The cardinal virtues are four virtues of mind and character in classical philosophy. They are prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. They form a virtue theory of ethics. The term cardinal comes from the Latin cardo (hinge); these four virtues are called "cardinal" because all other virtues fall under them and hinge upon them.

These virtues derive initially from Plato in Republic Book IV, 426-435. Aristotle expounded them systematically in the Nicomachean Ethics. They were also recognized by the Stoics and Cicero expanded on them. In the Christian tradition, they are also listed in the Deuterocanonical books in Wisdom of Solomon 8:7 and 4 Maccabees 1:18–19, and the Doctors Ambrose, Augustine, and Aquinas expounded their supernatural counterparts, the three theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity.

Four cardinal virtues

- Prudence (φρόνησις, phrónēsis; Latin: prudentia; also wisdom, sophia, sapientia), the ability to discern the appropriate course of action to be taken in a given situation at the appropriate time, with consideration of potential consequences; cautiousness.

- Justice (δικαιοσύνη, dikaiosýnē; Latin: iustitia): also considered as fairness; the Greek word also having the meaning righteousness.

- Courage (ἀνδρεία, andreía; Latin: fortitudo): forbearance, strength, endurance, fortitude (patience and perseverance), dedication and the ability to confront fear, uncertainty, and intimidation (bravery, boldness, valor, daring). Notably, ἀνδρεία, being closely related to ἀνήρ ("adult male"), could also be translated "manliness". Some other definitions of courage are "Andrea, virtus, spirit, heart, mettle, thumos, tenacity, gameness, resolution, bravery, boldness, valor, daring, hardihood, assertiveness, frame, gravitas, determination".

- Temperance (σωφροσύνη, sōphrosýnē; Latin: temperantia): also known as restraint, the practice of self-control, abstention, discretion, and moderation tempering the appetition. Plato considered sōphrosynē, which may also be translated as sound-mindedness, to be the most important virtue. σωφροσύνη was often used in reference to drinking and "knowing the right amount" to avoid belligerence.

Gallery, depiction of the cardinal virtues in 9th-century Europe

An early European representation of the cardinal virtues from 845 AD is found in the Vivian Bible, Paris.

-

The four virtues (in the corners) face a scene with King David (center), along with men who served David and who wrote psalms.

-

Fortitudo or Courage, from the Vivian Bible, Bibliothèque nationale, Latin 1, folio 215v.

-

Prydentia or Prudentia (Prudence), from the Vivian Bible.

-

Iustitia or Justice, from the Vivian Bible.

-

Temperantia or Temperance, from the Vivian Bible.

Antiquity

The four cardinal virtues appeared as a group (sometimes included in larger lists) long before they were given this title.

Hellenistic philosophy

Plato associated the four cardinal virtues with the social classes of the ideal city described in The Republic, and with the faculties of humanity. Plato narrates a discussion of the character of a good city where the following is agreed upon:

Clearly, then, it will be wise, brave, temperate [literally: healthy-minded], and just.

Temperance was most closely associated with the producing classes, the farmers and craftsmen, to moderate their animal appetites. Fortitude was assigned to the warrior class, to strengthen their fighting spirit. Prudence was assigned to the rulers, to guide their reason. Justice stood above these three to properly regulate the relations among them.

Plato sometimes lists holiness (hosiotes, eusebeia, aidos) amongst the cardinal virtues. He especially associates holiness with justice, but leaves their precise relationship unexplained.

In Aristotle's Rhetoric, we read:

The forms of Virtue are justice, courage, temperance, magnificence, magnanimity, liberality, gentleness, prudence, wisdom.

— Rhetoric 1366b1

These are expounded fully in the Nicomachean Ethics III.6-V.2.

Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher, also recognized the four cardinal virtues as prudence, temperance, courage, and justice. In his writings, he states:

In these words Moses intends to sketch out the particular virtues. And they also are four in number, prudence, temperance, courage, and justice.

— Philo, Philo's Works, Allegorical Interpretation 1.XIX

These virtues, according to Philo, serve as guiding principles for a virtuous and fulfilling life.

Roman philosophy

The Roman philosopher and statesman Cicero (106-43 BC), like Plato, limits the list to four virtues:

Virtue may be defined as a habit of mind (animi) in harmony with reason and the order of nature. It has four parts: wisdom (prudentiam), justice, courage, temperance.

— De Inventione, II, LIII

Cicero discusses these further in De Officiis (I, V, and following).

Seneca writes in Consolatio ad Helviam Matrem about justice (iustitia from Ancient Greek δικαιοσύνη), self-control (continentia from Ancient Greek σωφροσύνη), practical wisdom (prudentia from Ancient Greek φρόνησις) and devotion (pietas) instead of courage (fortitudo from Ancient Greek ἀνδρεία).

The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius discusses these in Book V:12 of Meditations and views them as the "goods" that a person should identify in one's own mind, as opposed to "wealth or things which conduce to luxury or prestige".

Suggestions of the Stoic virtues can be found in fragments in the Diogenes Laertius and Stobaeus.

The Platonist view of the four cardinal virtues is described in Definitions.

Practical wisdom or prudence (phrónēsis) is the perspicacity necessary to conduct personal business and affairs of state. It encompasses the skill to distinguish the beneficial from the detrimental, to understand the attainment of happiness, and to discern the right course of action in every situation. Its antithesis or opposite is the vice of folly.

Justice (dikaiosunê) is the harmonious alignment of one's inner self and the comprehensive integrity of the soul. It involves fostering sound discipline within each facet of our being, enabling us to live with others and extend the same regard to every individual. Additionally, justice pertains to a state's aptitude to equitably allocate resources based on individuals' deservingness, as determined by their merits. It entails refraining from undue harshness, fostering a universal perception of fairness. Furthermore, it entails embodying the qualities of a law-abiding citizen or member of society, upholding principles of social equality. Justice encompasses the formulation of laws that can be substantiated by valid justifications, leading to a society where actions align with these laws.

Moderation or temperance (sôphrosunê) is the capacity to temper the indulgence of desires and sensory pleasures within the bounds of what is customary for the individual, aligning only with experiences already familiar to the soul. It encompasses achieving a harmonious equilibrium and exercising disciplined control when it comes to overall pleasure and pain, ensuring that they remain within normal ranges. Moreover, moderation involves cultivating a harmonious relationship and a balanced rule between the soul's governing and being governed aspects. It signifies maintaining a state of natural self-reliance and exercising proper discipline as and when required by the soul. Rational consensus within the soul is essential concerning what merits admiration and what warrants disdain. This approach entails deliberate caution in one's choices, as one's selection navigates between the extremes.

Courage (andreia) can be defined as the ability to conquer fear within oneself when action is necessary. It encompasses military confidence, a deep understanding of warfare, and maintaining unwavering beliefs in the face of challenges. It involves self-discipline to overcome fear, obeying wisdom, and facing death boldly. Courage also entails maintaining sound judgment in tough situations, countering hostility, upholding virtues, remaining composed when faced with frightening (or encouraging) discussions and events, and not becoming discouraged. It reflects valuing the rule of law in our daily lives rather than diminishing its importance.

In the Bible

In the Old Testament

The cardinal virtues are listed in the deuterocanonical book Wisdom of Solomon 8:7, which reads:

She [Wisdom] teaches temperance, and prudence, and justice, and fortitude, which are such things as men can have nothing more profitable in life.

They are also found in other non-canonical scriptures like 4 Maccabees 1:18–19, which relates:

Now the kinds of wisdom are right judgment, justice, courage, and self-control. Right judgment is supreme over all of these since by means of it reason rules over the emotions.

In the New Testament

Wisdom, usually sophia, rather than Prudence (phrónēsis), is discussed extensively in all parts of the New Testament. It is a major topic of 1 Corinthians 2, where the author discusses how divine teaching and power are greater than worldly wisdom.

Justice (δικαιοσύνη, dikaiosýnē) is taught in the gospels, where most translators give it as "righteousness".

Plato's word for Fortitude (ἀνδρεία) is not present in the New Testament, but the virtues of steadfastness (ὑπομονή, hypomonē) and patient endurance (μακροθυμία, makrothymia) are praised. Paul exhorts believers to "act like men" (ἀνδρίζομαι, andrizomai, 1 Corinthians 16:13).

Temperance (σωφροσύνη, sōphrosýnē), usually translated "sobriety," is present in the New Testament, along with self-control (ἐγκράτεια, egkrateia).

In Christian tradition

Catholic moral theology drew from both the Wisdom of Solomon and the Fourth Book of Maccabees in developing its thought on the virtues. Ambrose (c. 330s – c. 397) used the expression "cardinal virtues":

And we know that there are four cardinal virtues - temperance, justice, prudence, and fortitude.

— Commentary on Luke, V, 62

Augustine of Hippo, discussing the morals of the church, described them:

For these four virtues (would that all felt their influence in their minds as they have their names in their mouths!), I should have no hesitation in defining them: that temperance is love giving itself entirely to that which is loved; fortitude is love readily bearing all things for the sake of the loved object; justice is love serving only the loved object, and therefore ruling rightly; prudence is love distinguishing with sagacity between what hinders it and what helps it.

— De moribus eccl., Chap. xv

In relation to the theological virtues

The "cardinal" virtues are not the same as the three theological virtues: Faith, Hope, and Charity (Love), named in 1 Corinthians 13.

And now these three remain: faith, hope, and love. But the greatest of these is love.

Because of this reference, a group of seven virtues is sometimes listed by adding the four cardinal virtues (prudence, temperance, fortitude, justice) and three theological virtues (faith, hope, charity). While the first four date back to Greek philosophers and were applicable to all people seeking to live moral lives, the theological virtues appear to be specific to Christians as written by Paul in the New Testament.

Efforts to relate the cardinal and theological virtues differ. Augustine sees faith as coming under justice. Beginning with a wry comment about the moral mischief of pagan deities, he writes:

They [the pagans] have made Virtue also a goddess, which, indeed, if it could be a goddess, had been preferable to many. And now, because it is not a goddess, but a gift of God, let it be obtained by prayer from Him, by whom alone it can be given, and the whole crowd of false gods vanishes. For as much as they have thought proper to distribute virtue into four divisions - prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance - and as each of these divisions has its own virtues, faith is among the parts of justice, and has the chief place with as many of us as know what that saying means, ‘The just shall live by faith.’

— City of God, IV, 20

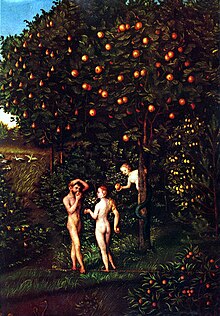

Dante Alighieri also attempts to relate the cardinal and theological virtues in his Divine Comedy, most notably in the complex allegorical scheme drawn in Purgatorio XXIX to XXXI. Depicting a procession in the Garden of Eden (which the author situates at the top of the mountain of purgatory), Dante describes a chariot drawn by a gryphon and accompanied by a vast number of figures, among which stand three women on the right side dressed in red, green, and white, and four women on the left, all dressed in purple. The chariot is generally understood to represent the holy church, with the women on right and left representing the theological and cardinal virtues respectively. The exact meaning of the allegorical women's role, behaviour, interrelation, and color-coding remains a matter of literary interpretation.

In relation to the seven deadly sins

In the High Middle Ages, some authors opposed the seven virtues (cardinal plus theological) to the seven deadly sins. However, “treatises exclusively concentrating on both septenaries are actually quite rare.” and “examples of late medieval catalogues of virtues and vices which extend or upset the double heptad can be easily multiplied.” And there are problems with this parallelism:

The opposition between the virtues and the vices to which these works allude despite the frequent inclusion of other schemes may seem unproblematic at first sight. The virtues and the vices seem to mirror each other as positive and negative moral attitudes, so that medieval authors, with their keen predilection for parallels and oppositions, could conveniently set them against each other. … Yet artistic representations such as Conrad’s trees are misleading in that they establish oppositions between the principal virtues and the capital vices which are based on mere juxtaposition. As to content, the two schemes do not match each other. The capital vices of lust and avarice, for instance, contrast with the remedial virtues of chastity and generosity, respectively, rather than with any theological or cardinal virtue; conversely, the virtues of hope and prudence are opposed to despair and foolishness rather than to any deadly sin. Medieval moral authors were well aware of the fact. Actually, the capital vices are more often contrasted with the remedial or contrary virtues in medieval moral literature than with the principal virtues, while the principal virtues are frequently accompanied by a set of mirroring vices rather than by the seven deadly sins.

Contemporary thought

Jesuit scholars Daniel J. Harrington and James F. Keenan, in their Paul and Virtue Ethics (2010), argue for seven "new virtues" to replace the classical cardinal virtues in complementing the three theological virtues, mirroring the seven earlier proposed in Bernard Lonergan's Method in Theology (1972): "be humble, be hospitable, be merciful, be faithful, reconcile, be vigilant, and be reliable".

Allegory

The Cardinal Virtues are often depicted as female allegorical figures. These were a popular subject for funerary sculpture. The attributes and names of these figures may vary according to local tradition.

Yves Decadt, a Flemish artist, has created a series of artworks titled “Falling Angels: Allegories about the 7 Sins and 7 Virtues for Falling Angels and other Curious Minds”. The series explores the topic of morality, sins, and virtues, which have dominated Western cultures for more than 2000 years. In this work, Decadt follows in the footsteps of Pieter Breughel, who made a series of sketches on the 7 sins and 7 virtues about 500 years ago. The work takes the viewer on an adventurous trip through time and across the barriers and edges of reality, mythology, religion, and culture.

The virtues in art

In many churches and artwork the Cardinal Virtues are depicted with symbolic items:

- Justice

- sword, balance and scales, a crown

- Temperance

- wheel, bridle and reins, vegetables and fish, cup, water and wine in two jugs

- Fortitude

- armor, club, with a lion, palm, tower, a yoke, a broken column

- Prudence

- book, scroll, mirror, an attacking serpent

Notable depictions include sculptures on the tomb of Francis II, Duke of Brittany and the tomb of John Hotham. They were also depicted in the garden at Edzell Castle.