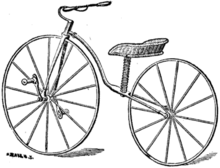

1886 Swift Safety Bicycle

Vehicles for human transport

that have two wheels and require balancing by the rider date back to

the early 19th century. The first means of transport making use of two

wheels arranged consecutively, and thus the archetype of the bicycle,

was the German draisine dating back to 1817. The term bicycle was coined in France in the 1860s, and the descriptive title "penny farthing", used to describe an "ordinary bicycle", is a 19th-century term.

Earliest unverified bicycle

There are several early, but unverified claims for the invention of the bicycle.

A sketch from around 1500 AD is attributed to Gian Giacomo Caprotti, a pupil of Leonardo da Vinci, but it was described by Hans-Erhard Lessing in 1998 as a purposeful fraud.

However, the authenticity of the bicycle sketch is still vigorously

maintained by followers of Prof. Augusto Marinoni, a lexicographer and

philologist, who was entrusted by the Commissione Vinciana of Rome with

the transcription of Leonardo's Codex Atlanticus.

Later, and equally unverified, is the contention that a certain "Comte de Sivrac" developed a célérifère in 1792, demonstrating it at the Palais-Royal in France. The célérifère

supposedly had two wheels set on a rigid wooden frame and no steering,

directional control being limited to that attainable by leaning.

A rider was said to have sat astride the machine and pushed it along

using alternate feet. It is now thought that the two-wheeled célérifère

never existed (though there were four-wheelers) and it was instead a

misinterpretation by the well-known French journalist Louis Baudry de

Saunier in 1891.

19th century

1817 to 1819: the draisine or velocipede

Wooden draisine (around 1820), the earliest two-wheeler

Drais's 1817 design made to measure

The first verifiable claim for a practically used bicycle belongs to German Baron Karl von Drais, a civil servant to the Grand Duke of Baden in Germany. Drais invented his Laufmaschine (German for "running machine") in 1817, that was called Draisine (English) or draisienne

(French) by the press. Karl von Drais patented this design in 1818,

which was the first commercially successful two-wheeled, steerable,

human-propelled machine, commonly called a velocipede, and nicknamed hobby-horse or dandy horse. It was initially manufactured in Germany and France.

Hans-Erhard Lessing (Drais's biographer) found from

circumstantial evidence that Drais's interest in finding an alternative

to the horse was the starvation and death of horses caused by crop

failure in 1816, the Year Without a Summer (following the volcanic eruption of Tambora in 1815).

On his first reported ride from Mannheim on June 12, 1817, he covered 13 km (eight miles) in less than an hour.

Constructed almost entirely of wood, the draisine weighed 22 kg (48

pounds), had brass bushings within the wheel bearings, iron shod wheels,

a rear-wheel brake and 152 mm (6 inches) of trail of the front-wheel

for a self-centering caster

effect. This design was welcomed by mechanically minded men daring to

balance, and several thousand copies were built and used, primarily in

Western Europe and in North America. Its popularity rapidly faded when,

partly due to increasing numbers of accidents, some city authorities

began to prohibit its use. However, in 1866 Paris a Chinese visitor

named Bin Chun could still observe foot-pushed velocipedes.

Denis Johnson's son riding a velocipede, Lithograph 1819.

The concept was picked up by a number of British cartwrights; the most notable was Denis Johnson of London announcing in late 1818 that he would sell an improved model.

New names were introduced when Johnson patented his machine “pedestrian

curricle” or “velocipede,” but the public preferred nicknames like

“hobby-horse,” after the children's toy or, worse still, “dandyhorse,”

after the foppish men who often rode them. Johnson's machine was an improvement on Drais's, being notably more elegant: his wooden frame had a serpentine shape

instead of Drais's straight one, allowing the use of larger wheels

without raising the rider's seat, but was still the same design.

During the summer of 1819, the "hobby-horse", thanks in part to

Johnson's marketing skills and better patent protection, became the

craze and fashion in London society. The dandies, the Corinthians of the

Regency, adopted it, and therefore the poet John Keats

referred to it as "the nothing" of the day. Riders wore out their boots

surprisingly rapidly, and the fashion ended within the year, after

riders on pavements (sidewalks) were fined two pounds.

Nevertheless, Drais's velocipede provided the basis for further

developments: in fact, it was a draisine which inspired a French

metalworker around 1863 to add rotary cranks and pedals to the front-wheel hub, to create the first pedal-operated "bicycle" as we today understand the word.

1820s to 1850s: an era of 3 and 4-wheelers

A couple seated on an 1886 Coventry Rotary Quadracycle for two.

McCall's first (top) and improved velocipede of 1869 – later predated to 1839 and attributed to MacMillan

Though technically not part of two-wheel ("bicycle") history, the

intervening decades of the 1820s–1850s witnessed many developments

concerning human-powered vehicles

often using technologies similar to the draisine, even if the idea of a

workable two-wheel design, requiring the rider to balance, had been

dismissed. These new machines had three wheels (tricycles) or four (quadracycles)

and came in a very wide variety of designs, using pedals, treadles, and

hand-cranks, but these designs often suffered from high weight and high

rolling resistance. However, Willard Sawyer in Dover successfully manufactured a range of treadle-operated 4-wheel vehicles and exported them worldwide in the 1850s.

1830s: the reported Scottish inventions

The first mechanically propelled two-wheel vehicle is believed by some to have been built by Kirkpatrick Macmillan, a Scottish blacksmith, in 1839. A nephew later claimed that his uncle developed a rear-wheel drive design using mid-mounted treadles connected by rods to a rear crank, similar to the transmission of a steam locomotive. Proponents associate him with the first recorded instance of a bicycling traffic offence, when a Glasgow

newspaper reported in 1842 an accident in which an anonymous "gentleman

from Dumfries-shire... bestride a velocipede... of ingenious design"

knocked over a pedestrian in the Gorbals and was fined five shillings.

However, the evidence connecting this with Macmillan is weak, since it

is unlikely that the artisan Macmillan would have been termed a gentleman, nor is the report clear on how many wheels the vehicle had. The evidence is unclear, and may have been faked by his son.

A similar machine was said to have been produced by Gavin Dalzell

of Lesmahagow, circa 1845. There is no record of Dalzell ever having

laid claim to inventing the machine. It is believed that he copied the

idea having recognised the potential to help him with his local drapery

business and there is some evidence that he used the contraption to take

his wares into the rural community around his home. A replica still

exists today in the Glasgow Museum of Transport. The exhibit holds the

honour of being the oldest bike in existence today. The first documented producer of rod-driven two-wheelers, treadle bicycles, was Thomas McCall, of Kilmarnock in 1869. The design was inspired by the French front-crank velocipede of the Lallement/Michaux type.

1853 and the invention of the first bicycle with pedals "Tretkurbelfahrrad" by Philipp Moritz Fischer

Once

again Germany was the center of innovation, when Philipp Moritz

Fischer, who had used the Draisine since he was 9 years old for going to

school, invented the very first bicycle with pedals. in 1853. After

years of living all over Europe, he left London to go back to his native

town of Schweinfurt

, Bavaria, when his first son died at a young age. He built the very

first bicycle with pedals in 1853. The Tretkurbelfahrrad from 1853 is

still sustained and is on public display in the municipality museum in

Schweinfurt.

1860s and the Michaux "Velocipede," aka "Boneshaker"

The

first widespread and commercially successful design was French. An

example is at the Museum of Science and Technology, Ottawa.

Initially developed around 1863, it sparked a fashionable craze briefly

during 1868–70. Its design was simpler than the Macmillan bicycle; it

used rotary cranks and pedals mounted to the front wheel hub. Pedaling

made it easier for riders to propel the machine at speed, but the

rotational speed limitation of this design created stability and comfort

concerns which would lead to the large front wheel of the "penny

farthing". It was difficult to pedal the wheel that was used for

steering. The use of metal frames reduced the weight and provided

sleeker, more elegant designs, and also allowed mass-production. Different braking mechanisms were used depending on the manufacturer. In England, the velocipede earned the name of "bone-shaker" because of its rigid frame and iron-banded wheels that resulted in a "bone-shaking experience for riders."

The velocipede's renaissance began in Paris

during the late 1860s. Its early history is complex and has been

shrouded in some mystery, not least because of conflicting patent

claims: all that has been stated for sure is that a French metalworker

attached pedals to the front wheel; at present, the earliest year

bicycle historians agree on is 1864. The identity of the person who

attached cranks is still an open question at International Cycling History Conferences (ICHC). The claims of Ernest Michaux and of Pierre Lallement, and the lesser claims of rear-pedaling Alexandre Lefebvre, have their supporters within the ICHC community.

The original pedal-bicycle, with the serpentine frame, from Pierre Lallement's US Patent No. 59,915 drawing, 1866

New York company Pickering and Davis invented this pedal-bicycle for ladies in 1869.

Bicycle historian David V. Herlihy documents that Lallement claimed

to have created the pedal bicycle in Paris in 1863. He had seen someone

riding a draisine in 1862 then originally came up with the idea to add

pedals to it. It is a fact that he filed the earliest and only patent

for a pedal-driven bicycle, in the US in 1866. Lallement's patent drawing

shows a machine which looks exactly like Johnson's draisine, but with

the pedals and rotary cranks attached to the front wheel hub, and a thin

piece of iron over the top of the frame to act as a spring supporting

the seat, for a slightly more comfortable ride.

By the early 1860s, the blacksmith Pierre Michaux, besides producing parts for the carriage trade, was producing "vélocipède à pédales" on a small scale. The wealthy Olivier brothers Aimé and René were students in Paris at this time, and these shrewd young entrepreneurs

adopted the new machine. In 1865 they travelled from Paris to Avignon

on a velocipede in only eight days. They recognized the potential

profitability of producing and selling the new machine. Together with

their friend Georges de la Bouglise, they formed a partnership with Pierre Michaux,

Michaux et Cie ("Michaux and company"), in 1868, avoiding use of the

Olivier family name and staying behind the scenes, lest the venture

prove to be a failure. This was the first company which mass-produced bicycles, replacing the early wooden frame with one made of two pieces of cast iron

bolted together—otherwise, the early Michaux machines look exactly like

Lallement's patent drawing. Together with a mechanic named Gabert in

his hometown of Lyon, Aimé Olivier created a diagonal single-piece frame

made of wrought iron which was much stronger, and as the first bicycle craze

took hold, many other blacksmiths began forming companies to make

bicycles using the new design. Velocipedes were expensive, and when

customers soon began to complain about the Michaux serpentine

cast-iron frames breaking, the Oliviers realized by 1868 that they

needed to replace that design with the diagonal one which their

competitors were already using, and the Michaux company continued to

dominate the industry in its first years.

On the new macadam paved boulevards of Paris it was easy riding, although initially still using what was essentially horse coach

technology. It was still called "velocipede" in France, but in the

United States, the machine was commonly called the "bone-shaker". Later

improvements included solid rubber tires and ball bearings.

Lallement had left Paris in July 1865, crossed the Atlantic, settled in

Connecticut and patented the velocipede, and the number of associated

inventions and patents soared in the US. The popularity of the machine

grew on both sides of the Atlantic and by 1868–69 the velocipede craze was strong in rural areas as well. Even in a relatively small city such as Halifax,

Nova Scotia, Canada, there were five velocipede rinks, and riding

schools began opening in many major urban centers. Essentially, the

velocipede was a stepping stone that created a market for bicycles that

led to the development of more advanced and efficient machines.

However, the Franco-Prussian war

of 1870 destroyed the velocipede market in France, and the

"bone-shaker" enjoyed only a brief period of popularity in the United

States, which ended by 1870. There is debate among bicycle historians

about why it failed in the United States, but one explanation is that

American road surfaces were much worse than European ones, and riding

the machine on these roads was simply too difficult. Certainly another

factor was that Calvin Witty had purchased Lallement's patent, and his

royalty demands soon crippled the industry. The UK was the only place

where the bicycle never fell completely out of favour.

1870s: the high-wheel bicycle

The high-bicycle was the logical extension of the boneshaker, the

front wheel enlarging to enable higher speeds (limited by the inside leg

measurement of the rider), the rear wheel shrinking and the frame being made lighter. Frenchman Eugène Meyer is now regarded as the father of the high bicycle by the ICHC in place of James Starley. Meyer invented the wire-spoke tension wheel in 1869 and produced a classic high bicycle design until the 1880s.

James Starley in Coventry

added the tangent spokes and the mounting step to his famous bicycle

named "Ariel." He is regarded as the father of the British cycling

industry. Ball bearings,

solid rubber tires and hollow-section steel frames became standard,

reducing weight and making the ride much smoother. Depending on the

rider's leg length, the front wheel could now have a diameter up to 60

in (1.5 m).

Starley's "Royal Salvo" tricycle, as owned by Queen Victoria

Much later, when this type of bicycle was beginning to be replaced

by a later design, it came to be referred to as the "ordinary bicycle".

(While it was in common use no such distinguishing adjective was used,

since there was then no other kind.) and was later nicknamed "penny-farthing" in England (a penny representing the front wheel, and a coin smaller in size and value, the farthing,

representing the rear). They were fast, but unsafe. The rider was high

up in the air and traveling at a great speed. If he hit a bad spot in

the road he could easily be thrown over the front wheel and be seriously

injured (two broken wrists were common, in attempts to break a fall) or even killed. "Taking a header" (also known as "coming a cropper"), was not at all uncommon.

The rider's legs were often caught underneath the handlebars, so

falling free of the machine was often not possible. The dangerous nature

of these bicycles (as well as Victorian

mores) made cycling the preserve of adventurous young men. The risk

averse, such as elderly gentlemen, preferred the more stable tricycles or quadracycles. In addition, women's fashion of the day made the "ordinary" bicycle inaccessible. Queen Victoria owned Starley's "Royal Salvo" tricycle, though there is no evidence she actually rode it.

Although French and English inventors modified the velocipede

into the high-wheel bicycle, the French were still recovering from the

Franco-Prussian war, so English entrepreneurs put the high-wheeler on

the English market, and the machine became very popular there, Coventry, Oxford, Birmingham and Manchester being the centers of the English bicycle industry (and of the arms or sewing machine industries, which had the necessary metalworking and engineering skills for bicycle manufacturing, as in Paris and St. Etienne, and in New England). Soon bicycles found their way across the English Channel. By 1875, high-wheel bicycles were becoming popular in France, though ridership expanded slowly.

In the United States, Bostonians such as Frank Weston started importing bicycles in 1877 and 1878, and Albert Augustus Pope started production of his "Columbia"

high-wheelers in 1878, and gained control of nearly all applicable

patents, starting with Lallement's 1866 patent. Pope lowered the royalty

(licensing fee) previous patent owners charged, and took his

competitors to court over the patents. The courts supported him, and

competitors either paid royalties ($10 per bicycle), or he forced them

out of business. There seems to have been no patent issue in France,

where English bicycles still dominated the market. In 1880, G.W. Pressey

invented the high-wheeler American Star Bicycle,

whose smaller front wheel was designed to decrease the frequency of

"headers". By 1884 high-wheelers and tricycles were relatively popular

among a small group of upper-middle-class people in all three countries,

the largest group being in England. Their use also spread to the rest

of the world, chiefly because of the extent of the British Empire.

Pope also introduced mechanization and mass production (later copied and adopted by Ford and General Motors), vertically integrated, (also later copied and adopted by Ford), advertised aggressively (as much as ten percent of all advertising in U.S. periodicals in 1898 was by bicycle makers), promoted the Good Roads Movement (which had the side benefit of acting as advertising, and of improving sales by providing more places to ride), and litigated on behalf of cyclists (It would, however, be Western Wheel Company of Chicago which would drastically reduce production costs by introducing stamping to the production process in place of machining, significantly reducing costs, and thus prices.) In addition, bicycle makers adopted the annual model change (later derided as planned obsolescence, and usually credited to General Motors), which proved very successful.

Even so, bicycling remained the province of the urban well-to-do, and mainly men, until the 1890s, and was an example of conspicuous consumption.

The safety bicycle: 1880s and 1890s

An 1884 McCammon safety bicycle

An 1885 Whippet safety bicycle

An 1889 Lady's safety bicycle

The development of the safety bicycle

was arguably the most important change in the history of the bicycle.

It shifted their use and public perception from being a dangerous toy

for sporting young men to being an everyday transport tool for men and

women of all ages.

Aside from the obvious safety problems, the high-wheeler's direct

front wheel drive limited its top speed. One attempt to solve both

problems with a chain-driven front wheel was the dwarf bicycle,

exemplified by the Kangaroo. Inventors also tried a rear wheel chain drive. Although Harry John Lawson

invented a rear-chain-drive bicycle in 1879 with his "bicyclette", it

still had a huge front wheel and a small rear wheel. Detractors called

it "The Crocodile", and it failed in the market.

John Kemp Starley,

James's nephew, produced the first successful "safety bicycle" (again a

retrospective name), the "Rover," in 1885, which he never patented. It

featured a steerable front wheel that had significant caster, equally sized wheels and a chain drive to the rear wheel.

Widely imitated, the safety bicycle completely replaced the

high-wheeler in North America and Western Europe by 1890. Meanwhile, John Dunlop's reinvention of the pneumatic bicycle tire

in 1888 had made for a much smoother ride on paved streets; the

previous type were quite smooth-riding, when used on the dirt roads

common at the time.

As with the original velocipede, safety bicycles had been much less

comfortable than high-wheelers precisely because of the smaller wheel

size, and frames were often buttressed with complicated bicycle suspension

spring assemblies. The pneumatic tire made all of these obsolete, and

frame designers found a diamond pattern to be the strongest and most

efficient design.

On 10 October 1889, Isaac R Johnson, an African-American

inventor, lodged his patent for a folding bicycle – the first with a

recognisably modern diamond frame, the pattern still used in

21st-century bicycles.

The chain drive improved comfort and speed, as the drive was

transferred to the non-steering rear wheel and allowed for smooth,

relaxed and injury free pedaling (earlier designs that required

pedalling the steering front wheel were difficult to pedal while

turning, due to the misalignment of rotational planes of leg and pedal).

With easier pedaling, the rider more easily turned corners.

The pneumatic tire and the diamond frame improved rider comfort

but do not form a crucial design or safety feature. A hard rubber tire

on a bicycle is just as rideable but is bone jarring. The frame design

allows for a lighter weight, and more simple construction and

maintenance, hence lower price.

Most likely the first electric bicycle was built in 1897 by Hosea W. Libbey.

a ca. 1887 color print

20th century

The roadster

Bicycle in Plymouth at the start of the 20th century

The ladies' version of the roadster's design was very much in place

by the 1890s. It had a step-through frame rather than the diamond frame

of the gentlemen's model so that ladies, with their dresses and skirts,

could easily mount and ride their bicycles, and commonly came with a

skirt guard to prevent skirts and dresses becoming entangled in the rear

wheel and spokes. As with the gents' roadster, the frame was of steel

construction and the positioning of the frame and handlebars gave the

rider a very upright riding position. Though they originally came with

front spoon-brakes, technological advancements meant that later models

were equipped with the much-improved coaster brakes or rod-actuated rim

or drum-brakes.

The Dutch cycle industry grew rapidly from the 1890s onwards. Since by then it was the British who had the strongest and best-developed market in bike design, Dutch framemakers either copied them or imported them from England. In 1895, 85 percent of all bikes bought in the Netherlands were from Britain; the vestiges of that influence can still be seen in the solid, gentlemanly shape of a traditional Dutch bike even now.

1897

Though the ladies' version of the roadster largely fell out of

fashion in England and many other Western nations as the 20th century

progressed, it remains popular in the Netherlands; this is why some

people refer to bicycles of this design as Dutch bikes. In Dutch the

name of these bicycles is Omafiets ("grandma's bike").

Popularity in Europe, decline in US

Cycling

steadily became more important in Europe over the first half of the

twentieth century, but it dropped off dramatically in the United States

between 1900 and 1910. Automobiles became the preferred means of

transportation. Over the 1920s, bicycles gradually became considered

children's toys, and by 1940 most bicycles in the United States were

made for children. In Europe cycling remained an adult activity, and

bicycle racing, commuting, and "cyclotouring" were all popular activities. In addition, specialist bicycles for children appeared before 1916.

From the early 20th century until after World War II, the

roadster constituted most adult bicycles sold in the United Kingdom and

in many parts of the British Empire. For many years after the advent of

the motorcycle and automobile, they remained a primary means of adult

transport. Major manufacturers in England were Raleigh and BSA, though

Carlton, Phillips, Triumph, Rudge-Whitworth, Hercules, and Elswick

Hopper also made them.

Technical innovations

Bicycles continued to evolve to suit the varied needs of riders. The derailleur

developed in France between 1900 and 1910 among cyclotourists, and was

improved over time. Only in the 1930s did European racing organizations

allow racers to use gearing;

until then they were forced to use a two-speed bicycle. The rear wheel

had a sprocket on either side of the hub. To change gears, the rider had

to stop, remove the wheel, flip it around, and remount the wheel. When

racers were allowed to use derailleurs, racing times immediately

dropped.

World War II

German Wehrmacht Radfahrtruppe bicycle troops

Although multiple-speed bicycles were widely known by this time, most or all military bicycles used in the Second World War were single-speed. Bicycles were used by paratroopers

during the war to help them with transportation, creating the term

"bomber bikes" to refer to US planes dropping bikes for troops to use. The German Volksgrenadier units each had a battalion of bicycle infantry attached. The Invasion of Poland

saw many bicycle-riding scouts in use, with each bicycle company using

196 bicycles and 1 motorcycle. By September 1939, there were 41 bicycle

companies mobilized.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan used around 50,000 bicycle troops. The Malayan Campaign

saw many bicycles used. The Japanese confiscated bicycles from

civilians due to the abundance of bicycles among the civilian

population.

Japanese bicycle troops were efficient in both speed and carrying

capacity, as they could carry 36 kilograms of equipment compared to a

normal British soldier, which could carry 18 kilograms.

China and the Flying Pigeon

The Flying Pigeon

was at the forefront of the bicycle phenomenon in the People's Republic

of China. The vehicle was the government approved form of transport,

and the nation became known as zixingche wang guo (自行车王国) — the

'Kingdom of Bicycles'. A bicycle was regarded as one of the three

"must-haves" of every citizen, alongside a sewing machine and watch –

essential items in life that also offered a hint of wealth. The Flying

Pigeon bicycle became a symbol of an egalitarian social system that

promised little comfort but a reliable ride through life.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the logo became synonymous with

almost all bicycles in the country. The Flying Pigeon became the single

most popular mechanized vehicle on the planet, becoming so ubiquitous

that Deng Xiaoping — the post-Mao leader who launched China's economic

reforms in the 1970s — defined prosperity as "a Flying Pigeon in every

household".

In the early 1980s, Flying Pigeon was the country's biggest bike

manufacturer, selling 3 million cycles in 1986. Its 20-kilo black

single-speed models were popular with workers, and there was a waiting

list of several years to get one, and even then buyers needed good guanxi (relationship) in addition to the purchase cost, which was about four months' wages for most workers.

North America: Cruiser VS Racer

At mid-century there were two predominant bicycle styles for recreational cyclists in North America. Heavyweight cruiser bicycles, preferred by the typical (hobby) cyclist,

featuring balloon tires, pedal-driven "coaster" brakes and only one

gear, were popular for their durability, comfort, streamlined

appearance, and a significant array of accessories (lights, bells,

springer forks, speedometers, etc..). Lighter cycles, with hand brakes, narrower tires, and a three-speed hub gearing

system, often imported from England, first became popular in the United

States in the late 1950s. These comfortable, practical bicycles usually

offered generator-powered headlamps, safety reflectors, kickstands, and

frame-mounted tire pumps. In the United Kingdom, like the rest of

Europe, cycling was seen as less of a hobby, and lightweight but durable

bikes had been preferred for decades.

In the United States, the sports roadster was imported after

World War II, and was known as the "English racer". It quickly became

popular with adult cyclists seeking an alternative to the traditional

youth-oriented cruiser bicycle. While the English racer was no racing

bike, it was faster and better for climbing hills than the cruiser,

thanks to its lighter weight, tall wheels, narrow tires, and internally

geared rear hubs. In the late 1950s, U.S. manufacturers such as Schwinn

began producing their own "lightweight" version of the English racer.

This racing bicycle has aluminum tubing, carbon fiber stays and forks, a drop handlebar, and narrow tires and wheels.

In the late 1960s, Americans' increasing consciousness of the value of exercise and later the advantage of energy efficient transportation led to the American bike boom of the 1970s.

Annual U.S. sales of adult bicycles doubled between 1960 and 1970, and

doubled again between 1971 and 1975, the peak years of the adult

cycling boom in the United States, eventually reaching nearly 17 million

units.

Most of these sales were to new cyclists, who overwhelmingly preferred models imitating popular European derailleur-equipped racing bikes — variously called sports models, sport/tourers, or simply ten-speeds — to the older roadsters with hub gears which remained much the same as they had been since the 1930s. These lighter bicycles, long used by serious cyclists and by racers, featured dropped handlebars, narrow tires, derailleur gears,

five to fifteen speeds, and a narrow 'racing' type saddle. By 1980,

racing and sport/touring derailleur bikes dominated the market in North

America. Fatbike was invented for off-road usage in 1980.

Europe

In

Britain, the utility roadster declined noticeably in popularity during

the early 1970s, as a boom in recreational cycling caused manufacturers

to concentrate on lightweight (10–14 kg (23–30 lb)), affordable

derailleur sport bikes, actually slightly-modified versions of the racing bicycle of the era.

In the early 1980s, Swedish company Itera invented a new type of bicycle, made entirely of plastic. It was a commercial failure.

In the 1980s, U.K. cyclists began to shift from road-only

bicycles to all-terrain models such as the mountain bike. The mountain

bike's sturdy frame and load-carrying ability gave it additional

versatility as a utility bike, usurping the role previously filled by

the roadster. By 1990, the roadster was almost dead; while annual U.K.

bicycle sales reached an all-time record of 2.8 million, almost all of

them were mountain and road/sport models.

BMX bikes

BMX bikes

are specially designed bicycles that usually have 16 to 24-inch wheels

(the norm being the 20-inch wheel), which originated in the state of California in the early 1970s when teenagers imitated their motocross heroes on their bicycles. Children were racing standard road bikes off-road, around purpose-built tracks in the Netherlands. The 1971 motorcycle racing documentary On Any Sunday is generally credited with inspiring the movement nationally in the US. In the opening scene, kids are shown riding their Schwinn Sting-Rays

off-road. It was not until the middle of the decade the sport achieved

critical mass, and manufacturers began creating bicycles designed

specially for the sport.

It has grown into an international sport with several different disciplines such as Freestyle, Racing, Street, and Flatland.

Mountain bikes

In 1981, the first mass-produced mountain bike

appeared, intended for use off-pavement over a variety of surfaces. It

was an immediate success, and examples flew off retailers' shelves

during the 1980s, their popularity spurred by the novelty of all-terrain

cycling and the increasing desire of urban dwellers to escape their

surroundings via mountain biking and other extreme sports.

These cycles featured sturdier frames, wider tires with large knobs for

increased traction, a more upright seating position (to allow better

visibility and shifting of body weight), and increasingly, various front

and rear suspension designs. By 2000, mountain bike sales had far outstripped that of racing, sport/racer, and touring bicycles.

21st century

The

21st century has seen a continued application of technology to bicycles

(which started in the 20th century): in designing them, building them,

and using them. Bicycle frames and components continue to get lighter

and more aerodynamic without sacrificing strength largely through the

use of computer aided design, finite element analysis, and computational fluid dynamics. Recent discoveries about bicycle stability have been facilitated by computer simulations. Once designed, new technology is applied to manufacturing such as hydroforming and automated carbon fiber layup. Finally, electronic gadgetry has expanded from just cyclocomputers to now include cycling power meters and electronic gear-shifting systems.

The 2005 Giant Innova is an example of a typical 700C hybrid bicycle. It has 27 speeds, front fork and seat suspension, an adjustable stem and disc brakes for wet-weather riding.

Hybrid and commuter bicycles

In

recent years, bicycle designs have trended towards increased

specialization, as the number of casual, recreational and commuter

cyclists has grown. For these groups, the industry responded with the hybrid bicycle, sometimes marketed as a city bike, cross bike, or commuter bike.

Hybrid bicycles combine elements of road racing and mountain bikes,

though the term is applied to a wide variety of bicycle types.

Hybrid bicycles and commuter bicycles can range from fast and

light racing-type bicycles with flat bars and other minimal concessions

to casual use, to wider-tired bikes designed for primarily for comfort,

load-carrying, and increased versatility over a range of different road

surfaces. Enclosed hub gears

have become popular again – now with up to 8, 11 or 14 gears – for such

bicycles due to ease of maintenance and improved technology.

Recumbent bicycle

2008 Nazca Fuego short wheelbase recumbent with 20" front wheel and 26" rear wheel.

The recumbent bicycle was invented in 1893. In 1934, the Union Cycliste Internationale banned recumbent bicycles

from all forms of officially sanctioned racing, at the behest of the

conventional bicycle industry, after relatively little-known Francis Faure beat world champion Henri Lemoine and broke Oscar Egg's hour record by half a mile while riding Mochet's Velocar.

Some authors assert that this resulted in the stagnation of the upright

racing bike's frame geometry which has remained essentially unchanged

for 70 years. This stagnation finally started to reverse with the formation of the International Human Powered Vehicle Association which holds races for "banned" classes of bicycle. Sam Whittingham set a human powered speed record of 132 km/h (82 mph) on level ground in a faired recumbent streamliner in 2009 at Battle Mountain.

While historically most bike frames have been steel, recent

designs, particularly of high-end racing bikes, have made extensive use

of carbon and aluminum frames.

Recent years have also seen a resurgence of interest in balloon tire cruiser bicycles for their low-tech comfort, reliability, and style.

In addition to influences derived from the evolution of American

bicycling trends, European, Asian and African cyclists have also

continued to use traditional roadster bicycles, as their rugged design, enclosed chainguards, and dependable hub gearing make them ideal for commuting and utility cycling duty.