American philosophy is the activity, corpus, and tradition of philosophers affiliated with the United States. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes that while it lacks a "core of defining features, American Philosophy can nevertheless be seen as both reflecting and shaping collective American identity over the history of the nation."

17th century

The American philosophical tradition began at the time of the European colonization of the New World. The Puritans arrival in New England set the earliest American philosophy into the religious tradition (Puritan Providentialism), and there was also an emphasis on the relationship between the individual and the community. This is evident by the early colonial documents such as the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut (1639) and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641).

Thinkers such as John Winthrop emphasized the public life over the private. Holding that the former takes precedence over the latter, while other writers, such as Roger Williams (co-founder of Rhode Island) held that religious tolerance was more integral than trying to achieve religious homogeneity in a community.

18th century

18th-century American philosophy may be broken into two halves, the first half being marked by the theology of Reformed Puritan Calvinism influenced by the Great Awakening as well as Enlightenment natural philosophy, and the second by the native moral philosophy of the American Enlightenment taught in American colleges. They were used "in the tumultuous years of the 1750s and 1770s" to "forge a new intellectual culture for the United states", which led to the American incarnation of the European Enlightenment that is associated with the political thought of the Founding Fathers.

The 18th century saw the introduction of Francis Bacon and the Enlightenment philosophers Descartes, Newton, Locke, Wollaston, and Berkeley to Colonial British America. Two native-born Americans, Samuel Johnson and Jonathan Edwards, were first influenced by these philosophers; they then adapted and extended their Enlightenment ideas to develop their own American theology and philosophy. Both were originally ordained Puritan Congregationalist ministers who embraced much of the new learning of the Enlightenment. Both were Yale educated and Berkeley influenced idealists who became influential college presidents. Both were influential in the development of American political philosophy and the works of the Founding Fathers. But Edwards based his reformed Puritan theology on Calvinist doctrine, while Johnson converted to the Anglican episcopal religion (the Church of England), then based his new American moral philosophy on William Wollaston's Natural Religion. Late in the century, Scottish innate or common sense realism replaced the native schools of these two rivals in the college philosophy curricula of American colleges; it would remain the dominant philosophy in American academia up to the Civil War.

Introduction of the Enlightenment into America

The first 100 years or so of college education in the American Colonies were dominated in New England by the Puritan theology of William Ames and "the sixteenth-century logical methods of Petrus Ramus." Then in 1714, a donation of 800 books from England, collected by Colonial Agent Jeremiah Dummer, arrived at Yale. They contained what became known as "The New Learning", including "the works of Locke, Descartes, Newton, Boyle, and Shakespeare", and other Enlightenment era authors not known to the tutors and graduates of Puritan Yale and Harvard colleges. They were first opened and studied by an eighteen-year-old graduate student from Guilford, Connecticut, the young American Samuel Johnson, who had also just found and read Lord Francis Bacon's Advancement of Learning. Johnson wrote in his Autobiography, "All this was like a flood of day to his low state of mind" and that "he found himself like one at once emerging out of the glimmer of twilight into the full sunshine of open day." He now considered what he had learned at Yale "nothing but the scholastic cobwebs of a few little English and Dutch systems that would hardly now be taken up in the street."

Johnson was appointed tutor at Yale in 1716. He began to teach the Enlightenment curriculum there, and thus began the American Enlightenment. One of his students for a brief time was a fifteen-year-old Jonathan Edwards. "These two brilliant Yale students of those years, each of whom was to become a noted thinker and college president, exposed the fundamental nature of the problem" of the "incongruities between the old learning and the new." But each had a quite different view on the issues of predestination versus freewill, original sin versus the pursuit of happiness though practicing virtue, and the education of children.

Reformed Calvinism

Jonathan Edwards is considered to be "America's most important and original philosophical theologian." Noted for his energetic sermons, such as "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the First Great Awakening), Edwards emphasized "the absolute sovereignty of God and the beauty of God's holiness." Working to unite Christian Platonism with an empiricist epistemology, with the aid of Newtonian physics, Edwards was deeply influenced by George Berkeley, himself an empiricist, and Edwards derived his importance of the immaterial for the creation of human experience from Bishop Berkeley.

The non-material mind consists of understanding and will, and it is understanding, interpreted in a Newtonian framework, that leads to Edwards' fundamental metaphysical category of Resistance. Whatever features an object may have, it has these properties because the object resists. Resistance itself is the exertion of God's power, and it can be seen in Newton's laws of motion, where an object is "unwilling" to change its current state of motion; an object at rest will remain at rest and an object in motion will remain in motion.

Though Edwards reformed Puritan theology using Enlightenment ideas from natural philosophy, and Locke, Newton, and Berkeley, he remained a Calvinist and hard determinist. Jonathan Edwards also rejected the freedom of the will, saying that "we can do as we please, but we cannot please as we please." According to Edwards, neither good works nor self-originating faith lead to salvation, but rather it is the unconditional grace of God which stands as the sole arbiter of human fortune.

Enlightenment

While the 17th- and early 18th-century American philosophical tradition was decidedly marked by religious themes and the Reformation reason of Ramus, the 18th century saw more reliance on science and the new learning of the Age of Enlightenment, along with an idealist belief in the perfectibility of human beings through teaching ethics and moral philosophy, laissez-faire economics, and a new focus on political matters.

Samuel Johnson has been called "The Founder of American Philosophy" and the "first important philosopher in colonial America and author of the first philosophy textbook published there". He was interested not only in philosophy and theology, but in theories of education, and in knowledge classification schemes, which he used to write encyclopedias, develop college curricula, and create library classification systems.

Johnson was a proponent of the view that "the essence of true religion is morality", and believed that "the problem of denominationalism" could be solved by teaching a non-denominational common moral philosophy acceptable to all religions. So he crafted one. Johnson's moral philosophy was influenced by Descartes and Locke, but more directly by William Wollaston's Religion of Nature Delineated and the idealist philosopher of George Berkeley, with whom Johnson studied while Berkeley was in Rhode Island between 1729 and 1731. Johnson strongly rejected Calvin's doctrine of Predestination and believed that people were autonomous moral agents endowed with freewill and Lockean natural rights. His fusion philosophy of Natural Religion and Idealism, which has been called "American Practical Idealism", was developed as a series of college textbooks in seven editions between 1731 and 1754. These works, and his dialogue Raphael, or The Genius of the English America, written at the time of the Stamp Act crisis, go beyond his Wollaston and Berkeley influences; Raphael includes sections on economics, psychology, the teaching of children, and political philosophy.

His moral philosophy is defined in his college textbook Elementa Philosophica as "the Art of pursuing our highest Happiness by the practice of virtue". It was promoted by President Thomas Clap of Yale, Benjamin Franklin and Provost William Smith at The Academy and College of Philadelphia, and taught at King's College (now Columbia University), which Johnson founded in 1754. It was influential in its day: it has been estimated that about half of American college students between 1743 and 1776, and over half of the men who contributed to the Declaration of Independence or debated it were connected to Johnson's American Practical Idealism moral philosophy. Three members of the Committee of Five who edited the Declaration of Independence were closely connected to Johnson: his educational partner, promoter, friend, and publisher Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, his King's College student Robert R. Livingston of New York, and his son William Samuel Johnson's legal protegee and Yale treasurer Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Johnson's son William Samuel Johnson was the Chairman of the Committee of Style that wrote the U.S. Constitution: edits to a draft version are in his hand in the Library of Congress.

Founders' political philosophy

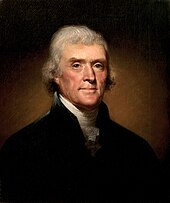

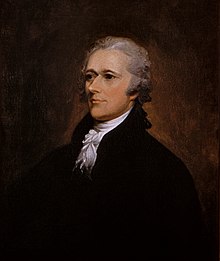

About the time of the Stamp Act, interest rose in civil and political philosophy. Many of the Founding Fathers wrote extensively on political issues, including John Adams, John Dickinson, Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and James Madison. In continuing with the chief concerns of the Puritans in the 17th century, the Founding Fathers debated the interrelationship between God, the state, and the individual. Resulting from this were the United States Declaration of Independence, passed in 1776, and the United States Constitution, ratified in 1788.

The Constitution sets forth a federal and republican form of government that is marked by a balance of powers accompanied by a checks and balances system between the three branches of government: a judicial branch, an executive branch led by the President, and a legislative branch composed of a bicameral legislature where the House of Representatives is the lower house and the Senate is the upper house.

Although the Declaration of Independence does contain references to the Creator, the God of Nature, Divine Providence, and the Supreme Judge of the World, the Founding Fathers were not exclusively theistic. Some professed personal concepts of deism, as was characteristic of other European Enlightenment thinkers, such as Maximilien Robespierre, François-Marie Arouet (better known by his pen name, Voltaire), and Rousseau. However, an investigation of 106 contributors to the Declaration of Independence between September 5, 1774, and July 4, 1776, found that only two men (Franklin and Jefferson), both American Practical Idealists in their moral philosophy, might be called quasi-deists or non-denominational Christians; all the others were publicly members of denominational Christian churches. Even Franklin professed the need for a "public religion" and would attend various churches from time to time. Jefferson was vestryman at the evangelical Calvinistical Reformed Church of Charlottesville, Virginia, a church he himself founded and named in 1777, suggesting that at this time of life he was rather strongly affiliated with a denomination and that the influence of Whitefield and Edwards reached even into Virginia. But the founders who studied or embraced Johnson, Franklin, and Smith's non-denominational moral philosophy were at least influenced by the deistic tendencies of Wollaston's Natural Religion, as evidenced by "the Laws of Nature, and Nature's God" and "the pursuit of Happiness" in the Declaration.

An alternate moral philosophy to the domestic American Practical Idealism, called variously Scottish Innate Sense moral philosophy (by Jefferson), Scottish Commonsense Philosophy, or Scottish common sense realism, was introduced into American Colleges in 1768 by John Witherspoon, a Scottish immigrant and educator who was invited to be President of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). He was a Presbyterian minister and a delegate who joined the Continental Congress just days before the Declaration was debated. His moral philosophy was based on the work of the Scottish philosopher Francis Hutcheson, who also influenced John Adams. When President Witherspoon arrived at the College of New Jersey in 1768, he expanded its natural philosophy offerings, purged the Berkeley adherents from the faculty, including Jonathan Edwards, Jr., and taught his own Hutcheson-influenced form of Scottish innate sense moral philosophy. Some revisionist commentators, including Garry Wills' Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, claimed in the 1970s that this imported Scottish philosophy was the basis for the founding documents of America. However, other historians have questioned this assertion. Ronald Hamowy published a critique of Garry Wills's Inventing America, concluding that "the moment [Wills's] statements are subjected to scrutiny, they appear a mass of confusions, uneducated guesses, and blatant errors of fact." Another investigation of all of the contributors to the United States Declaration of Independence suggests that only Jonathan Witherspoon and John Adams embraced the imported Scottish morality. While Scottish innate sense realism would in the decades after the Revolution become the dominate moral philosophy in classrooms of American academia for almost 100 years, it was not a strong influence at the time of the Declaration was crafted. Johnson's American Practical Idealism and Edwards' Reform Puritan Calvinism were far stronger influences on the men of the Continental Congress and on the Declaration.

Thomas Paine, the English intellectual, pamphleteer, and revolutionary who wrote Common Sense and Rights of Man was an influential promoter of Enlightenment political ideas in America, though he was not a philosopher. Common Sense, which has been described as "the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era", provides justification for the American revolution and independence from the British Crown. Though popular in 1776, historian Pauline Maier cautions that, "Paine's influence was more modest than he claimed and than his more enthusiastic admirers assume."

In summary, "in the middle eighteenth century," it was "the collegians who studied" the ideas of the new learning and moral philosophy taught in the Colonial colleges who "created new documents of American nationhood." It was the generation of "Founding Grandfathers", men such as President Samuel Johnson, President Jonathan Edwards, President Thomas Clap, Benjamin Franklin, and Provost William Smith, who "first created the idealistic moral philosophy of 'the pursuit of Happiness', and then taught it in American colleges to the generation of men who would become the Founding Fathers."

19th century

The 19th century saw the rise of Romanticism in America. The American incarnation of Romanticism was transcendentalism and it stands as a major American innovation. The 19th century also saw the rise of the school of pragmatism, along with a smaller, Hegelian philosophical movement led by George Holmes Howison that was focused in St. Louis, though the influence of American pragmatism far outstripped that of the small Hegelian movement.

Other reactions to materialism included the "Objective idealism" of Josiah Royce, and the "Personalism," sometimes called "Boston personalism," of Borden Parker Bowne.

Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism in the United States was marked by an emphasis on subjective experience, and can be viewed as a reaction against modernism and intellectualism in general and the mechanistic, reductionistic worldview in particular. Transcendentalism is marked by the holistic belief in an ideal spiritual state that 'transcends' the physical and empirical, and this perfect state can only be attained by one's own intuition and personal reflection, as opposed to either industrial progress and scientific advancement or the principles and prescriptions of traditional, organized religion. The most notable transcendentalist writers include Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller.

The transcendentalist writers all desired a deep return to nature, and believed that real, true knowledge is intuitive and personal and arises out of personal immersion and reflection in nature, as opposed to scientific knowledge that is the result of empirical sense experience.

Things such as scientific tools, political institutions, and the conventional rules of morality as dictated by traditional religion need to be transcended. This is found in Henry David Thoreau's Walden; or, Life in the Woods where transcendence is achieved through immersion in nature and the distancing of oneself from society.

Darwinism in America

The release of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory in his 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species had a strong impact on American philosophy. John Fiske and Chauncey Wright both wrote about and argued for the re-conceiving of philosophy through an evolutionary lens. They both wanted to understand morality and the mind in Darwinian terms, setting a precedent for evolutionary psychology and evolutionary ethics.

Darwin's biological theory was also integrated into the social and political philosophies of English thinker Herbert Spencer and American philosopher William Graham Sumner. Herbert Spencer, who coined the oft-misattributed term "survival of the fittest," believed that societies were in a struggle for survival, and that groups within society are where they are because of some level of fitness. This struggle is beneficial to human kind, as in the long run the weak will be weeded out and only the strong will survive. This position is often referred to as Social Darwinism, though it is distinct from the eugenics movements with which social darwinism is often associated. The laissez-faire beliefs of Sumner and Spencer do not advocate coercive breeding to achieve a planned outcome.

Sumner, much influenced by Spencer, believed along with the industrialist Andrew Carnegie that the social implication of the fact of the struggle for survival is that laissez-faire capitalism is the natural political-economic system and is the one that will lead to the greatest amount of well-being. William Sumner, in addition to his advocacy of free markets, also espoused anti-imperialism (having been credited with coining the term "ethnocentrism"), and advocated for the gold standard.

Pragmatism

Perhaps the most influential school of thought that is uniquely American is pragmatism. It began in the late nineteenth century in the United States with Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. Pragmatism begins with the idea that belief is that upon which one is willing to act. It holds that a proposition's meaning is the consequent form of conduct or practice that would be implied by accepting the proposition as true.

Charles Sanders Peirce

Polymath, logician, mathematician, philosopher, and scientist Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) coined the term "pragmatism" in the 1870s. He was a member of The Metaphysical Club, which was a conversational club of intellectuals that also included Chauncey Wright, future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and another early figure of pragmatism, William James. In addition to making profound contributions to semiotics, logic, and mathematics, Peirce wrote what are considered to be the founding documents of pragmatism, "The Fixation of Belief" (1877) and "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878).

In "The Fixation of Belief" Peirce argues for the superiority of the scientific method in settling belief on theoretical questions. In "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" Peirce argued for pragmatism as summed up in that which he later called the pragmatic maxim: "Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object". Peirce emphasized that a conception is general, such that its meaning is not a set of actual, definite effects themselves. Instead the conception of an object is equated to a conception of that object's effects to a general extent of their conceivable implications for informed practice. Those conceivable practical implications are the conception's meaning.

The maxim is intended to help fruitfully clarify confusions caused, for example, by distinctions that make formal but not practical differences. Traditionally one analyzes an idea into parts (his example: a definition of truth as a sign's correspondence to its object). To that needful but confined step, the maxim adds a further and practice-oriented step (his example: a definition of truth as sufficient investigation's destined end).

It is the heart of his pragmatism as a method of experimentational mental reflection arriving at conceptions in terms of conceivable confirmatory and disconfirmatory circumstances—a method hospitable to the formation of explanatory hypotheses, and conducive to the use and improvement of verification. Typical of Peirce is his concern with inference to explanatory hypotheses as outside the usual foundational alternative between deductivist rationalism and inductivist empiricism, though he himself was a mathematician of logic and a founder of statistics.

Peirce's philosophy includes a pervasive three-category system, both fallibilism and anti-skeptical belief that truth is discoverable and immutable, logic as formal semiotic (including semiotic elements and classes of signs, modes of inference, and methods of inquiry along with pragmatism and critical common-sensism), Scholastic realism, theism, objective idealism, and belief in the reality of continuity of space, time, and law, and in the reality of absolute chance, mechanical necessity, and creative love as principles operative in the cosmos and as modes of its evolution.

William James

William James (1842–1910) was "an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy." He is famous as the author of The Varieties of Religious Experience, his monumental tome The Principles of Psychology, and his lecture "The Will to Believe."

James, along with Peirce, saw pragmatism as embodying familiar attitudes elaborated into a radical new philosophical method of clarifying ideas and thereby resolving dilemmas. In his 1910 Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, James paraphrased Peirce's pragmatic maxim as follows:

[T]he tangible fact at the root of all our thought-distinctions, however subtle, is that there is no one of them so fine as to consist in anything but a possible difference of practice. To attain perfect clearness in our thoughts of an object, then, we need only consider what conceivable effects of a practical kind the object may involve — what sensations we are to expect from it, and what reactions we must prepare.

He then went on to characterize pragmatism as promoting not only a method of clarifying ideas but also as endorsing a particular theory of truth. Peirce rejected this latter move by James, preferring to describe the pragmatic maxim only as a maxim of logic and pragmatism as a methodological stance, explicitly denying that it was a substantive doctrine or theory about anything, truth or otherwise.

James is also known for his radical empiricism which holds that relations between objects are as real as the objects themselves. James was also a pluralist in that he believed that there may actually be multiple correct accounts of truth. He rejected the correspondence theory of truth and instead held that truth involves a belief, facts about the world, other background beliefs, and future consequences of those beliefs. Later in his life James would also come to adopt neutral monism, the view that the ultimate reality is of one kind, and is neither mental nor physical.

John Dewey

John Dewey (1859–1952), while still engaging in the lofty academic philosophical work of James and Peirce before him, also wrote extensively on political and social matters, and his presence in the public sphere was much greater than his pragmatist predecessors. In addition to being one of the founding members of pragmatism, John Dewey was one of the founders of functional psychology and was a leading figure of the progressive movement in U.S. schooling during the first half of the 20th century.

Dewey argued against the individualism of classical liberalism, asserting that social institutions are not "means for obtaining something for individuals. They are means for creating individuals." He held that individuals are not things that should be accommodated by social institutions, instead, social institutions are prior to and shape the individuals. These social arrangements are a means of creating individuals and promoting individual freedom.

Dewey is well known for his work in the applied philosophy of the philosophy of education. Dewey's philosophy of education is one where children learn by doing. Dewey believed that schooling was unnecessarily long and formal, and that children would be better suited to learn by engaging in real-life activities. For example, in math, students could learn by figuring out proportions in cooking or seeing how long it would take to travel distances with certain modes of transportation.

20th century

Pragmatism, which began in the 19th century in America, by the beginning of the 20th century began to be accompanied by other philosophical schools of thought, and was eventually eclipsed by them, though only temporarily. The 20th century saw the emergence of process philosophy, itself influenced by the scientific world-view and Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. The middle of the 20th century was witness to the increase in popularity of the philosophy of language and analytic philosophy in America. Existentialism and phenomenology, while very popular in Europe in the 20th century, never achieved the level of popularity in America as they did in continental Europe.

Rejection of idealism

Pragmatism continued its influence into the 20th century, and Spanish-born philosopher George Santayana was one of the leading proponents of pragmatism and realism in this period. He held that idealism was an outright contradiction and rejection of common sense. He held that, if something must be certain in order to be knowledge, then it seems no knowledge may be possible, and the result will be skepticism. According to Santayana, knowledge involved a sort of faith, which he termed "animal faith".

In his book Scepticism and Animal Faith he asserts that knowledge is not the result of reasoning. Instead, knowledge is what is required in order to act and successfully engage with the world. As a naturalist, Santayana was a harsh critic of epistemological foundationalism. The explanation of events in the natural world is within the realm of science, while the meaning and value of this action should be studied by philosophers. Santayana was accompanied in the intellectual climate of 'common sense' philosophy by the thinkers of the New Realism movement, such as Ralph Barton Perry.

Santayana was at one point aligned with early 20th-century American proponents of critical realism—such as Roy Wood Sellars—who were also critics of idealism, but Sellars later concluded that Santayana and Charles Augustus Strong were closer to new realism in their emphasis on veridical perception, whereas Sellars and Arthur O. Lovejoy and James Bissett Pratt were more properly counted among the critical realists who emphasized "the distinction between intuition and denotative characterization".

Process philosophy

Process philosophy embraces the Einsteinian world-view, and its main proponents include Alfred North Whitehead and Charles Hartshorne. The core belief of process philosophy is the claim that events and processes are the principal ontological categories. Whitehead asserted in his book The Concept of Nature that the things in nature, what he referred to as "concresences" are a conjunction of events that maintain a permanence of character. Process philosophy is Heraclitan in the sense that a fundamental ontological category is change. Charles Hartshorne was also responsible for developing the process philosophy of Whitehead into process theology.

Analytic philosophy

The middle of the 20th century was the beginning of the dominance of analytic philosophy in America. Analytic philosophy, prior to its arrival in America, had begun in Europe with the work of Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and the logical positivists. According to logical positivism, the truths of logic and mathematics are tautologies, and those of science are empirically verifiable. Any other claim, including the claims of ethics, aesthetics, theology, metaphysics, and ontology, are meaningless (this theory is called verificationism). With the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, many positivists fled Germany to Britain and America, and this helped reinforce the dominance of analytic philosophy in the United States in subsequent years.

W.V.O. Quine, while not a logical positivist, shared their view that philosophy should stand shoulder to shoulder with science in its pursuit of intellectual clarity and understanding of the world. He criticized the logical positivists and the analytic/synthetic distinction of knowledge in his essay "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" and advocated for his "web of belief," which is a coherentist theory of justification. In Quine's epistemology, since no experiences occur in isolation, there is actually a holistic approach to knowledge where every belief or experience is intertwined with the whole. Quine is also famous for inventing the term "gavagai" as part of his theory of the indeterminacy of translation.

Saul Kripke, a student of Quine at Harvard, has profoundly influenced analytic philosophy. Kripke was ranked among the top ten most important philosophers of the past 200 years in a poll conducted by Brian Leiter (Leiter Reports: a Philosophy Blog; open access poll) Kripke is best known for four contributions to philosophy: (1) Kripke semantics for modal and related logics, published in several essays beginning while he was still in his teens. (2) His 1970 Princeton lectures Naming and Necessity (published in 1972 and 1980), that significantly restructured the philosophy of language and, as some have put it, "made metaphysics respectable again". (3) His interpretation of the philosophy of Wittgenstein. (4) His theory of truth. He has also made important contributions to set theory.

David Kellogg Lewis, another student of Quine at Harvard, was ranked as one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century in a poll conducted by Brian Leiter (open access poll). He is well known for his controversial advocacy of modal realism, the position which holds that there is an infinite number of concrete and causally isolated possible worlds, of which ours is one. These possible worlds arise in the field of modal logic.

Thomas Kuhn was an important philosopher and writer who worked extensively in the fields of the history of science and the philosophy of science. He is famous for writing The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, one of the most cited academic works of all time. The book argues that science proceeds through different paradigms as scientists find new puzzles to solve. There follows a widespread struggle to find answers to questions, and a shift in world views occurs, which is referred to by Kuhn as a paradigm shift. The work is considered a milestone in the sociology of knowledge.

Return of political philosophy

The analytic philosophers troubled themselves with the abstract and the conceptual, and American philosophy did not fully return to social and political concerns (that dominated American philosophy at the time of the founding of the United States) until the 1970s.

The return to political and social concerns included the popularity of works of Ayn Rand, who promoted ethical egoism (the praxis of the belief system she called Objectivism) in her novels, The Fountainhead in 1943 and Atlas Shrugged in 1957. These two novels gave birth to the Objectivist movement and would influence a small group of students called The Collective, one of whom was a young Alan Greenspan, a self-described libertarian who would become Chairman of the Federal Reserve. Objectivism holds that there is an objective external reality that can be known with reason, that human beings should act in accordance with their own rational self-interest, and that the proper form of economic organization is laissez-faire capitalism. Some academic philosophers have been highly critical of the quality and intellectual rigor of Rand's work, but she remains a popular, albeit controversial, figure within the American libertarian movement.

In 1971 John Rawls published his book A Theory of Justice. The book puts forth Rawls' view of justice as fairness, a version of social contract theory. Rawls employs a conceptual mechanism called the veil of ignorance to outline his idea of the original position. In Rawls' philosophy, the original position is the correlate to the Hobbesian state of nature. While in the original position, persons are said to be behind the veil of ignorance, which makes these persons unaware of their individual characteristics and their place in society, such as their race, religion, wealth, etc. The principles of justice are chosen by rational persons while in this original position. The two principles of justice are the equal liberty principle and the principle which governs the distribution of social and economic inequalities. From this, Rawls argues for a system of distributive justice in accordance with the Difference Principle, which says that all social and economic inequalities must be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged.

Viewing Rawls as promoting excessive government control and rights violations, libertarian Robert Nozick published Anarchy, State, and Utopia in 1974. The book advocates for a minimal state and defends the liberty of the individual. He argues that the role of government should be limited to "police protection, national defense, and the administration of courts of law, with all other tasks commonly performed by modern governments – education, social insurance, welfare, and so forth – taken over by religious bodies, charities, and other private institutions operating in a free market."

Nozick asserts his view of the entitlement theory of justice, which says that if everyone in society has acquired their holdings in accordance with the principles of acquisition, transfer, and rectification, then any pattern of allocation, no matter how unequal the distribution may be, is just. The entitlement theory of justice holds that the "justice of a distribution is indeed determined by certain historical circumstances (contrary to end-state theories), but it has nothing to do with fitting any pattern guaranteeing that those who worked the hardest or are most deserving have the most shares."

Alasdair MacIntyre, while he was born and educated in the United Kingdom, has spent around forty years living and working in the United States. He is responsible for the resurgence of interest in virtue ethics, a moral theory first propounded by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. A prominent Thomist political philosopher, he holds that "modern philosophy and modern life are characterized by the absence of any coherent moral code, and that the vast majority of individuals living in this world lack a meaningful sense of purpose in their lives and also lack any genuine community". He recommends a return to genuine political communities where individuals can properly acquire their virtues.

Outside academic philosophy, political and social concerns took center stage with the Civil Rights Movement and the writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. King was an American Christian minister and activist known for advancing civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience.

Feminism

While there were earlier writers who would be considered feminist, such as Sarah Grimké, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Anne Hutchinson, the feminist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, also known as second-wave feminism, is notable for its impact in philosophy.

The popular mind was taken with Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique. This was accompanied by other feminist philosophers, such as Alicia Ostriker and Adrienne Rich. These philosophers critiqued basic assumptions and values like objectivity and what they believe to be masculine approaches to ethics, such as rights-based political theories. They maintained there is no such thing as a value-neutral inquiry and they sought to analyze the social dimensions of philosophical issues.

Contemporary philosophy

Towards the end of the 20th century there was a resurgence of interest in pragmatism. Largely responsible for this are Hilary Putnam and Richard Rorty. Rorty is famous as the author of Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature and Philosophy and Social Hope. Hilary Putnam is well known for his quasi-empiricism in mathematics, his challenge of the brain in a vat thought experiment, and his other work in philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and philosophy of science.

The debates that occur within the philosophy of mind have taken center stage. American philosophers such as Hilary Putnam, Donald Davidson, Daniel Dennett, Douglas Hofstadter, John Searle, as well as Patricia and Paul Churchland continue the discussion of such issues as the nature of mind and the hard problem of consciousness, a philosophical problem indicated by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers.

In the early 21st century, embodied cognition has gained strength as a theory of mind-body-world integration. Philosophers such as Shaun Gallagher and Alva Noë, together with British philosophers such as Andy Clark defend this view, seeing it as a natural development of pragmatism, and of the thinking of Kant, Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty among others.

Noted American legal philosophers Ronald Dworkin and Richard Posner work in the fields of political philosophy and jurisprudence. Posner is famous for his economic analysis of law, a theory which uses microeconomics to understand legal rules and institutions. Dworkin is famous for his theory of law as integrity and legal interpretivism, especially as presented in his book Law's Empire.

Philosopher Cornel West is known for his analysis of American cultural life with regards to race, gender, and class issues, as well as his associations with pragmatism and transcendentalism.

Alvin Plantinga is a Christian analytic philosopher known for his free will defense with respect to the logical problem of evil, the evolutionary argument against naturalism, the position that belief in the existence of God is properly basic, and his modal version of the ontological argument for the existence of Yahweh. Michael C. Rea has developed Plantinga's thought by claiming that both naturalism and supernaturalism are research programmes that have to be adopted as a basis for research.