream what

historian Daniel Boorstin later termed a "democracy of things" would

disprove both Malthus's predictions of scarcity and Marx's of class conflict." It was, she says "a vision of global social progress." Rosenberg calls the overseas version of the American Dream "liberal-developmentalism" and identified five critical components:

(1) belief that other nations could and should replicate America's own developmental experience; (2) faith in private free enterprise; (3) support for free or open access for trade and investment; (4) promotion of free flow of information and culture; and (5) growing acceptance of [U.S.] governmental activity to protect private enterprise and to stimulate and regulate American participation in international economic and cultural exchange.

Knights and McCabe argued American management gurus have taken the

lead in exporting the ideas: "By the latter half of the twentieth

century they were truly global and through them the American Dream

continues to be transmitted, repackaged and sold by an infantry of

consultants and academics backed up by an artillery of books and

videos".

After World War II

In West Germany after World War II, says Reiner Pommerin,

"the most intense motive was the longing for a better life, more or

less identical with the American dream, which also became a German

dream". Cassamagnaghi argues that to women in Italy after 1945, films and magazine stories about American life offered an "American dream." New York City especially represented a sort of utopia

where every sort of dream and desire could become true. Italian women

saw a model for their own emancipation from second class status in their

patriarchal society.

Britain

The American dream regarding home ownership had little resonance before the 1980s. In the 1980s, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher worked to create a similar dream, by selling public-housing

units to their tenants. Her Conservative Party called for more home

ownership: "HOMES OF OUR OWN: To most people ownership means first and

foremost a home of their own ... We should like in time to improve on

existing legislation with a realistic grants scheme to assist first-time

buyers of cheaper homes." Guest calls this Thatcher's approach to the American Dream.

Knights and McCabe argue that, "a reflection and reinforcement of the

American Dream has been the emphasis on individualism as extolled by

Margaret Thatcher and epitomized by the 'enterprise' culture."

Russia

Since the fall of Communism in the Soviet Union in 1991, the American Dream has fascinated Russians. The first post-Communist leader Boris Yeltsin embraced the "American way" and teamed up with Harvard University free market economists Jeffrey Sachs and Robert Allison to give Russia economic shock therapy in the 1990s. The newly independent Russian media idealized America and endorsed shock therapy for the economy. In 2008 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev

lamented the fact that 77% of Russia's 142 million people live "cooped

up" in apartment buildings. In 2010 his administration announced a plan

for widespread home ownership: "Call it the Russian dream", said

Alexander Braverman, the Director of the Federal Fund for the Promotion

of Housing Construction Development. Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, worried about his nation's very low birth rate, said he hoped home ownership will inspire Russians "to have more babies".

China

Shanghai in 2016

The Chinese Dream describes a set of ideals in the People's Republic of China.

It is used by journalists, government officials and activists to

describe the aspiration of individual self-improvement in Chinese

society. Although the phrase has been used previously by Western

journalists and scholars, a translation of a New York Times article written by the American journalist Thomas Friedman, "China Needs Its Own Dream", has been credited with popularizing the concept in China. He attributes the term to Peggy Liu and the environmental NGO JUCCCE's China Dream project, which defines the Chinese Dream as sustainable development. In 2013, China's new paramount leader Xi Jinping began promoting the phrase as a slogan, leading to its widespread use in the Chinese media.

The concept of Chinese Dream is very similar to the idea of "American Dream". It stresses entrepreneurship and glorifies a generation of self-made men and women in post-reform

China, such as rural immigrants who moved to the urban centers and

achieve magnificent improvement in terms of their living standards, and

social life. Chinese Dream can be interpreted as the collective

consciousness of Chinese people during the era of social transformation

and economic progress.

The idea was put forward by Chinese Communist Party new General Secretary Xi Jinping

on November 29, 2012. The government hoped to revitalize China, while

promoting innovation and technology to boost the international prestige

of China. In this light, the Chinese Dream, like American exceptionalism, is a nationalistic concept as well.

Some 90% of Chinese families own their own homes, giving the country one of the highest rates of home ownership in the world.

China is the world's fastest-growing consumer market. According to biologist Paul R. Ehrlich, "If everyone consumed resources at the US level, you will need another four or five Earths."