n-Butyllithium, an organometallic compound. Four lithium atoms (in purple) form a tetrahedron, with four butyl groups attached to the faces (carbon is black, hydrogen is white).

Organometallic chemistry is the study of organometallic compounds, chemical compounds containing at least one chemical bond between a carbon atom of an organic molecule and a metal,

including alkaline, alkaline earth, and transition metals, and

sometimes broadened to include metalloids like boron, silicon, and tin,

as well. Aside from bonds to organyl fragments or molecules, bonds to 'inorganic' carbon, like carbon monoxide (metal carbonyls), cyanide, or carbide, are generally considered to be organometallic as well. Some related compounds such as transition metal hydrides and metal phosphine complexes

are often included in discussions of organometallic compounds, though

strictly speaking, they are not necessarily organometallic. The related

but distinct term "metalorganic compound"

refers to metal-containing compounds lacking direct metal-carbon bonds

but which contain organic ligands. Metal β-diketonates, alkoxides,

dialkylamides, and metal phosphine complexes are representative members

of this class. The field of organometallic chemistry combines aspects

of traditional inorganic and organic chemistry.

Organometallic compounds are widely used both stoichiometrically

in research and industrial chemical reactions, as well as in the role of

catalysts to increase the rates of such reactions (e.g., as in uses of homogeneous catalysis), where target molecules include polymers, pharmaceuticals, and many other types of practical products.

Organometallic compounds

Organometallic

compounds are distinguished by the prefix "organo-" e.g.

organopalladium compounds. Examples of such organometallic compounds

include all Gilman reagents, which contain lithium and copper. Tetracarbonyl nickel, and ferrocene are examples of organometallic compounds containing transition metals. Other examples include organomagnesium compounds like iodo(methyl)magnesium MeMgI, dimethylmagnesium (Me2Mg), and all Grignard reagents; organolithium compounds such as n-butyllithium (n-BuLi), organozinc compounds such as diethylzinc (Et2Zn) and chloro(ethoxycarbonylmethyl)zinc (ClZnCH2C(=O)OEt); and organocopper compounds such as lithium dimethylcuprate (Li+[CuMe2]−).

In addition to the traditional metals, lanthanides, actinides, and semimetals, elements such as boron, silicon, arsenic, and selenium are considered to form organometallic compounds, e.g. organoborane compounds such as triethylborane (Et3B).

- Representative Organometallic Compounds

- Ferrocene is an archetypal organoiron complex. It is an air-stable, sublimable compound.

- Cobaltocene is a structural analogue of ferrocene, but is highly reactive toward air.

- Tris(triphenylphosphine)rhodium carbonyl hydride is used in the commercial production of many aldehyde-based fragrances.

- Zeise's salt is an example of a transition metal alkene complex.

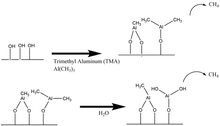

- Trimethylaluminium is an organometallic compound with a bridging methyl group. It is used in the industrial production of some alcohols

- Dimethylzinc has a linear coordination. It is a volatile pyrophoric liquid that is used in the preparation of semiconducting films.

Coordination compounds with organic ligands

Many complexes feature coordination bonds between a metal and organic ligands. The organic ligands often bind the metal through a heteroatom

such as oxygen or nitrogen, in which case such compounds are considered

coordination compounds. However, if any of the ligands form a direct

M-C bond, then complex is usually considered to be organometallic, e.g.,

[(C6H6)Ru(H2O)3]2+. Furthermore, many lipophilic compounds such as metal acetylacetonates and metal alkoxides are called "metalorganics."

A naturally occurring transition metal alkyl complex is methylcobalamin (a form of Vitamin B12), with a cobalt-methyl bond. This subset of complexes is often discussed within the subfield of bioorganometallic chemistry. Illustrative of the many functions of the B12-dependent enzymes, the MTR enzyme catalyzes the transfer of a methyl group from a nitrogen on N5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate to the sulfur of homocysteine to produce methionine.

The status of compounds in which the canonical anion has a

delocalized structure in which the negative charge is shared with an

atom more electronegative than carbon, as in enolates,

may vary with the nature of the anionic moiety, the metal ion, and

possibly the medium; in the absence of direct structural evidence for a

carbon–metal bond, such compounds are not considered to be

organometallic. For instance, lithium enolates often contain only Li-O

bonds and are not organometallic, while zinc enolates (Reformatsky

reagents) contain both Zn-O and Zn-C bonds, and are organometallic in

nature.

Structure and properties

The metal-carbon bond in organometallic compounds is generally highly covalent.

For highly electropositive elements, such as lithium and sodium, the

carbon ligand exhibits carbanionic character, but free carbon-based

anions are extremely rare, an example being cyanide.

Concepts and techniques

As in other areas of chemistry, electron counting is useful for organizing organometallic chemistry. The 18-electron rule is helpful in predicting the stabilities of metal carbonyls

and related compounds. Most organometallic compounds do not however

follow the 18e rule. Chemical bonding and reactivity in organometallic

compounds is often discussed from the perspective of the isolobal principle.

As well as X-ray diffraction, NMR and infrared spectroscopy

are common techniques used to determine structure. The dynamic

properties of organometallic compounds is often probed with

variable-temperature NMR and chemical kinetics.

Organometallic compounds undergo several important reactions:

- oxidative addition and reductive elimination

- transmetalation

- carbometalation

- hydrometalation

- electron transfer

- β-hydride elimination

- organometallic substitution reaction

- carbon-hydrogen bond activation

- cyclometalation

- migratory insertion

- nucleophilic abstraction

History

Early developments in organometallic chemistry include Louis Claude Cadet's synthesis of methyl arsenic compounds related to cacodyl, William Christopher Zeise's platinum-ethylene complex, Edward Frankland's discovery of diethyl- and dimethylzinc, Ludwig Mond's discovery of Ni(CO)4, and Victor Grignard's organomagnesium compounds. (Though not always acknowledged as an organometallic compound, Prussian blue, a mixed-valence iron-cyanide complex, was first prepared in 1706 by paint maker Johann Jacob Diesbach as the first coordination polymer and synthetic material containing a metal-carbon bond.) The abundant and diverse products from coal and petroleum led to Ziegler-Natta, Fischer-Tropsch, hydroformylation catalysis which employ CO, H2, and alkenes as feedstocks and ligands.

Recognition of organometallic chemistry as a distinct subfield culminated in the Nobel Prizes to Ernst Fischer and Geoffrey Wilkinson for work on metallocenes. In 2005, Yves Chauvin, Robert H. Grubbs and Richard R. Schrock shared the Nobel Prize for metal-catalyzed olefin metathesis.

Organometallic chemistry timeline

- 1760 Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt investigates inks based on cobalt salts and isolates cacodyl from cobalt mineral containing arsenic

- 1827 William Christopher Zeise produces Zeise's salt; the first platinum / olefin complex

- 1848 Edward Frankland discovers diethylzinc

- 1863 Charles Friedel and James Crafts prepare organochlorosilanes

- 1890 Ludwig Mond discovers nickel carbonyl

- 1899 Introduction of Grignard reaction

- 1899 John Ulric Nef discovers alkynylation using sodium acetylides.

- 1900 Paul Sabatier works on hydrogenation organic compounds with metal catalysts. Hydrogenation of fats kicks off advances in food industry, see margarine

- 1909 Paul Ehrlich introduces Salvarsan for the treatment of syphilis, an early arsenic based organometallic compound

- 1912 Nobel Prize Victor Grignard and Paul Sabatier

- 1930 Henry Gilman works on lithium cuprates, see Gilman reagent

- 1951 Walter Hieber was awarded the Alfred Stock prize for his work with metal carbonyl chemistry.

- 1951 Ferrocene is discovered

- 1956 Dorothy Crawfoot Hodgkin determines the structure of vitamin B12, the first biomolecule found to contain a metal-carbon bond, see bioorganometallic chemistry

- 1963 Nobel prize for Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta on Ziegler-Natta catalyst

- 1965 Discovery of cyclobutadieneiron tricarbonyl

- 1968 Heck reaction

- 1973 Nobel prize Geoffrey Wilkinson and Ernst Otto Fischer on sandwich compounds

- 1981 Nobel prize Roald Hoffmann and Kenichi Fukui for creation of the Woodward-Hoffman Rules

- 2001 Nobel prize W. S. Knowles, R. Noyori and Karl Barry Sharpless for asymmetric hydrogenation

- 2005 Nobel prize Yves Chauvin, Robert Grubbs, and Richard Schrock on metal-catalyzed alkene metathesis

- 2010 Nobel prize Richard F. Heck, Ei-ichi Negishi, Akira Suzuki for palladium catalyzed cross coupling reactions

Scope

Subspecialty areas of organometallic chemistry include:

- Period 2 elements: organolithium chemistry, organoberyllium chemistry, organoborane chemistry,

- Period 3 elements: organomagnesium chemistry, organoaluminum chemistry, organosilicon chemistry

- Period 4 elements: organotitanium chemistry, organochromium chemistry, organomanganese chemistry organoiron chemistry, organocobalt chemistry organonickel chemistry, organocopper chemistry, organozinc chemistry, organogallium chemistry, organogermanium chemistry

- Period 5 elements: organoruthenium chemistry, organopalladium chemistry, organosilver chemistry, organocadmium chemistry, organoindium chemistry, organotin chemistry

- Period 6 elements: organolanthanide chemistry, organoosmium chemistry, organoiridium chemistry, organoplatinum chemistry, organogold chemistry, organomercury chemistry, organothallium chemistry, organolead chemistry

- Period 7 elements: organouranium chemistry

Industrial applications

Organometallic compounds find wide use in commercial reactions, both as homogeneous catalysis and as stoichiometric reagents For instance, organolithium, organomagnesium, and organoaluminium compounds,

examples of which are highly basic and highly reducing, are useful

stoichiometrically, but also catalyze many polymerization reactions.

Almost all processes involving carbon monoxide rely on catalysts, notable examples being described as carbonylations. The production of acetic acid from methanol and carbon monoxide is catalyzed via metal carbonyl complexes in the Monsanto process and Cativa process. Most synthetic aldehydes are produced via hydroformylation. The bulk of the synthetic alcohols, at least those larger than ethanol, are produced by hydrogenation of hydroformylation-derived aldehydes. Similarly, the Wacker process is used in the oxidation of ethylene to acetaldehyde.

Almost all industrial processes involving alkene-derived polymers rely on organometallic catalysts. The world's polyethylene and polypropylene are produced via both heterogeneously via Ziegler-Natta catalysis and homogeneously, e.g., via constrained geometry catalysts.

Most processes involving hydrogen rely on metal-based catalysts.

Whereas bulk hydrogenations, e.g. margarine production, rely on

heterogeneous catalysts, For the production of fine chemicals, such hydrogenations rely on soluble organometallic complexes or involve organometallic intermediates. Organometallic complexes allow these hydrogenations to be effected asymmetrically.

A constrained geometry organotitanium complex is a precatalyst for olefin polymerization.

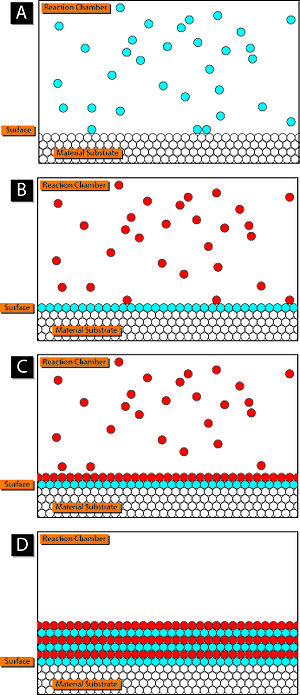

Many semiconductors are produced from trimethylgallium, trimethylindium, trimethylaluminium, and trimethylantimony. These volatile compounds are decomposed along with ammonia, arsine, phosphine and related hydrides on a heated substrate via metalorganic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) process in the production of light-emitting diodes (LEDs).

Organometallic reactions

The synthesis of many organic molecules are facilitated by organometallic complexes. Sigma-bond metathesis is a synthetic method for forming new carbon-carbon sigma bonds. Sigma-bond metathesis is typically used with early transition-metal complexes that are in their highest oxidation state. Using transition-metals that are in their highest oxidation state prevents other reactions from occurring, such as oxidative addition. In addition to sigma-bond metathesis, olefin metathesis is used to synthesize various carbon-carbon pi bonds. Neither sigma-bond metathesis or olefin metathesis change the oxidation state of the metal. Many other methods are used to form new carbon-carbon bonds, including beta-hydride elimination and insertion reactions.

Catalysis

Organometallic complexes are commonly used in catalysis. Major industrial processes include hydrogenation, hydrosilylation, hydrocyanation, olefin metathesis, alkene polymerization, alkene oligomerization, hydrocarboxylation, methanol carbonylation, and hydroformylation. Organometallic intermediates are also invoked in many heterogeneous catalysis processes, analogues to those listed above. Additionally, organometallic intermediates are assumed for Fischer-Tropsch process.

Organometallic complexes are commonly used in small-scale fine chemical synthesis as well, especially in cross-coupling reactions that form carbon-carbon bonds, e.g. Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, Buchwald-Hartwig amination for producing aryl amines from aryl halides, and Sonogashira coupling, etc.

Environmental concerns

Natural

and contaminant organometallic compounds are found in the environment.

Some that are remnants of human use, such as organolead and

organomercury compounds, are toxicity hazards. Tetraethyllead was prepared for use as a gasoline additive but has fallen into disuse because of lead's toxicity. Its replacements are other organometallic compounds, such as ferrocene and methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT). The organoarsenic compound

roxarsone is a controversial animal feed additive. In 2006,

approximately one million kilograms of it were produced in the U.S

alone.