The term diabetes

includes several different metabolic disorders that all, if left

untreated, result in abnormally high concentration of a sugar called glucose in the blood. Diabetes mellitus type 1 results when the pancreas no longer produces significant amounts of the hormone insulin, usually owing to the autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. Diabetes mellitus type 2, in contrast, is now thought to result from autoimmune attacks on the pancreas and/or insulin resistance.

The pancreas of a person with type 2 diabetes may be producing normal

or even abnormally large amounts of insulin. Other forms of diabetes

mellitus, such as the various forms of maturity onset diabetes of the young,

may represent some combination of insufficient insulin production and

insulin resistance. Some degree of insulin resistance may also be

present in a person with type 1 diabetes.

The main goal of diabetes management is, as far as possible, to restore carbohydrate metabolism to a normal state. To achieve this goal, individuals with an absolute deficiency of insulin require insulin replacement therapy, which is given through injections or an insulin pump. Insulin resistance, in contrast, can be corrected by dietary modifications and exercise. Other goals of diabetes management are to prevent or treat the many complications that can result from the disease itself and from its treatment.

The main goal of diabetes management is, as far as possible, to restore carbohydrate metabolism to a normal state. To achieve this goal, individuals with an absolute deficiency of insulin require insulin replacement therapy, which is given through injections or an insulin pump. Insulin resistance, in contrast, can be corrected by dietary modifications and exercise. Other goals of diabetes management are to prevent or treat the many complications that can result from the disease itself and from its treatment.

Overview

Goals

The treatment goals are related to effective control of blood glucose, blood pressure and lipids, to minimize the risk of long-term consequences associated with diabetes. They are suggested in clinical practice guidelines released by various national and international diabetes agencies.

The targets are:

- HbA1c of less than 6% or 7.0% if they are achievable without significant hypoglycemia

- Preprandial blood glucose: 3.9 to 7.2 mmol/L (70 to 130 mg/dl)

- 2-hour postprandial blood glucose: <10 dl="" mg="" mmol="" nbsp="" span="">

Goals should be individualized based on:

- Duration of diabetes

- Age/life expectancy

- Comorbidity

- Known cardiovascular disease or advanced microvascular disease

- Hypoglycemia awareness

In older patients, clinical practice guidelines by the American Geriatrics Society

states "for frail older adults, persons with life expectancy of less

than 5 years, and others in whom the risks of intensive glycemic control

appear to outweigh the benefits, a less stringent target such as HbA1c of 8% is appropriate".

Issues

The

primary issue requiring management is that of the glucose cycle. In

this, glucose in the bloodstream is made available to cells in the body;

a process dependent upon the twin cycles of glucose entering the

bloodstream, and insulin allowing appropriate uptake into the body

cells. Both aspects can require management. Another issue that ties

along with the glucose cycle is getting a balanced amount of the glucose

to the major organs so they are not affected negatively.

Complexities

Daily glucose and insulin cycle

The main complexities stem from the nature of the feedback loop of the glucose cycle, which is sought to be regulated:

- The glucose cycle is a system which is affected by two factors: entry of glucose into the bloodstream and also blood levels of insulin to control its transport out of the bloodstream

- As a system, it is sensitive to diet and exercise

- It is affected by the need for user anticipation due to the complicating effects of time delays between any activity and the respective impact on the glucose system

- Management is highly intrusive, and compliance is an issue, since it relies upon user lifestyle change and often upon regular sampling and measuring of blood glucose levels, multiple times a day in many cases

- It changes as people grow and develop

- It is highly individual

As diabetes is a prime risk factor for cardiovascular disease,

controlling other risk factors which may give rise to secondary

conditions, as well as the diabetes itself, is one of the facets of

diabetes management. Checking cholesterol, LDL, HDL and triglyceride levels may indicate hyperlipoproteinemia, which may warrant treatment with hypolipidemic drugs. Checking the blood pressure and keeping it within strict limits (using diet and antihypertensive treatment) protects against the retinal, renal and cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Regular follow-up by a podiatrist or other foot health specialists is encouraged to prevent the development of diabetic foot. Annual eye exams are suggested to monitor for progression of diabetic retinopathy.

Early advancements

Late

in the 19th century, sugar in the urine (glycosuria) was associated

with diabetes. Various doctors studied the connection. Frederick Madison Allen studied diabetes in 1909–12, then published a large volume, Studies Concerning Glycosuria and Diabetes, (Boston, 1913). He invented a fasting treatment for diabetes called the Allen treatment for diabetes. His diet was an early attempt at managing diabetes.

Blood sugar level

Blood sugar level is measured by means of a glucose meter,

with the result either in mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter in the US) or

mmol/L (millimoles per litre in Canada and Eastern Europe) of blood.

The average normal person has an average fasting glucose level of

4.5 mmol/L (81 mg/dL), with a lows of down to 2.5 and up to 5.4 mmol/L

(65 to 98 mg/dL).

Optimal management of diabetes involves patients measuring and recording their own blood glucose

levels. By keeping a diary of their own blood glucose measurements and

noting the effect of food and exercise, patients can modify their

lifestyle to better control their diabetes. For patients on insulin,

patient involvement is important in achieving effective dosing and

timing.

Hypo and hyperglycemia

Levels

which are significantly above or below this range are problematic and

can in some cases be dangerous. A level of <3 .8="" a="" as="" described="" dl="" i="" is="" mg="" mmol="" nbsp="" usually="">hypoglycemic attack

(low blood sugar).

Most diabetics know when they are going to "go hypo" and usually are

able to eat some food or drink something sweet to raise levels. A

patient who is hyperglycemic (high glucose) can also become

temporarily hypoglycemic, under certain conditions (e.g. not eating

regularly, or after strenuous exercise, followed by fatigue). Intensive

efforts to achieve blood sugar levels close to normal have been shown

to triple the risk of the most severe form of hypoglycemia, in which the

patient requires assistance from by-standers in order to treat the

episode.

In the United States, there were annually 48,500 hospitalizations for

diabetic hypoglycemia and 13,100 for diabetic hypoglycemia resulting in

coma in the period 1989 to 1991, before intensive blood sugar control

was as widely recommended as today.

One study found that hospital admissions for diabetic hypoglycemia

increased by 50% from 1990–1993 to 1997–2000, as strict blood sugar

control efforts became more common.

Among intensively controlled type 1 diabetics, 55% of episodes of

severe hypoglycemia occur during sleep, and 6% of all deaths in

diabetics under the age of 40 are from nocturnal hypoglycemia in the

so-called 'dead-in-bed syndrome,' while National Institute of Health

statistics show that 2% to 4% of all deaths in diabetics are from

hypoglycemia. In children and adolescents following intensive blood sugar control, 21% of hypoglycemic episodes occurred without explanation.

In addition to the deaths caused by diabetic hypoglycemia, periods of

severe low blood sugar can also cause permanent brain damage.

Although diabetic nerve disease is usually associated with

hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia as well can initiate or worsen neuropathy in

diabetics intensively struggling to reduce their hyperglycemia.

Levels greater than 13–15 mmol/L (230–270 mg/dL) are considered

high, and should be monitored closely to ensure that they reduce rather

than continue to remain high. The patient is advised to seek urgent

medical attention as soon as possible if blood sugar levels continue to

rise after 2–3 tests. High blood sugar levels are known as hyperglycemia,

which is not as easy to detect as hypoglycemia and usually happens over

a period of days rather than hours or minutes. If left untreated, this

can result in diabetic coma and death.

A blood glucose test strip for an older style (i.e., optical color sensing) monitoring system

Prolonged and elevated levels of glucose in the blood, which is left

unchecked and untreated, will, over time, result in serious diabetic

complications in those susceptible and sometimes even death. There is

currently no way of testing for susceptibility to complications.

Diabetics are therefore recommended to check their blood sugar levels

either daily or every few days. There is also diabetes management software

available from blood testing manufacturers which can display results

and trends over time. Type 1 diabetics normally check more often, due to

insulin therapy.

A history of blood sugar level results is especially useful for

the diabetic to present to their doctor or physician in the monitoring

and control of the disease. Failure to maintain a strict regimen of

testing can accelerate symptoms of the condition, and it is therefore

imperative that any diabetic patient strictly monitor their glucose

levels regularly.

Glycemic control

Glycemic control is a medical term referring to the typical levels of blood sugar (glucose) in a person with diabetes mellitus.

Much evidence suggests that many of the long-term complications of

diabetes, especially the microvascular complications, result from many

years of hyperglycemia

(elevated levels of glucose in the blood). Good glycemic control, in

the sense of a "target" for treatment, has become an important goal of

diabetes care, although recent research suggests that the complications

of diabetes may be caused by genetic factors or, in type 1 diabetics, by the continuing effects of the autoimmune disease which first caused the pancreas to lose its insulin-producing ability.

Because blood sugar levels fluctuate throughout the day and

glucose records are imperfect indicators of these changes, the

percentage of hemoglobin which is glycosylated

is used as a proxy measure of long-term glycemic control in research

trials and clinical care of people with diabetes. This test, the hemoglobin A1c or glycosylated hemoglobin

reflects average glucoses over the preceding 2–3 months. In nondiabetic

persons with normal glucose metabolism the glycosylated hemoglobin is

usually 4–6% by the most common methods (normal ranges may vary by

method).

"Perfect glycemic control" would mean that glucose levels were

always normal (70–130 mg/dl, or 3.9–7.2 mmol/L) and indistinguishable

from a person without diabetes. In reality, because of the imperfections

of treatment measures, even "good glycemic control" describes blood

glucose levels that average somewhat higher than normal much of the

time. In addition, one survey of type 2 diabetics found that they rated

the harm to their quality of life from intensive interventions to

control their blood sugar to be just as severe as the harm resulting

from intermediate levels of diabetic complications.

In the 1990s the American Diabetes Association

conducted a publicity campaign to persuade patients and physicians to

strive for average glucose and hemoglobin A1c values below 200 mg/dl

(11 mmol/l) and 8%. Currently many patients and physicians attempt to do

better than that.

As of 2015 the guidelines called for an HbA1c of

around 7% or a fasting glucose of less than 7.2 mmol/L (130 mg/dL);

however these goals may be changed after professional clinical

consultation, taking into account particular risks of hypoglycemia and life expectancy.

Despite guidelines recommending that intensive blood sugar control be

based on balancing immediate harms and long-term benefits, many people –

for example people with a life expectancy of less than nine years – who

will not benefit are over-treated and do not experience clinically meaningful benefits.

Poor glycemic control refers to persistently elevated blood

glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels, which may range from

200–500 mg/dl (11–28 mmol/L) and 9–15% or higher over months and years

before severe complications occur. Meta-analysis of large studies done

on the effects of tight

vs. conventional, or more relaxed, glycemic control in type 2 diabetics

have failed to demonstrate a difference in all-cause cardiovascular

death, non-fatal stroke, or limb amputation, but decreased the risk of

nonfatal heart attack by 15%. Additionally, tight glucose control

decreased the risk of progression of retinopathy and nephropathy, and

decreased the incidence peripheral neuropathy, but increased the risk of

hypoglycemia 2.4 times.

Monitoring

A modern portable blood glucose meter (OneTouch Ultra), displaying a reading of 5.4 mmol/L (98 mg/dL).

Relying on their own perceptions of symptoms of hyperglycemia or

hypoglycemia is usually unsatisfactory as mild to moderate hyperglycemia

causes no obvious symptoms in nearly all patients. Other considerations

include the fact that, while food takes several hours to be digested

and absorbed, insulin administration can have glucose lowering effects

for as little as 2 hours or 24 hours or more (depending on the nature of

the insulin preparation used and individual patient reaction). In

addition, the onset and duration of the effects of oral hypoglycemic

agents vary from type to type and from patient to patient.

Personal (home) glucose monitoring

Control and outcomes of both types 1 and 2 diabetes may be improved by patients using home glucose meters to regularly measure their glucose levels.

Glucose monitoring is both expensive (largely due to the cost of the

consumable test strips) and requires significant commitment on the part

of the patient. Lifestyle adjustments are generally made by the patients

themselves following training by a clinician.

Regular blood testing, especially in type 1 diabetics, is helpful

to keep adequate control of glucose levels and to reduce the chance of

long term side effects of the disease. There are many (at least 20+) different types of blood monitoring devices

available on the market today; not every meter suits all patients and

it is a specific matter of choice for the patient, in consultation with a

physician or other experienced professional, to find a meter that they

personally find comfortable to use. The principle of the devices is

virtually the same: a small blood sample is collected and measured. In

one type of meter, the electrochemical, a small blood sample is produced

by the patient using a lancet (a sterile pointed needle). The blood

droplet is usually collected at the bottom of a test strip, while the

other end is inserted in the glucose meter. This test strip contains

various chemicals so that when the blood is applied, a small electrical

charge is created between two contacts. This charge will vary depending

on the glucose levels within the blood. In older glucose meters, the

drop of blood is placed on top of a strip. A chemical reaction occurs

and the strip changes color. The meter then measures the color of the

strip optically.

Self-testing is clearly important in type I diabetes where the

use of insulin therapy risks episodes of hypoglycemia and home-testing

allows for adjustment of dosage on each administration. Its benefit in type 2 diabetes has been more controversial, but recent studies have resulted in guidance that self-monitoring does not improve blood glucose or quality of life.

Benefits of control and reduced hospital admission have been reported.

However, patients on oral medication who do not self-adjust their drug

dosage will miss many of the benefits of self-testing, and so it is

questionable in this group. This is particularly so for patients taking

monotherapy with metformin who are not at risk of hypoglycaemia. Regular 6 monthly laboratory testing of HbA1c

(glycated haemoglobin) provides some assurance of long-term effective

control and allows the adjustment of the patient's routine medication

dosages in such cases. High frequency of self-testing in type 2 diabetes

has not been shown to be associated with improved control.

The argument is made, though, that type 2 patients with poor long term

control despite home blood glucose monitoring, either have not had this

integrated into their overall management, or are long overdue for

tighter control by a switch from oral medication to injected insulin.

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM)

CGM technology has been rapidly developing to give people living with

diabetes an idea about the speed and direction of their glucose changes.

While it still requires calibration from SMBG and is not indicated for

use in correction boluses, the accuracy of these monitors is increasing

with every innovation. The Libre Blood Sugar Diet Program utilizes the

CGM and Libre Sensor and by collecting all the data through a smart

phone and smart watch experts analyze this data 24/7 in Real Time. The

results are that certain foods can be identified as causing one's blood

sugar levels to rise and other foods as safe foods- that do not make a

person's blood sugar levels to rise. Each individual absorbs sugar

differently and this is why testing is a necessity.

HbA1c test

A useful test that has usually been done in a laboratory is the measurement of blood HbA1c levels. This is the ratio of glycated hemoglobin

in relation to the total hemoglobin. Persistent raised plasma glucose

levels cause the proportion of these molecules to go up. This is a test

that measures the average amount of diabetic control over a period

originally thought to be about 3 months (the average red blood cell

lifetime), but more recently

thought to be more strongly weighted to the most recent 2 to 4 weeks.

In the non-diabetic, the HbA1c level ranges from 4.0–6.0%; patients with

diabetes mellitus who manage to keep their HbA1c level below 6.5% are

considered to have good glycemic control. The HbA1c test is not

appropriate if there has been changes to diet or treatment within

shorter time periods than 6 weeks or there is disturbance of red cell

aging (e.g. recent bleeding or hemolytic anemia) or a hemoglobinopathy (e.g. sickle cell disease). In such cases the alternative Fructosamine test is used to indicate average control in the preceding 2 to 3 weeks.

Continuous glucose monitoring

The first CGM device made available to consumers was the GlucoWatch

biographer in 1999. This product is no longer sold. It was a

retrospective device rather than live. Several live monitoring devices

have subsequently been manufactured which provide ongoing monitoring of

glucose levels on an automated basis during the day.

Lifestyle modification

The British National Health Service

launched a programme targeting 100,000 people at risk of diabetes to

lose weight and take more exercise in 2016. In 2019 it was announced

that the programme was successful. The 17,000 people who attended most

of the healthy living sessions had, collectively lost nearly 60,000 kg,

and the programme was to be doubled in size.

Diet

Because high blood sugar caused by poorly controlled diabetes can

lead to a plethora of immediate and long-term complications, it is

critical to maintain blood sugars as close to normal as possible, and a

diet that produces more controllable glycemic variability is an

important factor in producing normal blood sugars.

People with type 1 diabetes who use insulin can eat whatever they want, preferably a healthy diet

with some carbohydrate content; in the long term it is helpful to eat a

consistent amount of carbohydrate to make blood sugar management

easier.

There is a lack of evidence of the usefulness of low-carbohydrate dieting for people with type 1 diabetes. Although for certain individuals it may be feasible to follow a low-carbohydrate regime combined with carefully-managed insulin dosing, this is hard to maintain and there are concerns about potential adverse health effects caused by the diet. In general people with type 1 diabetes are advised to follow an individualized eating plan rather than a pre-decided one.

Medications

Currently, one goal for diabetics is to avoid or minimize chronic diabetic complications, as well as to avoid acute problems of hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia. Adequate control of diabetes leads to lower risk of complications associated with unmonitored diabetes including kidney failure (requiring dialysis or transplant), blindness, heart disease and limb amputation. The most prevalent form of medication is hypoglycemic treatment through either oral hypoglycemics and/or insulin

therapy. There is emerging evidence that full-blown diabetes mellitus

type 2 can be evaded in those with only mildly impaired glucose

tolerance.

Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus require direct injection

of insulin as their bodies cannot produce enough (or even any) insulin.

As of 2010, there is no other clinically available form of insulin

administration other than injection for patients with type 1: injection

can be done by insulin pump, by jet injector, or any of several forms of hypodermic needle.

Non-injective methods of insulin administration have been unattainable

as the insulin protein breaks down in the digestive tract. There are

several insulin application mechanisms under experimental development as

of 2004, including a capsule that passes to the liver and delivers

insulin into the bloodstream. There have also been proposed vaccines for type I using glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), but these are currently not being tested by the pharmaceutical companies that have sublicensed the patents to them.

For type 2 diabetics, diabetic management consists of a combination of diet, exercise, and weight loss,

in any achievable combination depending on the patient. Obesity is very

common in type 2 diabetes and contributes greatly to insulin

resistance. Weight reduction and exercise improve tissue sensitivity to

insulin and allow its proper use by target tissues.

Patients who have poor diabetic control after lifestyle modifications

are typically placed on oral hypoglycemics. Some Type 2 diabetics

eventually fail to respond to these and must proceed to insulin therapy.

A study conducted in 2008 found that increasingly complex and costly

diabetes treatments are being applied to an increasing population with

type 2 diabetes. Data from 1994 to 2007 was analyzed and it was found

that the mean number of diabetes medications per treated patient

increased from 1.14 in 1994 to 1.63 in 2007.

Patient education and compliance with treatment is very important

in managing the disease. Improper use of medications and insulin can be

very dangerous causing hypo- or hyper-glycemic episodes.

Insulin

Insulin pen used to administer insulin

For type 1 diabetics, there will always be a need for insulin

injections throughout their life, as the pancreatic beta cells of a type

1 diabetic are not capable of producing sufficient insulin. However,

both type 1 and type 2 diabetics can see dramatic improvements in blood

sugars through modifying their diet, and some type 2 diabetics can fully

control the disease by dietary modification.

Insulin therapy

requires close monitoring and a great deal of patient education, as

improper administration is quite dangerous. For example, when food

intake is reduced, less insulin is required. A previously satisfactory

dosing may be too much if less food is consumed causing a hypoglycemic

reaction if not intelligently adjusted. Exercise decreases insulin

requirements as exercise increases glucose uptake by body cells whose

glucose uptake is controlled by insulin, and vice versa. In addition,

there are several types of insulin with varying times of onset and

duration of action.

Several companies are currently working to develop a

non-invasive version of insulin, so that injections can be avoided.

Mannkind has developed an inhalable version, while companies like Novo Nordisk,

Oramed and BioLingus have efforts undergoing for an oral product.

Also oral combination products of insulin and a GLP-1 agonist are being

developed.

Insulin therapy creates risk because of the inability to

continuously know a person's blood glucose level and adjust insulin

infusion appropriately. New advances in technology have overcome much

of this problem. Small, portable insulin infusion pumps are available

from several manufacturers. They allow a continuous infusion of small

amounts of insulin to be delivered through the skin around the clock,

plus the ability to give bolus doses when a person eats or has elevated

blood glucose levels. This is very similar to how the pancreas works,

but these pumps lack a continuous "feed-back" mechanism. Thus, the user

is still at risk of giving too much or too little insulin unless blood

glucose measurements are made.

A further danger of insulin treatment is that while diabetic

microangiopathy is usually explained as the result of hyperglycemia,

studies in rats indicate that the higher than normal level of insulin

diabetics inject to control their hyperglycemia may itself promote small

blood vessel disease.

While there is no clear evidence that controlling hyperglycemia

reduces diabetic macrovascular and cardiovascular disease, there are

indications that intensive efforts to normalize blood glucose levels may

worsen cardiovascular and cause diabetic mortality.

Driving

Paramedics

in Southern California attend a diabetic man who lost effective control

of his vehicle due to low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and drove it over

the curb and into the water main and backflow valve in front of this

industrial building. He was not injured, but required emergency

intravenous glucose.

Studies conducted in the United States and Europe

showed that drivers with type 1 diabetes had twice as many collisions

as their non-diabetic spouses, demonstrating the increased risk of

driving collisions in the type 1 diabetes population. Diabetes can

compromise driving safety in several ways. First, long-term

complications of diabetes can interfere with the safe operation of a

vehicle. For example, diabetic retinopathy (loss of peripheral vision or visual acuity), or peripheral neuropathy

(loss of feeling in the feet) can impair a driver’s ability to read

street signs, control the speed of the vehicle, apply appropriate

pressure to the brakes, etc.

Second, hypoglycemia can affect a person’s thinking process, coordination, and state of consciousness. This disruption in brain functioning is called neuroglycopenia. Studies have demonstrated that the effects of neuroglycopenia impair driving ability.

A study involving people with type 1 diabetes found that individuals

reporting two or more hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps differ

physiologically and behaviorally from their counterparts who report no

such mishaps.

For example, during hypoglycemia, drivers who had two or more mishaps

reported fewer warning symptoms, their driving was more impaired, and

their body released less epinephrine (a hormone that helps raise BG).

Additionally, individuals with a history of hypoglycemia-related driving

mishaps appear to use sugar at a faster rate and are relatively slower at processing information.

These findings indicate that although anyone with type 1 diabetes may

be at some risk of experiencing disruptive hypoglycemia while driving,

there is a subgroup of type 1 drivers who are more vulnerable to such

events.

Given the above research findings, it is recommended that drivers

with type 1 diabetes with a history of driving mishaps should never

drive when their BG is less than 70 mg/dl (3.9 mmol/l). Instead, these

drivers are advised to treat hypoglycemia and delay driving until their

BG is above 90 mg/dl (5 mmol/l).

Such drivers should also learn as much as possible about what causes

their hypoglycemia, and use this information to avoid future

hypoglycemia while driving.

Studies funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have

demonstrated that face-to-face training programs designed to help

individuals with type 1 diabetes better anticipate, detect, and prevent

extreme BG can reduce the occurrence of future hypoglycemia-related

driving mishaps. An internet-version of this training has also been shown to have significant beneficial results.

Additional NIH funded research to develop internet interventions

specifically to help improve driving safety in drivers with type 1

diabetes is currently underway.

Exenatide

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a treatment called Exenatide, based on the saliva of a Gila monster, to control blood sugar in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Other regimens

Artificial Intelligence researcher Dr. Cynthia Marling, of the Ohio University Russ College of Engineering and Technology, in collaboration with the Appalachian Rural Health Institute Diabetes Center, is developing a case based reasoning

system to aid in diabetes management. The goal of the project is to

provide automated intelligent decision support to diabetes patients and

their professional care providers by interpreting the ever-increasing

quantities of data provided by current diabetes management technology

and translating it into better care without time consuming manual effort

on the part of an endocrinologist or diabetologist. This type of Artificial Intelligence-based treatment shows some promise with initial testing of a prototype system producing best practice

treatment advice which anaylizing physicians deemed to have some degree

of benefit over 70% of the time and advice of neutral benefit another

nearly 25% of the time.

Use of a "Diabetes Coach" is becoming an increasingly popular way to manage diabetes. A Diabetes Coach is usually a Certified diabetes educator

(CDE) who is trained to help people in all aspects of caring for their

diabetes. The CDE can advise the patient on diet, medications, proper

use of insulin injections and pumps, exercise, and other ways to manage

diabetes while living a healthy and active lifestyle. CDEs can be found

locally or by contacting a company which provides personalized diabetes

care using CDEs. Diabetes Coaches can speak to a patient on a

pay-per-call basis or via a monthly plan.

Dental care

High blood glucose in diabetic people is a risk factor for developing gum and tooth problems, especially in post-puberty and aging individuals. Diabetic patients have greater chances of developing oral health problems such as tooth decay, salivary gland dysfunction, fungal infections, inflammatory skin disease, periodontal disease or taste impairment and thrush of the mouth.

The oral problems in persons suffering from diabetes can be prevented

with a good control of the blood sugar levels, regular check-ups and a

very good oral hygiene. By maintaining a good oral status, diabetic persons prevent losing their teeth as a result of various periodontal conditions.

Diabetic persons must increase their awareness about oral

infections as they have a double impact on health. Firstly, people with

diabetes are more likely to develop periodontal disease, which causes

increased blood sugar levels, often leading to diabetes complications.

Severe periodontal disease can increase blood sugar, contributing to

increased periods of time when the body functions with a high blood

sugar. This puts diabetics at increased risk for diabetic complications.

The first symptoms of gum and tooth infection in diabetic persons are decreased salivary flow and burning mouth or tongue.

Also, patients may experience signs like dry mouth, which increases the

incidence of decay. Poorly controlled diabetes usually leads to gum

recession, since plaque creates more harmful proteins in the gums.

Tooth decay and cavities are some of the first oral problems that

individuals with diabetes are at risk for. Increased blood sugar levels

translate into greater sugars and acids that attack the teeth and lead

to gum diseases. Gingivitis can also occur as a result of increased blood sugar levels along with an inappropriate oral hygiene. Periodontitis

is an oral disease caused by untreated gingivitis and which destroys

the soft tissue and bone that support the teeth. This disease may cause

the gums to pull away from the teeth which may eventually loosen and

fall out. Diabetic people tend to experience more severe periodontitis

because diabetes lowers the ability to resist infection

and also slows healing. At the same time, an oral infection such as

periodontitis can make diabetes more difficult to control because it

causes the blood sugar levels to rise.

To prevent further diabetic complications as well as serious oral

problems, diabetic persons must keep their blood sugar levels under

control and have a proper oral hygiene. A study in the Journal of

Periodontology found that poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients are

more likely to develop periodontal disease than well-controlled

diabetics are.

At the same time, diabetic patients are recommended to have regular

checkups with a dental care provider at least once in three to four

months. Diabetics who receive good dental care and have good insulin

control typically have a better chance at avoiding gum disease to help

prevent tooth loss.

Dental care is therefore even more important for diabetic

patients than for healthy individuals. Maintaining the teeth and gum

healthy is done by taking some preventing measures such as regular

appointments at a dentist and a very good oral hygiene. Also, oral

health problems can be avoided by closely monitoring the blood sugar

levels. Patients who keep better under control their blood sugar levels

and diabetes are less likely to develop oral health problems when

compared to diabetic patients who control their disease moderately or

poorly.

Poor oral hygiene is a great factor to take under consideration

when it comes to oral problems and even more in people with diabetes.

Diabetic people are advised to brush their teeth at least twice a day,

and if possible, after all meals and snacks. However, brushing in the morning and at night is mandatory as well as flossing and using an anti-bacterial mouthwash. Individuals who suffer from diabetes are recommended to use toothpaste that contains fluoride

as this has proved to be the most efficient in fighting oral infections

and tooth decay. Flossing must be done at least once a day, as well

because it is helpful in preventing oral problems by removing the plaque

between the teeth, which is not removed when brushing.

Diabetic patients must get professional dental cleanings every six months. In cases when dental surgery is needed, it is necessary to take some special precautions such as adjusting diabetes medication or taking antibiotics to prevent infection. Looking for early signs of gum disease (redness, swelling, bleeding gums) and informing the dentist about them is also helpful in preventing further complications. Quitting smoking is recommended to avoid serious diabetes complications and oral diseases.

Diabetic persons are advised to make morning appointments to the

dental care provider as during this time of the day the blood sugar

levels tend to be better kept under control. Not least, individuals who

suffer from diabetes must make sure both their physician and dental care

provider are informed and aware of their condition, medical history and

periodontal status.

Medication nonadherence

Because

many patients with diabetes have two or more comorbidities, they often

require multiple medications. The prevalence of medication nonadherence

is high among patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, and

nonadherence is associated with public health issues and higher health

care costs. One reason for nonadherence is the cost of medications.

Being able to detect cost-related nonadherence is important for health

care professionals, because this can lead to strategies to assist

patients with problems paying for their medications. Some of these

strategies are use of generic drugs or therapeutic alternatives,

substituting a prescription drug with an over-the-counter medication,

and pill-splitting. Interventions to improve adherence can achieve

reductions in diabetes morbidity and mortality, as well as significant

cost savings to the health care system.

Smartphone apps have been found to improve self-management and health

outcomes in people with diabetes through functions such as specific

reminder alarms,

while working with mental health professionals has also been found to

help people with diabetes develop the skills to manage their medications

and challenges of self-management effectively.

Psychological mechanisms and adherence

As

self-management of diabetes typically involves lifestyle modifications,

adherence may pose a significant self-management burden on many

individuals.

For example, individuals with diabetes may find themselves faced with

the need to self-monitor their blood glucose levels, adhere to healthier

diets and maintain exercise regimens regularly in order to maintain

metabolic control and reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular

problems. Barriers to adherence have been associated with key

psychological mechanisms: knowledge of self-management, beliefs about

the efficacy of treatment and self-efficacy/perceived control.

Such mechanisms are inter-related, as one's thoughts (e.g. one's

perception of diabetes, or one's appraisal of how helpful

self-management is) is likely to relate to one's emotions (e.g.

motivation to change), which in turn, affects one's self-efficacy (one's

confidence in their ability to engage in a behaviour to achieve a

desired outcome).

As diabetes management is affected by an individual's emotional

and cognitive state, there has been evidence suggesting the

self-management of diabetes is negatively affected by diabetes-related

distress and depression.

There is growing evidence that there is higher levels of clinical

depression in patients with diabetes compared to the non-diabetic

population. Depression in individuals with diabetes has been found to be associated with poorer self-management of symptoms. This suggests that it may be important to target mood in treatment.

To this end, treatment programs such as the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy - Adherence and Depression program (CBT-AD)

have been developed to target the psychological mechanisms underpinning

adherence. By working on increasing motivation and challenging

maladaptive illness perceptions, programs such as CBT-AD aim to enhance

self-efficacy and improve diabetes-related distress and one's overall

quality of life.

Research

Type 1 diabetes

Diabetes type 1 is caused by the destruction of enough beta cells to produce symptoms; these cells, which are found in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas, produce and secrete insulin, the single hormone responsible for allowing glucose to enter from the blood into cells (in addition to the hormone amylin, another hormone required for glucose homeostasis). Hence, the phrase "curing diabetes type 1" means "causing a maintenance or restoration of the endogenous

ability of the body to produce insulin in response to the level of

blood glucose" and cooperative operation with counterregulatory

hormones.

This section deals only with approaches for curing the underlying

condition of diabetes type 1, by enabling the body to endogenously, in vivo,

produce insulin in response to the level of blood glucose. It does not

cover other approaches, such as, for instance, closed-loop integrated

glucometer/insulin pump products, which could potentially increase the

quality-of-life for some who have diabetes type 1, and may by some be

termed "artificial pancreas".

Encapsulation approach

The Bio-artificial pancreas: a cross section of bio-engineered tissue with encapsulated islet cells delivering endocrine hormones in response to glucose

A biological approach to the artificial pancreas is to implant bioengineered tissue containing islet cells, which would secrete the amounts of insulin, amylin and glucagon needed in response to sensed glucose.

When islet cells have been transplanted via the Edmonton protocol, insulin production (and glycemic control) was restored, but at the expense of continued immunosuppression drugs. Encapsulation

of the islet cells in a protective coating has been developed to block

the immune response to transplanted cells, which relieves the burden of

immunosuppression and benefits the longevity of the transplant.

Stem cells

Research is being done at several locations in which islet cells are developed from stem cells.

Stem cell research has also been suggested as a potential avenue

for a cure since it may permit regrowth of Islet cells which are

genetically part of the treated individual, thus perhaps eliminating the

need for immuno-suppressants.[48] This new method autologous

nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation was developed

by a research team composed by Brazilian and American scientists (Dr.

Julio Voltarelli, Dr. Carlos Eduardo Couri, Dr Richard Burt, and

colleagues) and it was the first study to use stem cell therapy in human

diabetes mellitus This was initially tested in mice and in 2007 there

was the first publication of stem cell therapy to treat this form of

diabetes.

Until 2009, there was 23 patients included and followed for a mean

period of 29.8 months (ranging from 7 to 58 months). In the trial,

severe immunosuppression with high doses of cyclophosphamide and

anti-thymocyte globulin is used with the aim of "turning off" the

immunologic system", and then autologous hematopoietic stem cells are

reinfused to regenerate a new one. In summary it is a kind of

"immunologic reset" that blocks the autoimmune attack against residual

pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Until December 2009, 12 patients

remained continuously insulin-free for periods ranging from 14 to 52

months and 8 patients became transiently insulin-free for periods

ranging from 6 to 47 months. Of these last 8 patients, 2 became

insulin-free again after the use of sitagliptin, a DPP-4 inhibitor

approved only to treat type 2 diabetic patients and this is also the

first study to document the use and complete insulin-independendce in

humans with type 1 diabetes with this medication. In parallel with

insulin suspension, indirect measures of endogenous insulin secretion

revealed that it significantly increased in the whole group of patients,

regardless the need of daily exogenous insulin use.

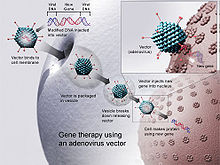

Gene therapy

Gene therapy: Designing a viral vector to deliberately infect cells with DNA to carry on the viral production of insulin in response to the blood sugar level.

Technology for gene therapy

is advancing rapidly such that there are multiple pathways possible to

support endocrine function, with potential to practically cure diabetes.

- Gene therapy can be used to manufacture insulin directly: an oral medication, consisting of viral vectors containing the insulin sequence, is digested and delivers its genes to the upper intestines. Those intestinal cells will then behave like any viral infected cell, and will reproduce the insulin protein. The virus can be controlled to infect only the cells which respond to the presence of glucose, such that insulin is produced only in the presence of high glucose levels. Due to the limited numbers of vectors delivered, very few intestinal cells would actually be impacted and would die off naturally in a few days. Therefore, by varying the amount of oral medication used, the amount of insulin created by gene therapy can be increased or decreased as needed. As the insulin-producing intestinal cells die off, they are boosted by additional oral medications.

- Gene therapy might eventually be used to cure the cause of beta cell destruction, thereby curing the new diabetes patient before the beta cell destruction is complete and irreversible.

- Gene therapy can be used to turn duodenum cells and duodenum adult stem cells into beta cells which produce insulin and amylin naturally. By delivering beta cell DNA to the intestine cells in the duodenum, a few intestine cells will turn into beta cells, and subsequently adult stem cells will develop into beta cells. This makes the supply of beta cells in the duodenum self replenishing, and the beta cells will produce insulin in proportional response to carbohydrates consumed.

Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is usually first treated by increasing physical activity, and eliminating saturated fat and reducing sugar and carbohydrate intake with a goal of losing weight.

These can restore insulin sensitivity even when the weight loss is

modest, for example around 5 kg (10 to 15 lb), most especially when it

is in abdominal fat deposits. Diets that are very low in saturated fats

have been claimed to reverse insulin resistance.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is an effective intervention for

improving adherence to medication, depression and glycaemic control,

with enduring and clinically meaningful benefits for diabetes

self-management and glycaemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes and

comorbid depression.

Testosterone replacement therapy may improve glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in diabetic hypogonadal men. The mechanisms by which testosterone decreases insulin resistance is under study.

Moreover, testosterone may have a protective effect on pancreatic beta

cells, which is possibly exerted by androgen-receptor-mediated

mechanisms and influence of inflammatory cytokines.

Recently it has been suggested that a type of gastric bypass surgery

may normalize blood glucose levels in 80–100% of severely obese

patients with diabetes. The precise causal mechanisms are being

intensively researched; its results may not simply be attributable to

weight loss, as the improvement in blood sugars seems to precede any

change in body mass. This approach may become a treatment for some

people with type 2 diabetes, but has not yet been studied in prospective

clinical trials. This surgery may have the additional benefit of reducing the death rate from all causes by up to 40% in severely obese people. A small number of normal to moderately obese patients with type 2 diabetes have successfully undergone similar operations.

MODY

is a rare genetic form of diabetes, often mistaken for Type 1 or Type

2. The medical management is variable and depends on each individual

case.