rom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Constitutional_Convention_of_the_United_States

The calling of a Second Constitutional Convention of the United States is a proposal made by some scholars and activists from across the political spectrum for the purpose of making substantive reforms to the United States Federal government by rewriting its Constitution.

The calling of a Second Constitutional Convention of the United States is a proposal made by some scholars and activists from across the political spectrum for the purpose of making substantive reforms to the United States Federal government by rewriting its Constitution.

Background

Since

the initial 1787–88 debate over ratification of the Constitution, there

have been sporadic calls for the convening of a second convention to

modify and correct perceived shortcomings in the Federal system it

established. Article V

of the Constitution provides two methods for amending the nation's

frame of government. The first method authorizes Congress, "whenever

two-thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary" (a two-thirds

majority of those members present—assuming that a quorum

exists at the time that the vote is cast—and not necessarily a

two-thirds majority vote of the entire membership elected and serving in

the two houses of Congress), to propose Constitutional amendments. The

second method requires Congress, "on the application of the legislatures

of two-thirds of the several states" (presently 34), to "call a

convention for proposing amendments".

In 1943, Alexander Hehmeyer, a lawyer for Chicago-based Marshall Field's department store as well as Time Inc., wrote A Time for Change (Farrar & Rinehart), in which he proposed a second Constitutional Convention to streamline the Federal Government. In the late 1960s, Senator Everett Dirksen called for a constitutional convention by appealing to state legislatures to summon one.

Three times in the 20th century, concerted efforts were

undertaken by proponents of particular issues to secure the number of

applications necessary to summon an Article V Convention. These included

conventions to consider amendments to (1) provide for popular election

of U.S. Senators; (2) permit the states to include factors other than

equality of population in drawing state legislative district boundaries; and (3) to propose an amendment

requiring the U.S. budget to be balanced under most circumstances. The

campaign for a popularly elected Senate is frequently credited with

"prodding" the Senate to join the House of Representatives in proposing

what became the Seventeenth Amendment to the states in 1912, while the latter two campaigns came very close to meeting the two-thirds threshold in the 1960s and 1980s, respectively.

In 2013, the number of states calling for a convention to consider a

balanced budget amendment was believed to be either 33 or 20, and the tally may depend on rulings about whether past state applications have been rescinded. In 1983, Missouri applied; in 2013, Ohio applied.

In January 1975, Congressman Jerry Pettis, Republican from California, introduced a concurrent resolution (94th H.Con.Res.28)

calling a convention to propose amendments to the Constitution. In it,

Pettis proposed that each state would be entitled to send as many

delegates to the convention as it had Senators and Representatives in

Congress and that such delegates would be selected in the manner

designated by the legislature of each state. Being a concurrent rather

than a joint resolution,

the legislation would not have—had it been adopted by both the House

and Senate—triggered a national Article V convention. Rather, it would

have conveyed the sentiments of Congress that one be called. On August

5, 1977, Representative Norman F. Lent, Republican from New York, introduced a similar concurrent resolution (95th H.Con.Res.340). Both were referred to the House Judiciary Committee. No further action on either was taken.

A report in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 2011 described the movement for a convention as gaining "traction" in public debate,

and wrote that "concern over a seemingly dysfunctional climate in

Washington and issues ranging from the national debt to the overwhelming

influence of money in politics have spawned calls for fundamental

change in the document that guides the nation's government." For several years, state lawmakers approved no Article V Convention calls at all, and even went so far as to adopt resolutions rescinding

their prior such calls. However, in 2011, legislators in Alabama,

Louisiana, and North Dakota (in two instances) approved resolutions

applying for an Article V Convention. All three of these states had

adopted rescissions in 1988, 1990, and 2001, respectively, but then

reversed course in 2011. The same was true in 2012 with New Hampshire

lawmakers who had adopted a resolution to rescind previous convention

applications as recently as 2010.

Columnist William Safire

A report by analyst David Gergen on CNN suggested that despite serious differences between left-leaning Occupy movements and the right-leaning Tea Party movements, there was considerable agreement on both sides that money plays "far too large a role in politics." Scholars such as Richard Labunski, Sanford Levinson, Lawrence Lessig, Glenn Reynolds, Larry Sabato, newspaper columnist William Safire, and activists such as John Booth of the Dallas movement RestoringFreedom.org have called for constitutional changes that would curb the dominant role of money in politics. Scholar Stein Ringen in his book Nation of Devils

suggested that only a "total overhaul" of the constitution could fix

the "years of accumulated damage and dysfunction," according to a report

in the Economist in 2013. French journalist Jean-Philippe Immarigeon suggested in Harper's Magazine that the "nearly 230-year-old constitution stretched past the limits of its usefulness". A report in USA Today suggested that 17 of 34 states have petitioned Congress for a convention to deal with the issue of a balanced budget amendment. A report on CNN

suggested that 30 state legislatures are considering resolutions either

calling for a constitutional convention or else proposing changes to

the Constitution. David O. Stewart suggested that possible topics for Constitutional amendments might include the elimination of the electoral college and switching to direct election of the president, a ban on procedures in the United States Senate which utilize a supermajority vote requirement as a means to prevent minorities or powerful Senators from blocking legislation, term limits for Senators and Representatives, and a balanced budget amendment.

Questions

Numerous questions surround the issue of how such an unprecedented convention might be conducted. There is no consensus on how such a convention may be organized, led, or who may be selected to be in such a body.

Because there has not been a constitutional convention since 1787, efforts have been clouded by unresolved legal questions: Do the calls for a convention have to happen at the same time? Can a convention be limited to just one topic? What if Congress simply refuses to call a convention? Scholars are split on all those issues.

— report in the Indianapolis Star, 2011

Precedent

While there is no precedent for such a convention, scholars have noted that the original 1787 Convention, itself, was the first precedent, as it had only been authorized to amend the Articles of Confederation, not to draw up an entirely new frame of government. According to The New York Times, the action by the Founding Fathers set up a precedent that could be used today. But, since 1787, there has not been an overall constitutional convention.

Instead, each time the amendment process has been initiated since 1789,

it has been initiated by Congress. All 33 amendments submitted to the

states for ratification originated there. The convention option, which Alexander Hamilton (writing in The Federalist No. 85) believed would serve as a barrier "against the encroachments of the national authority", has yet to be successfully invoked, although not for lack of activity in the states.

Scope of a possible convention

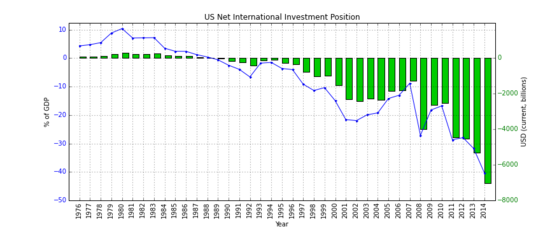

There have been calls for a second convention based on a single issue such as the Balanced Budget Amendment. According to one count, 17 of 34 states have petitioned Congress for a "convention to propose a balanced budget amendment."

But Congress has been reluctant to "impose limitations on its spending

and borrowing and taxing powers", according to anti-tax activist David

Biddulph.

Law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen suggested that such a convention

would have the "power to propose anything it sees fit" and that calls

for a convention to focus on only one issue "may not be valid",

according to this view.

According to Paulsen's count, 33 states have called for a general

convention, although some of these calls have been pending "since the

19th century."

According to a New York Times

report, different groups would be nervous that a convention summoned to

address only one issue might propose a wholesale revision of the entire

Constitution, possibly limiting "provisions they hold dear." Such groups include the American Civil Liberties Union, the John Birch Society, the National Organization for Women, the Gun Owners Clubs of America and conservative advocate Phyllis Schlafly. Accordingly, they are opposed to the idea of a second convention. Lawrence Lessig

countered that the requirement of having 38 states ratify any proposed

revision—three-quarters of all state legislatures—meant that any extreme

proposals would be blocked, since either 13 red or 13 blue states could block such a measure.

Language

Constitutional law scholar Laurence Tribe

noted that the language in the current Constitution about how to

implement a second one is "dangerously vague", and that there is a

possibility that the same interests that have corrupted Washington's

politics may have a hand in efforts to rewrite it.

Politicians and scholars who are reluctant to have a second

constitutional convention may insist that all 34 state petitions to

Congress must have an identical wording or otherwise the petitions would

be considered invalid.

It shall also be necessary for one state to initially create a

resolution and subsequently pass; and then this same resolution, which

passes, must circulate among the several states and be approved by the

necessary two thirds before a convention would be held. In other words,

one document would be drawn up and passed by the states that would

state the rules governing such a convention. The Founding Fathers

allowed for such flexibility within the U.S. Constitution.

Particular views

Lawrence Lessig

Harvard Law School professor Lawrence Lessig has argued that a movement to urge state legislatures to call for a constitutional Convention was the best possibility to achieve substantive reform:

But somebody at the convention said that "what if Congress is the problem—what do we do then?" So they set up an alternative path ... that states can call on Congress to call a Convention. The convention, then, proposes the amendments, and those amendments have to pass by three fourths of the states. So, either way, thirty eight states have to ratify an amendment, but the sources of those amendments are different. One is inside, one is outside.

— Lawrence Lessig, 2011

Lessig argued that the ordinary means of politics were not feasible

to solve the problem affecting the United States government because the

incentives corrupting politicians are so powerful. Lessig believes a convention is needed in view of Supreme Court decisions to eliminate most limits on campaign contributions. He quoted congressperson Jim Cooper from Tennessee who remarked that Congress had become a "Farm League for K Street" in the sense that congresspersons were focused on lucrative careers as lobbyists after serving in the Congress, and not on serving the public interest.

He proposed that such a convention be populated by a random drawing of

citizens' names as a way to keep special interests out of the process.

Sanford Levinson

Constitutional scholar and University of Texas Law School professor Sanford Levinson wrote Our Undemocratic Constitution: Where the Constitution Goes Wrong and called for a "wholesale revision of our nation's founding document." Levinson wrote:

We ought to think about it almost literally every day, and then ask, 'Well, to what extent is government organized to realize the noble visions of the preamble?' That the preamble begins, 'We the people.' It's a notion of a people that can engage in self-determination.

— Sanford Levinson, 2006

Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds, in a keynote speech at Harvard Law School,

said the movement for a new convention was a reflection of having in

many ways "the worst political class in our country's history."

Political scientist Larry Sabato believes a second convention is necessary since "piecemeal amendments" have not been working.

Sabato argued that America needs a "grand meeting of clever and

high-minded people to draw up a new, improved constitution better suited

to the 21st century."

Author Scott Turow

sees risks with a possible convention but believes it may be the only

possible way to undo how campaign money has undermined the "one-man

one-vote" premise.

Few new constitutions are modeled along the lines of the U.S. one, according to a study by David Law of Washington University. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

views the United States Constitution as more of a relic of the 18th

century rather than as a model for new constitutions, and she suggested

in 2014 that a nation seeking a new constitution might find a better

model by examining the Constitution of South Africa (1997), the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) and the European Convention on Human Rights (1950):

I would not look to the United States Constitution if I were drafting a constitution in the year 2012.— Ruth Bader Ginsburg, 2012