Computer network

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A computer network or data network is a telecommunications network that allows computers to exchange data. In computer networks, networked computing devices pass data to each other along data connections. The connections (network links) between nodes are established using either cable media or wireless media. The best-known computer network is the Internet.

Network computer devices that originate, route and terminate the data are called network nodes.[1] Nodes can include hosts such as personal computers, phones, servers as well as networking hardware. Two such devices are said to be networked together when one device is able to exchange information with the other device, whether or not they have a direct connection to each other.

Computer networks support applications such as access to the World Wide Web, shared use of application and storage servers, printers, and fax machines, and use of email and instant messaging applications. Computer networks differ in the physical media used to transmit their signals, the communications protocols to organize network traffic, the network's size, topology and organizational intent.

The following is a chronology of significant computer network developments:

A computer network facilitates interpersonal communications allowing people to communicate efficiently and easily via email, instant messaging, chat rooms, telephone, video telephone calls, and video conferencing. Providing access to information on shared storage devices is an important feature of many networks. A network allows sharing of files, data, and other types of information giving authorized users the ability to access information stored on other computers on the network. A network allows sharing of network and computing resources. Users may access and use resources provided by devices on the network, such as printing a document on a shared network printer. Distributed computing uses computing resources across a network to accomplish tasks. A computer network may be used by computer Crackers to deploy computer viruses or computer worms on devices connected to the network, or to prevent these devices from accessing the network (denial of service). A complex computer network may be difficult to set up. It may be costly to set up an effective computer network in a large organization.

A network packet is a formatted unit of data (a list of bits or bytes) carried by a packet-switched network. Computer communications links that do not support packets, such as traditional point-to-point telecommunications links, simply transmit data as a bit stream. When data is formatted into packets, the bandwidth of the communication medium can be better shared among users than if the network were circuit switched.

A packet consists of two kinds of data: control information and user data (also known as payload). The control information provides data the network needs to deliver the user data, for example: source and destination network addresses, error detection codes, and sequencing information. Typically, control information is found in packet headers and trailers, with payload data in between.

A widely adopted family of communication media used in local area network (LAN) technology is collectively known as Ethernet. The media and protocol standards that enable communication between networked devices over Ethernet are defined by IEEE 802.3. Ethernet transmit data over both copper and fiber cables. Wireless LAN standards (e.g. those defined by IEEE 802.11) use radio waves, or others use infrared signals as a transmission medium. Power line communication uses a building's power cabling to transmit data.

The orders of the following wired technologies are, roughly, from slowest to fastest transmission speed.

A network interface controller (NIC) is computer hardware that provides a computer with the ability to access the transmission media, and has the ability to process low-level network information. For example the NIC may have a connector for accepting a cable, or an aerial for wireless transmission and reception, and the associated circuitry.

The NIC responds to traffic addressed to a network address for either the NIC or the computer as a whole.

In Ethernet networks, each network interface controller has a unique Media Access Control (MAC) address—usually stored in the controller's permanent memory. To avoid address conflicts between network devices, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) maintains and administers MAC address uniqueness. The size of an Ethernet MAC address is six octets. The three most significant octets are reserved to identify NIC manufacturers. These manufacturers, using only their assigned prefixes, uniquely assign the three least-significant octets of every Ethernet interface they produce.

Ethernet configurations, repeaters are required for cable that runs longer than 100 meters. With fiber optics, repeaters can be tens or even hundreds of kilometers apart.

A repeater with multiple ports is known as a hub. Repeaters work on the physical layer of the OSI model. Repeaters require a small amount of time to regenerate the signal. This can cause a propagation delay that affects network performance. As a result, many network architectures limit the number of repeaters that can be used in a row, e.g., the Ethernet 5-4-3 rule.

Hubs have been mostly obsoleted by modern switches; but repeaters are used for long distance links, notably undersea cabling.

Bridges come in three basic types:

Multi-layer switches are capable of routing based on layer 3 addressing or additional logical levels. The term switch is often used loosely to include devices such as routers and bridges, as well as devices that may distribute traffic based on load or based on application content (e.g., a Web URL identifier).

A router is an internetworking device that forwards packets between networks by processing the routing information included in the packet or datagram (Internet protocol information from layer 3).

The routing information is often processed in conjunction with the routing table (or forwarding table). A router uses its routing table to determine where to forward packets. (A destination in a routing table can include a "null" interface, also known as the "black hole" interface because data can go into it, however, no further processing is done for said data.)

Common layouts are:

An overlay network is a virtual computer network that is built on top of another network. Nodes in the overlay network are connected by virtual or logical links. Each link corresponds to a path, perhaps through many physical links, in the underlying network. The topology of the overlay network may (and often does) differ from that of the underlying one. For example, many peer-to-peer networks are overlay networks. They are organized as nodes of a virtual system of links that run on top of the Internet.[10]

Overlay networks have been around since the invention of networking when computer systems were connected over telephone lines using modems, before any data network existed.

The most striking example of an overlay network is the Internet itself. The Internet itself was initially built as an overlay on the telephone network.[10] Even today, at the network layer, each node can reach any other by a direct connection to the desired IP address, thereby creating a fully connected network. The underlying network, however, is composed of a mesh-like interconnect of sub-networks of varying topologies (and technologies). Address resolution and routing are the means that allow mapping of a fully connected IP overlay network to its underlying network.

Another example of an overlay network is a distributed hash table, which maps keys to nodes in the network. In this case, the underlying network is an IP network, and the overlay network is a table (actually a map) indexed by keys.

Overlay networks have also been proposed as a way to improve Internet routing, such as through quality of service guarantees to achieve higher-quality streaming media. Previous proposals such as IntServ, DiffServ, and IP Multicast have not seen wide acceptance largely because they require modification of all routers in the network.[citation needed] On the other hand, an overlay network can be incrementally deployed on end-hosts running the overlay protocol software, without cooperation from Internet service providers. The overlay network has no control over how packets are routed in the underlying network between two overlay nodes, but it can control, for example, the sequence of overlay nodes that a message traverses before it reaches its destination.

For example, Akamai Technologies manages an overlay network that provides reliable, efficient content delivery (a kind of multicast). Academic research includes end system multicast,[11] resilient routing and quality of service studies, among others.

A communications protocol is a set of rules for exchanging information over network links. In a protocol stack (also see the OSI model), each protocol leverages the services of the protocol below it. An important example of a protocol stack is HTTP running over TCP over IP over IEEE 802.11. (TCP and IP are members of the Internet Protocol Suite. IEEE 802.11 is a member of the Ethernet protocol suite.) This stack is used between the wireless router and the home user's personal computer when the user is surfing the web.

Whilst the use of protocol layering is today ubiquitous across the field of computer networking, it has been historically criticized by many researchers[12] for two principle reasons. Firstly, abstracting the protocol stack in this way may cause a higher layer to duplicate functionality of a lower layer, a prime example being error recovery on both a per-link basis and an end-to-end basis.[13] Secondly, it is common that a protocol implementation at one layer may require data, state or addressing information that is only present at another layer, thus defeating the point of separating the layers in the first place. For example, TCP uses the ECN field in the IPv4 header as an indication of congestion; IP is a network layer protocol whereas TCP is a transport layer protocol.

Communication protocols have various characteristics. They may be connection-oriented or connectionless, they may use circuit mode or packet switching, and they may use hierarchical addressing or flat addressing.

There are many communication protocols, a few of which are described below.

While the role of ATM is diminishing in favor of next-generation networks, it still plays a role in the last mile, which is the connection between an Internet service provider and the home user. For an interesting write-up of the technologies involved, including the deep stacking of communications protocols used, see.[14]

A LAN is depicted in the accompanying diagram. All interconnected devices use the network layer (layer 3) to handle multiple subnets (represented by different colors). Those inside the library have 10/100 Mbit/s Ethernet connections to the user device and a Gigabit Ethernet connection to the central router. They could be called Layer 3 switches, because they only have Ethernet interfaces and support the Internet Protocol. It might be more correct to call them access routers, where the router at the top is a distribution router that connects to the Internet and to the academic networks' customer access routers.

The defining characteristics of a LAN, in contrast to a wide area network (WAN), include higher data transfer rates, limited geographic range, and lack of reliance on leased lines to provide connectivity. Current Ethernet or other IEEE 802.3 LAN technologies operate at data transfer rates up to 10 Gbit/s. The IEEE investigates the standardization of 40 and 100 Gbit/s rates.[17] A LAN can be connected to a WAN using a router.

For example, a university campus network is likely to link a variety of campus buildings to connect academic colleges or departments, the library, and student residence halls.

For example, a large company might implement a backbone network to connect departments that are located around the world. The equipment that ties together the departmental networks constitutes the network backbone. When designing a network backbone, network performance and network congestion are critical factors to take into account. Normally, the backbone network's capacity is greater than that of the individual networks connected to it.

Another example of a backbone network is the Internet backbone, which is the set of wide area networks (WANs) and core routers that tie together all networks connected to the Internet.

VPN may have best-effort performance, or may have a defined service level agreement (SLA) between the VPN customer and the VPN service provider. Generally, a VPN has a topology more complex than point-to-point.

These other entities are not necessarily trusted from a security standpoint. Network connection to an extranet is often, but not always, implemented via WAN technology.

The Internet is the largest example of an internetwork. It is a global system of interconnected governmental, academic, corporate, public, and private computer networks. It is based on the networking technologies of the Internet Protocol Suite. It is the successor of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) developed by DARPA of the United States Department of Defense. The Internet is also the communications backbone underlying the World Wide Web (WWW).

Participants in the Internet use a diverse array of methods of several hundred documented, and often standardized, protocols compatible with the Internet Protocol Suite and an addressing system (IP addresses) administered by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority and address registries. Service providers and large enterprises exchange information about the reachability of their address spaces through the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), forming a redundant worldwide mesh of transmission paths.

Darknets are distinct from other distributed peer-to-peer networks as sharing is anonymous (that is, IP addresses are not publicly shared), and therefore users can communicate with little fear of governmental or corporate interference.[20]

Routing is the process of selecting network paths to carry network traffic. Routing is performed for many kinds of networks, including circuit switching networks and packet switched networks.

In packet switched networks, routing directs packet forwarding (the transit of logically addressed network packets from their source toward their ultimate destination) through intermediate nodes. Intermediate nodes are typically network hardware devices such as routers, bridges, gateways, firewalls, or switches. General-purpose computers can also forward packets and perform routing, though they are not specialized hardware and may suffer from limited performance. The routing process usually directs forwarding on the basis of routing tables, which maintain a record of the routes to various network destinations. Thus, constructing routing tables, which are held in the router's memory, is very important for efficient routing. Most routing algorithms use only one network path at a time. Multipath routing techniques enable the use of multiple alternative paths.

There are usually multiple routes that can be taken, and to choose between them, different elements can be considered to decide which routes get installed into the routing table, such as (sorted by priority):

The World Wide Web, E-mail,[21] printing and network file sharing are examples of well-known network services. Network services such as DNS (Domain Name System) give names for IP and MAC addresses (people remember names like “nm.lan” better than numbers like “210.121.67.18”),[22] and DHCP to ensure that the equipment on the network has a valid IP address.[23]

Services are usually based on a service protocol that defines the format and sequencing of messages between clients and servers of that network service.

The following list gives examples of network performance measures for a circuit-switched network and one type of packet-switched network, viz. ATM:

Network protocols that use aggressive retransmissions to compensate for packet loss tend to keep systems in a state of network congestion—even after the initial load is reduced to a level that would not normally induce network congestion. Thus, networks using these protocols can exhibit two stable states under the same level of load. The stable state with low throughput is known as congestive collapse.

Modern networks use congestion control and congestion avoidance techniques to try to avoid congestion collapse. These include: exponential backoff in protocols such as 802.11's CSMA/CA and the original Ethernet, window reduction in TCP, and fair queueing in devices such as routers.

Another method to avoid the negative effects of network congestion is implementing priority schemes, so that some packets are transmitted with higher priority than others. Priority schemes do not solve network congestion by themselves, but they help to alleviate the effects of congestion for some services. An example of this is 802.1p. A third method to avoid network congestion is the explicit allocation of network resources to specific flows. One example of this is the use of Contention-Free Transmission Opportunities (CFTXOPs) in the ITU-T G.hn standard, which provides high-speed (up to 1 Gbit/s) Local area networking over existing home wires (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables).

For the Internet RFC 2914 addresses the subject of congestion control in detail.

Computer and network surveillance programs are widespread today, and almost all Internet traffic is or could potentially be monitored for clues to illegal activity.

Surveillance is very useful to governments and law enforcement to maintain social control, recognize and monitor threats, and prevent/investigate criminal activity. With the advent of programs such as the Total Information Awareness program, technologies such as high speed surveillance computers and biometrics software, and laws such as the Communications Assistance For Law Enforcement Act, governments now possess an unprecedented ability to monitor the activities of citizens.[29]

However, many civil rights and privacy groups—such as Reporters Without Borders, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the American Civil Liberties Union—have expressed concern that increasing surveillance of citizens may lead to a mass surveillance society, with limited political and personal freedoms. Fears such as this have led to numerous lawsuits such as Hepting v. AT&T.[29][30] The hacktivist group Anonymous has hacked into government websites in protest of what it considers "draconian surveillance".[31][32]

Examples of end-to-end encryption include PGP for email, OTR for instant messaging, ZRTP for telephony, and TETRA for radio.

Typical server-based communications systems do not include end-to-end encryption. These systems can only guarantee protection of communications between clients and servers, not between the communicating parties themselves. Examples of non-E2EE systems are Google Talk, Yahoo Messenger, Facebook, and Dropbox. Some such systems, for example LavaBit and SecretInk, have even described themselves as offering "end-to-end" encryption when they do not. Some systems that normally offer end-to-end encryption have turned out to contain a back door that subverts negotiation of the encryption key between the communicating parties, for example Skype.

The end-to-end encryption paradigm does not directly address risks at the communications endpoints themselves, such as the technical exploitation of clients, poor quality random number generators, or key escrow. E2EE also does not address traffic analysis, which relates to things such as the identities of the end points and the times and quantities of messages that are sent.

Network administrators can see networks from both physical and logical perspectives. The physical perspective involves geographic locations, physical cabling, and the network elements (e.g., routers, bridges and application layer gateways) that interconnect the physical media. Logical networks, called, in the TCP/IP architecture, subnets, map onto one or more physical media. For example, a common practice in a campus of buildings is to make a set of LAN cables in each building appear to be a common subnet, using virtual LAN (VLAN) technology.

Both users and administrators are aware, to varying extents, of the trust and scope characteristics of a network. Again using TCP/IP architectural terminology, an intranet is a community of interest under private administration usually by an enterprise, and is only accessible by authorized users (e.g. employees).[33] Intranets do not have to be connected to the Internet, but generally have a limited connection. An extranet is an extension of an intranet that allows secure communications to users outside of the intranet (e.g. business partners, customers).[33]

Unofficially, the Internet is the set of users, enterprises, and content providers that are interconnected by Internet Service Providers (ISP). From an engineering viewpoint, the Internet is the set of subnets, and aggregates of subnets, which share the registered IP address space and exchange information about the reachability of those IP addresses using the Border Gateway Protocol. Typically, the human-readable names of servers are translated to IP addresses, transparently to users, via the directory function of the Domain Name System (DNS).

Over the Internet, there can be business-to-business (B2B), business-to-consumer (B2C) and consumer-to-consumer (C2C) communications. When money or sensitive information is exchanged, the communications are apt to be protected by some form of communications security mechanism. Intranets and extranets can be securely superimposed onto the Internet, without any access by general Internet users and administrators, using secure Virtual Private Network (VPN) technology.

Network computer devices that originate, route and terminate the data are called network nodes.[1] Nodes can include hosts such as personal computers, phones, servers as well as networking hardware. Two such devices are said to be networked together when one device is able to exchange information with the other device, whether or not they have a direct connection to each other.

Computer networks support applications such as access to the World Wide Web, shared use of application and storage servers, printers, and fax machines, and use of email and instant messaging applications. Computer networks differ in the physical media used to transmit their signals, the communications protocols to organize network traffic, the network's size, topology and organizational intent.

History

Today, computer networks are the core of modern communication. All modern aspects of the public switched telephone network (PSTN) are computer-controlled. Telephony increasingly runs over the Internet Protocol, although not necessarily the public Internet. The scope of communication has increased significantly in the past decade. This boom in communications would not have been possible without the progressively advancing computer network. Computer networks, and the technologies that make communication between networked computers possible, continue to drive computer hardware, software, and peripherals industries. The expansion of related industries is mirrored by growth in the numbers and types of people using networks, from the researcher to the home user.The following is a chronology of significant computer network developments:

- In the late 1950s, early networks of communicating computers included the military radar system Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE).

- In 1960, the commercial airline reservation system semi-automatic business research environment (SABRE) went online with two connected mainframes.

- In 1962, J.C.R. Licklider developed a working group he called the "Intergalactic Computer Network", a precursor to the ARPANET, at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA).

- In 1964, researchers at Dartmouth developed the Dartmouth Time Sharing System for distributed users of large computer systems. The same year, at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a research group supported by General Electric and Bell Labs used a computer to route and manage telephone connections.

- Throughout the 1960s, Leonard Kleinrock, Paul Baran, and Donald Davies independently developed network systems that used packets to transfer information between computers over a network.

- In 1965, Thomas Marill and Lawrence G. Roberts created the first wide area network (WAN). This was an immediate precursor to the ARPANET, of which Roberts became program manager.

- Also in 1965, the first widely used telephone switch that implemented true computer control was introduced by Western Electric.

- In 1969, the University of California at Los Angeles, the Stanford Research Institute, the University of California at Santa Barbara, and the University of Utah were connected as the beginning of the ARPANET network using 50 kbit/s circuits.[2]

- In 1972, commercial services using X.25 were deployed, and later used as an underlying infrastructure for expanding TCP/IP networks.

- In 1973, Robert Metcalfe wrote a formal memo at Xerox PARC describing Ethernet, a networking system that was based on the Aloha network, developed in the 1960s by Norman Abramson and colleagues at the University of Hawaii. In July 1976, Robert Metcalfe and David Boggs published their paper "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks"[3] and collaborated on several patents received in 1977 and 1978. In 1979, Robert Metcalfe pursued making Ethernet an open standard.[4]

- In 1976, John Murphy of Datapoint Corporation created ARCNET, a token-passing network first used to share storage devices.

- In 1995, the transmission speed capacity for Ethernet was increased from 10 Mbit/s to 100 Mbit/s. By 1998, Ethernet supported transmission speeds of a Gigabit. The ability of Ethernet to scale easily (such as quickly adapting to support new fiber optic cable speeds) is a contributing factor to its continued use today.[4]

Properties

Computer networking may be considered a branch of electrical engineering, telecommunications, computer science, information technology or computer engineering, since it relies upon the theoretical and practical application of the related disciplines.A computer network facilitates interpersonal communications allowing people to communicate efficiently and easily via email, instant messaging, chat rooms, telephone, video telephone calls, and video conferencing. Providing access to information on shared storage devices is an important feature of many networks. A network allows sharing of files, data, and other types of information giving authorized users the ability to access information stored on other computers on the network. A network allows sharing of network and computing resources. Users may access and use resources provided by devices on the network, such as printing a document on a shared network printer. Distributed computing uses computing resources across a network to accomplish tasks. A computer network may be used by computer Crackers to deploy computer viruses or computer worms on devices connected to the network, or to prevent these devices from accessing the network (denial of service). A complex computer network may be difficult to set up. It may be costly to set up an effective computer network in a large organization.

Network packet

Most information in computer networks is carried in packets.A network packet is a formatted unit of data (a list of bits or bytes) carried by a packet-switched network. Computer communications links that do not support packets, such as traditional point-to-point telecommunications links, simply transmit data as a bit stream. When data is formatted into packets, the bandwidth of the communication medium can be better shared among users than if the network were circuit switched.

A packet consists of two kinds of data: control information and user data (also known as payload). The control information provides data the network needs to deliver the user data, for example: source and destination network addresses, error detection codes, and sequencing information. Typically, control information is found in packet headers and trailers, with payload data in between.

Network topology

The physical layout of a network is usually less important than the topology that connects network nodes. Most diagrams that describe a physical network are therefore topological, rather than geographic. The symbols on these diagrams usually denote network links and network nodes.Network links

The communication media used to link devices to form a computer network include electrical cable (HomePNA, power line communication, G.hn), optical fiber (fiber-optic communication), and radio waves (wireless networking). In the OSI model, these are defined at layers 1 and 2 — the physical layer and the data link layer.A widely adopted family of communication media used in local area network (LAN) technology is collectively known as Ethernet. The media and protocol standards that enable communication between networked devices over Ethernet are defined by IEEE 802.3. Ethernet transmit data over both copper and fiber cables. Wireless LAN standards (e.g. those defined by IEEE 802.11) use radio waves, or others use infrared signals as a transmission medium. Power line communication uses a building's power cabling to transmit data.

Wired technologies

Fiber optic cables are used to transmit light from one computer/network node to another

The orders of the following wired technologies are, roughly, from slowest to fastest transmission speed.

- Twisted pair wire is the most widely used medium for all telecommunication. Twisted-pair cabling consist of copper wires that are twisted into pairs. Ordinary telephone wires consist of two insulated copper wires twisted into pairs. Computer network cabling (wired Ethernet as defined by IEEE 802.3) consists of 4 pairs of copper cabling that can be utilized for both voice and data transmission. The use of two wires twisted together helps to reduce crosstalk and electromagnetic induction. The transmission speed ranges from 2 million bits per second to 10 billion bits per second. Twisted pair cabling comes in two forms: unshielded twisted pair (UTP) and shielded twisted-pair (STP). Each form comes in several category ratings, designed for use in various scenarios.

- Coaxial cable is widely used for cable television systems, office buildings, and other work-sites for local area networks. The cables consist of copper or aluminum wire surrounded by an insulating layer (typically a flexible material with a high dielectric constant), which itself is surrounded by a conductive layer. The insulation helps minimize interference and distortion. Transmission speed ranges from 200 million bits per second to more than 500 million bits per second.

- ITU-T G.hn technology uses existing home wiring (coaxial cable, phone lines and power lines) to create a high-speed (up to 1 Gigabit/s) local area network.

- An optical fiber is a glass fiber. It carries pulses of light that represent data. Some advantages of optical fibers over metal wires are very low transmission loss and immunity from electrical interference. Optical fibers can simultaneously carry multiple wavelengths of light, which greatly increases the rate that data can be sent, and helps enable data rates of up to trillions of bits per second. Optic fibers can be used for long runs of cable carrying very high data rates, and are used for undersea cables to interconnect continents.

- Price is a main factor distinguishing wired- and wireless-technology options in a business. Wireless options command a price premium that can make purchasing wired computers, printers and other devices a financial benefit. Before making the decision to purchase hard-wired technology products, a review of the restrictions and limitations of the selections is necessary. Business and employee needs may override any cost considerations.[5]

Wireless technologies[edit]

- Terrestrial microwave – Terrestrial microwave communication uses Earth-based transmitters and receivers resembling satellite dishes. Terrestrial microwaves are in the low-gigahertz range, which limits all communications to line-of-sight. Relay stations are spaced approximately 48 km (30 mi) apart.

- Communications satellites – Satellites communicate via microwave radio waves, which are not deflected by the Earth's atmosphere. The satellites are stationed in space, typically in geosynchronous orbit 35,400 km (22,000 mi) above the equator. These Earth-orbiting systems are capable of receiving and relaying voice, data, and TV signals.

- Cellular and PCS systems use several radio communications technologies. The systems divide the region covered into multiple geographic areas. Each area has a low-power transmitter or radio relay antenna device to relay calls from one area to the next area.

- Radio and spread spectrum technologies – Wireless local area networks use a high-frequency radio technology similar to digital cellular and a low-frequency radio technology. Wireless LANs use spread spectrum technology to enable communication between multiple devices in a limited area. IEEE 802.11 defines a common flavor of open-standards wireless radio-wave technology known as Wifi.

- Free-space optical communication uses visible or invisible light for communications. In most cases, line-of-sight propagation is used, which limits the physical positioning of communicating devices.

Exotic technologies

There have been various attempts at transporting data over exotic media:- IP over Avian Carriers was a humorous April fool's Request for Comments, issued as RFC 1149. It was implemented in real life in 2001.[6]

- Extending the Internet to interplanetary dimensions via radio waves.[7]

Network nodes

Apart from the physical communications media described above, networks comprise additional basic system building blocks, such as network interface controller (NICs), repeaters, hubs, bridges, switches, routers, modems, and firewalls.Network interfaces

An ATM network interface in the form of an accessory card. A lot of network interfaces are built-in.

A network interface controller (NIC) is computer hardware that provides a computer with the ability to access the transmission media, and has the ability to process low-level network information. For example the NIC may have a connector for accepting a cable, or an aerial for wireless transmission and reception, and the associated circuitry.

The NIC responds to traffic addressed to a network address for either the NIC or the computer as a whole.

In Ethernet networks, each network interface controller has a unique Media Access Control (MAC) address—usually stored in the controller's permanent memory. To avoid address conflicts between network devices, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) maintains and administers MAC address uniqueness. The size of an Ethernet MAC address is six octets. The three most significant octets are reserved to identify NIC manufacturers. These manufacturers, using only their assigned prefixes, uniquely assign the three least-significant octets of every Ethernet interface they produce.

Repeaters and hubs

A repeater is an electronic device that receives a network signal, cleans it of unnecessary noise, and regenerates it. The signal is retransmitted at a higher power level, or to the other side of an obstruction, so that the signal can cover longer distances without degradation. In most twisted pairEthernet configurations, repeaters are required for cable that runs longer than 100 meters. With fiber optics, repeaters can be tens or even hundreds of kilometers apart.

A repeater with multiple ports is known as a hub. Repeaters work on the physical layer of the OSI model. Repeaters require a small amount of time to regenerate the signal. This can cause a propagation delay that affects network performance. As a result, many network architectures limit the number of repeaters that can be used in a row, e.g., the Ethernet 5-4-3 rule.

Hubs have been mostly obsoleted by modern switches; but repeaters are used for long distance links, notably undersea cabling.

Bridges

A network bridge connects and filters traffic between two network segments at the data link layer (layer 2) of the OSI model to form a single network. This breaks the network's collision domain but maintains a unified broadcast domain. Network segmentation breaks down a large, congested network into an aggregation of smaller, more efficient networks.Bridges come in three basic types:

- Local bridges: Directly connect LANs

- Remote bridges: Can be used to create a wide area network (WAN) link between LANs. Remote bridges, where the connecting link is slower than the end networks, largely have been replaced with routers.

- Wireless bridges: Can be used to join LANs or connect remote devices to LANs.

Switches

A network switch is a device that forwards and filters OSI layer 2 datagrams between ports based on the MAC addresses in the packets.[8] A switch is distinct from a hub in that it only forwards the frames to the physical ports involved in the communication rather than all ports connected. It can be thought of as a multi-port bridge.[9] It learns to associate physical ports to MAC addresses by examining the source addresses of received frames. If an unknown destination is targeted, the switch broadcasts to all ports but the source. Switches normally have numerous ports, facilitating a star topology for devices, and cascading additional switches.Multi-layer switches are capable of routing based on layer 3 addressing or additional logical levels. The term switch is often used loosely to include devices such as routers and bridges, as well as devices that may distribute traffic based on load or based on application content (e.g., a Web URL identifier).

Routers

A router is an internetworking device that forwards packets between networks by processing the routing information included in the packet or datagram (Internet protocol information from layer 3).

The routing information is often processed in conjunction with the routing table (or forwarding table). A router uses its routing table to determine where to forward packets. (A destination in a routing table can include a "null" interface, also known as the "black hole" interface because data can go into it, however, no further processing is done for said data.)

Modems

Modems (MOdulator-DEModulator) are used to connect network nodes via wire not originally designed for digital network traffic, or for wireless. To do this one or more frequencies are modulated by the digital signal to produce an analog signal that can be tailored to give the required properties for transmission. Modems are commonly used for telephone lines, using a Digital Subscriber Line technology.Firewalls

A firewall is a network device for controlling network security and access rules. Firewalls are typically configured to reject access requests from unrecognized sources while allowing actions from recognized ones. The vital role firewalls play in network security grows in parallel with the constant increase in cyber attacks.Network structure

Network topology is the layout or organizational hierarchy of interconnected nodes of a computer network. Different network topologies can affect throughput, but reliability is often more critical. With many technologies, such as bus networks, a single failure can cause the network to fail entirely. In general the more interconnections there are, the more robust the network is; but the more expensive it is to install.Common layouts

Common layouts are:

- A bus network: all nodes are connected to a common medium along this medium. This was the layout used in the original Ethernet, called 10BASE5 and 10BASE2.

- A star network: all nodes are connected to a special central node. This is the typical layout found in a Wireless LAN, where each wireless client connects to the central Wireless access point.

- A ring network: each node is connected to its left and right neighbour node, such that all nodes are connected and that each node can reach each other node by traversing nodes left- or rightwards. The Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI) made use of such a topology.

- A mesh network: each node is connected to an arbitrary number of neighbours in such a way that there is at least one traversal from any node to any other.

- A fully connected network: each node is connected to every other node in the network.

- A tree network: nodes are arranged hierarchically.

Overlay network

An overlay network is a virtual computer network that is built on top of another network. Nodes in the overlay network are connected by virtual or logical links. Each link corresponds to a path, perhaps through many physical links, in the underlying network. The topology of the overlay network may (and often does) differ from that of the underlying one. For example, many peer-to-peer networks are overlay networks. They are organized as nodes of a virtual system of links that run on top of the Internet.[10]

Overlay networks have been around since the invention of networking when computer systems were connected over telephone lines using modems, before any data network existed.

The most striking example of an overlay network is the Internet itself. The Internet itself was initially built as an overlay on the telephone network.[10] Even today, at the network layer, each node can reach any other by a direct connection to the desired IP address, thereby creating a fully connected network. The underlying network, however, is composed of a mesh-like interconnect of sub-networks of varying topologies (and technologies). Address resolution and routing are the means that allow mapping of a fully connected IP overlay network to its underlying network.

Another example of an overlay network is a distributed hash table, which maps keys to nodes in the network. In this case, the underlying network is an IP network, and the overlay network is a table (actually a map) indexed by keys.

Overlay networks have also been proposed as a way to improve Internet routing, such as through quality of service guarantees to achieve higher-quality streaming media. Previous proposals such as IntServ, DiffServ, and IP Multicast have not seen wide acceptance largely because they require modification of all routers in the network.[citation needed] On the other hand, an overlay network can be incrementally deployed on end-hosts running the overlay protocol software, without cooperation from Internet service providers. The overlay network has no control over how packets are routed in the underlying network between two overlay nodes, but it can control, for example, the sequence of overlay nodes that a message traverses before it reaches its destination.

For example, Akamai Technologies manages an overlay network that provides reliable, efficient content delivery (a kind of multicast). Academic research includes end system multicast,[11] resilient routing and quality of service studies, among others.

Communications protocols

A communications protocol is a set of rules for exchanging information over network links. In a protocol stack (also see the OSI model), each protocol leverages the services of the protocol below it. An important example of a protocol stack is HTTP running over TCP over IP over IEEE 802.11. (TCP and IP are members of the Internet Protocol Suite. IEEE 802.11 is a member of the Ethernet protocol suite.) This stack is used between the wireless router and the home user's personal computer when the user is surfing the web.

Whilst the use of protocol layering is today ubiquitous across the field of computer networking, it has been historically criticized by many researchers[12] for two principle reasons. Firstly, abstracting the protocol stack in this way may cause a higher layer to duplicate functionality of a lower layer, a prime example being error recovery on both a per-link basis and an end-to-end basis.[13] Secondly, it is common that a protocol implementation at one layer may require data, state or addressing information that is only present at another layer, thus defeating the point of separating the layers in the first place. For example, TCP uses the ECN field in the IPv4 header as an indication of congestion; IP is a network layer protocol whereas TCP is a transport layer protocol.

Communication protocols have various characteristics. They may be connection-oriented or connectionless, they may use circuit mode or packet switching, and they may use hierarchical addressing or flat addressing.

There are many communication protocols, a few of which are described below.

Ethernet

Ethernet is a family of protocols used in LANs, described by a set of standards together called IEEE 802 published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. It has a flat addressing scheme. It operates mostly at levels 1 and 2 of the OSI model. For home users today, the most well-known member of this protocol family is IEEE 802.11, otherwise known as Wireless LAN (WLAN). The complete IEEE 802 protocol suite provides a diverse set of networking capabilities. For example, MAC bridging (IEEE 802.1D) deals with the routing of Ethernet packets using a Spanning Tree Protocol, IEEE 802.1Q describes VLANs, and IEEE 802.1X defines a port-based Network Access Control protocol, which forms the basis for the authentication mechanisms used in VLANs (but it is also found in WLANs) – it is what the home user sees when the user has to enter a "wireless access key".Internet Protocol Suite

The Internet Protocol Suite, also called TCP/IP, is the foundation of all modern networking. It offers connection-less as well as connection-oriented services over an inherently unreliable network traversed by data-gram transmission at the Internet protocol (IP) level. At its core, the protocol suite defines the addressing, identification, and routing specifications for Internet Protocol Version 4 (IPv4) and for IPv6, the next generation of the protocol with a much enlarged addressing capability.SONET/SDH

Synchronous optical networking (SONET) and Synchronous Digital Hierarchy (SDH) are standardized multiplexing protocols that transfer multiple digital bit streams over optical fiber using lasers. They were originally designed to transport circuit mode communications from a variety of different sources, primarily to support real-time, uncompressed, circuit-switched voice encoded in PCM (Pulse-Code Modulation) format. However, due to its protocol neutrality and transport-oriented features, SONET/SDH also was the obvious choice for transporting Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) frames.Asynchronous Transfer Mode

Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) is a switching technique for telecommunication networks. It uses asynchronous time-division multiplexing and encodes data into small, fixed-sized cells. This differs from other protocols such as the Internet Protocol Suite or Ethernet that use variable sized packets or frames. ATM has similarity with both circuit and packet switched networking. This makes it a good choice for a network that must handle both traditional high-throughput data traffic, and real-time, low-latency content such as voice and video. ATM uses a connection-oriented model in which a virtual circuit must be established between two endpoints before the actual data exchange begins.While the role of ATM is diminishing in favor of next-generation networks, it still plays a role in the last mile, which is the connection between an Internet service provider and the home user. For an interesting write-up of the technologies involved, including the deep stacking of communications protocols used, see.[14]

Geographic scale

A network can be characterized by its physical capacity or its organizational purpose. Use of the network, including user authorization and access rights, differ accordingly.- Personal area network

- Local area network

A LAN is depicted in the accompanying diagram. All interconnected devices use the network layer (layer 3) to handle multiple subnets (represented by different colors). Those inside the library have 10/100 Mbit/s Ethernet connections to the user device and a Gigabit Ethernet connection to the central router. They could be called Layer 3 switches, because they only have Ethernet interfaces and support the Internet Protocol. It might be more correct to call them access routers, where the router at the top is a distribution router that connects to the Internet and to the academic networks' customer access routers.

The defining characteristics of a LAN, in contrast to a wide area network (WAN), include higher data transfer rates, limited geographic range, and lack of reliance on leased lines to provide connectivity. Current Ethernet or other IEEE 802.3 LAN technologies operate at data transfer rates up to 10 Gbit/s. The IEEE investigates the standardization of 40 and 100 Gbit/s rates.[17] A LAN can be connected to a WAN using a router.

- Home area network

- Storage area network

- Campus area network

For example, a university campus network is likely to link a variety of campus buildings to connect academic colleges or departments, the library, and student residence halls.

- Backbone network

For example, a large company might implement a backbone network to connect departments that are located around the world. The equipment that ties together the departmental networks constitutes the network backbone. When designing a network backbone, network performance and network congestion are critical factors to take into account. Normally, the backbone network's capacity is greater than that of the individual networks connected to it.

Another example of a backbone network is the Internet backbone, which is the set of wide area networks (WANs) and core routers that tie together all networks connected to the Internet.

- Metropolitan area network

- Wide area network

- Enterprise private network

- Virtual private network

VPN may have best-effort performance, or may have a defined service level agreement (SLA) between the VPN customer and the VPN service provider. Generally, a VPN has a topology more complex than point-to-point.

- Global area network

Organizational scope

Networks are typically managed by the organizations that own them. Private enterprise networks may use a combination of intranets and extranets. They may also provide network access to the Internet, which has no single owner and permits virtually unlimited global connectivity.Intranets

An intranet is a set of networks that are under the control of a single administrative entity. The intranet uses the IP protocol and IP-based tools such as web browsers and file transfer applications. The administrative entity limits use of the intranet to its authorized users. Most commonly, an intranet is the internal LAN of an organization. A large intranet typically has at least one web server to provide users with organizational information. An intranet is also anything behind the router on a local area network.Extranet

An extranet is a network that is also under the administrative control of a single organization, but supports a limited connection to a specific external network. For example, an organization may provide access to some aspects of its intranet to share data with its business partners or customers.These other entities are not necessarily trusted from a security standpoint. Network connection to an extranet is often, but not always, implemented via WAN technology.

Internetwork

An internetwork is the connection of multiple computer networks via a common routing technology using routers.Internet

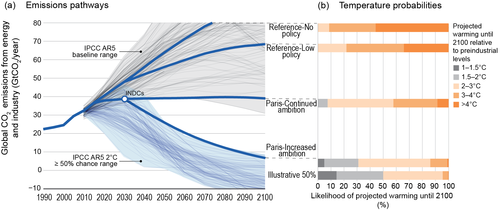

Partial map of the Internet based on the January 15, 2005 data found on opte.org. Each line is drawn between two nodes, representing two IP addresses. The length of the lines are indicative of the delay between those two nodes. This graph represents less than 30% of the Class C networks reachable.

The Internet is the largest example of an internetwork. It is a global system of interconnected governmental, academic, corporate, public, and private computer networks. It is based on the networking technologies of the Internet Protocol Suite. It is the successor of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) developed by DARPA of the United States Department of Defense. The Internet is also the communications backbone underlying the World Wide Web (WWW).

Participants in the Internet use a diverse array of methods of several hundred documented, and often standardized, protocols compatible with the Internet Protocol Suite and an addressing system (IP addresses) administered by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority and address registries. Service providers and large enterprises exchange information about the reachability of their address spaces through the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), forming a redundant worldwide mesh of transmission paths.

Darknet

A Darknet is an overlay network, typically running on the internet, that is only accessible through specialized software. A darknet is an anonymizing network where connections are made only between trusted peers — sometimes called "friends" (F2F)[19] — using non-standard protocols and ports.Darknets are distinct from other distributed peer-to-peer networks as sharing is anonymous (that is, IP addresses are not publicly shared), and therefore users can communicate with little fear of governmental or corporate interference.[20]

Routing

Routing is the process of selecting network paths to carry network traffic. Routing is performed for many kinds of networks, including circuit switching networks and packet switched networks.

In packet switched networks, routing directs packet forwarding (the transit of logically addressed network packets from their source toward their ultimate destination) through intermediate nodes. Intermediate nodes are typically network hardware devices such as routers, bridges, gateways, firewalls, or switches. General-purpose computers can also forward packets and perform routing, though they are not specialized hardware and may suffer from limited performance. The routing process usually directs forwarding on the basis of routing tables, which maintain a record of the routes to various network destinations. Thus, constructing routing tables, which are held in the router's memory, is very important for efficient routing. Most routing algorithms use only one network path at a time. Multipath routing techniques enable the use of multiple alternative paths.

There are usually multiple routes that can be taken, and to choose between them, different elements can be considered to decide which routes get installed into the routing table, such as (sorted by priority):

- Prefix-Length: where longer subnet masks are preferred (independent if it is within a routing protocol or over different routing protocol)

- Metric: where a lower metric/cost is preferred (only valid within one and the same routing protocol)

- Administrative distance: where a lower distance is preferred (only valid between different routing protocols)

Network service

Network services are applications hosted by servers on a computer network, to provide some functionality for members or users of the network, or to help the network itself to operate.The World Wide Web, E-mail,[21] printing and network file sharing are examples of well-known network services. Network services such as DNS (Domain Name System) give names for IP and MAC addresses (people remember names like “nm.lan” better than numbers like “210.121.67.18”),[22] and DHCP to ensure that the equipment on the network has a valid IP address.[23]

Services are usually based on a service protocol that defines the format and sequencing of messages between clients and servers of that network service.

Network performance

Quality of service

Depending on the installation requirements, network performance is usually measured by the quality of service of a telecommunications product. The parameters that affect this typically can include throughput, jitter, bit error rate and latency.The following list gives examples of network performance measures for a circuit-switched network and one type of packet-switched network, viz. ATM:

- Circuit-switched networks: In circuit switched networks, network performance is synonymous with the grade of service. The number of rejected calls is a measure of how well the network is performing under heavy traffic loads.[24] Other types of performance measures can include the level of noise and echo.

- ATM: In an Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM) network, performance can be measured by line rate, quality of service (QoS), data throughput, connect time, stability, technology, modulation technique and modem enhancements.[25]

Network congestion

Network congestion occurs when a link or node is carrying so much data that its quality of service deteriorates. Typical effects include queueing delay, packet loss or the blocking of new connections. A consequence of these latter two is that incremental increases in offered load lead either only to small increase in network throughput, or to an actual reduction in network throughput.Network protocols that use aggressive retransmissions to compensate for packet loss tend to keep systems in a state of network congestion—even after the initial load is reduced to a level that would not normally induce network congestion. Thus, networks using these protocols can exhibit two stable states under the same level of load. The stable state with low throughput is known as congestive collapse.

Modern networks use congestion control and congestion avoidance techniques to try to avoid congestion collapse. These include: exponential backoff in protocols such as 802.11's CSMA/CA and the original Ethernet, window reduction in TCP, and fair queueing in devices such as routers.

Another method to avoid the negative effects of network congestion is implementing priority schemes, so that some packets are transmitted with higher priority than others. Priority schemes do not solve network congestion by themselves, but they help to alleviate the effects of congestion for some services. An example of this is 802.1p. A third method to avoid network congestion is the explicit allocation of network resources to specific flows. One example of this is the use of Contention-Free Transmission Opportunities (CFTXOPs) in the ITU-T G.hn standard, which provides high-speed (up to 1 Gbit/s) Local area networking over existing home wires (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables).

For the Internet RFC 2914 addresses the subject of congestion control in detail.

Network resilience

Network resilience is "the ability to provide and maintain an acceptable level of service in the face of faults and challenges to normal operation.”[27]Security

Network security

Network security consists of provisions and policies adopted by the network administrator to prevent and monitor unauthorized access, misuse, modification, or denial of the computer network and its network-accessible resources.[28] Network security is the authorization of access to data in a network, which is controlled by the network administrator. Users are assigned an ID and password that allows them access to information and programs within their authority. Network security is used on a variety of computer networks, both public and private, to secure daily transactions and communications among businesses, government agencies and individuals.Network surveillance

Network surveillance is the monitoring of data being transferred over computer networks such as the Internet. The monitoring is often done surreptitiously and may be done by or at the behest of governments, by corporations, criminal organizations, or individuals. It may or may not be legal and may or may not require authorization from a court or other independent agency.Computer and network surveillance programs are widespread today, and almost all Internet traffic is or could potentially be monitored for clues to illegal activity.

Surveillance is very useful to governments and law enforcement to maintain social control, recognize and monitor threats, and prevent/investigate criminal activity. With the advent of programs such as the Total Information Awareness program, technologies such as high speed surveillance computers and biometrics software, and laws such as the Communications Assistance For Law Enforcement Act, governments now possess an unprecedented ability to monitor the activities of citizens.[29]

However, many civil rights and privacy groups—such as Reporters Without Borders, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and the American Civil Liberties Union—have expressed concern that increasing surveillance of citizens may lead to a mass surveillance society, with limited political and personal freedoms. Fears such as this have led to numerous lawsuits such as Hepting v. AT&T.[29][30] The hacktivist group Anonymous has hacked into government websites in protest of what it considers "draconian surveillance".[31][32]

End to end encryption

End-to-end encryption (E2EE) is a digital communications paradigm of uninterrupted protection of data traveling between two communicating parties. It involves the originating party encrypting data so only the intended recipient can decrypt it, with no dependency on third parties. End-to-end encryption prevents intermediaries, such as Internet providers or application service providers, from discovering or tampering with communications. End-to-end encryption generally protects both confidentiality and integrity.Examples of end-to-end encryption include PGP for email, OTR for instant messaging, ZRTP for telephony, and TETRA for radio.

Typical server-based communications systems do not include end-to-end encryption. These systems can only guarantee protection of communications between clients and servers, not between the communicating parties themselves. Examples of non-E2EE systems are Google Talk, Yahoo Messenger, Facebook, and Dropbox. Some such systems, for example LavaBit and SecretInk, have even described themselves as offering "end-to-end" encryption when they do not. Some systems that normally offer end-to-end encryption have turned out to contain a back door that subverts negotiation of the encryption key between the communicating parties, for example Skype.

The end-to-end encryption paradigm does not directly address risks at the communications endpoints themselves, such as the technical exploitation of clients, poor quality random number generators, or key escrow. E2EE also does not address traffic analysis, which relates to things such as the identities of the end points and the times and quantities of messages that are sent.

Views of networks

Users and network administrators typically have different views of their networks. Users can share printers and some servers from a workgroup, which usually means they are in the same geographic location and are on the same LAN, whereas a Network Administrator is responsible to keep that network up and running. A community of interest has less of a connection of being in a local area, and should be thought of as a set of arbitrarily located users who share a set of servers, and possibly also communicate via peer-to-peer technologies.Network administrators can see networks from both physical and logical perspectives. The physical perspective involves geographic locations, physical cabling, and the network elements (e.g., routers, bridges and application layer gateways) that interconnect the physical media. Logical networks, called, in the TCP/IP architecture, subnets, map onto one or more physical media. For example, a common practice in a campus of buildings is to make a set of LAN cables in each building appear to be a common subnet, using virtual LAN (VLAN) technology.

Both users and administrators are aware, to varying extents, of the trust and scope characteristics of a network. Again using TCP/IP architectural terminology, an intranet is a community of interest under private administration usually by an enterprise, and is only accessible by authorized users (e.g. employees).[33] Intranets do not have to be connected to the Internet, but generally have a limited connection. An extranet is an extension of an intranet that allows secure communications to users outside of the intranet (e.g. business partners, customers).[33]

Unofficially, the Internet is the set of users, enterprises, and content providers that are interconnected by Internet Service Providers (ISP). From an engineering viewpoint, the Internet is the set of subnets, and aggregates of subnets, which share the registered IP address space and exchange information about the reachability of those IP addresses using the Border Gateway Protocol. Typically, the human-readable names of servers are translated to IP addresses, transparently to users, via the directory function of the Domain Name System (DNS).

Over the Internet, there can be business-to-business (B2B), business-to-consumer (B2C) and consumer-to-consumer (C2C) communications. When money or sensitive information is exchanged, the communications are apt to be protected by some form of communications security mechanism. Intranets and extranets can be securely superimposed onto the Internet, without any access by general Internet users and administrators, using secure Virtual Private Network (VPN) technology.