Extinction is the termination of a taxon by the death of its last member. A taxon may become functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to reproduce and recover. Because a species' potential range may be very large, determining this moment is difficult, and is usually done retrospectively. This difficulty leads to phenomena such as Lazarus taxa, where a species presumed extinct abruptly "reappears" (typically in the fossil record) after a period of apparent absence.

More than 99% of all species that ever lived on Earth, amounting to over five billion species, are estimated to have died out. It is estimated that there are currently around 8.7 million species of eukaryotes globally, and possibly many times more if microorganisms, such as bacteria, are included. Notable extinct animal species include non-avian dinosaurs, palaeotheres, saber-toothed cats, dodos, mammoths, ground sloths, thylacines, trilobites, golden toads, and passenger pigeons.

Through evolution, species arise through the process of speciation—where new varieties of organisms arise and thrive when they are able to find and exploit an ecological niche—and species become extinct when they are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition. The relationship between animals and their ecological niches has been firmly established. A typical species becomes extinct within 10 million years of its first appearance, although some species, called living fossils, survive with little to no morphological change for hundreds of millions of years.

Mass extinctions are relatively rare events; however, isolated extinctions of species and clades are quite common, and are a natural part of the evolutionary process. Only recently have extinctions been recorded and scientists have become alarmed at the current high rate of extinctions. Most species that become extinct are never scientifically documented. Some scientists estimate that up to half of presently existing plant and animal species may become extinct by 2100. A 2018 report indicated that the phylogenetic diversity of 300 mammalian species erased during the human era since the Late Pleistocene would require 5 to 7 million years to recover.

According to the 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by IPBES, the biomass of wild mammals has fallen by 82%, natural ecosystems have lost about half their area and a million species are at risk of extinction—all largely as a result of human actions. Twenty-five percent of plant and animal species are threatened with extinction. In a subsequent report, IPBES listed unsustainable fishing, hunting and logging as being some of the primary drivers of the global extinction crisis.

In June 2019, one million species of plants and animals were at risk of extinction. At least 571 plant species have been lost since 1750, but likely many more. The main cause of the extinctions is the destruction of natural habitats by human activities, such as cutting down forests and converting land into fields for farming.

A dagger symbol (†) placed next to the name of a species or other taxon normally indicates its status as extinct.

Examples

Examples of species and subspecies that are extinct include:

- Steller's sea cow (the last known member died circa 1768)

- Dodo (the last confirmed sighting was in 1662)

- Chinese paddlefish (last seen in 2003; declared extinct in 2022)

- Great auk (last confirmed pair was killed in the 1840s)

- Thylacine (the last thylacine killed in the wild was shot in 1930; the last captive tiger lived in Hobart Zoo until 1936)

- Kauai O'o (last known member was heard in 1987; the entire Mohoidae family became extinct with it)

- Spectacled cormorant (last known members were said to live in the 1850s)

- Carolina parakeet (last known member named Incas died in captivity in 1918; declared extinct in 1939)

- Passenger pigeon (last known member named Martha died in captivity in 1914)

- Tasmanian emu (the last claimed sighting of the emu was in 1839)

- Japanese Sea Lion (the last confirmed record was a juvenile specimen captured in 1974)

- Schomburgk's deer (became extinct in the wild in 1932; the last captive deer was killed in 1938)

- Quagga (hunted to extinction in the late 19th century; the last captive quagga died in Natura Artis Magistra in 1883)

Definition

A species is extinct when the last existing member dies. Extinction therefore becomes a certainty when there are no surviving individuals that can reproduce and create a new generation. A species may become functionally extinct when only a handful of individuals survive, which cannot reproduce due to poor health, age, sparse distribution over a large range, a lack of individuals of both sexes (in sexually reproducing species), or other reasons.

Pinpointing the extinction (or pseudoextinction) of a species requires a clear definition of that species. If it is to be declared extinct, the species in question must be uniquely distinguishable from any ancestor or daughter species, and from any other closely related species. Extinction of a species (or replacement by a daughter species) plays a key role in the punctuated equilibrium hypothesis of Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge.

In ecology, extinction is sometimes used informally to refer to local extinction, in which a species ceases to exist in the chosen area of study, despite still existing elsewhere. Local extinctions may be made good by the reintroduction of individuals of that species taken from other locations; wolf reintroduction is an example of this. Species that are not globally extinct are termed extant. Those species that are extant, yet are threatened with extinction, are referred to as threatened or endangered species.

Currently, an important aspect of extinction is human attempts to preserve critically endangered species. These are reflected by the creation of the conservation status "extinct in the wild" (EW). Species listed under this status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are not known to have any living specimens in the wild and are maintained only in zoos or other artificial environments. Some of these species are functionally extinct, as they are no longer part of their natural habitat and it is unlikely the species will ever be restored to the wild. When possible, modern zoological institutions try to maintain a viable population for species preservation and possible future reintroduction to the wild, through use of carefully planned breeding programs.

The extinction of one species' wild population can have knock-on effects, causing further extinctions. These are also called "chains of extinction". This is especially common with extinction of keystone species.

A 2018 study indicated that the sixth mass extinction started in the Late Pleistocene could take up to 5 to 7 million years to restore mammal diversity to what it was before the human era.

Pseudoextinction

Extinction of a parent species where daughter species or subspecies are still extant is called pseudoextinction or phyletic extinction. Effectively, the old taxon vanishes, transformed (anagenesis) into a successor, or split into more than one (cladogenesis).

Pseudoextinction is difficult to demonstrate unless one has a strong chain of evidence linking a living species to members of a pre-existing species. For example, it is sometimes claimed that the extinct Hyracotherium, which was an early horse that shares a common ancestor with the modern horse, is pseudoextinct, rather than extinct, because there are several extant species of Equus, including zebra and donkey; however, as fossil species typically leave no genetic material behind, one cannot say whether Hyracotherium evolved into more modern horse species or merely evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses. Pseudoextinction is much easier to demonstrate for larger taxonomic groups.

Lazarus taxa

A Lazarus taxon or Lazarus species refers to instances where a species or taxon was thought to be extinct, but was later rediscovered. It can also refer to instances where large gaps in the fossil record of a taxon result in fossils reappearing much later, although the taxon may have ultimately become extinct at a later point.

The coelacanth, a fish related to lungfish and tetrapods, is an example of a Lazarus taxon that was known only from the fossil record and was considered to have been extinct since the end of the Cretaceous Period. In 1938, however, a living specimen was found off the Chalumna River (now Tyolomnqa) on the east coast of South Africa. Calliostoma bullatum, a species of deepwater sea snail originally described from fossils in 1844 proved to be a Lazarus species when extant individuals were described in 2019.

Attenborough's long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus attenboroughi) is an example of a Lazarus species from Papua New Guinea that had last been sighted in 1962 and believed to be possibly extinct, until it was recorded again in November 2023.

Some species currently thought to be extinct have had continued speculation that they may still exist, and in the event of rediscovery would be considered Lazarus species. Examples include the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), the last known example of which died in Hobart Zoo in Tasmania in 1936; the Japanese wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax), last sighted over 100 years ago; the American ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), with the last universally accepted sighting in 1944; and the slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris), not seen since 2007.

Causes

As long as species have been evolving, species have been going extinct. It is estimated that over 99.9% of all species that ever lived are extinct. The average lifespan of a species is 1–10 million years, although this varies widely between taxa. A variety of causes can contribute directly or indirectly to the extinction of a species or group of species. "Just as each species is unique", write Beverly and Stephen C. Stearns, "so is each extinction ... the causes for each are varied—some subtle and complex, others obvious and simple". Most simply, any species that cannot survive and reproduce in its environment and cannot move to a new environment where it can do so, dies out and becomes extinct. Extinction of a species may come suddenly when an otherwise healthy species is wiped out completely, as when toxic pollution renders its entire habitat unliveable; or may occur gradually over thousands or millions of years, such as when a species gradually loses out in competition for food to better adapted competitors. Extinction may occur a long time after the events that set it in motion, a phenomenon known as extinction debt.

Assessing the relative importance of genetic factors compared to environmental ones as the causes of extinction has been compared to the debate on nature and nurture. The question of whether more extinctions in the fossil record have been caused by evolution or by competition or by predation or by disease or by catastrophe is a subject of discussion; Mark Newman, the author of Modeling Extinction, argues for a mathematical model that falls in all positions. By contrast, conservation biology uses the extinction vortex model to classify extinctions by cause. When concerns about human extinction have been raised, for example in Sir Martin Rees' 2003 book Our Final Hour, those concerns lie with the effects of climate change or technological disaster.

Human-driven extinction started as humans migrated out of Africa more than 60,000 years ago. Currently, environmental groups and some governments are concerned with the extinction of species caused by humanity, and they try to prevent further extinctions through a variety of conservation programs. Humans can cause extinction of a species through overharvesting, pollution, habitat destruction, introduction of invasive species (such as new predators and food competitors), overhunting, and other influences. Explosive, unsustainable human population growth and increasing per capita consumption are essential drivers of the extinction crisis. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), 784 extinctions have been recorded since the year 1500, the arbitrary date selected to define "recent" extinctions, up to the year 2004; with many more likely to have gone unnoticed. Several species have also been listed as extinct since 2004.

Genetics and demographic phenomena

If adaptation increasing population fitness is slower than environmental degradation plus the accumulation of slightly deleterious mutations, then a population will go extinct. Smaller populations have fewer beneficial mutations entering the population each generation, slowing adaptation. It is also easier for slightly deleterious mutations to fix in small populations; the resulting positive feedback loop between small population size and low fitness can cause mutational meltdown.

Limited geographic range is the most important determinant of genus extinction at background rates but becomes increasingly irrelevant as mass extinction arises. Limited geographic range is a cause both of small population size and of greater vulnerability to local environmental catastrophes.

Extinction rates can be affected not just by population size, but by any factor that affects evolvability, including balancing selection, cryptic genetic variation, phenotypic plasticity, and robustness. A diverse or deep gene pool gives a population a higher chance in the short term of surviving an adverse change in conditions. Effects that cause or reward a loss in genetic diversity can increase the chances of extinction of a species. Population bottlenecks can dramatically reduce genetic diversity by severely limiting the number of reproducing individuals and make inbreeding more frequent.

Genetic pollution

Extinction sometimes results for species evolved to specific ecologies that are subjected to genetic pollution—i.e., uncontrolled hybridization, introgression and genetic swamping that lead to homogenization or out-competition from the introduced (or hybrid) species. Endemic populations can face such extinctions when new populations are imported or selectively bred by people, or when habitat modification brings previously isolated species into contact. Extinction is likeliest for rare species coming into contact with more abundant ones; interbreeding can swamp the rarer gene pool and create hybrids, depleting the purebred gene pool (for example, the endangered wild water buffalo is most threatened with extinction by genetic pollution from the abundant domestic water buffalo). Such extinctions are not always apparent from morphological (non-genetic) observations. Some degree of gene flow is a normal evolutionary process; nevertheless, hybridization (with or without introgression) threatens rare species' existence.

The gene pool of a species or a population is the variety of genetic information in its living members. A large gene pool (extensive genetic diversity) is associated with robust populations that can survive bouts of intense selection. Meanwhile, low genetic diversity (see inbreeding and population bottlenecks) reduces the range of adaptions possible. Replacing native with alien genes narrows genetic diversity within the original population, thereby increasing the chance of extinction.

Habitat degradation

Habitat degradation is currently the main anthropogenic cause of species extinctions. The main cause of habitat degradation worldwide is agriculture, with urban sprawl, logging, mining, and some fishing practices close behind. The degradation of a species' habitat may alter the fitness landscape to such an extent that the species is no longer able to survive and becomes extinct. This may occur by direct effects, such as the environment becoming toxic, or indirectly, by limiting a species' ability to compete effectively for diminished resources or against new competitor species.

Habitat destruction, particularly the removal of vegetation that stabilizes soil, enhances erosion and diminishes nutrient availability in terrestrial ecosystems. This degradation can lead to a reduction in agricultural productivity. Furthermore, increased erosion contributes to poorer water quality by elevating the levels of sediment and pollutants in rivers and streams.

Habitat degradation through toxicity can kill off a species very rapidly, by killing all living members through contamination or sterilizing them. It can also occur over longer periods at lower toxicity levels by affecting life span, reproductive capacity, or competitiveness.

Habitat degradation can also take the form of a physical destruction of niche habitats. The widespread destruction of tropical rainforests and replacement with open pastureland is widely cited as an example of this; elimination of the dense forest eliminated the infrastructure needed by many species to survive. For example, a fern that depends on dense shade for protection from direct sunlight can no longer survive without forest to shelter it. Another example is the destruction of ocean floors by bottom trawling.

Diminished resources or introduction of new competitor species also often accompany habitat degradation. Global warming has allowed some species to expand their range, bringing competition to other species that previously occupied that area. Sometimes these new competitors are predators and directly affect prey species, while at other times they may merely outcompete vulnerable species for limited resources. Vital resources including water and food can also be limited during habitat degradation, leading to extinction.

Predation, competition, and disease

In the natural course of events, species become extinct for a number of reasons, including but not limited to: extinction of a necessary host, prey or pollinator, interspecific competition, inability to deal with evolving diseases and changing environmental conditions (particularly sudden changes) which can act to introduce novel predators, or to remove prey. Recently in geological time, humans have become an additional cause of extinction of some species, either as a new mega-predator or by transporting animals and plants from one part of the world to another. Such introductions have been occurring for thousands of years, sometimes intentionally (e.g. livestock released by sailors on islands as a future source of food) and sometimes accidentally (e.g. rats escaping from boats). In most cases, the introductions are unsuccessful, but when an invasive alien species does become established, the consequences can be catastrophic. Invasive alien species can affect native species directly by eating them, competing with them, and introducing pathogens or parasites that sicken or kill them; or indirectly by destroying or degrading their habitat. Human populations may themselves act as invasive predators. According to the "overkill hypothesis", the swift extinction of the megafauna in areas such as Australia (40,000 years before present), North and South America (12,000 years before present), Madagascar, Hawaii (AD 300–1000), and New Zealand (AD 1300–1500), resulted from the sudden introduction of human beings to environments full of animals that had never seen them before and were therefore completely unadapted to their predation techniques.

Coextinction

Coextinction refers to the loss of a species due to the extinction of another; for example, the extinction of parasitic insects following the loss of their hosts. Coextinction can also occur when a species loses its pollinator, or to predators in a food chain who lose their prey. "Species coextinction is a manifestation of one of the interconnectednesses of organisms in complex ecosystems ... While coextinction may not be the most important cause of species extinctions, it is certainly an insidious one." Coextinction is especially common when a keystone species goes extinct. Models suggest that coextinction is the most common form of biodiversity loss. There may be a cascade of coextinction across the trophic levels. Such effects are most severe in mutualistic and parasitic relationships. An example of coextinction is the Haast's eagle and the moa: the Haast's eagle was a predator that became extinct because its food source became extinct. The moa were several species of flightless birds that were a food source for the Haast's eagle.

Climate change

Extinction as a result of climate change has been confirmed by fossil studies. Particularly, the extinction of amphibians during the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse, 305 million years ago. A 2003 review across 14 biodiversity research centers predicted that, because of climate change, 15–37% of land species would be "committed to extinction" by 2050. The ecologically rich areas that would potentially suffer the heaviest losses include the Cape Floristic Region and the Caribbean Basin. These areas might see a doubling of present carbon dioxide levels and rising temperatures that could eliminate 56,000 plant and 3,700 animal species. Climate change has also been found to be a factor in habitat loss and desertification.

Sexual selection and male investment

Studies of fossils following species from the time they evolved to their extinction show that species with high sexual dimorphism, especially characteristics in males that are used to compete for mating, are at a higher risk of extinction and die out faster than less sexually dimorphic species, the least sexually dimorphic species surviving for millions of years while the most sexually dimorphic species die out within mere thousands of years. Earlier studies based on counting the number of currently living species in modern taxa have shown a higher number of species in more sexually dimorphic taxa which have been interpreted as higher survival in taxa with more sexual selection, but such studies of modern species only measure indirect effects of extinction and are subject to error sources such as dying and doomed taxa speciating more due to splitting of habitat ranges into more small isolated groups during the habitat retreat of taxa approaching extinction. Possible causes of the higher extinction risk in species with more sexual selection shown by the comprehensive fossil studies that rule out such error sources include expensive sexually selected ornaments having negative effects on the ability to survive natural selection, as well as sexual selection removing a diversity of genes that under current ecological conditions are neutral for natural selection but some of which may be important for surviving climate change.

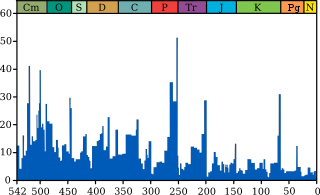

Mass extinctions

There have been at least five mass extinctions in the history of life on earth, and four in the last 350 million years in which many species have disappeared in a relatively short period of geological time. A massive eruptive event that released large quantities of tephra particles into the atmosphere is considered to be one likely cause of the "Permian–Triassic extinction event" about 250 million years ago, which is estimated to have killed 90% of species then existing. There is also evidence to suggest that this event was preceded by another mass extinction, known as Olson's Extinction. The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (K–Pg) occurred 66 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period; it is best known for having wiped out non-avian dinosaurs, among many other species.

Modern extinctions

According to a 1998 survey of 400 biologists conducted by New York's American Museum of Natural History, nearly 70% believed that the Earth is currently in the early stages of a human-caused mass extinction, known as the Holocene extinction. In that survey, the same proportion of respondents agreed with the prediction that up to 20% of all living populations could become extinct within 30 years (by 2028). A 2014 special edition of Science declared there is widespread consensus on the issue of human-driven mass species extinctions. A 2020 study published in PNAS stated that the contemporary extinction crisis "may be the most serious environmental threat to the persistence of civilization, because it is irreversible."

Biologist E. O. Wilson estimated in 2002 that if current rates of human destruction of the biosphere continue, one-half of all plant and animal species of life on earth will be extinct in 100 years. More significantly, the current rate of global species extinctions is estimated as 100 to 1,000 times "background" rates (the average extinction rates in the evolutionary time scale of planet Earth), faster than at any other time in human history, while future rates are likely 10,000 times higher. However, some groups are going extinct much faster. Biologists Paul R. Ehrlich and Stuart Pimm, among others, contend that human population growth and overconsumption are the main drivers of the modern extinction crisis.

In January 2020, the UN's Convention on Biological Diversity drafted a plan to mitigate the contemporary extinction crisis by establishing a deadline of 2030 to protect 30% of the Earth's land and oceans and reduce pollution by 50%, with the goal of allowing for the restoration of ecosystems by 2050. The 2020 United Nations' Global Biodiversity Outlook report stated that of the 20 biodiversity goals laid out by the Aichi Biodiversity Targets in 2010, only 6 were "partially achieved" by the deadline of 2020. The report warned that biodiversity will continue to decline if the status quo is not changed, in particular the "currently unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, population growth and technological developments". In a 2021 report published in the journal Frontiers in Conservation Science, some top scientists asserted that even if the Aichi Biodiversity Targets set for 2020 had been achieved, it would not have resulted in a significant mitigation of biodiversity loss. They added that failure of the global community to reach these targets is hardly surprising given that biodiversity loss is "nowhere close to the top of any country's priorities, trailing far behind other concerns such as employment, healthcare, economic growth, or currency stability."

History of scientific understanding

For much of history, the modern understanding of extinction as the end of a species was incompatible with the prevailing worldview. Prior to the 19th century, much of Western society adhered to the belief that the world was created by God and as such was complete and perfect. This concept reached its heyday in the 1700s with the peak popularity of a theological concept called the great chain of being, in which all life on earth, from the tiniest microorganism to God, is linked in a continuous chain. The extinction of a species was impossible under this model, as it would create gaps or missing links in the chain and destroy the natural order. Thomas Jefferson was a firm supporter of the great chain of being and an opponent of extinction, famously denying the extinction of the woolly mammoth on the grounds that nature never allows a race of animals to become extinct.

A series of fossils were discovered in the late 17th century that appeared unlike any living species. As a result, the scientific community embarked on a voyage of creative rationalization, seeking to understand what had happened to these species within a framework that did not account for total extinction. In October 1686, Robert Hooke presented an impression of a nautilus to the Royal Society that was more than two feet in diameter, and morphologically distinct from any known living species. Hooke theorized that this was simply because the species lived in the deep ocean and no one had discovered them yet. While he contended that it was possible a species could be "lost", he thought this highly unlikely. Similarly, in 1695, Sir Thomas Molyneux published an account of enormous antlers found in Ireland that did not belong to any extant taxa in that area. Molyneux reasoned that they came from the North American moose and that the animal had once been common on the British Isles. Rather than suggest that this indicated the possibility of species going extinct, he argued that although organisms could become locally extinct, they could never be entirely lost and would continue to exist in some unknown region of the globe. The antlers were later confirmed to be from the extinct deer Megaloceros. Hooke and Molyneux's line of thinking was difficult to disprove. When parts of the world had not been thoroughly examined and charted, scientists could not rule out that animals found only in the fossil record were not simply "hiding" in unexplored regions of the Earth.

Georges Cuvier is credited with establishing the modern conception of extinction in a 1796 lecture to the French Institute, though he would spend most of his career trying to convince the wider scientific community of his theory. Cuvier was a well-regarded geologist, lauded for his ability to reconstruct the anatomy of an unknown species from a few fragments of bone. His primary evidence for extinction came from mammoth skulls found near Paris. Cuvier recognized them as distinct from any known living species of elephant, and argued that it was highly unlikely such an enormous animal would go undiscovered. In 1798, he studied a fossil from the Paris Basin that was first observed by Robert de Lamanon in 1782, first hypothesizing that it belonged to a canine but then deciding that it instead belonged to an animal that was unlike living ones. His study paved the way to his naming of the extinct mammal genus Palaeotherium in 1804 based on the skull and additional fossil material along with another extinct contemporary mammal genus Anoplotherium. In both genera, he noticed that their fossils shared some similarities with other mammals like ruminants and rhinoceroses but still had distinct differences. In 1812, Cuvier, along with Alexandre Brongniart and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, mapped the strata of the Paris basin. They saw alternating saltwater and freshwater deposits, as well as patterns of the appearance and disappearance of fossils throughout the record. From these patterns, Cuvier inferred historic cycles of catastrophic flooding, extinction, and repopulation of the earth with new species.

Cuvier's fossil evidence showed that very different life forms existed in the past than those that exist today, a fact that was accepted by most scientists. The primary debate focused on whether this turnover caused by extinction was gradual or abrupt in nature. Cuvier understood extinction to be the result of cataclysmic events that wipe out huge numbers of species, as opposed to the gradual decline of a species over time. His catastrophic view of the nature of extinction garnered him many opponents in the newly emerging school of uniformitarianism.

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, a gradualist and colleague of Cuvier, saw the fossils of different life forms as evidence of the mutable character of species. While Lamarck did not deny the possibility of extinction, he believed that it was exceptional and rare and that most of the change in species over time was due to gradual change. Unlike Cuvier, Lamarck was skeptical that catastrophic events of a scale large enough to cause total extinction were possible. In his geological history of the earth titled Hydrogeologie, Lamarck instead argued that the surface of the earth was shaped by gradual erosion and deposition by water, and that species changed over time in response to the changing environment.

Charles Lyell, a noted geologist and founder of uniformitarianism, believed that past processes should be understood using present day processes. Like Lamarck, Lyell acknowledged that extinction could occur, noting the total extinction of the dodo and the extirpation of indigenous horses to the British Isles. He similarly argued against mass extinctions, believing that any extinction must be a gradual process. Lyell also showed that Cuvier's original interpretation of the Parisian strata was incorrect. Instead of the catastrophic floods inferred by Cuvier, Lyell demonstrated that patterns of saltwater and freshwater deposits, like those seen in the Paris basin, could be formed by a slow rise and fall of sea levels.

The concept of extinction was integral to Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, with less fit lineages disappearing over time. For Darwin, extinction was a constant side effect of competition. Because of the wide reach of On the Origin of Species, it was widely accepted that extinction occurred gradually and evenly (a concept now referred to as background extinction). It was not until 1982, when David Raup and Jack Sepkoski published their seminal paper on mass extinctions, that Cuvier was vindicated and catastrophic extinction was accepted as an important mechanism. The current understanding of extinction is a synthesis of the cataclysmic extinction events proposed by Cuvier, and the background extinction events proposed by Lyell and Darwin.

Human attitudes and interests

Extinction is an important research topic in the field of zoology, and biology in general, and has also become an area of concern outside the scientific community. A number of organizations, such as the Worldwide Fund for Nature, have been created with the goal of preserving species from extinction. Governments have attempted, through enacting laws, to avoid habitat destruction, agricultural over-harvesting, and pollution. While many human-caused extinctions have been accidental, humans have also engaged in the deliberate destruction of some species, such as dangerous viruses, and the total destruction of other problematic species has been suggested. Other species were deliberately driven to extinction, or nearly so, due to poaching or because they were "undesirable", or to push for other human agendas. One example was the near extinction of the American bison, which was nearly wiped out by mass hunts sanctioned by the United States government, to force the removal of Native Americans, many of whom relied on the bison for food.

Biologist Bruce Walsh states three reasons for scientific interest in the preservation of species: genetic resources, ecosystem stability, and ethics; and today the scientific community "stress[es] the importance" of maintaining biodiversity.

In modern times, commercial and industrial interests often have to contend with the effects of production on plant and animal life. However, some technologies with minimal, or no, proven harmful effects on Homo sapiens can be devastating to wildlife (for example, DDT). Biogeographer Jared Diamond notes that while big business may label environmental concerns as "exaggerated", and often cause "devastating damage", some corporations find it in their interest to adopt good conservation practices, and even engage in preservation efforts that surpass those taken by national parks.

Governments sometimes see the loss of native species as a loss to ecotourism, and can enact laws with severe punishment against the trade in native species in an effort to prevent extinction in the wild. Nature preserves are created by governments as a means to provide continuing habitats to species crowded by human expansion. The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity has resulted in international Biodiversity Action Plan programmes, which attempt to provide comprehensive guidelines for government biodiversity conservation. Advocacy groups, such as The Wildlands Project and the Alliance for Zero Extinctions, work to educate the public and pressure governments into action.

People who live close to nature can be dependent on the survival of all the species in their environment, leaving them highly exposed to extinction risks. However, people prioritize day-to-day survival over species conservation; with human overpopulation in tropical developing countries, there has been enormous pressure on forests due to subsistence agriculture, including slash-and-burn agricultural techniques that can reduce endangered species's habitats.

Antinatalist philosopher David Benatar concludes that any popular concern about non-human species extinction usually arises out of concern about how the loss of a species will impact human wants and needs, that "we shall live in a world impoverished by the loss of one aspect of faunal diversity, that we shall no longer be able to behold or use that species of animal." He notes that typical concerns about possible human extinction, such as the loss of individual members, are not considered in regards to non-human species extinction. Anthropologist Jason Hickel speculates that the reason humanity seems largely indifferent to anthropogenic mass species extinction is that we see ourselves as separate from the natural world and the organisms within it. He says that this is due in part to the logic of capitalism: "that the world is not really alive, and it is certainly not our kin, but rather just stuff to be extracted and discarded – and that includes most of the human beings living here too."

Planned extinction

Completed

- The smallpox virus is now extinct in the wild, although samples are retained in laboratory settings.

- The rinderpest virus, which infected domestic cattle, is now extinct in the wild.

Proposed

Disease agents

The poliovirus is now confined to small parts of the world due to extermination efforts.

Dracunculus medinensis, or Guinea worm, a parasitic worm which causes the disease dracunculiasis, is now close to eradication thanks to efforts led by the Carter Center.

Treponema pallidum pertenue, a bacterium which causes the disease yaws, is in the process of being eradicated.

Disease vectors

Biologist Olivia Judson has advocated the deliberate extinction of certain disease-carrying mosquito species. In a September 25, 2003 article in The New York Times, she advocated "specicide" of thirty mosquito species by introducing a genetic element that can insert itself into another crucial gene, to create recessive "knockout genes". She says that the Anopheles mosquitoes (which spread malaria) and Aedes mosquitoes (which spread dengue fever, yellow fever, elephantiasis, and other diseases) represent only 30 of around 3,500 mosquito species; eradicating these would save at least one million human lives per year, at a cost of reducing the genetic diversity of the family Culicidae by only 1%. She further argues that since species become extinct "all the time" the disappearance of a few more will not destroy the ecosystem: "We're not left with a wasteland every time a species vanishes. Removing one species sometimes causes shifts in the populations of other species—but different need not mean worse." In addition, anti-malarial and mosquito control programs offer little realistic hope to the 300 million people in developing nations who will be infected with acute illnesses this year. Although trials are ongoing, she writes that if they fail "we should consider the ultimate swatting."

Biologist E. O. Wilson has advocated the eradication of several species of mosquito, including malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Wilson stated, "I'm talking about a very small number of species that have co-evolved with us and are preying on humans, so it would certainly be acceptable to remove them. I believe it's just common sense."

There have been many campaigns – some successful – to locally eradicate tsetse flies and their trypanosomes in areas, countries, and islands of Africa (including Príncipe). There are currently serious efforts to do away with them all across Africa, and this is generally viewed as beneficial and morally necessary, although not always.

Cloning

Some, such as Harvard geneticist George M. Church, believe that ongoing technological advances will let us "bring back to life" an extinct species by cloning, using DNA from the remains of that species. Proposed targets for cloning include the mammoth, the thylacine, and the Pyrenean ibex. For this to succeed, enough individuals would have to be cloned, from the DNA of different individuals (in the case of sexually reproducing organisms) to create a viable population. Though bioethical and philosophical objections have been raised, the cloning of extinct creatures seems theoretically possible.

In 2003, scientists tried to clone the extinct Pyrenean ibex (C. p. pyrenaica). This attempt failed: of the 285 embryos reconstructed, 54 were transferred to 12 Spanish ibexes and ibex–domestic goat hybrids, but only two survived the initial two months of gestation before they, too, died. In 2009, a second attempt was made to clone the Pyrenean ibex: one clone was born alive, but died seven minutes later, due to physical defects in the lungs.