A corporate haven, corporate tax haven, or multinational tax haven, is a jurisdiction that multinational corporations find attractive for establishing subsidiaries or incorporation

of regional or main company headquarters, mostly due to favourable tax

regimes (not just the headline tax rate), and/or favourable secrecy laws

(such as the avoidance of regulations or disclosure of tax schemes),

and/or favourable regulatory regimes (such as weak data-protection or

employment laws).

Modern corporate tax havens (such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Singapore) differ from traditional corporate tax havens (such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands and Jersey) in their ability to maintain OECD compliance, while using OECD–whitelisted IP-based BEPS tools and debt-based BEPS tools, which don't file public accounts, to enable the corporation to avoid taxes, not just in the corporate haven, but in all operating countries that have tax treaties with the haven.

While the "headline" corporate tax rate in corporate havens is always above zero (e.g. Netherlands at 25%, U.K. at 19%, Singapore at 17%, and Ireland at 12.5%), the "effective" tax rate (ETR) of multinational corporations, net of the BEPS tools, is closer to zero. Estimates of lost annual taxes to corporate havens range from $100 to $250 billion. To increase respectability, and access to tax treaties, some havens like Singapore and Ireland require corporates to have a "substantive presence", equating to an "employment tax" of circa 2–3% of profits shielded via the haven (if these are real jobs, the tax is mitigated).

In corporate tax haven lists, CORPNET's "Orbis connections", ranks the Netherlands, U.K., Switzerland, Ireland, and Singapore as the world's key corporate tax havens, while Zucman's "quantum of funds" ranks Ireland as the largest global corporate tax haven. In proxy tests, Ireland is the largest recipient of U.S. tax inversions (the U.K. is third, the Netherlands is fifth). Ireland's double Irish BEPS tool is credited with the largest build-up of untaxed corporate offshore cash in history. Luxembourg and Hong Kong and the Caribbean "triad" (BVI-Cayman-Bermuda), have elements of corporate tax havens, but also of traditional tax havens.

Unlike traditional tax havens, modern corporate tax havens reject they have anything to do with near-zero effective tax rates, due to their need to encourage jurisdictions to enter into bilateral tax treaties which accept the haven's BEPS tools. CORPNET show each corporate tax haven is strongly connected with specific traditional tax havens (via additional BEPS tool "backdoors" like the double Irish, the dutch sandwich, and single malt). Corporate tax havens promote themselves as "knowledge economies", and IP as a "new economy" asset, rather than a tax management tool, which is encoded into their statute books as their primary BEPS tool. This perceived respectability encourages corporates to use havens as regional headquarters (i.e. Google, Apple, and Facebook use Ireland in EMEA over Luxembourg, and Singapore in APAC over Hong Kong/Taiwan; none use the BVI–Cayman–Bermuda "triad" as a regional headquarters).

Smaller corporate havens meet the IMF–definition of an offshore financial centre, as the untaxed accounting flows from the BEPS tools, artificially distorts the economic statistics of the haven (e.g. Ireland's 2015 leprechaun economics GDP, Luxembourg's 70% GNI to GDP ratio, most of the ten major tax havens are in the top 15 GDP-per-capita proxy tax haven list). The distortion can lead to over-leverage in the haven's economy (and property bubbles), making them prone to severe credit cycles.

Modern corporate tax havens (such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Singapore) differ from traditional corporate tax havens (such as Bermuda, the Cayman Islands and Jersey) in their ability to maintain OECD compliance, while using OECD–whitelisted IP-based BEPS tools and debt-based BEPS tools, which don't file public accounts, to enable the corporation to avoid taxes, not just in the corporate haven, but in all operating countries that have tax treaties with the haven.

While the "headline" corporate tax rate in corporate havens is always above zero (e.g. Netherlands at 25%, U.K. at 19%, Singapore at 17%, and Ireland at 12.5%), the "effective" tax rate (ETR) of multinational corporations, net of the BEPS tools, is closer to zero. Estimates of lost annual taxes to corporate havens range from $100 to $250 billion. To increase respectability, and access to tax treaties, some havens like Singapore and Ireland require corporates to have a "substantive presence", equating to an "employment tax" of circa 2–3% of profits shielded via the haven (if these are real jobs, the tax is mitigated).

In corporate tax haven lists, CORPNET's "Orbis connections", ranks the Netherlands, U.K., Switzerland, Ireland, and Singapore as the world's key corporate tax havens, while Zucman's "quantum of funds" ranks Ireland as the largest global corporate tax haven. In proxy tests, Ireland is the largest recipient of U.S. tax inversions (the U.K. is third, the Netherlands is fifth). Ireland's double Irish BEPS tool is credited with the largest build-up of untaxed corporate offshore cash in history. Luxembourg and Hong Kong and the Caribbean "triad" (BVI-Cayman-Bermuda), have elements of corporate tax havens, but also of traditional tax havens.

Unlike traditional tax havens, modern corporate tax havens reject they have anything to do with near-zero effective tax rates, due to their need to encourage jurisdictions to enter into bilateral tax treaties which accept the haven's BEPS tools. CORPNET show each corporate tax haven is strongly connected with specific traditional tax havens (via additional BEPS tool "backdoors" like the double Irish, the dutch sandwich, and single malt). Corporate tax havens promote themselves as "knowledge economies", and IP as a "new economy" asset, rather than a tax management tool, which is encoded into their statute books as their primary BEPS tool. This perceived respectability encourages corporates to use havens as regional headquarters (i.e. Google, Apple, and Facebook use Ireland in EMEA over Luxembourg, and Singapore in APAC over Hong Kong/Taiwan; none use the BVI–Cayman–Bermuda "triad" as a regional headquarters).

Smaller corporate havens meet the IMF–definition of an offshore financial centre, as the untaxed accounting flows from the BEPS tools, artificially distorts the economic statistics of the haven (e.g. Ireland's 2015 leprechaun economics GDP, Luxembourg's 70% GNI to GDP ratio, most of the ten major tax havens are in the top 15 GDP-per-capita proxy tax haven list). The distortion can lead to over-leverage in the haven's economy (and property bubbles), making them prone to severe credit cycles.

Global BEPS hubs

Modern corporate tax havens, such as Ireland, Singapore, the

Netherlands and the U.K., are different from traditional "offshore" tax havens like Bermuda, the Cayman Islands or Jersey. Corporate havens offer the ability to reroute untaxed profits from higher-tax jurisdictions back to the haven; as long as these jurisdictions have bi-lateral tax treaties with the corporate haven. This makes modern corporate tax havens more potent than more traditional tax havens, who have more limited tax treaties, due to their acknowledged status.

Tools

Tax academics identify that extracting untaxed profits from higher-tax jurisdictions requires several components:

- § IP-based BEPS tools, which enable the profits to be extracted via the cross-border charge-out of group IP (known as "intergroup IP charging"); and/or

- § Debt-based BEPS tools, which enable the profits to be extracted via the cross-border charge-out artificially high interest (known as "earnings stripping"); and/or

- § TP-based BEPS tools, which enable profits to be extracted by claiming that a process performed on the product in the haven justifies a large increase in the transfer price ("TP") at which the finished product is charged-out at, by the haven, to higher-tax jurisdictions (known as contract manufacturing); and

- Bilateral tax treaties with the corporate tax haven, which accept these BEPS tools as deductible against tax in the higher-tax jurisdictions.

Once the untaxed funds are rerouted back to the corporate tax haven,

additional BEPS tools shield against paying taxes in the haven. It is

important these BEPS tools are complex and obtuse so that the higher-tax

jurisdictions do not feel the corporate haven is a traditional tax

haven (or they will suspend the bilateral tax treaties). These complex

BEPS tools often have interesting labels:

- Royalty payment BEPS tools to reroute the funds to a traditional tax haven (i.e. double Irish and single malt in Ireland or dutch sandwich in the Netherlands); or

- Capital allowance BEPS tools that allow IP assets to be written off against taxes in the haven (i.e. Apple's 2015 capital allowances for intangibles tool in leprechaun economics); or

- Lower IP-sourced income tax regimes, offering explicitly lower ETRs against charging out of cross-border group IP (i.e. the U.K. patent box, or the Irish knowledge box); or

- Beneficial treatment of interest income (from § Debt-based BEPS tools), enabling it to be treated as non-taxable (i.e. the Dutch "double dipping" interest regime); or

- Restructuring the income into a securitisation vehicle (by owning the IP, or other asset, with debt), and then "washing" the debt by "back-to-backing" with a Eurobond (i.e. Orphaned Super-QIAIF).

Execution

Building

the tools requires advanced legal and accounting skills that can create

the BEPS tools in a manner that is acceptable to major global

jurisdictions and that can be encoded into bilateral tax-treaties, and

do not look like "tax haven" type activity. Most modern corporate tax

havens therefore come from established financial centres where advanced skills are in-situ for financial structuring.

In addition to being able to create the tools, the haven needs the

respectability to use them. Large high-tax jurisdictions like Germany

do not accept IP–based BEPS tools from Bermuda but do from Ireland.

Similarly, Australia accepts limited IP–based BEPS tools from Hong Kong

but accepts the full range from Singapore.

Tax academics identify a number of elements corporate havens employ in supporting respectability:

- Non-zero headline tax

rates. While corporate tax havens have ETRs of close to zero, they all

maintain non-zero "headline" tax rates. Many of the corporate tax

havens have accounting studies to prove that their "effective" tax rates

are similar to their "headline" tax rates, but this is because they are net of the § IP-based BEPS tools which consider much of the income exempt from tax;

Make no mistake: the headline rate is not what triggers tax evasion and aggressive tax planning. That comes from schemes that facilitate [base erosion and] profit shifting [or BEPS].

— Pierre Moscovici, Financial Times, 11 March 2018 - OECD compliance and endorsement. Most corporate tax structures in modern corporate tax havens are OECD–whitelisted.

The OECD has been a long-term supporter of IP–based BEPS tools and

cross-border intergroup IP charging. All the corporate tax havens

signed the 2017 OECD MLI and marketed their compliance, however, they all opted out of the key article 12 section;

Under BEPS, new requirements for country-by-country reporting of tax and profits and other initiatives will give this further impetus, and mean even more foreign investment in Ireland.

— Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, "IP and Tax Avoidance in Ireland", 30 August 2016 - § Employment tax

strategies. Leading corporate tax havens distance themselves from

traditional tax havens by requiring corporates to establish a "presence

of substance" in their jurisdiction. This equates to an effective

"employment tax" of circa 2–3% but it gives the corporate, and the

jurisdiction, defense against accusations as being a tax haven, and is

supported in OCED MLI Article 5.

“If [the OECD] BEPS [Project] sees itself to a conclusion, it will be good for Ireland.”

— Feargal O'Rourke, CEO PwC Ireland, Irish Times, May 2015. - Data

protection laws. To maintain OECD–whitelist status, corporate tax

havens cannot use the secrecy legislation found in very traditional tax

havens. They keep the "effective" tax rates of corporations hidden with

data protection and privacy laws which prevent the public filing of

accounts and also limit the sharing of data across State departments.

Local subsidiaries of multinationals must always be required to file their accounts on public record, which is not the case at present. Ireland is not just a tax haven at present, it is also a corporate secrecy jurisdiction.

Aspects

Denial of status

Whereas traditional tax havens often market themselves as such, modern corporate tax havens deny any association with tax haven activities.

This is to ensure that other higher-tax jurisdictions, from which the

corporate's main income and profits often derive, will sign bilateral

tax-treaties with the haven, and also to avoid being black-listed.

This issue has caused debate on what constitutes a tax haven, with the OECD most focused on transparency (the key issue of traditional tax havens), but others focused on outcomes such as total effective corporate taxes paid.

It is common to see the media, and elected representatives, of a

modern corporate tax haven ask the question, "Are we a tax haven ?"

For example, when it was shown in 2014, prompted by an October 2013 Bloomberg piece, that the effective tax rate of U.S. multinationals in Ireland was 2.2% (using the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis method), it led to denials by the Irish Government and the production of studies claiming Ireland's effective tax rate was 12.5%. However, when the EU fined Apple in 2016, Ireland's largest company, €13 billion in Irish back taxes (the largest tax fine in corporate history), the EU discovered that Apple's effective tax rate in Ireland was circa 0.005% for the 2004-2014 period.

Applying a 12.5% rate in a tax code that shields most corporate profits from taxation, is indistinguishable from applying a near 0% rate in a normal tax code.

— Jonathan Weil, Bloomberg View, 11 February 2014

Experts in the Tax Justice Network confirmed that Ireland's effective corporate tax rate was not 12.5%, but closer to the BEA calculation.

It is not just Ireland however. The same BEA calculation showed that

the ETRs of U.S. corporates in other corporate tax havens was also very

low: Luxembourg (2.4%), the Netherlands (3.4%). When tax haven academic Gabriel Zucman,

published a multi-year investigation into corporate tax havens in June

2018, showing that Ireland is the largest global corporate tax haven

(having shielded $106 billion in profits in 2015), and that Ireland's

effective tax rate was 4% (including all non-Irish corporates), the Irish Government countered that they could not be a tax-haven as they are OECD-compliant.

There is a broad consensus that Ireland must defend its 12.5 per cent corporate tax rate. But that rate is defensible only if it is real. The great risk to Ireland is that we are trying to defend the indefensible. It is morally, politically and economically wrong for Ireland to allow vastly wealthy corporations to escape the basic duty of paying tax. If we don’t recognise that now, we will soon find that a key plank of Irish policy has become untenable.

— Irish Times, "Editorial View: Corporate tax: defending the indefensible", 2 December 2017

Financial impact

It is difficult to calculate the financial effect of tax havens in

general due to the obfuscation of financial data. Most estimates have

wide ranges (see financial effect of tax havens).

By focusing on "headline" vs. "effective" corporate tax rates,

researchers have been able to more accurately estimate the annual

financial tax losses (or "profits shifted"), due to corporate tax havens

specifically. This is not easy, however. As discussed above, havens

are sensitive to discussions on “effective” corporate tax rates and

obfuscate data that does not show the "headline" tax rate mirroring the

"effective" tax rate.

Two academic groups have estimated the "effective" tax rates of corporate tax havens using very different approaches:

- 2014 Bureau of Economic Analysis (or BEA) calculation applied to get the "effective" tax rates of U.S. corporates in the haven (per above § Denial of status); and

- 2018 Gabriel Zucman "The Missing Profits of Nations" analysis which uses national accounts data to estimate effective tax rates of all non-domestic corporates in the haven.

They are summarised in the following table for the top eight

corporate tax havens (BVI and the Caymans counted as one), as listed in

Zucman's analysis (from Appendix, table 2).

|

Zucman used this analysis to estimate that the annual financial impact of corporate tax havens was $250 billion in 2015. This is beyond the upper limit of the OECD's 2017 range of $100–200 billion per annum for base erosion and profit shifting activities. These are the most credible and widely quoted sources of the financial impact of corporate tax havens.

The World Bank, in its 2019 World Development Report on the future of work suggests that tax avoidance by large corporations limits the ability of governments to make vital human capital investments.

Conduits and Sinks

Modern corporate tax havens like Ireland, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands have become more popular for U.S. corporate tax inversions than leading traditional tax havens, even Bermuda.

"Uncovering Offshore Financial Centers": Relationship of Conduit and Sink Offshore Financial Centres.

However, corporate tax havens still retain close connections with

traditional tax havens as there are instances where a corporation cannot

"retain" the untaxed funds in the corporate tax haven, and will instead

use the corporate tax haven like a "conduit", to route the funds to

more explicitly zero-tax, and more secretive traditional tax havens.

Google does this with the Netherlands to route EU funds untaxed to

Bermuda (i.e. dutch sandwich to avoid EU withholding taxes), and Russian banks do this with Ireland to avoid international sanctions and access capital markets (i.e. Irish Section 110 SPVs).

A study published in Nature in 2017 (see Conduit and Sink OFCs),

highlighted an emerging gap between corporation tax haven specialists

(called Conduit OFCs), and more traditional tax havens (called Sink

OFCs). It also highlighted that each Conduit OFC was highly connected

to specific Sink OFC(s). For example, Conduit OFC Switzerland was

highly tied to Sink OFC Jersey. Conduit OFC Ireland was tied to Sink

OFC Luxembourg,

while Conduit OFC Singapore was connected to Sink OFCs Taiwan and Hong

Kong (the study clarified that Luxembourg and Hong Kong were more like

traditional tax havens).

The separation of tax havens into Conduit OFCs and Sink OFCs,

enables the corporate tax haven specialist to promote "respectability"

and maintain OECD-compliance (critical to extracting untaxed profits

from higher-taxed jurisdictions via cross-border intergroup IP

charging), while enabling the corporate to still access the benefits of a

full tax haven (via double Irish, dutch sandwich type BEPS tools), as needed.

We increasingly find offshore magic circle law firms, such as Maples and Calder, and Appleby, setting up offices in major Conduit OFCs, such as Ireland.

A key architect [for Apple] was Baker McKenzie, a huge law firm based in Chicago. The firm has a reputation for devising creative offshore structures for multinationals and defending them to tax regulators. It has also fought international proposals for tax avoidance crackdowns. Baker McKenzie wanted to use a local Appleby office to maintain an offshore arrangement for Apple. For Appleby, Mr. Adderley said, this assignment was “a tremendous opportunity for us to shine on a global basis with Baker McKenzie.”

— The New York Times, "After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits", 6 November 2017

Employment tax

Several

modern corporate tax havens, such as Singapore and the United Kingdom,

ask that in return for corporates using their IP-based BEPS tools, they

must perform "work" on the IP in the jurisdiction of the haven. The

corporation thus pays an effective "employment tax" of circa 2-3% by

having to hire staff in the corporate tax haven. This gives the haven more respectability (i.e. not a "brass plate"

location), and gives the corporate additional "substance" against

challenges by taxing authorities. The OECD's Article 5 of the MLI supports havens with "employment taxes" at the expense of traditional tax havens.

Mr. Chris Woo, tax leader at PwC Singapore, is adamant the Republic is not a tax haven. "Singapore has always had clear law and regulations on taxation. Our incentive regimes are substance-based and require substantial economic commitment. For example, types of business activity undertaken, level of headcount and commitment to spending in Singapore", he said.

— The Straits Times, 14 December 2016

Irish IP-based BEPS tools (e.g. the "capital allowances for intangible assets"

BEPS scheme), have the need to perform a "relevant trade" and "relevant

activities" on Irish-based IP, encoded in their leglislation, which

requires specified employment levels and salary levels (discussed here), which roughly equates to an "employment tax" of circa 2-3% of profits (based on Apple and Google in Ireland).

For example, Apple employs 6,000 people in Ireland, mostly in the

Apple Hollyhill Cork plant. The Cork plant is Apple's only

self-operated manufacturing plant in the world (i.e. Apple almost always

contracts to 3rd party manufacturers). It is considered a

low-technology facility, building iMacs to order by hand, and in this

regard is more akin to a global logistics hub for Apple (albeit located

on the "island" of Ireland). No research is carried out in the

facility.

Unusually for a plant, over 700 of the 6,000 employees work from home

(the largest remote percentage of any Irish technology company).

When the EU Commission completed their State aid investigation into Apple, they found Apple Ireland's ETR for 2004–2014, was 0.005%, on over €100bn of globally sourced, and untaxed, profits.

The "employment tax" is, therefore, a modest price to pay for

achieving very low taxes on global profits, and it can be mitigated to

the extent that the job functions are real and would be needed

regardless.

"Employment taxes" are considered a distinction between modern

corporate tax havens, and near-corporate tax havens, like Luxembourg and

Hong Kong (who are classed as Sink OFCs).

The Netherlands has been introducing new "employment tax" type

regulations, to ensure it is seen as a modern corporate tax haven (more

like Ireland, Singapore, and the U.K.), than a traditional tax haven

(e.g. Hong Kong).

The Netherlands is fighting back against its reputation as a tax haven with reforms to make it more difficult for companies to set up without a real business presence. Menno Snel, the Dutch secretary of state for finance, told parliament last week that his government was determined to “overturn the Netherlands’ image as a country that makes it easy for multinationals to avoid taxation”.

— Financial Times, 27 February 2018

U.K. transformation

The United Kingdom was traditionally a "donor" to corporate tax havens (e.g. the last one being Shire plc's tax inversion to Ireland in 2008).

However, the speed at which the U.K. changed to becoming one of the

leading modern corporate tax havens (at least up until pre-Brexit), makes it an interesting case (it still does not appear on all § Corporate tax haven lists).

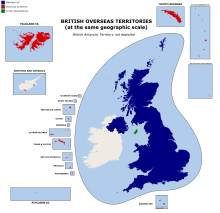

British

Overseas Territories (same geographic scale) includes leading

traditional and corporate global tax havens including the Caymans, the

BVI and Bermuda, as well as the U.K. itself.

The U.K. changed its tax regime in 2009–2013. It lowered its

corporate tax rate to 19%, brought in new IP-based BEPS tools, and moved

to a territorial tax system. The U.K. became a "recipient" of U.S. corporate tax inversions, and ranked as one of Europe's leading havens. A major study now ranks the U.K. as the second largest global Conduit OFC (a corporate haven proxy). The U.K. was particularly fortunate as 18 of the 24 jurisdictions that are identified as Sink OFCs, the traditional tax havens, are current or past dependencies of the U.K. (and embedded into U.K. tax and legal statute books).

New IP legislation was encoded into the U.K. statute books and the concept of IP significantly broadened in U.K. law. The U.K.'s Patent Office was overhauled and renamed the Intellectual Property Office. A new U.K. Minister for Intellectual Property was announced with the 2014 Intellectual Property Act. The U.K. is now 2nd in the 2018 Global IP Index.

A growing array of tax benefits have made London the city of choice for big firms to put everything from “letterbox” subsidiaries to full-blown headquarters. A loose regime for “controlled foreign corporations” makes it easy for British-registered businesses to park profits offshore. Tax breaks on income from patents [IP] are more generous than almost anywhere else. Britain has more tax treaties than any of the three countries [Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Ireland] on the naughty step—and an ever-falling corporate-tax rate. In many ways, Britain is leading the race to the bottom.

— The Economist, "Still slipping the net", 8 October 2015

The U.K.'s successful transformation from "donor" to corporate tax

havens, to a major global corporate tax haven in its own right, was

quoted as a blueprint for type of changes that the U.S. needed to make

in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 tax reforms (e.g. territorial system, lower headline rate, benefitical IP-rate).

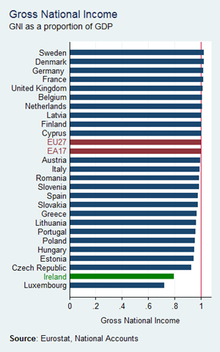

Distorted GDP/GNP

"EU 2011 Ratio of GNI to GDP" (Eurostat National Accounts, 2011)

Some leading modern corporate tax havens are synonymous with offshore financial centres (or OFCs), as the scale of the multinational flows rivals their own domestic economies (the IMF's sign of an OFC).

The American Chamber of Commerce Ireland estimated that the value of

U.S. investment in Ireland was €334bn, exceeding Irish GDP (€291bn in

2016). An extreme example was Apple's "onshoring" of circa $300 billion in intellectual property to Ireland, creating the leprechaun economics affair. However Luxembourg's GNI is only 70% of GDP. The distortion of Ireland's economic data from corporates using Irish IP-based BEPS tools (especially the capital allowances for intangible assets tool), is so great, that it distorts EU-28 aggregate data.

A stunning $12 trillion—almost 40 percent of all foreign direct investment positions globally—is completely artificial: it consists of financial investment passing through empty corporate shells with no real activity. These investments in empty corporate shells almost always pass through well-known tax havens. The eight major pass-through economies—the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong SAR, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Ireland, and Singapore—host more than 85 percent of the world’s investment in special purpose entities, which are often set up for tax reasons.

— "Piercing the Veil", International Monetary Fund, June 2018

This distortion means that all corporate tax havens, and particularly

smaller ones like Ireland, Singapore, Luxembourg and Hong Kong, rank at

the top in global GDP-per-capita league tables. In fact, not being a county with oil & gas resources and still ranking in the top 10 of world GDP-per-capita league tables, is considered a strong proxy sign of a corporate (or traditional) tax haven. GDP-per-capita tables with identification of haven types are here § GDP-per-capita tax haven proxy.

Ireland's distorted economic statistics, post leprechaun economics and the introduction of modified GNI, is captured on page 34 of the OECD 2018 Ireland survey:

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GDP basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 78.8% is not of concern;

- On a Gross Public Debt-to-GNI* basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at 116.5% is more serious, but not alarming;

- On a Gross Public Debt Per Capita basis, Ireland's 2015 figure at over $62,686 per capita, exceeds every other OECD country, except Japan.

This distortion leads to exaggerated credit cycles. The

artificial/distorted "headline" GDP growth increases optimism and

borrowing in the haven, which is financed by global capital markets (who

are misled by the artificial/distorted "headline" GDP figures and

misprice the capital provided). The resulting bubble in asset/property

prices from the build-up in credit can unwind quickly if global capital

markets withdraw the supply of capital. Extreme credit cycles have been seen in several of the corporate tax havens (i.e. Ireland in 2009-2012 is an example). Traditional tax havens like Jersey have also experienced this.

The statistical distortions created by the impact on the Irish National Accounts of the global assets and activities of a handful of large multinational corporations [during leprechaun economics] have now become so large as to make a mockery of conventional uses of Irish GDP.

— Patrick Honohan, ex-Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland, 13 July 2016

IP–based BEPS tools

John Oliver, who made an HBO program on IP-based BEPS tools.

Raw materials of tax avoidance

Whereas traditional corporate tax havens facilitated avoiding domestic taxes (e.g. U.S. corporate tax inversion), modern corporate tax havens provide base erosion and profit shifting (or BEPS) tools, which facilitate avoiding taxes in all global jurisdictions in which the corporation operates. This is as long as the corporate tax haven has tax-treaties with the jurisdictions that accept "royalty payment" schemes (i.e. how the IP is charged out), as a deduction against tax.

A crude indicator of a corporate tax haven is the amount of full

bilateral tax treaties that it has signed. The U.K. is the leader with

over 122, followed by the Netherlands with over 100.

BEPS tools abuse intellectual property (or IP), GAAP accounting techniques, to create artificial internal intangible assets, which facilitate BEPS actions, via:

- Royalty payment schemes, used to route untaxed funds to the haven, by charging-out the IP as a tax-deductible expense to the higher-tax jurisdictions; and/or

- Capital allowance for intangible assets schemes, used to avoid corporate taxes within the haven, by allowing corporates write-off their IP against tax.

IP is described as the “raw material” of tax planning. Modern corporate tax havens have IP-based BEPS tools, and are in all their bilateral tax-treaties. IP is a powerful tax management and BEPS tool, with almost no other equal, for four reasons:

- Hard to value. IP made in a U.S. R&D laboratory, can be sold to the group's Caribbean subsidiary for a small sum (and a tiny U.S. taxable gain is realised), but then repackaged and revalued upwards by billions after an expensive valuation audit by a major accounting firm (from a corporate tax haven);

- Perpetually replenishable. The firms that have IP (i.e. Google, Apple, Facebook), have "product cycles" where new versions/new ideas emerge. This product cycle thus creates new IP which can replace older IP that has been used up and/or written-off against taxes;

- Very mobile. Because IP is a virtual asset which only exists in contracts (i.e. on paper), it is easy to move/relocate around the world; it can be restructured into vehicles that provide secrecy and confidentiality around the scale, ownership, and location, of the IP;

- Accepted as an intergroup charge. Many jurisdictions accept IP royalty payments as a deductible against tax, even intergroup charges; Google Germany is unprofitable because of intergroup IP royalties it pays Google Bermuda (via Google Ireland), which is profitable.

When corporate tax havens quote "effective rates of tax", they

exclude large amounts of income not considered taxable due to the

IP-based tools. Thus, in a self-fulfilling manner, their "effective"

tax rates equal their "headline" tax rates. As discussed earlier (§ Denials of status),

Ireland claims an "effective" tax rate of circa 12.5%, while the

IP-based BEPS tools used by Ireland's largest companies, mostly U.S.

multinationals, are marketed with effective tax rates of <0-3 0-3="" above="" and="" apple="" been="" commission="" eu="" have="" in="" investigation="" of="" other="" p="" rates="" s="" see="" sources.="" the="" these="" verified="">

"It is hard to imagine any business, under the current [Irish] IP regime, which could not generate substantial intangible assets under Irish GAAP that would be eligible for relief under [the Irish] capital allowances [for intangible assets scheme]." "This puts the attractive 2.5% Irish IP-tax rate within reach of almost any global business that relocates to Ireland."

— KPMG, "Intellectual Property Tax", 4 December 2017

Encoding IP–based BEPS tools

The creation of IP-based BEPS tools requires advanced legal and tax

structuring capabilities, as well as a regulatory regime willing to

carefully encode the complex legislation into the jurisdiction's statute

books (note that BEPS tools bring increased risks of tax abuse by the

domestic tax base in corporate tax haven's own jurisdiction, see § Irish Section 110 SPV for an example).

Modern corporate tax havens, therefore, tend to have large global

legal and accounting professional service firms in-situ (many classical

tax havens lack this) who work with the government to build the

legislation. In this regard, havens are accused of being captured states by their professional services firms. The close relationship between Ireland's International Financial Services Centre professional service firms and the State in Ireland, is often described as the "green jersey agenda". The speed at which Ireland was able to replace its double Irish IP-based BEPS tool, is a noted example.

It was interesting that when [Member of European Parliament, MEP] Matt Carthy put that to the [Finance] Minister's predecessor (Michael Noonan), his response was that this was very unpatriotic and he should wear the "green jersey". That was the former Minister's response to the fact there is a major loophole, whether intentional or unintentional, in our tax code that has allowed large companies to continue to use the double Irish [the "single malt"].

It is considered that this type of legal and tax work is beyond the normal trust-structuring of offshore magic circle-type firms.

This is substantive and complex leglislation that needs to integrate

with tax treaties that involve G20 jurisdictions, as well as advanced

accounting concepts that will meet U.S. GAAP, SEC and IRS regulations

(U.S. multinationals are leading users of IP-based BEPS tools). It is also why most modern corporate tax havens started as financial centres,

where a critical mass of advanced professional services firms develop

around complex financial structuring (almost half of the main 10

corporate tax havens are in the 2017 top 10 Global Financial Centres Index, see § Corporate tax haven lists).

"Why should Ireland be the policeman for the US?" he asks. "They can change the law like that!" He snaps his fingers. "I could draft a bill for them in an hour." "Under no circumstances is Ireland a tax haven. I'm a player in this game and we play by the rules." said PwC Ireland International Financial Services Centre Managing Partner, Feargal O'Rourke

— Jesse Drucker, Bloomberg, "Man Making Ireland Tax Avoidance Hub Proves Local Hero", 28 October 2013

That is until the former venture-capital executive at ABN Amro Holding NV Joop Wijn becomes [Dutch] State Secretary of Economic Affairs in May 2003. It's not long before the Wall Street Journal reports about his tour of the US, during which he pitches the new Netherlands tax policy to dozens of American tax lawyers, accountants and corporate tax directors. In July 2005, he decides to abolish the provision that was meant to prevent tax dodging by American companies [the Dutch Sandwich], in order to meet criticism from tax consultants.

— Oxfam/De Correspondent, "How the Netherlands became a Tax Haven", 31 May 2017.

The EU Commission has been trying to break the close relationship in

the main EU corporate tax havens (i.e. Ireland, the Netherlands,

Luxembourg, Malta and Cyprus; the main Conduit and Sink OFCs in the EU-28, post Brexit),

between law and accounting advisory firms, and their regulatory

authorities (including taxing and statistical authorities) from a number

of approaches:

- EU Commission State aid cases, such as the €13 billion fine on Apple in Ireland for Irish taxes avoided, despite protests from the Irish Government and the Irish Revenue Commissioners;

- EU Commission regulations on advisory firms, the most recent example being of the new disclosure rules on regarding "potentially aggressive" tax schemes from 2020 onwards.

The "Knowledge Economy"

Modern

corporate havens present IP-based BEPS tools as "innovation economy",

"new economy" or "knowledge economy" business activities (e.g. some use the term "knowledge box" or "patent box"

for a class of IP-based BEPS tools, such as in Ireland and in the

U.K.), however, their development as a GAAP accounting entry, with few

exceptions, is for the purposes of tax management.

Intellectual property (IP) has become the leading tax-avoidance vehicle.

— UCLA Law Review, "Intellectual Property Law Solutions to Tax Avoidance" (2015)

When Apple "onshored" $300 billion of IP to Ireland in 2015 (leprechaun economics), the Irish Central Statistics Office suppressed its regular data release to protect the identity of Apple (unverifiable for 3 years, until 2018),

but then described the artificial 26.3% rise in Irish GDP as "meeting

the challenges of a modern globalised economy" (the CSO was described as

putting on the "green jersey").

Leprechaun economics an example of how Ireland was able to meet with

the OECD's transparency requirements (and score well in the Financial Secrecy Index), and still hide the largest BEPS action in history.

As noted earlier (§ U.K. transformation), the U.K. has a Minister for Intellectual Property and an Intellectual Property Office, as does Singapore (Intellectual Property Office of Singapore). The top 10 list of the 2018 Global Intellectual Property Center

IP Index, the leaders in IP management, features the five largest

modern corporate tax havens: United Kingdom (#2), Ireland (#6), the

Netherlands (#7), Singapore (#9) and Switzerland (#10).

This is despite the fact that patent-protection has traditionally been

synonymous with the largest, and longest established, legal

jurisdictions (i.e. mainly older G7-type countries).

German "Royalty Barrier" failure

In

June 2017, the German Federal Council approved a new law called an IP

"Royalty Barrier" (Lizenzschranke) that restricts the ability of

corporates to deduct intergroup cross-border IP charges against German

taxation (and also encourage corporates to allocate more employees to

Germany to maximise German tax-relief). The law also enforces a minum

"effective" 25% tax rate on IP.

While there was initial concern amongst global corporate tax advisors

(who encode the IP leglislation) that a "Royalty Barrier" was the

"beginning of the end" for IP-based BEPS tools,

the final law was instead a boost for modern corporate tax havens,

whose OECD-compliant, and more carefully encoded and embedded IP tax

regimes, are effectively exempted. More traditional corporate tax

havens, which do not always have the level of sophistication and skill

in encoding IP BEPS tools into their tax regimes, will fall further

behind.

The German "Royalty Barrier" law exempts IP charged from locations which have:

- OECD-nexus compliant "knowledge box" BEPS tools. Ireland was the first corporate tax haven to introduce this in 2015, and the others are following Ireland's lead.

- Tax regimes where there is no "preferential treatment" of IP. Modern corporate tax havens apply the full "headline" rate to all IP, but then achieve lower "effective" rates via BEPS tools.

One of Ireland's main tax law firms, Matheson, whose clients include some of the largest U.S. multinationals in Ireland,

issued a note to its clients confirming that the new German "Royalty

Barrier" will have little effect on their Irish IP-based BEPS structures

- despite them being the primary target of the law. In fact, Matheson notes that that new law will further highlight Ireland's "robust solution".

However, given the nature of the Irish tax regime, the [German] royalty barrier should not impact royalties paid to a principal licensor resident in Ireland.

Ireland's BEPS-compliant tax regime offers taxpayers a competitive and robust solution in the context of such unilateral initiatives.

— Matheson, "Germany: Breaking Down The German Royalty Barrier - A View From Ireland", 8 November 2017

The failure of the German "Royalty Barrier" approach is a familiar

route for systems that attempt to curb corporate tax havens via an

OECD-compliance type approach (see § Failure of OECD BEPS Project), which is what modern corporate tax havens are distinctive in maintaining. It contrasts with the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017,

which ignores whether a jurisdiction is OECD compliant (or not), and

instead focuses solely on "effective taxes paid", as its metric. Had

the German "Royalty Barrier" taken the U.S. approach, it would have been

more onerous for havens. Reasons for why the barrier was designed to

fail is discussed in complex agendas.

IP and post-tax margins

The

sectors most associated with IP (e.g., technology and life sciences)

are generally the some of the most profitable corporate sectors in the

world. By using IP-based BEPS tools, these profitable sectors have

become even more profitable on an after-tax basis by artificially

suppressing profitability in higher-tax jurisdictions, and profit

shifting to low-tax locations.

For example, Google Germany should be even more profitable than

the already very profitable Google U.S. This is because the marginal

additional costs for firms like Google U.S. of expanding into Germany

are very low (the core technology platform has been built). In

practice, however, Google Germany is actually unprofitable (for tax

purposes), as it pays intergroup IP charges back to Google Ireland, who

reroutes them to Google Bermuda, who is extremely profitable (more so

than Google U.S.). These intergroup IP charges (i.e. the IP-based BEPS tools), are artificial internal constructs.

Commentators have linked the cyclical peak in U.S. corporate

profit margins, with the enhanced after-tax profitability of the biggest

U.S. technology firms.

For example, the definitions of IP in corporate tax havens such

as Ireland has been broadened to include "theoretical assets", such as

types of general rights, general know-how, general goodwill, and the

right to use software.

Ireland's IP regime includes types of "internally developed"

intangible assets and intangible assets purchased from "connected

parties". The real control in Ireland is that the IP assets must be

acceptable under GAAP (older 2004 Irish GAAP is accepted), and thus

auditable by an Irish International Financial Services Centre accounting firm.

A broadening range of multinationals are abusing IP accounting to

increase after-tax margins, via intergroup charge-outs of artificial IP

assets for BEPS purposes, including:

- Amazon, a retailer, used it in Luxembourg.

- Starbucks, a coffee chain, also used it in Luxembourg.

- Apple, a phone manufacturer, used it in Ireland.

It has been noted that IP-based BEPS tools such as the "patent box" can be structured to create negative rates of taxation for IP-heavy corporates.

IP–based Tax inversions

Apple's Q1 2015 Irish "quasi-inversion" of its $300bn international IP (known as leprechaun economics),

is the largest recorded individual BEPS action in history, and almost

double the 2016 $160bn Pfizer-Allergan Irish inversion, which was

blocked.

Brad Setser & Cole Frank

(Council on Foreign Relations)

Brad Setser & Cole Frank

(Council on Foreign Relations)

Apple vs. Pfizer–Allergan

Modern

corporate tax havens further leverage their IP-based BEPS toolbox to

enable international corporates to execute quasi-tax inversions, which

could otherwise be blocked by domestic anti-inversion rules. The

largest example was Apple's Q1 January 2015 restructuring of its Irish

business, Apple Sales International, in a quasi-tax inversion, which led

to the Paul Krugman labeled "leprechaun economics" affair in Ireland in July 2016 (see article).

In early 2016, the Obama Administration blocked the proposed $160 billion Pfizer-Allergan Irish corporate tax inversion, the largest proposed corporate tax inversion in history, a decision which the Trump Administration also updeld.

However, both Administrations were silent when the Irish State

announced in July 2016 that 2015 GDP has risen 26.3% in one quarter due

to the "onshoring" of corporate IP, and it was rumoured to be Apple. It might have been due to the fact that the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) openly delayed and limited its normal data release to protect the confidentiality of the source of the growth. It was only in early 2018, almost three years after Apple's Q1 2015 $300 billion quasi-tax inversion to Ireland (the largest tax inversion in history), that enough Central Statistics Office (Ireland) data was released to prove it definitively was Apple.

Financial commentators estimate Apple onshored circa $300 billion

in IP to Ireland, effectively representing the balance sheet of Apple's

non-U.S. business.

Thus, Apple completed a quasi-inversion of its non-U.S. business, to

itself, in Ireland, which was almost twice the scale of

Pfizer-Allergan's $160 billion blocked inversion.

Apple's IP–based BEPS inversion

Apple used Ireland's new BEPS tool, and "double Irish" replacement, the "capital allowances for intangible assets" scheme.

This BEPS tool enables corporates to write-off the "arm's length" (to

be OECD-compliant), intergroup acquisition of offshored IP, against all

Irish corporate taxes. The “arm’s length” criteria are achieved by

getting a major accounting firm in Ireland's International Financial Services Centre to conduct a valuation, and Irish GAAP audit, of the IP. The range of IP acceptable by the Irish Revenue Commissioners is very broad. This BEPS tool can be continually replenished by acquiring new offshore IP with each new "product cycle".

In addition, Ireland's 2015 Finance Act removed the 80% cap on this tool (which forced a minimum 2.5% effective tax rate), thus giving Apple a 0% effective tax rate on the "onshored" IP. Ireland then restored the 80% cap in 2016 (and a return to a minimum 2.5% effective tax rate), but only for new schemes.

Thus, Apple was able to achieve what Pfizer-Allergan could not,

by making use of Ireland's advanced IP-based BEPS tools. Apple avoided

any U.S regulatory scrutiny/blocking of its actions, as well as any

wider U.S. public outcry, as Pfizer-Allergan incurred. Apple structured

an Irish corporate effective tax rate of close to zero on its non-U.S. business, at twice the scale of the Pfizer-Allergan inversion.

I cannot see a justification for giving full Irish tax relief to the intragroup acquisition of a virtual asset, except that it is for the purposes of facilitating corporate tax avoidance.

— Professor Jim Stewart, Trinity College Dublin, "MNE Tax Strategies in Ireland", 2016

Debt–based BEPS tools

Dutch "Double Dip"

Ex. Dutch Minister Joop Wijn credited with introducing the Dutch Sandwich IP-based BEPS tool (which is often used with the Double Irish BEPS tool), and the "Dutch Double Dip" Debt-based BEPS tool

While the focus of corporate tax havens continues to be on developing

new IP-based BEPS tools (such as OECD-compliant knowledge/patent

boxes), Ireland has developed new BEPS tools leveraging traditional securitisation SPVs, called Section 110 SPVs.

Use of intercompany loans and loan interest was one of the original

BEPS tools and was used in many of the early U.S. corporate tax inversions (was known as "earnings-stripping").

The Netherlands has been a leader in this area, using

specifically worded legislation to enable IP-light companies further

amplify "earnings-stripping". This is used by mining and resource

extraction companies, who have little or no IP, but who use high levels

of leverage and asset financing.

Dutch tax law enables IP-light companies to "overcharge" their

subsidiaries for asset financing (i.e. reroute all untaxed profits back

to the Netherlands), which is treated as tax-free in the Netherlands.

The technique of getting full tax-relief for an artificially

high-interest rate in a foreign subsidiary, while getting additional tax

relief on this income back home in the Netherlands, became known by the

term, "double dipping". As with the Dutch sandwich, ex. Dutch Minister Joop Wijn is credited as its creator.

In 2006 he [ Joop Wijn ] abolished another provision meant to prevent abuse, this one pertaining to hybrid loans. Some revenue services classify those as loans, while others classify those as capital, so some qualify payments as interest, others as profits. This means that if a Dutch company provides such a hybrid [and very high interest] loan to a foreign company, the foreign company could use the payments as a tax deduction, while the Dutch company can classify it as profit from capital, which is exempt from taxes in the Netherlands [called "double dipping"]. This way no taxes are paid in either country.

— Oxfam/De Correspondent, "How the Netherlands became a Tax Haven", 31 May 2017.

Irish Section 110 SPV

Stephen Donnelly TD

Estimated US distressed funds used Section 110 SPVs to avoid €20

billion in Irish taxes on almost €80 billion of Irish domestic

investments from 2012–2016.

The Irish Section 110 SPV uses complex securitisation loan structuring (including "orphaning" which adds confidentiality), to enable the profit shifting. This tool is so powerful, it inadvertently enabled US distressed debt funds avoid billions in Irish taxes on circa €80 billion of Irish investments they made in 2012-2016 (see Section 110 abuse). This was despite the fact that the seller of the circa €80 billion was mostly the Irish State's own National Asset Management Agency.

The global securitisation market is circa $10 trillion in size,

and involves an array of complex financial loan instruments, structured

on assets all over the world, using established securitization vehicles

that are accepted globally (and whitelisted by the OECD). This is also

helpful for concealing corporate BEPS activities, as demonstrated by

sanctioned Russian banks using Irish Section 110 SPVs.

This area is therefore an important new BEPS tool for EU corporate tax havens, Ireland and Luxembourg, who are also the EU's leading securitisation hubs. Particularly so, given the new anti-IP-based BEPS tool taxes of the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), (i.e. the new GILTI tax regime and BEAT tax regime), and proposed EU Digital Services Tax (DST) regimes.

The U.S. TCJA anticipates a return to debt-based BEPS tools, as

it limits interest deductibility to 30% of EBITDA (moving to 30% of EBIT

post 2021).

While securitisation

SPVs are important new BEPS tools, and acceptable under global

tax-treaties, they suffer from "substance" tests (i.e. challenges by tax

authorities that the loans are artificial). Irish Section 110 SPV's

use of "Profit Participation Notes"

(i.e. artificial internal intergroup loans), is an impediment to

corporates using these structures versus established IP-based BEPS

tools. Solutions such as the Orphaned Super-QIAIF have been created in the Irish tax code to resolve this.

However, while Debt-based BEPS tools may not feature with U.S.

multinational technology companies, they have become attractive to

global financial institutions (who do not need to meet the same

"substance" tests on their financial transactions).

In February 2018, the Central Bank of Ireland upgraded the little-used Irish L-QIAIF

regime to offer the same tax benefits as Section 110 SPVs but without

the need for Profit Participation Notes and without the need to file

public accounts with the Irish CRO (which had exposed the scale of Irish domestic taxes Section 110 SPVs had been used to avoid, see abuses).

Ranking corporate tax havens

Proxy tests

The study and identification of modern corporate tax havens are still developing. Traditional qualitative-driven IMF-OCED-Financial Secrecy Index

type tax haven screens, which focus on assessing legal and tax

structures, are less effective given the high levels of transparency and

OECD-compliance in modern corporate tax havens (i.e. most of their BEPS

tools are OECD-whitelisted).

- A proposed test of a modern corporate tax haven is the existence of regional headquarters of major U.S. technology multinationals (largest IP-based BEPS tool users) such as Apple, Google or Facebook. The main EMEA jurisdictions for headquarters are Ireland, and the United Kingdom, while the main APAC jurisdictions for headquarters is Singapore.

- A proposed proxy are jurisdictions to which U.S. corporates execute tax inversions (see § Bloomberg Corporate tax inversions). Since the first U.S. corporate tax inversion in 1982, Ireland has received the most U.S. inversions, with Bermuda second, the United Kingdom third and the Netherlands fourth. Since 2009, Ireland and the United Kingdom have dominated.

- The 2017 report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy on offshore activities of U.S. Fortune 500 companies, lists the Netherlands, Singapore, Hong Kong, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Ireland and the Caribbean triad (the Cayman-Bermuda-BVI), as the places where Fortune 500 companies have the most subsidiaries (note: this does not estimate the scale of their activities).

- Zucman, Tørsløv, and Wier advocate profitability of U.S. corporates in the haven as a proxy. This is particularly useful for havens that use the § Employment tax system and require corporates to maintain a "substantive" presence in the haven for respectability. Ireland is the most profitable location, followed by the Caribbean (incl. Bermuda), Luxembourg, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

- The distortion of national accounts by the accounting flows of particular IP-based BEPS tools is a proxy. This was spectacularly shown in Q1 2015 during Apple's leprechaun economics. The non-Oil & Gas nations in the top 15 List of countries by GDP (PPP) per capita are tax havens led by Luxembourg, Singapore and Ireland (see § GDP-per-capita tax haven proxy).

- A related but similar test is the ratio of GNI to GDP, as GNI is less prone to distortion by IP-based BEPS tools. Countries with low GNI/GDP ratio (e.g. Luxembourg, Ireland and Singapore) are almost always tax havens. However, not all havens have low GNI/GDP ratios. Example being the Netherlands, whose dutch sandwich BEPS tool impacts their national accounts in a different way.

- The use of “common law” legal systems, whose structure gives greater legal protection to the construction of corporate tax “loopholes” by the jurisdiction (e.g. the double Irish, or trusts), is sometimes proposed. There is a disproportionate concentration of common law systems amongst corporate tax havens, including Ireland, the U.K., Singapore, Hong Kong, most Caribbean (e.g. the Caymans, Bermuda, and the BVI). However it is not conclusive, as major havens, Luxembourg and the Netherlands run “civil law” systems. Many havens are current, or past U.K. dependencies.

Quantitative measures

More scientific, are the quantitative-driven studies (focused on

empirical outcomes), such as the work by the University of Amsterdam's

CORPNET in Conduit and Sink OFCs, and by University of Berkley's Gabriel Zucman. They highlight the following modern corporate tax havens, also called Conduit OFCs, and also highlight their "partnerships" with key traditional tax havens, called Sink OFCs:

Netherlands - the "mega" Conduit OFC, and focused on moving funds from the EU (via the "dutch sandwich" BEPS tool) to Luxembourg and the "triad" of Bermuda/BVI/Cayman.

Netherlands - the "mega" Conduit OFC, and focused on moving funds from the EU (via the "dutch sandwich" BEPS tool) to Luxembourg and the "triad" of Bermuda/BVI/Cayman. Great Britain

- 2nd largest Conduit OFC and the link from Europe to Asia; 18 of the

24 Sink OFCs are current, or past, dependencies of the U.K.

Great Britain

- 2nd largest Conduit OFC and the link from Europe to Asia; 18 of the

24 Sink OFCs are current, or past, dependencies of the U.K. Switzerland - long-established corporate tax haven and a major Conduit OFC for Jersey, one of the largest established offshore tax havens.

Switzerland - long-established corporate tax haven and a major Conduit OFC for Jersey, one of the largest established offshore tax havens. Singapore

- the main Conduit OFC for Asia, and the link to the two major Asian

Sink OFCs of Hong Kong and Taiwan (Taiwan is described as the

Switzerland of Asia).

Singapore

- the main Conduit OFC for Asia, and the link to the two major Asian

Sink OFCs of Hong Kong and Taiwan (Taiwan is described as the

Switzerland of Asia). Ireland - the main Conduit OFC for U.S. links (see Ireland as a tax haven), who make heavy use of Sink OFC Luxembourg as a backdoor out of the Irish corporate tax system.

Ireland - the main Conduit OFC for U.S. links (see Ireland as a tax haven), who make heavy use of Sink OFC Luxembourg as a backdoor out of the Irish corporate tax system.

The only jurisdiction from the above list of major global corporate

tax havens that makes an occasional appearance in OECD-IMF tax haven

lists is Switzerland. These jurisdictions are the leaders in IP-based

BEPS tools and use of intergroup IP charging and have the most

sophisticated IP legislation. They have the largest tax treaty networks

and all follow the § Employment tax approach.

The analysis highlights the difference between "suspected"

onshore[tax havens (i.e. major Sink OFCs Luxembourg and Hong Kong),

which because of their suspicion, have limited/restricted bilateral tax

treaties (as countries are wary of them), and the Conduit OFCs, which

have less "suspicion" and therefore the most extensive bilateral tax

treaties. Corporates need the broadest tax treaties for their BEPS

tools, and therefore prefer to base themselves in Conduit OFCs (Ireland

and Singapore), which can then route the corporate's funds to the Sink

OFCs (Luxembourg and Hong Kong).

"Uncovering

Offshore Financial Centers": List of Sink OFCs by value (highlighting

the current and ex. U.K. dependencies, in light blue)

Of the major Sink OFCs, they span a range between traditional tax

havens (with very limited tax treaty networks) and near-corporate tax

havens:

British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands  Bermuda

Bermuda  Cayman Islands

- The Caribbean "triad" of Bermuda/BVI/Cayman are classic major tax

havens, and therefore with limited access to full global tax treaty

networks, thus relying on Conduit OFCs for access; heavily used by U.S.

multinationals.

Cayman Islands

- The Caribbean "triad" of Bermuda/BVI/Cayman are classic major tax

havens, and therefore with limited access to full global tax treaty

networks, thus relying on Conduit OFCs for access; heavily used by U.S.

multinationals. Luxembourg

- noted by CORPNET as being close to a Conduit, however, U.S. firms are

more likely to use Ireland/U.K. as their Conduit OFC to Luxembourg.

Luxembourg

- noted by CORPNET as being close to a Conduit, however, U.S. firms are

more likely to use Ireland/U.K. as their Conduit OFC to Luxembourg. Hong Kong - often described as the "Luxembourg of Asia"; U.S. firms are more likely to use Singapore as their Conduit OFC to route to Hong Kong.

Hong Kong - often described as the "Luxembourg of Asia"; U.S. firms are more likely to use Singapore as their Conduit OFC to route to Hong Kong.

The above five corporate tax haven Conduit OFCs, plus the three

general tax haven Sink OFCs (counting the Caribbean "triad" as one major

Sink OFC), are replicated at the top 8-10 corporate tax havens of many

independent lists, including the Oxfam list, and the ITEP list.

Ireland as global leader

Gabriel Zucman's

analysis differs from most other works in that it focuses on the total

quantum of taxes shielded. He shows that many of Ireland's U.S.

multinationals, like Facebook, don't appear on Orbis (the source for

quantitative studies, including CORPNET's) or have a small fraction of

their data on Orbis (Google and Apple).

Analysed using a "quantum of funds" method (not an "Orbis

corporate connections" method), Zucman shows Ireland as the largest

EU-28 corporate tax haven, and the major route for Zucman's estimated

annual loss of 20% in EU-28 corporate tax revenues.

Ireland exceeds the Netherlands in terms of "quantum" of taxes

shielded, which would arguably make Ireland the largest global corporate

tax haven (it even matches the combined Caribbean triad of

Bermuda-British Virgin Islands-the Cayman Islands).

Failure of OECD BEPS Project

Reasons for the failure

Of the wider tax environment, O’Rourke thinks the OECD base-erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) process is “very good” for Ireland. “If BEPS sees itself to a conclusion, it will be good for Ireland.”Feargal O'Rourke CEO PwC (Ireland).

"Architect" of the famous Double Irish IP-based BEPS tool.

Irish Times, May 2015.

The rise of modern corporate tax havens, like the United Kingdom, the

Netherlands, Ireland and Singapore, contrasts with the failure of OECD

initiatives to combat global corporate tax avoidance and BEPS

activities. There are many reasons advocated for the OECD's failure,

the most common being:

Pierre Moscovici

EU Commissioner for Taxes, whose Digital Services Tax aims to force a

minimum level of EU taxation on technology multinationals operating in

the EU-28.

- Slowness and

predictability. OECD works in 5-10 year cycles, giving havens time to

plan new OECD-compliant BEPS tools (i.e. replacement of double Irish), and corporates the degree of near-term predictability that they need to manage their affairs and not panic (i.e. double Irish only closes in 2020).

Figures released in April 2017 show that since 2015 [when the double Irish was closed to new schemes] there has been a dramatic increase in companies using Ireland as a low-tax or no-tax jurisdiction for intellectual property (IP) and the income accruing to it, via a nearly 1000% increase in the uptake of a tax break expanded between 2014 and 2017 [the capital allowances for intangible assets BEPS tool].

— Christian Aid, "Impossible Structures: tax structures overlooked in the 2015 spillover analysis", 2017 - Bias to modern havens. The OECD's June 2017 MLI was signed by 70 jurisdictions. The corporate tax havens opted out of the key articles (i.e. Article 12), while emphasising their endorsement of others (especially Article 5 which benefits corporate havens using the § Employment tax

BEPS system). Modern corporate tax havens like Ireland and Singapore

used the OECD to diminish other corporate tax havens like Luxembourg and

Hong Kong.

The global legal firm Baker McKenzie, representing a coalition of 24 multinational US software firms, including Microsoft, lobbied Michael Noonan, as [Irish] minister for finance, to resist the [OECD MLI] proposals in January 2017.

In a letter to him the group recommended Ireland not adopt article 12, as the changes “will have effects lasting decades” and could “hamper global investment and growth due to uncertainty around taxation”. The letter said that “keeping the current standard will make Ireland a more attractive location for a regional headquarters by reducing the level of uncertainty in the tax relationship with Ireland’s trading partners”.

— Irish Times. "Ireland resists closing corporation tax ‘loophole’", 10 November 2017. - Focus

on transparency and compliance vs. net tax paid. Most of the OECD's

work focuses on traditional tax havens where secrecy (and criminality)

are issues. The OECD defends modern corporate tax havens to confirm

that they are "not tax havens" due to their OECD-compliance and

transparency. The almost immediate failure of the 2017 German "Royalty Barrier" anti-IP legislation, is a notable example of this:

However, given the nature of the Irish tax regime, the royalty barrier should not impact royalties paid to a principal licensor resident in Ireland.

Ireland's [OECD] BEPS-compliant tax regime offers taxpayers a competitive and robust solution in the context of such unilateral initiatives.

— Matheson, "Germany: Breaking Down The German Royalty Barrier - A View From Ireland", 8 November 2017 - Defence of intellectual property as an intergroup charge. The OECD spent decades developing IP as a legal and accounting concept. The rise in IP, and particularly intergroup IP charging, as the main BEPS tool is incompatible with this position. Ireland has created the first OECD-nexus compliant "knowledge box" (or KDB), which will be amended, as Ireland did with other OECD-whitelist structures, to become a BEPS tool.

IP-related tax benefits are not about to disappear. In fact, [the OECD] BEPS [Project] will help to regularise some of them, albeit in diluted form. Perversely, this is encouraging countries that previously shunned them to give them a try.

— The Economist, "Patently problematic", August 2015

It has been noted in the OECD's defence, that G8 economies like the

U.S. were strong supporters of the OECD's IP work, as they saw it as a

tool for their domestic corporates (especially IP-heavy technology and

life sciences firms), to charge-out US-based IP to international markets

and thus, under U.S. bilateral tax treaties, remit untaxed profits back

to the U.S. However, when U.S. multinationals perfected these IP-based

BEPS tools and worked out how to relocate them to zero-tax places such

as the Caribbean or Ireland, the U.S. became less supportive (i.e. U.S.

2013 Senate investigation into Apple in Bermuda).

However, the U.S. lost further control when corporate havens such

as Ireland, developed "closed-loop" IP-based BEPS systems, like the capital allowances for intangibles tool, which by-pass U.S. anti-Corporate tax inversion controls, to enable any U.S. firm (even IP-light firms) create a synthetic corporate tax inversion (and achieve 0-3% Irish effective tax rates), without ever leaving the U.S. Apple's successful $300 Q1 2015 billion IP-based Irish tax inversion (which came to be known as leprechaun economics), compares with the blocked $160 billion Pfizer-Allergan Irish tax inversion.

Margrethe Vestager

EU Competition Commissioner, levied the largest corporate tax fine in

history on Apple Inc. on the 29 August 2016, for €13 billion (plus

interest) in Irish taxes avoided for the period 2004–2014.

The "closed-loop" element refers to the fact that the creation of the artificial internal intangible asset (which is critical to the BEPS

tool), can be done within the confines of the Irish-office of a global

accounting firm, and an Irish law firm, as well as the Irish Revenue Commissioners. No outside consent is needed to execute the BEPS tool (and use via Ireland's global tax-treaties), save for two situations:

- EU Commission State aid investigations, such as the EU illegal State aid case against Apple in Ireland for €13bn in Irish taxes avoided from 2004-2014;

- U.S. IRS investigation, such as Facebook's transfer of U.S. IP to Facebook Ireland, which was revalued much higher to create an IP BEPS tool.

Departure of U.S. and EU

The 2017-18 U.S. and EU Commission taxation initiatives, deliberately depart from the OECD BEPS Project,

and have their own explicit anti-IP BEPS tax regimes (as opposed to

waiting for the OECD). The U.S. GILTI and BEAT tax regimes are targeted

at U.S. multinationals in Ireland,

while the EU's Digital Services Tax is also directed at perceived

abuses by Ireland of the EU's transfer pricing systems (particularly in

regard to IP-based royalty payment charges).

For example, the new U.S. GILTI regime forces U.S. multinationals

in Ireland to pay an effective corporate tax rate of over 12%, even

with a full Irish IP BEPS tool (i.e. "single malt", whose effective

Irish tax rate is circa 0%). If they pay full Irish "headline" 12.5%

corporate tax rate, the effective corporate tax rate rises to over 14%.

This is compared to a new U.S. FDII tax regime of 13.125% for

U.S.-based IP, which reduces to circa 12% after the higher U.S. tax

relief.

U.S. multinationals like Pfizer announced in Q1 2018, a post-TCJA

global tax rate for 2019 of circa 17%, which is very similar to the

circa 16% expected by past U.S. multinational Irish tax inversions,

Eaton, Allergan, and Medtronic. This is the effect of Pfizer being

able to use the new U.S. 13.125% FDII regime, as well as the new U.S.

BEAT regime penalising non-U.S. multinationals (and past tax inversions) by taxing income leaving the U.S. to go to low-tax corporate tax havens like Ireland.

“Now that [U.S.] corporate tax reform has passed, the advantages of being an inverted company are less obvious”

— Jami Rubin, Goldman Sachs, March 2018,

Other jurisdictions, such as Japan, are also realising the extent to

which IP-based BEPS tools are being used to manage global corporate

taxes.

U.S. as BEPS winner

While the U.S. exchequer has traditionally been seen as the main loser to global corporate tax havens, the 15.5% repatriation rate of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 changes this calculus.

IP-heavy U.S. corporates are the main users of BEPS tools.

Studies show that as most other major economies run "territorial" tax

systems, their corporates did not need to profit shift. They could just

charge-out their IP to foreign markets from their home jurisdiction at

low tax rates (e.g. 5% in Germany for German corporates).

For example, there are no non-U.S./non-U.K. foreign corporates in

Ireland's top 50 firms by revenues, and only one by employees, German

retailer Lidl (whereas 14 of Ireland's top 20 firms are U.S.

multinationals). The U.K. firms are mainly pre § U.K. transformation.

Had U.S. multinationals not used IP-based BEPS tools in corporate

tax havens, and paid the circa 25% corporation tax (average OECD rate)

abroad, the U.S. exchequer would have only received an additional 10%

in tax (to bring the total effective U.S. worldwide tax rate to 35%).

However, post the TCJA,

the U.S. exchequer is now getting more tax, at the higher 15.5% rate,

and their U.S. corporations have avoided the 25% foreign taxes (and

therefore will have brought more capital back to the U.S. as result,

which will contribute to the U.S. economy in other ways).

This is at the expense of higher-tax Europe and Asian countries

(who received no taxes from U.S. corporations, as they used IP-based

BEPS tools from bases in corporate tax havens).

The U.S. did not sign the OECD's June 2017 MLI, as it felt that it had low exposure to profit shifting.

"The U.S. didn’t sign the groundbreaking tax treaty inked by 68 [later 70] countries in Paris June 7 [2017] because the U.S. tax treaty network has a low degree of exposure to base erosion and profit shifting issues", a U.S. Department of Treasury official said at a transfer pricing conference co-sponsored by Bloomberg BNA and Baker McKenzie in Washington

— Bloomberg BNA, "Treasury Official Explains Why U.S. Didn’t Sign OECD Super-Treaty", 8 June 2017

This beneficial effect of global tax havens to the U.S exchequer was

predicted by the ground-breaking Hines-Rice 1994 paper on tax havens.

It is undoubtedly true that some American business operations are drawn offshore by the lure of low tax rates in tax havens; nevertheless, the policies of tax havens may, on net, enhance the U.S. Treasury's ability to collect tax revenue from American corporations.

— James R Hines & Eric M Rice, Fiscal Paradise: Foreign tax havens and American business, 1994.

Corporate tax haven lists

Types of corporate tax haven lists

Before

2015, many lists are of general tax havens (i.e. individual and

corporate). Post 2015, quantitative studies (e.g. CORPNET and Gabriel Zucman), have highlighted the greater scale of corporate tax haven activity.

The OECD, who only list one jurisdiction in the world as a tax haven,

Trinidad and Tobago, note the scale of corporate tax haven activity. Note that the IMF list of offshore financial centres

("OFC") is often cited as the first list to include the main corporate

tax havens and the term OFC and corporate tax haven are often used

interchangeably.

- Intergovernmental lists. These lists can have a political dimension and have never named member states as tax havens:

- OECD lists. First produced in 2000, but has never contained one of the 35 OECD members, and currently only contains Trinidad and Tobago;

- European Union tax haven blacklist. First produced in 2017 but does not contain any EU-28 members, contained 17 blacklisted and 47 greylisted jurisdictions;

- IMF lists. First produced in 2000 but used the term offshore financial centre, which enabled them to list member states, but have become known as corporate tax havens.

- Non-governmental

lists. These are less prone to the political dimension and use a range

of qualitative and quantitative techniques:

- Tax Justice Network. One of the most quoted lists but focused on general tax havens; they created a separate Financial Secrecy Index in 2009;

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. Sponsor the "Offshore Shell Games" reports which are mainly corporate tax havens (see § ITEP Corporate tax havens);

- Oxfam. Now also producing separate annual lists on corporate tax havens from their corporate tax avoidance portal.

- Leading

academic lists. The first major academic studies were for all classes

of tax havens, however, later lists focus on corporate tax havens:

- James R. Hines Jr. Cited as the first coherent academic paper on tax havens; created the first list in 1994 of 41, which he expanded to 55 in 2010;

- Dharmapala. Built on Hines material and expanded the lists of general tax havens in 2006 and 2009;

- Gabriel Zucman. Current leading academic researcher into tax havens who explicitly uses the term corporate tax havens (see § Zucman Corporate tax havens).

- Other notable lists. Other noted and influential studies that produced lists are:

- CORPNET. Their 2017 quantitative analysis of Conduit and Sink OFCs explained the link between corporate tax havens and traditional tax havens;

- IMF Papers. An important 2018 paper highlighted a small group of major corporate tax haven that are 85% of all corporate haven activity;

- DIW Berlin. The respected German Institute for Economic Research have produced tax haven lists in 2017.

- U.S. Congress. The Government Accountability Office in 2008, and the Congressional Research Service in 2015, mostly focus on activities by U.S. corporations.

Ten major corporate tax havens

Regardless

of method, most corporate tax haven lists consistently repeat ten

jurisdictions (sometimes the Caribbean "triad" is one group), which

comprise:

- Four modern corporate tax havens (have non-zero "headline" tax rates; require "substance"/§ Employment tax; have broad tax treaty networks):

- Ireland;

- the Netherlands;

- United Kingdom (top 10 2017 global financial centre);

- Singapore (top 10 2017 global financial centre).

- Three

general corporate tax havens (offer some traditional tax-haven type

services; often have restricted bilateral tax treaties):

- Luxembourg (top 15 2017 global financial centre);

- Hong Kong (top 10 2017 global financial centre);