Pharmacogenomics, often abbreviated "PGx," is the study of the role of the genome in drug response. Its name (pharmaco- + genomics) reflects its combining of pharmacology and genomics. Pharmacogenomics analyzes how the genetic makeup of a patient affects their response to drugs. It deals with the influence of acquired and inherited genetic variation on drug response, by correlating DNA mutations (including point mutations, copy number variations, and structural variations) with pharmacokinetic (drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination), pharmacodynamic (effects mediated through a drug's biological targets), and/or immunogenic endpoints.

Pharmacogenomics aims to develop rational means to optimize drug therapy, with regard to the patients' genotype, to achieve maximum efficiency with minimal adverse effects. It is hoped that by using pharmacogenomics, pharmaceutical drug treatments can deviate from what is dubbed as the "one-dose-fits-all" approach. Pharmacogenomics also attempts to eliminate trial-and-error in prescribing, allowing physicians to take into consideration their patient's genes, the functionality of these genes, and how this may affect the effectiveness of the patient's current or future treatments (and where applicable, provide an explanation for the failure of past treatments). Such approaches promise the advent of precision medicine and even personalized medicine, in which drugs and drug combinations are optimized for narrow subsets of patients or even for each individual's unique genetic makeup.

Whether used to explain a patient's response (or lack of it) to a treatment, or to act as a predictive tool, it hopes to achieve better treatment outcomes and greater efficacy, and reduce drug toxicities and adverse drug reactions (ADRs). For patients who do not respond to a treatment, alternative therapies can be prescribed that would best suit their requirements. In order to provide pharmacogenomic recommendations for a given drug, two possible types of input can be used: genotyping, or exome or whole genome sequencing. Sequencing provides many more data points, including detection of mutations that prematurely terminate the synthesized protein (early stop codon).

Pharmacogenetics vs. pharmacogenomics

The term pharmacogenomics is often used interchangeably with pharmacogenetics. Although both terms relate to drug response based on genetic influences, there are differences between the two. Pharmacogenetics is limited to monogenic phenotypes (i.e., single gene-drug interactions). Pharmacogenomics refers to polygenic drug response phenotypes and encompasses transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.

Mechanisms of pharmacogenetic interactions

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics involves the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of pharmaceutics. These processes are often facilitated by enzymes such as drug transporters or drug metabolizing enzymes (discussed in-depth below). Variation in DNA loci responsible for producing these enzymes can alter their expression or activity so that their functional status changes. An increase, decrease, or loss of function for transporters or metabolizing enzymes can ultimately alter the amount of medication in the body and at the site of action. This may result in deviation from the medication's therapeutic window and result in either toxicity or loss of effectiveness.

Drug-metabolizing enzymes

The majority of clinically actionable pharmacogenetic variation occurs in genes that code for drug-metabolizing enzymes, including those involved in both phase I and phase II metabolism. The cytochrome P450 enzyme family is responsible for metabolism of 70-80% of all medications used clinically.[11] CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6 are major CYP enzymes involved in drug metabolism and are all known to be highly polymorphic. Additional drug-metabolizing enzymes that have been implicated in pharmacogenetic interactions include UGT1A1 (a UDP-glucuronosyltransferase), DPYD, and TPMT.

Drug transporters

Many medications rely on transporters to cross cellular membranes in order to move between body fluid compartments such as the blood, gut lumen, bile, urine, brain, and cerebrospinal fluid. The major transporters include the solute carrier, ATP-binding cassette, and organic anion transporters. Transporters that have been shown to influence response to medications include OATP1B1 (SLCO1B1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) (ABCG2).

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics refers to the impact a medication has on the body, or its mechanism of action.

Drug targets

Drug targets are the specific sites where a medication carries out its pharmacological activity. The interaction between the drug and this site results in a modification of the target that may include inhibition or potentiation. Most of the pharmacogenetic interactions that involve drug targets are within the field of oncology and include targeted therapeutics designed to address somatic mutations (see also Cancer Pharmacogenomics). For example, EGFR inhibitors like gefitinib (Iressa) or erlotinib (Tarceva) are only indicated in patients carrying specific mutations to EGFR.

Germline mutations in drug targets can also influence response to medications, though this is an emerging subfield within pharmacogenomics. One well-established gene-drug interaction involving a germline mutation to a drug target is warfarin (Coumadin) and VKORC1, which codes for vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). Warfarin binds to and inhibits VKOR, which is an important enzyme in the vitamin K cycle. Inhibition of VKOR prevents reduction of vitamin K, which is a cofactor required in the formation of coagulation factors II, VII, IX and X, and inhibitors protein C and S.

Off-target sites

Medications can have off-target effects (typically unfavorable) that arise from an interaction between the medication and/or its metabolites and a site other than the intended target. Genetic variation in the off-target sites can influence this interaction. The main example of this type of pharmacogenomic interaction is glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD). G6PD is the enzyme involved in the first step of the pentose phosphate pathway which generates NADPH (from NADP). NADPH is required for the production of reduced glutathione in erythrocytes and it is essential for the function of catalase. Glutathione and catalase protect cells from oxidative stress that would otherwise result in cell lysis. Certain variants in G6PD result in G6PD deficiency, in which cells are more susceptible to oxidative stress. When medications that have a significant oxidative effect are administered to individuals who are G6PD deficient, they are at an increased risk of erythrocyte lysis that presents as hemolytic anemia.

Immunologic

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, also referred to as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), is a complex of genes important for the adaptive immune system. Mutations in the HLA complex have been associated with an increased risk of developing hypersensitivity reactions in response to certain medications.

Clinical pharmacogenomics resources

Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is "an international consortium of individual volunteers and a small dedicated staff who are interested in facilitating use of pharmacogenetic tests for patient care. CPIC’s goal is to address barriers to clinical implementation of pharmacogenetic tests by creating, curating, and posting freely available, peer-reviewed, evidence-based, updatable, and detailed gene/drug clinical practice guidelines. CPIC guidelines follow standardized formats, include systematic grading of evidence and clinical recommendations, use standardized terminology, are peer-reviewed, and are published in a journal (in partnership with Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics) with simultaneous posting to cpicpgx.org, where they are regularly updated."

The CPIC guidelines are "designed to help clinicians understand HOW available genetic test results should be used to optimize drug therapy, rather than WHETHER tests should be ordered. A key assumption underlying the CPIC guidelines is that clinical high-throughput and pre-emptive (pre-prescription) genotyping will become more widespread, and that clinicians will be faced with having patients’ genotypes available even if they have not explicitly ordered a test with a specific drug in mind. CPIC's guidelines, processes and projects have been endorsed by several professional societies."

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations

In February 2020 the FDA published the Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations. For the gene-drug pairs included in the table, "the FDA has evaluated and believes there is sufficient scientific evidence to suggest that subgroups of patients with certain genetic variants, or genetic variant-inferred phenotypes (such as affected subgroup in the table below), are likely to have altered drug metabolism, and in certain cases, differential therapeutic effects, including differences in risks of adverse events."

"The information in this Table is intended primarily for prescribers, and patients should not adjust their medications without consulting their prescriber. This version of the table is limited to pharmacogenetic associations that are related to drug metabolizing enzyme gene variants, drug transporter gene variants, and gene variants that have been related to a predisposition for certain adverse events. The FDA recognizes that various other pharmacogenetic associations exist that are not listed here, and this table will be updated periodically with additional pharmacogenetic associations supported by sufficient scientific evidence."

Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling

The FDA Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labeling lists FDA-approved drugs with pharmacogenomic information found in the drug labeling. "Biomarkers in the table include but are not limited to germline or somatic gene variants (polymorphisms, mutations), functional deficiencies with a genetic etiology, gene expression differences, and chromosomal abnormalities; selected protein biomarkers that are used to select treatments for patients are also included."

PharmGKB

The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB) is an "NIH-funded resource that provides information about how human genetic variation affects response to medications. PharmGKB collects, curates and disseminates knowledge about clinically actionable gene-drug associations and genotype-phenotype relationships."

Commercial Pharmacogenetic Testing Laboratories

There are many commercial laboratories around the world who offer pharmacogenomic testing as a laboratory developed test (LDTs). The tests offered can vary significantly from one lab to another, including genes and alleles tested for, phenotype assignment, and any clinical annotations provided. With the exception of a few direct-to-consumer tests, all pharmacogenetic testing requires an order from an authorized healthcare professional. In order for the results to be used in a clinical setting in the United States, the laboratory performing the test must be CLIA-certified. Other regulations may vary by country and state.

Direct-to-Consumer Pharmacogenetic Testing

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmacogenetic tests allow consumers to obtain pharmacogenetic testing without an order from a prescriber. DTC pharmacogenetic tests are generally reviewed by the FDA to determine the validity of test claims. The FDA maintains a list of DTC genetic tests that have been approved.

Common Pharmacogenomic-Specific Nomenclature

Genotype

There are multiple ways to represent a pharmacogenomic genotype. A commonly used nomenclature system is to report haplotypes using a star (*) allele (e.g., CYP2C19 *1/*2). Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) may be described using their assignment reference SNP cluster ID (rsID) or based on the location of the base pair or amino acid impacted.

Phenotype

In 2017 CPIC published results of an expert survey to standardize terms related to clinical pharmacogenetic test results. Consensus for terms to describe allele functional status, phenotype for drug metabolizing enzymes, phenotype for drug transporters, and phenotype for high-risk genotype status was reached.

Applications

The list below provides a few more commonly known applications of pharmacogenomics:

- Improve drug safety, and reduce ADRs;

- Tailor treatments to meet patients' unique genetic pre-disposition, identifying optimal dosing;

- Improve drug discovery targeted to human disease; and

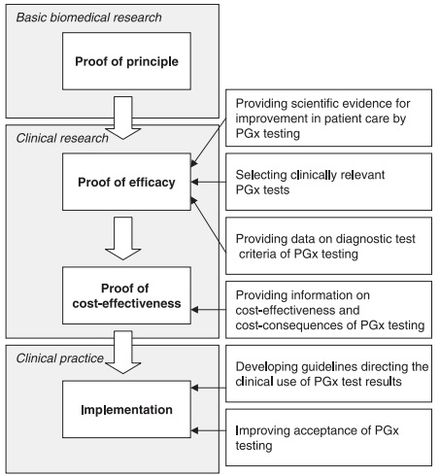

- Improve proof of principle for efficacy trials.

Pharmacogenomics may be applied to several areas of medicine, including pain management, cardiology, oncology, and psychiatry. A place may also exist in forensic pathology, in which pharmacogenomics can be used to determine the cause of death in drug-related deaths where no findings emerge using autopsy.

In cancer treatment, pharmacogenomics tests are used to identify which patients are most likely to respond to certain cancer drugs. In behavioral health, pharmacogenomic tests provide tools for physicians and care givers to better manage medication selection and side effect amelioration. Pharmacogenomics is also known as companion diagnostics, meaning tests being bundled with drugs. Examples include KRAS test with cetuximab and EGFR test with gefitinib. Beside efficacy, germline pharmacogenetics can help to identify patients likely to undergo severe toxicities when given cytotoxics showing impaired detoxification in relation with genetic polymorphism, such as canonical 5-FU. In particular, genetic deregulations affecting genes coding for DPD, UGT1A1, TPMT, CDA and CYP2D6 are now considered as critical issues for patients treated with 5-FU/capecitabine, irinotecan, mercaptopurine/azathioprine, gemcitabine/capecitabine/AraC and tamoxifen, respectively.

In cardiovascular disorders, the main concern is response to drugs including warfarin, clopidogrel, beta blockers, and statins. In patients with CYP2C19, who take clopidogrel, cardiovascular risk is elevated, leading to medication package insert updates by regulators. In patients with type 2 diabetes, haptoglobin (Hp) genotyping shows an effect on cardiovascular disease, with Hp2-2 at higher risk and supplemental vitamin E reducing risk by affecting HDL.

In psychiatry, as of 2010, research has focused particularly on 5-HTTLPR and DRD2.

Clinical implementation

Initiatives to spur adoption by clinicians include the Ubiquitous Pharmacogenomics (U-PGx) program in Europe and the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) in the United States. In a 2017 survey of European clinicians, in the prior year two-thirds had not ordered a pharmacogenetic test.

In 2010, Vanderbilt University Medical Center launched Pharmacogenomic Resource for Enhanced Decisions in Care and Treatment (PREDICT); in 2015 survey, two-thirds of the clinicians had ordered a pharmacogenetic test.

In 2019, the largest private health insurer, UnitedHealthcare, announced that it would pay for genetic testing to predict response to psychiatric drugs.

In 2020, Canada's 4th largest health and dental insurer, Green Shield Canada, announced that it would pay for pharmacogenetic testing and its associated clinical decision support software to optimize and personalize mental health prescriptions.

Reduction of polypharmacy

A potential role for pharmacogenomics is to reduce the occurrence of polypharmacy: it is theorized that with tailored drug treatments, patients will not need to take several medications to treat the same condition. Thus they could potentially reduce the occurrence of adverse drug reactions, improve treatment outcomes, and save costs by avoiding purchase of some medications. For example, maybe due to inappropriate prescribing, psychiatric patients tend to receive more medications than age-matched non-psychiatric patients.

The need for pharmacogenomically tailored drug therapies may be most evident in a survey conducted by the Slone Epidemiology Center at Boston University from February 1998 to April 2007. The study elucidated that an average of 82% of adults in the United States are taking at least one medication (prescription or nonprescription drug, vitamin/mineral, herbal/natural supplement), and 29% are taking five or more. The study suggested that those aged 65 years or older continue to be the biggest consumers of medications, with 17-19% in this age group taking at least ten medications in a given week. Polypharmacy has also shown to have increased since 2000 from 23% to 29%.

Example case studies

Case A – Antipsychotic adverse reaction

Patient A has schizophrenia. Their treatment included a combination of ziprasidone, olanzapine, trazodone and benztropine. The patient experienced dizziness and sedation, so they were tapered off ziprasidone and olanzapine, and transitioned to quetiapine. Trazodone was discontinued. The patient then experienced excessive sweating, tachycardia and neck pain, gained considerable weight and had hallucinations. Five months later, quetiapine was tapered and discontinued, with ziprasidone re-introduced into their treatment, due to the excessive weight gain. Although the patient lost the excessive weight they had gained, they then developed muscle stiffness, cogwheeling, tremors and night sweats. When benztropine was added they experienced blurry vision. After an additional five months, the patient was switched from ziprasidone to aripiprazole. Over the course of 8 months, patient A gradually experienced more weight gain and sedation, and developed difficulty with their gait, stiffness, cogwheeling and dyskinetic ocular movements. A pharmacogenomics test later proved the patient had a CYP2D6 *1/*41, which has a predicted phenotype of IM and CYP2C19 *1/*2 with a predicted phenotype of IM as well.

Case B – Pain Management

Patient B is a woman who gave birth by caesarian section. Her physician prescribed codeine for post-caesarian pain. She took the standard prescribed dose, but she experienced nausea and dizziness while she was taking codeine. She also noticed that her breastfed infant was lethargic and feeding poorly. When the patient mentioned these symptoms to her physician, they recommended that she discontinue codeine use. Within a few days, both the patient's and her infant's symptoms were no longer present. It is assumed that if the patient had undergone a pharmacogenomic test, it would have revealed she may have had a duplication of the gene CYP2D6, placing her in the Ultra-rapid metabolizer (UM) category, explaining her reactions to codeine use.

Case C – FDA Warning on Codeine Overdose for Infants

On February 20, 2013, the FDA released a statement addressing a serious concern regarding the connection between children who are known as CYP2D6 UM, and fatal reactions to codeine following tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy (surgery to remove the tonsils and/or adenoids). They released their strongest Boxed Warning to elucidate the dangers of CYP2D6 UMs consuming codeine. Codeine is converted to morphine by CYP2D6, and those who have UM phenotypes are in danger of producing large amounts of morphine due to the increased function of the gene. The morphine can elevate to life-threatening or fatal amounts, as became evident with the death of three children in August 2012.

Challenges

Although there appears to be a general acceptance of the basic tenet of pharmacogenomics amongst physicians and healthcare professionals, several challenges exist that slow the uptake, implementation, and standardization of pharmacogenomics. Some of the concerns raised by physicians include:

- Limitation on how to apply the test into clinical practices and treatment;

- A general feeling of lack of availability of the test;

- The understanding and interpretation of evidence-based research;

- Combining test results with other patient data for prescription optimization; and

- Ethical, legal and social issues.

Issues surrounding the availability of the test include:

- The lack of availability of scientific data: Although there are a considerable number of drug-metabolizing enzymes involved in the metabolic pathways of drugs, only a fraction have sufficient scientific data to validate their use within a clinical setting; and

- Demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenomics: Publications for the pharmacoeconomics of pharmacogenomics are scarce, therefore sufficient evidence does not at this time exist to validate the cost-effectiveness and cost-consequences of the test.

Although other factors contribute to the slow progression of pharmacogenomics (such as developing guidelines for clinical use), the above factors appear to be the most prevalent. Increasingly substantial evidence and industry body guidelines for clinical use of pharmacogenetics have made it a population wide approach to precision medicine. Cost, reimbursement, education, and easy use at the point of care remain significant barriers to widescale adoption.

Controversies

Race-based medicine

There has been call to move away from race and ethnicity in medicine and instead use genetic ancestry as a way to categorize patients. Some alleles that vary in frequency between specific populations have been shown to be associated with differential responses to specific drugs. As a result, some disease-specific guidelines only recommend pharmacogenetic testing for populations where high-risk alleles are more common and, similarly, certain insurance companies will only pay for pharmacogenetic testing for beneficiaries of high-risk populations.

Genetic exceptionalism

In the early 2000s, handling genetic information as exceptional, including legal or regulatory protections, garnered strong support. It was argued that genomic information may need special policy and practice protections within the context of electronic health records (EHRs). In 2008, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) was enacted to protect patients from health insurance companies discriminating against an individual based on genetic information.

More recently it has been argued that genetic exceptionalism is past its expiration date as we move into a blended genomic/big data era of medicine, yet exceptionalism practices continue to permeate clinical healthcare today. Garrison et al. recently relayed a call to action to update verbiage from genetic exceptionalism to genomic contextualism in that we recognize a fundamental duality of genetic information. This allows room in the argument for different types of genetic information to be handled differently while acknowledging that genomic information is similar and yet distinct from other health-related information. Genomic contextualism would allow for a case-by-case analysis of the technology and the context of its use (e.g., clinical practice, research, secondary findings).

Others argue that genetic information is indeed distinct from other health-related information but not to the extent of requiring legal/regulatory protections, similar to other sensitive health-related data such as HIV status. Additionally, Evans et al. argue that the EHR has sufficient privacy standards to hold other sensitive information such as social security numbers and that the fundamental nature of an EHR is to house highly personal information. Similarly, a systematic review reported that the public had concern over privacy of genetic information, with 60% agreeing that maintaining privacy was not possible; however, 96% agreed that a direct-to-consumer testing company had protected their privacy, with 74% saying their information would be similarly or better protected in an EHR. With increasing technological capabilities in EHRs, it is possible to mask or hide genetic data from subsets of providers and there is not consensus on how, when, or from whom genetic information should be masked. Rigorous protection and masking of genetic information is argued to impede further scientific progress and clinical translation into routine clinical practices.

History

Pharmacogenomics was first recognized by Pythagoras around 510 BC when he made a connection between the dangers of fava bean ingestion with hemolytic anemia and oxidative stress. In the 1950s, this identification was validated and attributed to deficiency of G6PD and is called favism. Although the first official publication was not until 1961, the unofficial beginnings of this science were around the 1950s. Reports of prolonged paralysis and fatal reactions linked to genetic variants in patients who lacked butyrylcholinesterase ('pseudocholinesterase') following succinylcholine injection during anesthesia were first reported in 1956. The term pharmacogenetics was first coined in 1959 by Friedrich Vogel of Heidelberg, Germany (although some papers suggest it was 1957 or 1958). In the late 1960s, twin studies supported the inference of genetic involvement in drug metabolism, with identical twins sharing remarkable similarities in drug response compared to fraternal twins. The term pharmacogenomics first began appearing around the 1990s.

The first FDA approval of a pharmacogenetic test was in 2005 (for alleles in CYP2D6 and CYP2C19)

Future

Computational advances have enabled cheaper and faster sequencing. Research has focused on combinatorial chemistry, genomic mining, omic technologies, and high throughput screening.

As the cost per genetic test decreases, the development of personalized drug therapies will increase. Technology now allows for genetic analysis of hundreds of target genes involved in medication metabolism and response in less than 24 hours for under $1,000. This a huge step towards bringing pharmacogenetic technology into everyday medical decisions. Likewise, companies like deCODE genetics, MD Labs Pharmacogenetics, Navigenics and 23andMe offer genome scans. The companies use the same genotyping chips that are used in GWAS studies and provide customers with a write-up of individual risk for various traits and diseases and testing for 500,000 known SNPs. Costs range from $995 to $2500 and include updates with new data from studies as they become available. The more expensive packages even included a telephone session with a genetics counselor to discuss the results.