Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary mental states (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips") and a perceived "expansion of consciousness". Also referred to as classic hallucinogens or serotonergic hallucinogens, the term psychedelic is sometimes used more broadly to include various types of hallucinogens, such as those which are atypical or adjacent to psychedelia like salvia and MDMA, respectively.

Classic psychedelics generally cause specific psychological, visual, and auditory changes, and oftentimes a substantially altered state of consciousness. They have had the largest influence on science and culture, and include mescaline, LSD, psilocybin, and DMT.

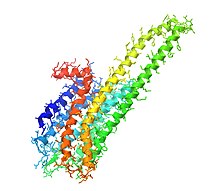

Most psychedelic drugs fall into one of the three families of chemical compounds: tryptamines, phenethylamines, or lysergamides (LSD is considered both a tryptamine and lysergamide). They act via serotonin 2A receptor agonism. When compounds bind to serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, they modulate the activity of key circuits in the brain involved with sensory perception and cognition. However, the exact nature of how psychedelics induce changes in perception and cognition via the 5-HT2A receptor is still unknown. The psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as those experienced in meditation, mystical experiences, and near-death experiences, which also appear to be partially underpinned by altered default mode network activity. The phenomenon of ego death is often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.

Many psychedelic drugs are illegal to possess without lawful authorisation, exemption or license worldwide under the UN conventions, with occasional exceptions for religious use or research contexts. Despite these controls, recreational use of psychedelics is common. Legal barriers have made the scientific study of psychedelics more difficult. Research has been conducted, however, and studies show that psychedelics are physiologically safe and rarely lead to addiction. Studies conducted using psilocybin in a psychotherapeutic setting reveal that psychedelic drugs may assist with treating depression, alcohol addiction, and nicotine addiction. Although further research is needed, existing results suggest that psychedelics could be effective treatments for certain forms of psychopathology. A 2022 survey found that 28% of Americans had used a psychedelic at some point in their life.

Etymology and nomenclature

The term psychedelic was coined by the psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond during written correspondence with author Aldous Huxley (written in a rhyme: “To fathom Hell or soar angelic/Just take a pinch of psychedelic.”) and presented to the New York Academy of Sciences by Osmond in 1957. It is irregularly derived from the Greek words ψυχή (psychḗ, meaning 'mind, soul') and δηλείν (dēleín, meaning 'to manifest'), with the intended meaning "mind manifesting" or alternatively "soul manifesting", and the implication that psychedelics can reveal unused potentials of the human mind. The term was loathed by American ethnobotanist Richard Schultes but championed by American psychologist Timothy Leary.

Aldous Huxley had suggested his own coinage phanerothyme (Greek phaneroein- "to make manifest or visible" and Greek thymos "soul", thus "to reveal the soul") to Osmond in 1956. Recently, the term entheogen (meaning "that which produces the divine within") has come into use to denote the use of psychedelic drugs, as well as various other types of psychoactive substances, in a religious, spiritual, and mystical context.

In 2004, David E. Nichols wrote the following about the nomenclature used for psychedelic drugs:

Many different names have been proposed over the years for this drug class. The famous German toxicologist Louis Lewin used the name phantastica earlier in this century, and as we shall see later, such a descriptor is not so farfetched. The most popular names—hallucinogen, psychotomimetic, and psychedelic ("mind manifesting")—have often been used interchangeably. Hallucinogen is now, however, the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the term psychedelic is still the most popular and has held sway for nearly four decades. Most recently, there has been a movement in nonscientific circles to recognize the ability of these substances to provoke mystical experiences and evoke feelings of spiritual significance. Thus, the term entheogen, derived from the Greek word entheos, which means "god within", was introduced by Ruck et al. and has seen increasing use. This term suggests that these substances reveal or allow a connection to the "divine within". Although it seems unlikely that this name will ever be accepted in formal scientific circles, its use has dramatically increased in the popular media and on internet sites. Indeed, in much of the counterculture that uses these substances, entheogen has replaced psychedelic as the name of choice and we may expect to see this trend continue.

Robin Carhart-Harris and Guy Goodwin write that the term psychedelic is preferable to hallucinogen for describing classical psychedelics because of the term hallucinogen's "arguably misleading emphasis on these compounds' hallucinogenic properties."

While the term psychedelic is most commonly used to refer only to serotonergic hallucinogens, it is sometimes used for a much broader range of drugs, including empathogen–entactogens, dissociatives, and atypical hallucinogens/psychoactives such as Amanita muscaria, Cannabis sativa, Nymphaea nouchali and Salvia divinorum. Thus, the term serotonergic psychedelic is sometimes used for the narrower class. It is important to check the definition of a given source. This article uses the more common, narrower definition of psychedelic.

Examples

- 2C-B (2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine) is a substituted phenethylamine first synthesised in 1974 by Alexander Shulgin. 2C-B is both a psychedelic and a mild entactogen, with its psychedelic effects increasing and its entactogenic effects decreasing with dosage. 2C-B is the most well known compound in the 2C family, their general structure being discovered as a result of modifying the structure of mescaline.

- DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is an indole alkaloid found in various species of plants. Traditionally it is consumed by tribes in South America in the form of ayahuasca. A brew is used that consists of DMT-containing plants as well as plants containing MAOIs, specifically harmaline, which allows DMT to be consumed orally without being rendered inactive by monoamine oxidase enzymes in the digestive system. A pharmaceutical version of ayahuasca is called pharmahuasca. In the Western world DMT is more commonly consumed via the vaporisation of freebase DMT. Whereas Ayahuasca typically lasts for several hours, inhalation has an onset measured in seconds and has effects measured in minutes, being significantly more intense. Particularly in vaporised form, DMT has the ability to cause users to enter a hallucinatory realm fully detached from reality, being typically characterised by hyperbolic geometry, and described as defying visual or verbal description. Users have also reported encountering and communicating with entitites within this hallucinatory state. DMT is the archetypal substituted tryptamine, being the structural scaffold of psilocybin and – to a lesser extent – the lysergamides.

- LSD (Lysergic acid diethylamide) is a derivative of lysergic acid, which is obtained from the hydrolysis of ergotamine. Ergotamine is an alkaloid found in the fungus Claviceps purpurea, which primarily infects rye. LSD is both the prototypical psychedelic and the prototypical lysergamide. As a lysergamide, LSD contains both a tryptamine and phenethylamine group within its structure. As a result of containing a phenethylamine group LSD agonises dopamine receptors as well as serotonin receptors, making it more energetic in effect in contrast to the more sedating effects of psilocin, which is not a dopamine agonist.

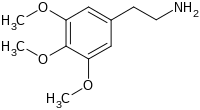

- Mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a phenethylamine alkaloid found in various species of cacti, the best-known of these being peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi, syn. Echinopsis pachanoi). Mescaline has effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin, albeit with a greater emphasis on colors and patterns. Ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.

- Psilocin (4-HO-DMT) is the dephosphorylated active metabolite of the indole alkaloid psilocybin and a substituted tryptamine, which is produced in over 200 species of fungi. Of the Classical psychedelics psilocybin has attracted the greatest academic interest regarding its ability to manifest mystical experiences, although all psychedelics are capable of doing so to variable degrees. O-Acetylpsilocin (4-AcO-DMT) is an acetylated analog of psilocin. Additionally, replacement of a methyl group at the dimethylated nitrogen with an isopropyl or ethyl group yields 4-HO-MIPT and 4-HO-MET, respectively.

Uses

Traditional

A number of frequently mentioned or traditional psychedelics such as Ayahuasca (which contains DMT), San Pedro, Peyote, and Peruvian torch (which all contain mescaline), Psilocybe mushrooms (which contain psilocin/psilocybin) and Tabernanthe iboga (which contains the unique psychedelic ibogaine) all have a long and extensive history of spiritual, shamanic and traditional usage by indigenous peoples in various world regions, particularly in Latin America, but also Gabon, Africa in the case of iboga. Different countries and/or regions have come to be associated with traditional or spiritual use of particular psychedelics, such as the ancient and entheogenic use of psilocybe mushrooms by the native Mazatec people of Oaxaca, Mexico or the use of the ayahuasca brew in the Amazon basin, particularly in Peru for spiritual and physical healing as well as for religious festivals. Peyote has also been used for several thousand years in the Rio Grande Valley in North America by native tribes as an entheogen. In the Andean region of South America, the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi, syn. Echinopsis pachanoi) has a long history of use, possibly as a traditional medicine. Archaeological studies have found evidence of use going back two thousand years, to Moche culture, Nazca culture, and Chavín culture. Although authorities of the Roman Catholic church attempted to suppress its use after the Spanish conquest, this failed, as shown by the Christian element in the common name "San Pedro cactus" – Saint Peter cactus. The name has its origin in the belief that just as St Peter holds the keys to heaven, the effects of the cactus allow users "to reach heaven while still on earth." In 2022, the Peruvian Ministry of Culture declared the traditional use of San Pedro cactus in northern Peru as cultural heritage.

Although people of Western culture have tended to use psychedelics for either psychotherapeutic or recreational reasons, most indigenous cultures, particularly in South America, have seemingly tended to use psychedelics for more supernatural reasons such as divination. This can often be related to "healing" or health as well but typically in the context of finding out what is wrong with the individual, such as using psychedelic states to "identify" a disease and/or its cause, locate lost objects, and identify a victim or even perpetrator of sorcery. In some cultures and regions, even psychedelics themselves, such as ayahuasca and the psychedelic lichen of eastern Ecuador (Dictyonema huaorani) that supposedly contains both 5-MeO-DMT and psilocybin, have also been used by witches and sorcerers to conduct their malicious magic, similarly to nightshade deliriants like brugmansia and latua.

Psychedelic therapy

Psychedelic therapy (or psychedelic-assisted therapy) is the proposed use of psychedelic drugs to treat mental disorders. As of 2021, psychedelic drugs are controlled substances in most countries and psychedelic therapy is not legally available outside clinical trials, with some exceptions.

The procedure for psychedelic therapy differs from that of therapies using conventional psychiatric medications. While conventional medications are usually taken without supervision at least once daily, in contemporary psychedelic therapy the drug is administered in a single session (or sometimes up to three sessions) in a therapeutic context. The therapeutic team prepares the patient for the experience beforehand and helps them integrate insights from the drug experience afterwards. After ingesting the drug, the patient normally wears eyeshades and listens to music to facilitate focus on the psychedelic experience, with the therapeutic team interrupting only to provide reassurance if adverse effects such as anxiety or disorientation arise.

As of 2022, the body of high-quality evidence on psychedelic therapy remains relatively small and more, larger studies are needed to reliably show the effectiveness and safety of psychedelic therapy's various forms and applications. On the basis of favorable early results, ongoing research is examining proposed psychedelic therapies for conditions including major depressive disorder, and anxiety and depression linked to terminal illness. The United States Food and Drug Administration has granted "breakthrough therapy" status, which expedites the assessment of promising drug therapies for potential approval, to psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder.

It has been proposed that psychedelics used for therapeutic purposes may act as active "super placebos".

Recreational

Recreational use of psychedelics has been common since the psychedelic era of the mid-1960s and continues to play a role in various festivals and events, including Burning Man. A survey published in 2013 found that 13.4% of American adults had used a psychedelic.

A June 2024 report by the RAND Corporation suggests psilocybin mushrooms may be the most prevalent psychedelic drug among adults in the United States. The RAND national survey indicated that 3.1% of U.S. adults reported using psilocybin in the past year. Roughly 12% of respondents acknowledged lifetime use of psilocybin, while a similar percentage reported having used LSD at some point in their lives. MDMA, also known as ecstasy, showed a lower prevalence of use at 7.6%. Notably, less than 1% of U.S. adults reported using any psychedelic drugs within the past month.

Microdosing

Psychedelic microdosing is the practice of using sub-threshold doses (microdoses) of psychedelics in an attempt to improve creativity, boost physical energy level, emotional balance, increase performance on problems-solving tasks and to treat anxiety, depression and addiction. The practice of microdosing has become more widespread in the 21st century with more people claiming long-term benefits from the practice.

A 2022 study recognized signatures of psilocybin microdosing in natural language and concluded that low amount of psychedelics have potential for application, and ecological observation of microdosing schedules.

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Most serotonergic psychedelics act as non-selective agonists of serotonin receptors, including of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, but often also of other serotonin receptors, such as the serotonin 5-HT1 receptors. They are thought to mediate their hallucinogenic effects specifically by activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Psychedelics, such as the tryptamines psilocin, DMT, and 5-MeO-DMT, the phenethylamines mescaline, DOM, and 2C-B, and ergolines and lysergamides like LSD, all act as agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Some psychedelics, such as phenethylamines like DOM and 2C-B, show high selectivity for the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors over other serotonin receptors. There is a very strong correlation between 5-HT2A receptor affinity and human hallucinogenic potency. In addition, the intensity of hallucinogenic effects in humans is directly correlated with the level of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor occupancy as measured with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor blockade with drugs like the semi-selective ketanserin and the non-selective risperidone can abolish the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics in humans. However, studies with more selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like pimavanserin, are still needed.

In animals, potency for stimulus generalization to the psychedelic DOM in drug discrimination tests is strongly correlated with serotonin 5-HT2A receptor affinity. Non-selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like ketanserin and pirenperone, and selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like volinanserin (MDL-100907), abolish the stimulus generalization of psychedelics in drug discrimination tests. Conversely, serotonin 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists are ineffective. The potencies of serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists in blocking psychedelic substitution are strongly correlated with their serotonin 5-HT2A receptor affinities. Highly selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists have recently been developed and show stimulus generalization to psychedelics, whereas selective serotonin 5-HT2C receptor agonists do not do so. The head-twitch response (HTR) is induced by serotonergic psychedelics and is a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects in animals. The HTR is invariably induced by serotonergic psychedelics, is blocked by selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, and is abolished in serotonin 5-HT2A receptor knockout mice. In addition, there is a strong correlation between hallucinogenic potency in humans and potency in the HTR assay. Moreover, the HTR paradigm is one of the only animal tests that can distinguish between hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists and non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, such as lisuride. In accordance with the preceding animal and human findings, it has been said that the evidence that the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor mediates the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics is overwhelming.

The serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activates several downstream signaling pathways. These include the Gq, β-arrestin2, and other pathways. Activation of both the Gq and β-arrestin2 pathways have been implicated in mediating the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics. However, subsequently, activation of the Gq pathway and not β-arrestin2 has been implicated. Interestingly, Gq signaling appeared to mediate hallucinogenic-like effects, whereas β-arrestin2 mediated receptor downregulation and tachyphylaxis. The lack of psychedelic effects with non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists may be due to partial agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor with efficacy insufficient to produce psychedelic effects or may be due to biased agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor. There appears to be a threshold level of Gq activation (in terms of intrinsic activity, with Emax >70%) required for production of hallucinogenic effects. Full agonists and partial agonists above this threshold are psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonists, whereas partial agonists below this threshold, such as lisuride, 2-bromo-LSD, 6-fluoro-DET, 6-MeO-DMT, and Ariadne, are non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists. In addition, biased agonists that activate β-arrestin2 signaling but not Gq signaling, such as ITI-1549, IHCH-7086, and 25N-N1-Nap, are non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists.

The hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics may be critically mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Layer V pyramidal neurons in this area are especially discussed. Activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the mPFC results in marked excitatory and inhibitory effects as well as increased release of glutamate and GABA. Direct injection of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists into the mPFC produces the HTR. Drugs that suppress glutamatergic activity in the mPFC, including AMPA receptor antagonists, metabotropic glutamate mGlu2/3 receptor agonists, μ-opioid receptor agonists, and adenosine A1 receptor agonists, block or suppress many of the neurochemical and behavioral effects of serotonergic psychedelics, including the HTR. Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptors are primarily expressed as presynaptic autoreceptors and have inhibitory effects on glutamate release. Serotonergic psychedelics have been found to produce frontal cortex hyperactivity in humans in PET and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging studies. The PFC projects to many other cortical and subcortical brain areas, such as the locus coeruleus, nucleus accumbens, and amygdala, among others, and activation of the PFC by serotonergic psychedelics may thereby indirectly modulate these areas. In addition to the PFC, there is moderate to high expression of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the primary visual cortex (V1), as well as expression of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in other visual areas, and activation of these receptors may contribute to or mediate the visual effects of serotonergic psychedelics. Serotonergic psychedelics also directly or indirectly modulate a variety of other brain areas, like the claustrum, and this may be involved in their effects as well.

Serotonin, as well as drugs that increase serotonin levels, like the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin releasing agents, are non-hallucinogenic in humans despite increasing activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Serotonin is a hydrophilic molecule which cannot easily cross biological membranes without active transport, and the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is usually expressed as a cell surface receptor that is readily accessible to extracellular serotonin. The HTR, a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects, appears to be mediated by activation of intracellularly expressed serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in a population of mPFC neurons that do not also express the serotonin transporter (SERT) and hence cannot be activated by serotonin. In contrast to serotonin, serotonergic psychedelics are more lipophilic than serotonin and are able to readily enter these neurons and activate the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors within them. Artificial expression of the SERT in this population of neurons in animals resulted in a serotonin releasing agent that doesn't normally produce the HTR being able to do so. Although serotonin itself is non-hallucinogenic, at very high concentrations achieved pharmacologically (e.g., injected into the brain or with massive doses of 5-HTP) it can produce psychedelic-like effects in animals by being metabolized by indolethylamine N-methyltransferase (INMT) into more lipophilic N-methylated tryptamines like N-methylserotonin and bufotenin (N,N-dimethylserotonin).

In addition to their hallucinogenic effects, serotonergic psychedelics may also produce a variety of other effects, including psychoplastogenic (i.e., neuroplasticity-enhancing), antidepressant, anxiolytic, empathy-enhancing or prosocial effects, anti-obsessional, anti-addictive, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, analgesic effects, and/or antimigraine effects. While psychedelics themselves are also being clinically evaluated for these potential therapeutic benefits, non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, which are often analogues of serotonergic psychedelics, have been developed and are being studied for potential use in medicine in an attempt to provide some such benefits without hallucinogenic effects.

Although the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics are thought to be mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation, interactions with other receptors, such as the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors among many others, may additionally contribute to and modulate their effects. Interestingly, some psychedelics, such as LSD and psilocybin, have been claimed to act as positive allosteric modulators of the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), one of the signaling receptors of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). However, despite this apparent TrkB potentiation, the psychoplastogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics, including dendritogenesis, spinogenesis, and synaptogenesis, appear to be mediated by activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, whereas psychedelics do not generally stimulate neurogenesis.

Chemical families

The three major chemical groups of serotonergic psychedelics include the tryptamines, phenethylamines, and lysergamides, which each have different profiles of pharmacological activity.

Tryptamines

Tryptamines are derivatives of tryptamine and are structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitter serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT). Many tryptamines act as non-selective serotonin receptor agonists, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor. Some tryptamines also act as monoamine releasing agents, including of serotonin, norepinephrine, and/or dopamine. Examples of psychedelic tryptamines include tryptamine, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 5-MeO-DMT, psilocin, psilocybin, bufotenin, 5-MeO-DiPT, 5-MeO-MiPT, α-methyltryptamine (αMT), and 5-MeO-αMT, among many others.

Phenethylamines

Phenethylamines, as well as amphetamines (α-methylphenethylamines), are derivatives of β-phenethylamine and are structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Some phenethylamines and amphetamines, particularly those with methoxy and other substitions on the phenyl ring, are potent serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonists, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, and can produce psychedelic effects. In contrast to phenethylamines and amphetamines generally, most psychedelic phenethylamines are not monoamine releasing agents. Examples of psychedelic phenethylamines and amphetamines include mescaline, the 2C drugs like 2C-B, 2C-D, 2C-E, and 2C-I, the DOx drugs like DOB, DOI, and DOM, certain MDxx drugs like MDA and MDMA (weak psychedelics), and the NBOMe (25x-NBx) drugs like 25C-NBOMe and 25I-NBOMe.

Lysergamides

Lysergamides are ergoline derivatives related to the ergot alkaloids. They are notable in containing both tryptamine and phenethylamine within their chemical structures. As such, ergolines and lysergamides may be considered structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitters. Many ergolines and lysergamides act as highly promiscuous ligands of monoamine receptors, including of serotonin, dopamine, and adrenergic receptors. Some lysergamides are efficacious serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists and thereby produce psychedelic effects. Examples of psychedelic lysergamides include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), lysergic acid amide (LSA), 1P-LSD, ALD-52, ergonovine (ergometrine), and methylergometrine (methylergonovine), among others.

Psychedelic experiences

Although several attempts have been made, starting in the 19th and 20th centuries, to define common phenomenological structures of the effects produced by classic psychedelics, a universally accepted taxonomy does not yet exist. At lower doses, features of psychedelic experiences include sensory alterations, such as the warping of surfaces, shape suggestibility, pareidolia and color variations. Users often report intense colors that they have not previously experienced, and repetitive geometric shapes or form constants are common as well. Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental alterations of sensory (notably visual) perception, such as synesthesia or the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions. Tryptamines are well documented to cause classic psychedelic states, such as increased empathy, visual distortions (drifting, morphing, breathing, melting of various surfaces and objects), auditory hallucinations, ego dissolution or ego death with high enough dose, mystical, transpersonal and spiritual experiences, autonomous "entity" encounters, time distortion, closed eye hallucinations and complete detachment from reality with a high enough dose. Luis Luna describes psychedelic experiences as having a distinctly gnosis-like quality, and says that they offer "learning experiences that elevate consciousness and can make a profound contribution to personal development." Czech psychiatrist Stanislav Grof studied the effects of psychedelics like LSD early in his career and said of the experience, that it commonly includes "complex revelatory insights into the nature of existence… typically accompanied by a sense of certainty that this knowledge is ultimately more relevant and 'real' than the perceptions and beliefs we share in everyday life." Traditionally, the standard model for the subjective phenomenological effects of psychedelics has typically been based on LSD, with anything that is considered "psychedelic" evidently being compared to it and its specific effects.

During a speech on his 100th birthday, the inventor of LSD, Albert Hofmann said of the drug: "It gave me an inner joy, an open mindedness, a gratefulness, open eyes and an internal sensitivity for the miracles of creation... I think that in human evolution it has never been as necessary to have this substance LSD. It is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be." With certain psychedelics and experiences, a user may also experience an "afterglow" of improved mood or perceived mental state for days or even weeks after ingestion in some cases. In 1898, the English writer and intellectual Havelock Ellis reported a heightened perceptual sensitivity to "the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and color" for a prolonged period of time after his exposure to mescaline. Good trips are reportedly deeply pleasurable, and typically involve intense joy or euphoria, a greater appreciation for life, reduced anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and a sense of belonging or interconnectedness with the universe. Negative experiences, colloquially known as "bad trips," evoke an array of dark emotions, such as irrational fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, dread, distrustfulness, hopelessness, and even suicidal ideation. While it is impossible to predict when a bad trip will occur, one's mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, social setting, and other factors can be controlled (colloquially referred to as "set and setting") to minimize the risk of a bad trip. The concept of "set and setting" also generally appears to be more applicable to psychedelics than to other types of hallucinogens such as deliriants, hypnotics and dissociative anesthetics.

Classic psychedelics are considered to be those found in nature like psilocybin, DMT, mescaline, and LSD which is derived from naturally occurring ergotamine, and non-classic psychedelics are considered to be newer analogs and derivatives of pharmacophore lysergamides, tryptamine, and phenethylamine structures like 2C-B. Many of these psychedelics cause remarkably similar effects, despite their different chemical structure. However, many users report that the three major families have subjectively different qualities in the "feel" of the experience, which are difficult to describe. Some compounds, such as 2C-B, have extremely tight "dose curves", meaning the difference in dose between a non-event and an overwhelming disconnection from reality can be very slight. There can also be very substantial differences between the drugs; for instance, 5-MeO-DMT rarely produces the visual effects typical of other psychedelics.

Potential adverse effects

Despite the contrary perception of much of the public, psychedelic drugs are not addictive and are physiologically safe. As of 2016, there have been no known deaths due to overdose of LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline.

Risks do exist during an unsupervised psychedelic experience, however; Ira Byock wrote in 2018 in the Journal of Palliative Medicine that psilocybin is safe when administered to a properly screened patient and supervised by a qualified professional with appropriate set and setting. However, he called for an "abundance of caution" because in the absence of these conditions a range of negative reactions is possible, including "fear, a prolonged sense of dread, or full panic." He notes that driving or even walking in public can be dangerous during a psychedelic experience because of impaired hand-eye coordination and fine motor control. In some cases, individuals taking psychedelics have performed dangerous or fatal acts because they believed they possessed superhuman powers.

Psilocybin-induced states of mind share features with states experienced in psychosis, and while a causal relationship between psilocybin and the onset of psychosis has not been established as of 2011, researchers have called for investigation of the relationship. Many of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence, with the majority of reported adverse effects not being observed in a regulated and/or medical context. A population study on associations between psychedelic use and mental illness published in 2013 found no evidence that psychedelic use was associated with increased prevalence of any mental illness. In any case, induction of psychosis has been associated with psychedelics in small percentages of individuals, and the rates appear to be higher in people with schizophrenia.

Using psychedelics poses certain risks of re-experiencing of the drug's effects, including flashbacks and hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD). These non-psychotic effects are poorly studied, but the permanent symptoms (also called "endless trip") are considered to be rare.

Serotonin syndrome can be caused by combining psychedelics with other serotonergic drugs, including certain antidepressants, opioids, CNS stimulants (e.g. MDMA), 5-HT1 agonists (e.g. triptans), herbs and others.

Serotonergic psychedelics are agonists not only of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor but also of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor and other serotonin receptors. A potential risk of frequent repeated use of serotonergic psychedelics is cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy caused by 5-HT2B receptor activation. However, single high doses or widely spaced doses (e.g., months) are widely thought to be safe and concerns about cardiac toxicity apply more to chronic psychedelic microdosing or very frequent use (e.g., weekly). Selective 5-HT2A receptor agonists that do not activate the 5-HT2B receptor or other serotonin receptors, such as 25CN-NBOH, DMBMPP, and LPH-5, have been developed and are being studied. Selective 5-HT2A receptor agonists are expected to avoid the cardiac risks of 5-HT2B receptor activation.

Potential therapeutic effects

Psychedelic substances which may have therapeutic uses include psilocybin, LSD, and mescaline. During the 1950s and 1960s, lack of informed consent in some scientific trials on psychedelics led to significant, long-lasting harm to some participants. Since then, research regarding the effectiveness of psychedelic therapy has been conducted under strict ethical guidelines, with fully informed consent and a pre-screening to avoid people with psychosis taking part. Although the history behind these substances has hindered research into their potential medicinal value, scientists are now able to conduct studies and renew research that was halted in the 1970s. Some research has shown that these substances have helped people with such mental disorders as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcoholism, depression, and cluster headaches.

It has long been known that psychedelics promote neurite growth and neuroplasticity and are potent psychoplastogens. There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits. Psychedelics have also been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory activity and therapeutic effects in animal models of inflammatory diseases including asthma, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. They might also be useful for the treatment of neuroinflammation as well as post-COVID-19 syndrome (long COVID).

Surrounding culture

Psychedelic culture includes manifestations such as psychedelic music, psychedelic art, psychedelic literature, psychedelic film, and psychedelic festivals. Examples of psychedelic music would be rock bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and The Beatles. Many psychedelic bands and elements of the psychedelic subculture originated in San Francisco during the mid to late 1960s.

Legal status

Many psychedelics are classified under Schedule I of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 as drugs with the greatest potential to cause harm and no acceptable medical uses. In addition, many countries have analogue laws; for example, in the United States, the Federal Analogue Act of 1986 automatically forbids any drugs sharing similar chemical structures or chemical formulas to prohibited substances if sold for human consumption.

In July 2022, though, under the United States Food and Drug Administration, the drug psilocybin was on track to be approved of as a treatment for depression, and MDMA as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

U.S. states such as Oregon and Colorado have also instituted decriminalization and legalization measures for accessing psychedelics and states like New Hampshire are attempting to do the same. J.D. Tuccille argues that increasing rates of use of psychedelics in defiance of the law are likely to result in more widespread legalization and decriminalization of access to the substances in the United States (as has happened with alcohol and cannabis).