In quantum field theory, the Casimir effect (or Casimir force) is a physical force acting on the macroscopic boundaries of a confined space which arises from the quantum fluctuations of a field. The term Casimir pressure is sometimes used when it is described in units of force per unit area. It is named after the Dutch physicist Hendrik Casimir, who predicted the effect for electromagnetic systems in 1948.

In the same year Casimir, together with Dirk Polder, described a similar effect experienced by a neutral atom in the vicinity of a macroscopic interface which is called the Casimir–Polder force. Their result is a generalization of the London–van der Waals force and includes retardation due to the finite speed of light. The fundamental principles leading to the London–van der Waals force, the Casimir force, and the Casimir–Polder force can be formulated on the same footing.

In 1997 a direct experiment by Steven K. Lamoreaux quantitatively measured the Casimir force to be within 5% of the value predicted by the theory.

The Casimir effect can be understood by the idea that the presence of macroscopic material interfaces, such as electrical conductors and dielectrics, alter the vacuum expectation value of the energy of the second-quantized electromagnetic field. Since the value of this energy depends on the shapes and positions of the materials, the Casimir effect manifests itself as a force between such objects.

Any medium supporting oscillations has an analogue of the Casimir effect. For example, beads on a string as well as plates submerged in turbulent water or gas illustrate the Casimir force.

In modern theoretical physics, the Casimir effect plays an important role in the chiral bag model of the nucleon; in applied physics it is significant in some aspects of emerging microtechnologies and nanotechnologies.

Physical properties

The typical example is of two uncharged conductive plates in a vacuum, placed a few nanometers apart. In a classical description, the lack of an external field means that no field exists between the plates, and no force connects them. When this field is instead studied using the quantum electrodynamic vacuum, it is seen that the plates do affect the virtual photons that constitute the field, and generate a net force – either an attraction or a repulsion depending on the plates' specific arrangement. Although the Casimir effect can be expressed in terms of virtual particles interacting with the objects, it is best described and more easily calculated in terms of the zero-point energy of a quantized field in the intervening space between the objects. This force has been measured and is a striking example of an effect captured formally by second quantization.

The treatment of boundary conditions in these calculations is controversial. In fact, "Casimir's original goal was to compute the van der Waals force between polarizable molecules" of the conductive plates. Thus it can be interpreted without any reference to the zero-point energy (vacuum energy) of quantum fields.

Because the strength of the force falls off rapidly with distance, it is measurable only when the distance between the objects is small. This force becomes so strong that it becomes the dominant force between uncharged conductors at submicron scales. In fact, at separations of 10 nm – about 100 times the typical size of an atom – the Casimir effect produces the equivalent of about 1 atmosphere of pressure (the precise value depends on surface geometry and other factors).

History

Dutch physicists Hendrik Casimir and Dirk Polder at Philips Research Labs proposed the existence of a force between two polarizable atoms and between such an atom and a conducting plate in 1947; this special form is called the Casimir–Polder force. After a conversation with Niels Bohr, who suggested it had something to do with zero-point energy, Casimir alone formulated the theory predicting a force between neutral conducting plates in 1948. This latter phenomenon is called the Casimir effect.

Predictions of the force were later extended to finite-conductivity metals and dielectrics, while later calculations considered more general geometries. Experiments before 1997 observed the force qualitatively, and indirect validation of the predicted Casimir energy was made by measuring the thickness of liquid helium films. Finally, in 1997 Lamoreaux's direct experiment quantitatively measured the force to within 5% of the value predicted by the theory. Subsequent experiments approached an accuracy of a few percent.

Possible causes

Vacuum energy

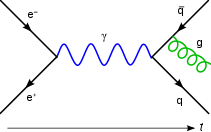

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

|

The causes of the Casimir effect are described by quantum field theory, which states that all of the various fundamental fields, such as the electromagnetic field, must be quantized at each and every point in space. In a simplified view, a "field" in physics may be envisioned as if space were filled with interconnected vibrating balls and springs, and the strength of the field can be visualized as the displacement of a ball from its rest position. Vibrations in this field propagate and are governed by the appropriate wave equation for the particular field in question. The second quantization of quantum field theory requires that each such ball-spring combination be quantized, that is, that the strength of the field be quantized at each point in space. At the most basic level, the field at each point in space is a simple harmonic oscillator, and its quantization places a quantum harmonic oscillator at each point. Excitations of the field correspond to the elementary particles of particle physics. However, even the vacuum has a vastly complex structure, so all calculations of quantum field theory must be made in relation to this model of the vacuum.

The vacuum has, implicitly, all of the properties that a particle may have: spin, polarization in the case of light, energy, and so on. On average, most of these properties cancel out: the vacuum is, after all, "empty" in this sense. One important exception is the vacuum energy or the vacuum expectation value of the energy. The quantization of a simple harmonic oscillator states that the lowest possible energy or zero-point energy that such an oscillator may have is

Summing over all possible oscillators at all points in space gives an infinite quantity. Since only differences in energy are physically measurable (with the notable exception of gravitation, which remains beyond the scope of quantum field theory), this infinity may be considered a feature of the mathematics rather than of the physics. This argument is the underpinning of the theory of renormalization. Dealing with infinite quantities in this way was a cause of widespread unease among quantum field theorists before the development in the 1970s of the renormalization group, a mathematical formalism for scale transformations that provides a natural basis for the process.

When the scope of the physics is widened to include gravity, the interpretation of this formally infinite quantity remains problematic. There is currently no compelling explanation as to why it should not result in a cosmological constant that is many orders of magnitude larger than observed. However, since we do not yet have any fully coherent quantum theory of gravity, there is likewise no compelling reason as to why it should instead actually result in the value of the cosmological constant that we observe.

The Casimir effect for fermions can be understood as the spectral asymmetry of the fermion operator (−1)F, where it is known as the Witten index.

Relativistic van der Waals force

Alternatively, a 2005 paper by Robert Jaffe of MIT states that "Casimir effects can be formulated and Casimir forces can be computed without reference to zero-point energies. They are relativistic, quantum forces between charges and currents. The Casimir force (per unit area) between parallel plates vanishes as alpha, the fine structure constant, goes to zero, and the standard result, which appears to be independent of alpha, corresponds to the alpha approaching infinity limit", and that "The Casimir force is simply the (relativistic, retarded) van der Waals force between the metal plates." Casimir and Polder's original paper used this method to derive the Casimir–Polder force. In 1978, Schwinger, DeRadd, and Milton published a similar derivation for the Casimir effect between two parallel plates. More recently, Nikolic proved from first principles of quantum electrodynamics that the Casimir force does not originate from the vacuum energy of the electromagnetic field, and explained in simple terms why the fundamental microscopic origin of Casimir force lies in van der Waals forces.

Effects

Casimir's observation was that the second-quantized quantum electromagnetic field, in the presence of bulk bodies such as metals or dielectrics, must obey the same boundary conditions that the classical electromagnetic field must obey. In particular, this affects the calculation of the vacuum energy in the presence of a conductor or dielectric.

Consider, for example, the calculation of the vacuum expectation value of the electromagnetic field inside a metal cavity, such as, for example, a radar cavity or a microwave waveguide. In this case, the correct way to find the zero-point energy of the field is to sum the energies of the standing waves of the cavity. To each and every possible standing wave corresponds an energy; say the energy of the nth standing wave is En. The vacuum expectation value of the energy of the electromagnetic field in the cavity is then

with the sum running over all possible values of n enumerating the standing waves. The factor of 1/2 is present because the zero-point energy of the nth mode is 1/2En, where En is the energy increment for the nth mode. (It is the same 1/2 as appears in the equation E = 1/2ħω.) Written in this way, this sum is clearly divergent; however, it can be used to create finite expressions.

In particular, one may ask how the zero-point energy depends on the shape s of the cavity. Each energy level En depends on the shape, and so one should write En(s) for the energy level, and ⟨E(s)⟩ for the vacuum expectation value. At this point comes an important observation: The force at point p on the wall of the cavity is equal to the change in the vacuum energy if the shape s of the wall is perturbed a little bit, say by δs, at p. That is, one has

This value is finite in many practical calculations.

Attraction between the plates can be easily understood by focusing on the one-dimensional situation. Suppose that a moveable conductive plate is positioned at a short distance a from one of two widely separated plates (distance l apart). With a ≪ l, the states within the slot of width a are highly constrained so that the energy E of any one mode is widely separated from that of the next. This is not the case in the large region l where there is a large number of states (about l/a) with energy evenly spaced between E and the next mode in the narrow slot, or in other words, all slightly larger than E. Now on shortening a by an amount da (which is negative), the mode in the narrow slot shrinks in wavelength and therefore increases in energy proportional to −da/a, whereas all the l/a states that lie in the large region lengthen and correspondingly decrease their energy by an amount proportional to −da/l (note the different denominator). The two effects nearly cancel, but the net change is slightly negative, because the energy of all the l/a modes in the large region are slightly larger than the single mode in the slot. Thus the force is attractive: it tends to make a slightly smaller, the plates drawing each other closer, across the thin slot.

Derivation of Casimir effect assuming zeta-regularization

In the original calculation done by Casimir, he considered the space between a pair of conducting metal plates at distance a apart. In this case, the standing waves are particularly easy to calculate, because the transverse component of the electric field and the normal component of the magnetic field must vanish on the surface of a conductor. Assuming the plates lie parallel to the xy-plane, the standing waves are

where ψ stands for the electric component of the electromagnetic field, and, for brevity, the polarization and the magnetic components are ignored here. Here, kx and ky are the wavenumbers in directions parallel to the plates, and

is the wavenumber perpendicular to the plates. Here, n is an integer, resulting from the requirement that ψ vanish on the metal plates. The frequency of this wave is

where c is the speed of light. The vacuum energy is then the sum over all possible excitation modes. Since the area of the plates is large, we may sum by integrating over two of the dimensions in k-space. The assumption of periodic boundary conditions yields,

where A is the area of the metal plates, and a factor of 2 is introduced for the two possible polarizations of the wave. This expression is clearly infinite, and to proceed with the calculation, it is convenient to introduce a regulator (discussed in greater detail below). The regulator will serve to make the expression finite, and in the end will be removed. The zeta-regulated version of the energy per unit-area of the plate is

In the end, the limit s → 0 is to be taken. Here s is just a complex number, not to be confused with the shape discussed previously. This integral sum is finite for s real and larger than 3. The sum has a pole at s = 3, but may be analytically continued to s = 0, where the expression is finite. The above expression simplifies to:

where polar coordinates q2 = kx2 + ky2 were introduced to turn the double integral into a single integral. The q in front is the Jacobian, and the 2π comes from the angular integration. The integral converges if Re(s) > 3, resulting in

The sum diverges at s in the neighborhood of zero, but if the damping of large-frequency excitations corresponding to analytic continuation of the Riemann zeta function to s = 0 is assumed to make sense physically in some way, then one has

But ζ(−3) = 1/120 and so one obtains

The analytic continuation has evidently lost an additive positive infinity, somehow exactly accounting for the zero-point energy (not included above) outside the slot between the plates, but which changes upon plate movement within a closed system. The Casimir force per unit area Fc/A for idealized, perfectly conducting plates with vacuum between them is

where

- ħ is the reduced Planck constant,

- c is the speed of light,

- a is the distance between the two plates

The force is negative, indicating that the force is attractive: by moving the two plates closer together, the energy is lowered. The presence of ħ shows that the Casimir force per unit area Fc/A is very small, and that furthermore, the force is inherently of quantum-mechanical origin.

By integrating the equation above it is possible to calculate the energy required to separate to infinity the two plates as:

where

- ħ is the reduced Planck constant,

- c is the speed of light,

- A is the area of one of the plates,

- a is the distance between the two plates

In Casimir's original derivation, a moveable conductive plate is positioned at a short distance a from one of two widely separated plates (distance L apart). The zero-point energy on both sides of the plate is considered. Instead of the above ad hoc analytic continuation assumption, non-convergent sums and integrals are computed using Euler–Maclaurin summation with a regularizing function (e.g., exponential regularization) not so anomalous as |ωn|−s in the above.

More recent theory

Casimir's analysis of idealized metal plates was generalized to arbitrary dielectric and realistic metal plates by Evgeny Lifshitz and his students. Using this approach, complications of the bounding surfaces, such as the modifications to the Casimir force due to finite conductivity, can be calculated numerically using the tabulated complex dielectric functions of the bounding materials. Lifshitz's theory for two metal plates reduces to Casimir's idealized 1/a4 force law for large separations a much greater than the skin depth of the metal, and conversely reduces to the 1/a3 force law of the London dispersion force (with a coefficient called a Hamaker constant) for small a, with a more complicated dependence on a for intermediate separations determined by the dispersion of the materials.

Lifshitz's result was subsequently generalized to arbitrary multilayer planar geometries as well as to anisotropic and magnetic materials, but for several decades the calculation of Casimir forces for non-planar geometries remained limited to a few idealized cases admitting analytical solutions. For example, the force in the experimental sphere–plate geometry was computed with an approximation (due to Derjaguin) that the sphere radius R is much larger than the separation a, in which case the nearby surfaces are nearly parallel and the parallel-plate result can be adapted to obtain an approximate R/a3 force (neglecting both skin-depth and higher-order curvature effects). However, in the 2010s a number of authors developed and demonstrated a variety of numerical techniques, in many cases adapted from classical computational electromagnetics, that are capable of accurately calculating Casimir forces for arbitrary geometries and materials, from simple finite-size effects of finite plates to more complicated phenomena arising for patterned surfaces or objects of various shapes.

Measurement

One of the first experimental tests was conducted by Marcus Sparnaay at Philips in Eindhoven (Netherlands), in 1958, in a delicate and difficult experiment with parallel plates, obtaining results not in contradiction with the Casimir theory, but with large experimental errors.

The Casimir effect was measured more accurately in 1997 by Steve K. Lamoreaux of Los Alamos National Laboratory, and by Umar Mohideen and Anushree Roy of the University of California, Riverside. In practice, rather than using two parallel plates, which would require phenomenally accurate alignment to ensure they were parallel, the experiments use one plate that is flat and another plate that is a part of a sphere with a very large radius.

In 2001, a group (Giacomo Bressi, Gianni Carugno, Roberto Onofrio and Giuseppe Ruoso) at the University of Padua (Italy) finally succeeded in measuring the Casimir force between parallel plates using microresonators.[37] Numerous variations of these experiments are summarized in the 2009 review by Klimchitskaya.[38]

In 2013, a conglomerate of scientists from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, University of Florida, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory demonstrated a compact integrated silicon chip that can measure the Casimir force. The integrated chip defined by electron-beam lithography does not need extra alignment, making it an ideal platform for measuring Casimir force between complex geometries. In 2017 and 2021, the same group from Hong Kong University of Science and Technology demonstrated the non-monotonic Casimir force and distance-independent Casimir force, respectively, using this on-chip platform.

Regularization

In order to be able to perform calculations in the general case, it is convenient to introduce a regulator in the summations. This is an artificial device, used to make the sums finite so that they can be more easily manipulated, followed by the taking of a limit so as to remove the regulator.

The heat kernel or exponentially regulated sum is

where the limit t → 0+ is taken in the end. The divergence of the sum is typically manifested as

for three-dimensional cavities. The infinite part of the sum is associated with the bulk constant C which does not depend on the shape of the cavity. The interesting part of the sum is the finite part, which is shape-dependent. The Gaussian regulator

is better suited to numerical calculations because of its superior convergence properties, but is more difficult to use in theoretical calculations. Other, suitably smooth, regulators may be used as well. The zeta function regulator

is completely unsuited for numerical calculations, but is quite useful in theoretical calculations. In particular, divergences show up as poles in the complex s plane, with the bulk divergence at s = 4. This sum may be analytically continued past this pole, to obtain a finite part at s = 0.

Not every cavity configuration necessarily leads to a finite part (the lack of a pole at s = 0) or shape-independent infinite parts. In this case, it should be understood that additional physics has to be taken into account. In particular, at extremely large frequencies (above the plasma frequency), metals become transparent to photons (such as X-rays), and dielectrics show a frequency-dependent cutoff as well. This frequency dependence acts as a natural regulator. There are a variety of bulk effects in solid state physics, mathematically very similar to the Casimir effect, where the cutoff frequency comes into explicit play to keep expressions finite. (These are discussed in greater detail in Landau and Lifshitz, "Theory of Continuous Media".)

Generalities

The Casimir effect can also be computed using the mathematical mechanisms of functional integrals of quantum field theory, although such calculations are considerably more abstract, and thus difficult to comprehend. In addition, they can be carried out only for the simplest of geometries. However, the formalism of quantum field theory makes it clear that the vacuum expectation value summations are in a certain sense summations over so-called "virtual particles".

More interesting is the understanding that the sums over the energies of standing waves should be formally understood as sums over the eigenvalues of a Hamiltonian. This allows atomic and molecular effects, such as the Van der Waals force, to be understood as a variation on the theme of the Casimir effect. Thus one considers the Hamiltonian of a system as a function of the arrangement of objects, such as atoms, in configuration space. The change in the zero-point energy as a function of changes of the configuration can be understood to result in forces acting between the objects.

In the chiral bag model of the nucleon, the Casimir energy plays an important role in showing the mass of the nucleon is independent of the bag radius. In addition, the spectral asymmetry is interpreted as a non-zero vacuum expectation value of the baryon number, cancelling the topological winding number of the pion field surrounding the nucleon.

A "pseudo-Casimir" effect can be found in liquid crystal systems, where the boundary conditions imposed through anchoring by rigid walls give rise to a long-range force, analogous to the force that arises between conducting plates.

Dynamical Casimir effect

The dynamical Casimir effect is the production of particles and energy from an accelerated moving mirror. This reaction was predicted by certain numerical solutions to quantum mechanics equations made in the 1970s. In May 2011 an announcement was made by researchers at the Chalmers University of Technology, in Gothenburg, Sweden, of the detection of the dynamical Casimir effect. In their experiment, microwave photons were generated out of the vacuum in a superconducting microwave resonator. These researchers used a modified SQUID to change the effective length of the resonator in time, mimicking a mirror moving at the required relativistic velocity. If confirmed this would be the first experimental verification of the dynamical Casimir effect. In March 2013 an article appeared on the PNAS scientific journal describing an experiment that demonstrated the dynamical Casimir effect in a Josephson metamaterial. In July 2019 an article was published describing an experiment providing evidence of optical dynamical Casimir effect in a dispersion-oscillating fibre. In 2020, Frank Wilczek et al., proposed a resolution to the information loss paradox associated with the moving mirror model of the dynamical Casimir effect. Constructed within the framework of quantum field theory in curved spacetime, the dynamical Casimir effect (moving mirror) has been used to help understand the Unruh effect.

Repulsive forces

There are few instances wherein the Casimir effect can give rise to repulsive forces between uncharged objects. Evgeny Lifshitz showed (theoretically) that in certain circumstances (most commonly involving liquids), repulsive forces can arise. This has sparked interest in applications of the Casimir effect toward the development of levitating devices. An experimental demonstration of the Casimir-based repulsion predicted by Lifshitz was carried out by Munday et al. who described it as "quantum levitation". Other scientists have also suggested the use of gain media to achieve a similar levitation effect, though this is controversial because these materials seem to violate fundamental causality constraints and the requirement of thermodynamic equilibrium (Kramers–Kronig relations). Casimir and Casimir–Polder repulsion can in fact occur for sufficiently anisotropic electrical bodies; for a review of the issues involved with repulsion see Milton et al. A notable recent development on repulsive Casimir forces relies on using chiral materials. Q.-D. Jiang at Stockholm University and Nobel Laureate Frank Wilczek at MIT show that chiral "lubricant" can generate repulsive, enhanced, and tunable Casimir interactions.

Timothy Boyer showed in his work published in 1968 that a conductor with spherical symmetry will also show this repulsive force, and the result is independent of radius. Further work shows that the repulsive force can be generated with materials of carefully chosen dielectrics.

Speculative applications

It has been suggested that the Casimir forces have application in nanotechnology, in particular silicon integrated circuit technology based micro- and nanoelectromechanical systems, and so-called Casimir oscillators.

In 1995 and 1998 Maclay et al. published the first models of a microelectromechanical system (MEMS) with Casimir forces. While not exploiting the Casimir force for useful work, the papers drew attention from the MEMS community due to the revelation that Casimir effect needs to be considered as a vital factor in the future design of MEMS. In particular, Casimir effect might be the critical factor in the stiction failure of MEMS.

In 2001, Capasso et al. showed how the force can be used to control the mechanical motion of a MEMS device, The researchers suspended a polysilicon plate from a torsional rod – a twisting horizontal bar just a few microns in diameter. When they brought a metallized sphere close up to the plate, the attractive Casimir force between the two objects made the plate rotate. They also studied the dynamical behaviour of the MEMS device by making the plate oscillate. The Casimir force reduced the rate of oscillation and led to nonlinear phenomena, such as hysteresis and bistability in the frequency response of the oscillator. According to the team, the system's behaviour agreed well with theoretical calculations.

The Casimir effect shows that quantum field theory allows the energy density in very small regions of space to be negative relative to the ordinary vacuum energy, and the energy densities cannot be arbitrarily negative as the theory breaks down at atomic distances. Such prominent physicists such as Stephen Hawking and Kip Thorne, have speculated that such effects might make it possible to stabilize a traversable wormhole.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}U_{E}(a)&=\int F(a)\,da=\int -\hbar c\pi ^{2}{\frac {A}{240a^{4}}}\,da\\[4pt]&=\hbar c\pi ^{2}{\frac {A}{720a^{3}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/19ee5b5fe6831ed1cf8fa9069c471b7e45e62b3e)