From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Purple glow in its plasma state

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

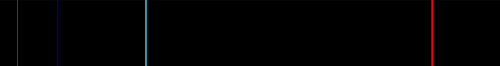

Spectral lines of hydrogen

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, symbol | hydrogen, H | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈhaɪdrədʒən/[1] HY-drə-jən |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | colorless gas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hydrogen in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight | 1.008[2] (1.00784–1.00811)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | diatomic nonmetal, could be considered metalloid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, block | group 1, s-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | 1s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| per shell | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Color | colorless | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | gas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 13.99 K (−259.16 °C, −434.49 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 20.271 K (−252.879 °C, −423.182 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density at stp (0 °C and 101.325 kPa) | 0.08988 g·L−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid, at m.p. | 0.07 g·cm−3 (solid: 0.0763 g·cm−3)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid, at b.p. | 0.07099 g·cm−3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 13.8033 K, 7.041 kPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 32.938 K, 1.2858 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (H2) 0.117 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | (H2) 0.904 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (H2) 28.836 J·mol−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 1, −1 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 1312.0 kJ·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 31±5 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 120 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellanea | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 1310 m·s−1 (gas, 27 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.1805 W·m−1·K−1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Registry Number | 1333-74-0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Henry Cavendish[6][7] (1766) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | Antoine Lavoisier[8] (1783) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Most stable isotopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

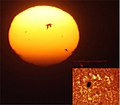

Hydrogen is a chemical element with chemical symbol H and atomic number 1. With an atomic weight of 1.00794 u, hydrogen is the lightest element on the periodic table. Its monatomic form (H) is the most abundant chemical substance in the universe, constituting roughly 75% of all baryonic mass.[9][note 1] Non-remnant stars are mainly composed of hydrogen in its plasma state. The most common isotope of hydrogen, termed protium (name rarely used, symbol 1H), has a single proton and zero neutrons.

The universal emergence of atomic hydrogen first occurred during the recombination epoch. At standard temperature and pressure, hydrogen is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, nonmetallic, highly combustible diatomic gas with the molecular formula H2. Since hydrogen readily forms covalent compounds with most non-metallic elements, most of the hydrogen on Earth exists in molecular forms such as in the form of water or organic compounds. Hydrogen plays a particularly important role in acid–base reactions as many acid-base reactions involve the exchange of protons between soluble molecules. In ionic compounds, hydrogen can take the form of a negative charge (i.e., anion) known as a hydride, or as a positively charged (i.e., cation) species denoted by the symbol H+. The hydrogen cation is written as though composed of a bare proton, but in reality, hydrogen cations in ionic compounds are always more complex species than that would suggest. As the only neutral atom for which the Schrödinger equation can be solved analytically, study of the energetics and bonding of the hydrogen atom has played a key role in the development of quantum mechanics.

Hydrogen gas was first artificially produced in the early 16th century, via the mixing of metals with acids. In 1766–81, Henry Cavendish was the first to recognize that hydrogen gas was a discrete substance,[10] and that it produces water when burned, a property which later gave it its name: in Greek, hydrogen means "water-former".

Industrial production is mainly from the steam reforming of natural gas, and less often from more energy-intensive hydrogen production methods like the electrolysis of water.[11] Most hydrogen is employed near its production site, with the two largest uses being fossil fuel processing (e.g., hydrocracking) and ammonia production, mostly for the fertilizer market.

Hydrogen is a concern in metallurgy as it can embrittle many metals,[12] complicating the design of pipelines and storage tanks.[13]

Properties

Combustion

The Space Shuttle Main Engine burnt hydrogen with oxygen, producing a nearly invisible flame at full thrust.

Hydrogen gas (dihydrogen or molecular hydrogen)[14] is highly flammable and will burn in air at a very wide range of concentrations between 4% and 75% by volume.[15] The enthalpy of combustion for hydrogen is −286 kJ/mol:[16]

- 2 H2(g) + O2(g) → 2 H2O(l) + 572 kJ (286 kJ/mol)[note 2]

H2 reacts with every oxidizing element. Hydrogen can react spontaneously and violently at room temperature with chlorine and fluorine to form the corresponding hydrogen halides, hydrogen chloride and hydrogen fluoride, which are also potentially dangerous acids.[19]

Electron energy levels

Depiction of a hydrogen atom with size of central proton shown, and the atomic diameter shown as about twice the Bohr model radius (image not to scale)

The ground state energy level of the electron in a hydrogen atom is −13.6 eV, which is equivalent to an ultraviolet photon of roughly 92 nm wavelength.[20]

The energy levels of hydrogen can be calculated fairly accurately using the Bohr model of the atom, which conceptualizes the electron as "orbiting" the proton in analogy to the Earth's orbit of the Sun. However, the electromagnetic force attracts electrons and protons to one another, while planets and celestial objects are attracted to each other by gravity. Because of the discretization of angular momentum postulated in early quantum mechanics by Bohr, the electron in the Bohr model can only occupy certain allowed distances from the proton, and therefore only certain allowed energies.[21]

A more accurate description of the hydrogen atom comes from a purely quantum mechanical treatment that uses the Schrödinger equation, Dirac equation or even the Feynman path integral formulation to calculate the probability density of the electron around the proton.[22] The most complicated treatments allow for the small effects of special relativity and vacuum polarization. In the quantum mechanical treatment, the electron in a ground state hydrogen atom has no angular momentum at all—an illustration of how the "planetary orbit" conception of electron motion differs from reality.

Elemental molecular forms

There exist two different spin isomers of hydrogen diatomic molecules that differ by the relative spin of their nuclei.[23] In the orthohydrogen form, the spins of the two protons are parallel and form a triplet state with a molecular spin quantum number of 1 (1⁄2+1⁄2); in the parahydrogen form the spins are antiparallel and form a singlet with a molecular spin quantum number of 0 (1⁄2–1⁄2). At standard temperature and pressure, hydrogen gas contains about 25% of the para form and 75% of the ortho form, also known as the "normal form".[24] The equilibrium ratio of orthohydrogen to parahydrogen depends on temperature, but because the ortho form is an excited state and has a higher energy than the para form, it is unstable and cannot be purified. At very low temperatures, the equilibrium state is composed almost exclusively of the para form. The liquid and gas phase thermal properties of pure parahydrogen differ significantly from those of the normal form because of differences in rotational heat capacities, as discussed more fully in spin isomers of hydrogen.[25] The ortho/para distinction also occurs in other hydrogen-containing molecules or functional groups, such as water and methylene, but is of little significance for their thermal properties.[26]

The uncatalyzed interconversion between para and ortho H2 increases with increasing temperature; thus rapidly condensed H2 contains large quantities of the high-energy ortho form that converts to the para form very slowly.[27] The ortho/para ratio in condensed H2 is an important consideration in the preparation and storage of liquid hydrogen: the conversion from ortho to para is exothermic and produces enough heat to evaporate some of the hydrogen liquid, leading to loss of liquefied material. Catalysts for the ortho-para interconversion, such as ferric oxide, activated carbon, platinized asbestos, rare earth metals, uranium compounds, chromic oxide, or some nickel[28] compounds, are used during hydrogen cooling.[29]

Phases

Compounds

Covalent and organic compounds

While H2 is not very reactive under standard conditions, it does form compounds with most elements. Hydrogen can form compounds with elements that are more electronegative, such as halogens (e.g., F, Cl, Br, I), or oxygen; in these compounds hydrogen takes on a partial positive charge.[30] When bonded to fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen, hydrogen can participate in a form of medium-strength noncovalent bonding called hydrogen bonding, which is critical to the stability of many biological molecules.[31][32] Hydrogen also forms compounds with less electronegative elements, such as the metals and metalloids, in which it takes on a partial negative charge. These compounds are often known as hydrides.[33]Hydrogen forms a vast array of compounds with carbon called the hydrocarbons, and an even vaster array with heteroatoms that, because of their general association with living things, are called organic compounds.[34] The study of their properties is known as organic chemistry[35] and their study in the context of living organisms is known as biochemistry.[36] By some definitions, "organic" compounds are only required to contain carbon. However, most of them also contain hydrogen, and because it is the carbon-hydrogen bond which gives this class of compounds most of its particular chemical characteristics, carbon-hydrogen bonds are required in some definitions of the word "organic" in chemistry.[34] Millions of hydrocarbons are known, and they are usually formed by complicated synthetic pathways, which seldom involve elementary hydrogen.

Hydrides

Compounds of hydrogen are often called hydrides, a term that is used fairly loosely. The term "hydride" suggests that the H atom has acquired a negative or anionic character, denoted H−, and is used when hydrogen forms a compound with a more electropositive element. The existence of the hydride anion, suggested by Gilbert N. Lewis in 1916 for group I and II salt-like hydrides, was demonstrated by Moers in 1920 by the electrolysis of molten lithium hydride (LiH), producing a stoichiometry quantity of hydrogen at the anode.[37] For hydrides other than group I and II metals, the term is quite misleading, considering the low electronegativity of hydrogen. An exception in group II hydrides is BeH2, which is polymeric. In lithium aluminium hydride, the AlH−

4 anion carries hydridic centers firmly attached to the Al(III).

Although hydrides can be formed with almost all main-group elements, the number and combination of possible compounds varies widely; for example, there are over 100 binary borane hydrides known, but only one binary aluminium hydride.[38] Binary indium hydride has not yet been identified, although larger complexes exist.[39]

In inorganic chemistry, hydrides can also serve as bridging ligands that link two metal centers in a coordination complex. This function is particularly common in group 13 elements, especially in boranes (boron hydrides) and aluminium complexes, as well as in clustered carboranes.[40]

Protons and acids

Oxidation of hydrogen removes its electron and gives H+, which contains no electrons and a nucleus which is usually composed of one proton. That is why H+ is often called a proton. This species is central to discussion of acids. Under the Bronsted-Lowry theory, acids are proton donors, while bases are proton acceptors.A bare proton, H+, cannot exist in solution or in ionic crystals, because of its unstoppable attraction to other atoms or molecules with electrons. Except at the high temperatures associated with plasmas, such protons cannot be removed from the electron clouds of atoms and molecules, and will remain attached to them. However, the term 'proton' is sometimes used loosely and metaphorically to refer to positively charged or cationic hydrogen attached to other species in this fashion, and as such is denoted "H+" without any implication that any single protons exist freely as a species.To avoid the implication of the naked "solvated proton" in solution, acidic aqueous solutions are sometimes considered to contain a less unlikely fictitious species, termed the "hydronium ion" (H

3O+). However, even in this case, such solvated hydrogen cations are more realistically conceived as being organized into clusters that form species closer to H

9O+

4.[41] Other oxonium ions are found when water is in acidic solution with other solvents.[42]

Although exotic on Earth, one of the most common ions in the universe is the H+

3 ion, known as protonated molecular hydrogen or the trihydrogen cation.[43]

Isotopes

Hydrogen has three naturally occurring isotopes, denoted 1H, 2H and 3H. Other, highly unstable nuclei (4H to 7H) have been synthesized in the laboratory but not observed in nature.[44][45]

- 1H is the most common hydrogen isotope with an abundance of more than 99.98%. Because the nucleus of this isotope consists of only a single proton, it is given the descriptive but rarely used formal name protium.[46]

- 2H, the other stable hydrogen isotope, is known as deuterium and contains one proton and one neutron in its nucleus. Essentially all deuterium in the universe is thought to have been produced at the time of the Big Bang, and has endured since that time. Deuterium is not radioactive, and does not represent a significant toxicity hazard. Water enriched in molecules that include deuterium instead of normal hydrogen is called heavy water. Deuterium and its compounds are used as a non-radioactive label in chemical experiments and in solvents for 1H-NMR spectroscopy.[47] Heavy water is used as a neutron moderator and coolant for nuclear reactors. Deuterium is also a potential fuel for commercial nuclear fusion.[48]

- 3H is known as tritium and contains one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. It is radioactive, decaying into helium-3 through beta decay with a half-life of 12.32 years.[40] It is so radioactive that it can be used in luminous paint, making it useful in such things as watches. The glass prevents the small amount of radiation from getting out.[49] Small amounts of tritium occur naturally because of the interaction of cosmic rays with atmospheric gases; tritium has also been released during nuclear weapons tests.[50] It is used in nuclear fusion reactions,[51] as a tracer in isotope geochemistry,[52] and specialized in self-powered lighting devices.[53] Tritium has also been used in chemical and biological labeling experiments as a radiolabel.[54]

History

Discovery and use

In 1671, Robert Boyle discovered and described the reaction between iron filings and dilute acids, which results in the production of hydrogen gas.[57][58] In 1766, Henry Cavendish was the first to recognize hydrogen gas as a discrete substance, by naming the gas from a metal-acid reaction "flammable air". He speculated that "flammable air" was in fact identical to the hypothetical substance called "phlogiston"[59][60] and further finding in 1781 that the gas produces water when burned. He is usually given credit for its discovery as an element.[6][7] In 1783, Antoine Lavoisier gave the element the name hydrogen (from the Greek ὑδρο- hydro meaning "water" and -γενής genes meaning "creator")[8] when he and Laplace reproduced Cavendish's finding that water is produced when hydrogen is burned.[7]Lavoisier produced hydrogen for his experiments on mass conservation by reacting a flux of steam with metallic iron through an incandescent iron tube heated in a fire. Anaerobic oxidation of iron by the protons of water at high temperature can be schematically represented by the set of following reactions:

- Fe + H2O → FeO + H2

- 2 Fe + 3 H2O → Fe2O3 + 3 H2

- 3 Fe + 4 H2O → Fe3O4 + 4 H2

Hydrogen was liquefied for the first time by James Dewar in 1898 by using regenerative cooling and his invention, the vacuum flask.[7] He produced solid hydrogen the next year.[7] Deuterium was discovered in December 1931 by Harold Urey, and tritium was prepared in 1934 by Ernest Rutherford, Mark Oliphant, and Paul Harteck.[6] Heavy water, which consists of deuterium in the place of regular hydrogen, was discovered by Urey's group in 1932.[7] François Isaac de Rivaz built the first de Rivaz engine, an internal combustion engine powered by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen in 1806. Edward Daniel Clarke invented the hydrogen gas blowpipe in 1819. The Döbereiner's lamp and limelight were invented in 1823.[7]

The first hydrogen-filled balloon was invented by Jacques Charles in 1783.[7] Hydrogen provided the lift for the first reliable form of air-travel following the 1852 invention of the first hydrogen-lifted airship by Henri Giffard.[7] German count Ferdinand von Zeppelin promoted the idea of rigid airships lifted by hydrogen that later were called Zeppelins; the first of which had its maiden flight in 1900.[7] Regularly scheduled flights started in 1910 and by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, they had carried 35,000 passengers without a serious incident. Hydrogen-lifted airships were used as observation platforms and bombers during the war.

The first non-stop transatlantic crossing was made by the British airship R34 in 1919. Regular passenger service resumed in the 1920s and the discovery of helium reserves in the United States promised increased safety, but the U.S. government refused to sell the gas for this purpose. Therefore, H2 was used in the Hindenburg airship, which was destroyed in a midair fire over New Jersey on 6 May 1937.[7] The incident was broadcast live on radio and filmed. Ignition of leaking hydrogen is widely assumed to be the cause, but later investigations pointed to the ignition of the aluminized fabric coating by static electricity. But the damage to hydrogen's reputation as a lifting gas was already done.

In the same year the first hydrogen-cooled turbogenerator went into service with gaseous hydrogen as a coolant in the rotor and the stator in 1937 at Dayton, Ohio, by the Dayton Power & Light Co,[61] because of the thermal conductivity of hydrogen gas this is the most common type in its field today.

The nickel hydrogen battery was used for the first time in 1977 aboard the U.S. Navy's Navigation technology satellite-2 (NTS-2).[62] For example, the ISS,[63] Mars Odyssey[64] and the Mars Global Surveyor[65] are equipped with nickel-hydrogen batteries. In the dark part of its orbit, the Hubble Space Telescope is also powered by nickel-hydrogen batteries, which were finally replaced in May 2009,[66] more than 19 years after launch, and 13 years over their design life.[67]

Role in quantum theory

Hydrogen emission spectrum lines in the visible range. These are the four visible lines of the Balmer series

Because of its relatively simple atomic structure, consisting only of a proton and an electron, the hydrogen atom, together with the spectrum of light produced from it or absorbed by it, has been central to the development of the theory of atomic structure.[68] Furthermore, the corresponding simplicity of the hydrogen molecule and the corresponding cation H+

2 allowed fuller understanding of the nature of the chemical bond, which followed shortly after the quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom had been developed in the mid-1920s.

One of the first quantum effects to be explicitly noticed (but not understood at the time) was a Maxwell observation involving hydrogen, half a century before full quantum mechanical theory arrived. Maxwell observed that the specific heat capacity of H2 unaccountably departs from that of a diatomic gas below room temperature and begins to increasingly resemble that of a monatomic gas at cryogenic temperatures. According to quantum theory, this behavior arises from the spacing of the (quantized) rotational energy levels, which are particularly wide-spaced in H2 because of its low mass. These widely spaced levels inhibit equal partition of heat energy into rotational motion in hydrogen at low temperatures. Diatomic gases composed of heavier atoms do not have such widely spaced levels and do not exhibit the same effect.[69]

Natural occurrence

Hydrogen, as atomic H, is the most abundant chemical element in the universe, making up 75% of normal matter by mass and over 90% by number of atoms (most of the mass of the universe, however, is not in the form of chemical-element type matter, but rather is postulated to occur as yet-undetected forms of mass such as dark matter and dark energy).[70] This element is found in great abundance in stars and gas giant planets. Molecular clouds of H2 are associated with star formation. Hydrogen plays a vital role in powering stars through the proton-proton reaction and the CNO cycle nuclear fusion.[71]

Throughout the universe, hydrogen is mostly found in the atomic and plasma states whose properties are quite different from molecular hydrogen. As a plasma, hydrogen's electron and proton are not bound together, resulting in very high electrical conductivity and high emissivity (producing the light from the Sun and other stars). The charged particles are highly influenced by magnetic and electric fields. For example, in the solar wind they interact with the Earth's magnetosphere giving rise to Birkeland currents and the aurora. Hydrogen is found in the neutral atomic state in the interstellar medium. The large amount of neutral hydrogen found in the damped Lyman-alpha systems is thought to dominate the cosmological baryonic density of the Universe up to redshift z=4.[72]

Under ordinary conditions on Earth, elemental hydrogen exists as the diatomic gas, H2. However, hydrogen gas is very rare in the Earth's atmosphere (1 ppm by volume) because of its light weight, which enables it to escape from Earth's gravity more easily than heavier gases. However, hydrogen is the third most abundant element on the Earth's surface,[73] mostly in the form of chemical compounds such as hydrocarbons and water.[40] Hydrogen gas is produced by some bacteria and algae and is a natural component of flatus, as is methane, itself a hydrogen source of increasing importance.[74]

A molecular form called protonated molecular hydrogen (H+

3) is found in the interstellar medium, where it is generated by ionization of molecular hydrogen from cosmic rays. This charged ion has also been observed in the upper atmosphere of the planet Jupiter. The ion is relatively stable in the environment of outer space due to the low temperature and density. H+

3 is one of the most abundant ions in the Universe, and it plays a notable role in the chemistry of the interstellar medium.[75] Neutral triatomic hydrogen H3 can only exist in an excited form and is unstable.[76] By contrast, the positive hydrogen molecular ion (H+

2) is a rare molecule in the universe.

Production

H2 is produced in chemistry and biology laboratories, often as a by-product of other reactions; in industry for the hydrogenation of unsaturated substrates; and in nature as a means of expelling reducing equivalents in biochemical reactions.Metal-acid

In the laboratory, H2 is usually prepared by the reaction of dilute non-oxidizing acids on some reactive metals such as zinc with Kipp's apparatus.

- Zn + 2 H+ → Zn2+ + H

2

2 upon treatment with bases:

- 2 Al + 6 H

2O + 2 OH− → 2 Al(OH)−

4 + 3 H

2

- 2 H

2O(l) → 2 H

2(g) + O

2(g)

Steam reforming

Hydrogen can be prepared in several different ways, but economically the most important processes involve removal of hydrogen from hydrocarbons. Commercial bulk hydrogen is usually produced by the steam reforming of natural gas.[79] At high temperatures (1000–1400 K, 700–1100 °C or 1300–2000 °F), steam (water vapor) reacts with methane to yield carbon monoxide and H2.

- CH

4 + H

2O → CO + 3 H

2

2 is the most marketable product and Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) purification systems work better at higher pressures. The product mixture is known as "synthesis gas" because it is often used directly for the production of methanol and related compounds. Hydrocarbons other than methane can be used to produce synthesis gas with varying product ratios. One of the many complications to this highly optimized technology is the formation of coke or carbon:

- CH

4 → C + 2 H

2

2O. Additional hydrogen can be recovered from the steam by use of carbon monoxide through the water gas shift reaction, especially with an iron oxide catalyst. This reaction is also a common industrial source of carbon dioxide:[79]

- CO + H

2O → CO

2 + H

2

2 production include partial oxidation of hydrocarbons:[80]

- 2 CH

4 + O

2 → 2 CO + 4 H

2

- C + H

2O → CO + H

2

Thermochemical

There are more than 200 thermochemical cycles which can be used for water splitting, around a dozen of these cycles such as the iron oxide cycle, cerium(IV) oxide–cerium(III) oxide cycle, zinc zinc-oxide cycle, sulfur-iodine cycle, copper-chlorine cycle and hybrid sulfur cycle are under research and in testing phase to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water and heat without using electricity.[83] A number of laboratories (including in France, Germany, Greece, Japan, and the USA) are developing thermochemical methods to produce hydrogen from solar energy and water.[84]Anaerobic corrosion

Under anaerobic conditions, iron and steel alloys are slowly oxidized by the protons of water concomitantly reduced in molecular hydrogen (H2). The anaerobic corrosion of iron leads first to the formation of ferrous hydroxide (green rust) and can be described by the following reaction:

- Fe + 2 H

2O → Fe(OH)

2 + H

2

2 ) can be oxidized by the protons of water to form magnetite and molecular hydrogen. This process is described by the Schikorr reaction:

- 3 Fe(OH)

2 → Fe

3O

4 + 2 H

2O + H

2 - ferrous hydroxide → magnetite + water + hydrogen

3O

4) is thermodynamically more stable than the ferrous hydroxide (Fe(OH)

2 ).

This process occurs during the anaerobic corrosion of iron and steel in oxygen-free groundwater and in reducing soils below the water table.

Geological occurrence: the serpentinization reaction

In the absence of atmospheric oxygen (O2), in deep geological conditions prevailing far away from Earth atmosphere, hydrogen (H

2) is produced during the process of serpentinization by the anaerobic oxidation by the water protons (H+) of the ferrous (Fe2+) silicate present in the crystal lattice of the fayalite (Fe

2SiO

4, the olivine iron-endmember). The corresponding reaction leading to the formation of magnetite (Fe

3O

4), quartz (SiO

2) and hydrogen (H

2) is the following:

- 3Fe

2SiO

4 + 2 H

2O → 2 Fe

3O

4 + 3 SiO

2 + 3 H

2 - fayalite + water → magnetite + quartz + hydrogen

Formation in transformers

From all the fault gases formed in power transformers, hydrogen is the most common and is generated under most fault conditions; thus, formation of hydrogen is an early indication of serious problems in the transformer's life cycle.[85]Xylose

In 2014 a low-temperature 50 °C (122 °F), atmospheric-pressure enzyme-driven process to convert xylose into hydrogen with nearly 100% of the theoretical yield was announced. The process employs 13 enzymes, including a novel polyphosphate xylulokinase (XK).[86][87]Applications

Consumption in processes

Large quantities of H2 are needed in the petroleum and chemical industries. The largest application of H

2 is for the processing ("upgrading") of fossil fuels, and in the production of ammonia. The key consumers of H

2 in the petrochemical plant include hydrodealkylation, hydrodesulfurization, and hydrocracking. H

2 has several other important uses. H

2 is used as a hydrogenating agent, particularly in increasing the level of saturation of unsaturated fats and oils (found in items such as margarine), and in the production of methanol. It is similarly the source of hydrogen in the manufacture of hydrochloric acid. H

2 is also used as a reducing agent of metallic ores.[88]

Hydrogen is highly soluble in many rare earth and transition metals[89] and is soluble in both nanocrystalline and amorphous metals.[90] Hydrogen solubility in metals is influenced by local distortions or impurities in the crystal lattice.[91] These properties may be useful when hydrogen is purified by passage through hot palladium disks, but the gas's high solubility is a metallurgical problem, contributing to the embrittlement of many metals,[12] complicating the design of pipelines and storage tanks.[13]

Apart from its use as a reactant, H

2 has wide applications in physics and engineering. It is used as a shielding gas in welding methods such as atomic hydrogen welding.[92][93] H2 is used as the rotor coolant in electrical generators at power stations, because it has the highest thermal conductivity of any gas. Liquid H2 is used in cryogenic research, including superconductivity studies.[94] Because H

2 is lighter than air, having a little more than 1⁄14 of the density of air, it was once widely used as a lifting gas in balloons and airships.[95]

In more recent applications, hydrogen is used pure or mixed with nitrogen (sometimes called forming gas) as a tracer gas for minute leak detection. Applications can be found in the automotive, chemical, power generation, aerospace, and telecommunications industries.[96] Hydrogen is an authorized food additive (E 949) that allows food package leak testing among other anti-oxidizing properties.[97]

Hydrogen's rarer isotopes also each have specific applications. Deuterium (hydrogen-2) is used in nuclear fission applications as a moderator to slow neutrons, and in nuclear fusion reactions.[7] Deuterium compounds have applications in chemistry and biology in studies of reaction isotope effects.[98] Tritium (hydrogen-3), produced in nuclear reactors, is used in the production of hydrogen bombs,[99] as an isotopic label in the biosciences,[54] and as a radiation source in luminous paints.[100]

The triple point temperature of equilibrium hydrogen is a defining fixed point on the ITS-90 temperature scale at 13.8033 kelvins.[101]

Coolant

Hydrogen is commonly used in power stations as a coolant in generators due to a number of favorable properties that are a direct result of its light diatomic molecules. These include low density, low viscosity, and the highest specific heat and thermal conductivity of all gases.Energy carrier

Hydrogen is not an energy resource,[102] except in the hypothetical context of commercial nuclear fusion power plants using deuterium or tritium, a technology presently far from development.[103] The Sun's energy comes from nuclear fusion of hydrogen, but this process is difficult to achieve controllably on Earth.[104] Elemental hydrogen from solar, biological, or electrical sources require more energy to make it than is obtained by burning it, so in these cases hydrogen functions as an energy carrier, like a battery. Hydrogen may be obtained from fossil sources (such as methane), but these sources are unsustainable.[102]The energy density per unit volume of both liquid hydrogen and compressed hydrogen gas at any practicable pressure is significantly less than that of traditional fuel sources, although the energy density per unit fuel mass is higher.[102] Nevertheless, elemental hydrogen has been widely discussed in the context of energy, as a possible future carrier of energy on an economy-wide scale.[105] For example, CO

2 sequestration followed by carbon capture and storage could be conducted at the point of H

2 production from fossil fuels.[106] Hydrogen used in transportation would burn relatively cleanly, with some NOx emissions,[107] but without carbon emissions.[106] However, the infrastructure costs associated with full conversion to a hydrogen economy would be substantial.[108]

Semiconductor industry

Hydrogen is employed to saturate broken ("dangling") bonds of amorphous silicon and amorphous carbon that helps stabilizing material properties.[109] It is also a potential electron donor in various oxide materials, including ZnO,[110][111] SnO2, CdO, MgO,[112] ZrO2, HfO2, La2O3, Y2O3, TiO2, SrTiO3, LaAlO3, SiO2, Al2O3, ZrSiO4, HfSiO4, and SrZrO3.[113]Biological reactions

H2 is a product of some types of anaerobic metabolism and is produced by several microorganisms, usually via reactions catalyzed by iron- or nickel-containing enzymes called hydrogenases. These enzymes catalyze the reversible redox reaction between H2 and its component two protons and two electrons. Creation of hydrogen gas occurs in the transfer of reducing equivalents produced during pyruvate fermentation to water.[114]Water splitting, in which water is decomposed into its component protons, electrons, and oxygen, occurs in the light reactions in all photosynthetic organisms. Some such organisms, including the alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and cyanobacteria, have evolved a second step in the dark reactions in which protons and electrons are reduced to form H2 gas by specialized hydrogenases in the chloroplast.[115] Efforts have been undertaken to genetically modify cyanobacterial hydrogenases to efficiently synthesize H2 gas even in the presence of oxygen.[116] Efforts have also been undertaken with genetically modified alga in a bioreactor.[117]

Safety and precautions

Hydrogen poses a number of hazards to human safety, from potential detonations and fires when mixed with air to being an asphyxiant in its pure, oxygen-free form.[118] In addition, liquid hydrogen is a cryogen and presents dangers (such as frostbite) associated with very cold liquids.[119] Hydrogen dissolves in many metals, and, in addition to leaking out, may have adverse effects on them, such as hydrogen embrittlement,[120] leading to cracks and explosions.[121] Hydrogen gas leaking into external air may spontaneously ignite. Moreover, hydrogen fire, while being extremely hot, is almost invisible, and thus can lead to accidental burns.[122]Even interpreting the hydrogen data (including safety data) is confounded by a number of phenomena. Many physical and chemical properties of hydrogen depend on the parahydrogen/orthohydrogen ratio (it often takes days or weeks at a given temperature to reach the equilibrium ratio, for which the data is usually given). Hydrogen detonation parameters, such as critical detonation pressure and temperature, strongly depend on the container geometry.[118]