| |

screensaver with custom background | |

| Developer(s) | University of California, Berkeley |

|---|---|

| Initial release | May 17, 1999 |

| Stable release | SETI@home v8:8.00 / December 30, 2015

SETI@home v8 for NVIDIA and AMD/ATi GPU Card:8.12/ April 23, 2015 |

| Development status | In hibernation |

| Project goal(s) | Discovery of radio evidence of extraterrestrial life |

| Funding | Public funding and private donations |

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows, Linux, Android, macOS, Solaris, IBM AIX, FreeBSD, DragonflyBSD, OpenBSD, NetBSD, HP-UX, IRIX, Tru64 Unix, OS/2 Warp, eComStation |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Type | Volunteer computing |

| License | GPL |

| Active users | |

| Total users | |

| Active hosts | 144,779 (March 2020) |

| Total hosts | 165,178 (March 2020) |

| Website | setiathome |

SETI@home ("SETI at home") is a project of the Berkeley SETI Research Center to analyze radio signals with the aim of searching for signs of extraterrestrial intelligence. Until March 2020, it was run as an Internet-based public volunteer computing project that employed the BOINC software platform. It is hosted by the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, and is one of many activities undertaken as part of the worldwide SETI effort.

SETI@home software was released to the public on May 17, 1999, making it the third large-scale use of volunteer computing over the Internet for research purposes, after Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search (GIMPS) was launched in 1996 and distributed.net in 1997. Along with MilkyWay@home and Einstein@home, it is the third major computing project of this type that has the investigation of phenomena in interstellar space as its primary purpose.

In March 2020, the project stopped sending out new work to SETI@home users, bringing the crowdsourced computing aspect of the project to a stop. At the time, the team intended to shift focus onto the analysis and interpretation of the 20 years' worth of accumulated data. However, the team left open the possibility of eventually resuming volunteer computing using data from other radio telescopes, such as MeerKAT and FAST.

As of November 2021, the science team has analysed the data and removed noisy signals (Radio Frequency Interference) using the Nebula tool they developed and will choose the top-scoring 100 or so multiplets to be observed using the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, to which they have been granted 24 hours of observation time.

Scientific research

The two original goals of SETI@home were:

- to do useful scientific work by supporting an observational analysis to detect intelligent life outside Earth

- to prove the viability and practicality of the "volunteer computing" concept

The second of these goals is considered to have succeeded completely. The current BOINC environment, a development of the original SETI@home, is providing support for many computationally intensive projects in a wide range of disciplines.

The first of these goals has to date yielded no conclusive results: no evidence for ETI signals has been shown via SETI@home. However, the ongoing continuation is predicated on the assumption that the observational analysis is not "ill-posed." The remainder of this article deals specifically with the original SETI@home observations/analysis. The vast majority of the sky (over 98%) has yet to be surveyed, and each point in the sky must be surveyed many times to exclude even a subset of possibilities.

Procedure details

SETI@home searches for possible evidence of radio transmissions from extraterrestrial intelligence using observational data from the Arecibo radio telescope and the Green Bank Telescope. The data is taken "piggyback" or "passively" while the telescope is used for other scientific programs. The data is digitized, stored, and sent to the SETI@home facility. The data is then parsed into small chunks in frequency and time, and analyzed, using software, to search for any signals—that is, variations which cannot be ascribed to noise, and hence contain information. Using volunteer computing, SETI@home sends the millions of chunks of data to be analyzed off-site by home computers, and then have those computers report the results. Thus what appears a difficult problem in data analysis is reduced to a reasonable one by aid from a large, Internet-based community of borrowed computer resources.

The software searches for five types of signals that distinguish them from noise:

- Spikes in power spectra

- Gaussian rises and falls in transmission power, possibly representing the telescope beam's main lobe passing over a radio source

- Triplets – three power spikes in a row

- Pulsing signals that possibly represent a narrowband digital-style transmission

- Autocorrelation detects signal waveforms.

There are many variations on how an ETI signal may be affected by the interstellar medium, and by the relative motion of its origin compared to Earth. The potential "signal" is thus processed in many ways (although not testing all detection methods nor scenarios) to ensure the highest likelihood of distinguishing it from the scintillating noise already present in all directions of outer space. For instance, another planet is very likely to be moving at a speed and acceleration with respect to Earth, and that will shift the frequency, over time, of the potential "signal." Checking for this through processing is done, to an extent, in the SETI@home software.

The process is somewhat like tuning a radio to various channels, and looking at the signal strength meter. If the strength of the signal goes up, that gets attention. More technically, it involves a lot of digital signal processing, mostly discrete Fourier transforms at various chirp rates and durations.

Results

To date, the project has not confirmed the detection of any ETI signals. However, it has identified several candidate targets (sky positions), where the spike in intensity is not easily explained as noise spots, for further analysis. The most significant candidate signal to date was announced on September 1, 2004, named Radio source SHGb02+14a.

While the project has not reached the stated primary goal of finding extraterrestrial intelligence, it has proved to the scientific community that volunteer computing projects using Internet-connected computers can succeed as a viable analysis tool, and even beat the largest supercomputers. However, it has not been demonstrated that the order of magnitude excess in computers used, many outside the home (the original intent was to use 50,000–100,000 "home" computers), has benefited the project scientifically. (For more on this, see § Challenges below.)

Astronomer Seth Shostak stated in 2004 that he expects to get a conclusive signal and proof of alien contact between 2020 and 2025, based on the Drake equation. This implies that a prolonged effort may benefit SETI@home, despite its (present) twenty-year run without success in ETI detection.

Technology

Anybody with an at least intermittently Internet-connected computer was able to participate in SETI@home by running a free program that downloaded and analyzed radio telescope data.

Observational data were recorded on 2-terabyte SATA hard disk drives fed from the Arecibo Telescope in Puerto Rico, each holding about 2.5 days of observations, which were then sent to Berkeley. Arecibo does not have a broadband Internet connection, so data must go by postal mail to Berkeley. Once there, it is divided in both time and frequency domains work units of 107 seconds of data, or approximately 0.35 megabytes (350 kilobytes or 350,000 bytes), which overlap in time but not in frequency. These work units are then sent from the SETI@home server over the Internet to personal computers around the world to analyze.

Data was merged into a database using SETI@home computers in Berkeley. Interference was rejected, and various pattern-detection algorithms were applied to search for the most interesting signals.

The project used CUDA for GPU processing starting in 2015.

In 2016 SETI@home began processing data from the Breakthrough Listen project.

Software

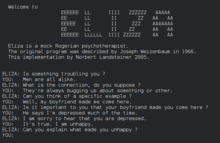

The SETI@home volunteer computing software ran either as a screensaver or continuously while a user worked, making use of processor time that would otherwise be unused.

The initial software platform, now referred to as "SETI@home Classic", ran from May 17, 1999, to December 15, 2005. This program was only capable of running SETI@home; it was replaced by Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC), which also allows users to contribute to other volunteer computing projects at the same time as running SETI@home. The BOINC platform also allowed testing for more types of signals.

The discontinuation of the SETI@home Classic platform rendered older Macintosh computers running the classic Mac OS (pre December, 2001) unsuitable for participating in the project.

SETI@home was available for the Sony PlayStation 3 console.

On May 3, 2006, new work units for a new version of SETI@home called "SETI@home Enhanced" started distribution. Since computers had the power for more computationally intensive work than when the project began, this new version was more sensitive by a factor of two concerning Gaussian signals and to some kinds of pulsed signals than the original SETI@home (BOINC) software. This new application had been optimized to the point where it would run faster on some work units than earlier versions. However, some work units (the best work units, scientifically speaking) would take significantly longer.

In addition, some distributions of the SETI@home applications were optimized for a particular type of CPU. They were referred to as "optimized executables", and had been found to run faster on systems specific for that CPU. As of 2007, most of these applications were optimized for Intel processors and their corresponding instruction sets.

The results of the data processing were normally automatically transmitted when the computer was next connected to the Internet; it could also be instructed to connect to the Internet as needed.

Statistics

With over 5.2 million participants worldwide, the project was the volunteer computing project with the most participants to date. The original intent of SETI@home was to utilize 50,000–100,000 home computers. Since its launch on May 17, 1999, the project has logged over two million years of aggregate computing time. On September 26, 2001, SETI@home had performed a total of 1021 floating point operations. It was acknowledged by the 2008 edition of the Guinness World Records as the largest computation in history. With over 145,000 active computers in the system (1.4 million total) in 233 countries, as of 23 June 2013, SETI@home had the ability to compute over 668 teraFLOPS. For comparison, the Tianhe-2 computer, which as of 23 June 2013 was the world's fastest supercomputer, was able to compute 33.86 petaFLOPS (approximately 50 times greater).

Project future

There were plans to get data from the Parkes Observatory in Australia to analyze the southern hemisphere. However, as of 3 June 2018, these plans were not mentioned in the project's website. Other plans include a Multi-Beam Data Recorder, a Near Time Persistency Checker and Astropulse (an application that uses coherent dedispersion to search for pulsed signals). Astropulse will team with the original SETI@home to detect other sources, such as rapidly rotating pulsars, exploding primordial black holes, or as-yet unknown astrophysical phenomena. Beta testing of the final public release version of Astropulse was completed in July 2008, and the distribution of work units to higher spec machines capable of processing the more CPU intensive work units started in mid-July 2008.

On March 31, 2020, UC Berkeley stopped sending out new data for SETI@Home clients to process, ending the effort for the time being. The program stated they were at a point of "diminishing returns" with the volunteer processing and needed to put the effort into hibernation while they processed the results.

Competitive aspect

SETI@home users quickly started to compete with one another to process the maximum number of work units. Teams were formed to combine the efforts of individual users. The competition continued and grew larger with the introduction of BOINC.

As with any competition, attempts have been made to "cheat" the system and claim credit for work that has not been performed. To combat cheats, the SETI@home system sends every work unit to multiple computers, a value known as "initial replication" (currently 2). Credit is only granted for each returned work unit once a minimum number of results have been returned and the results agree, a value known as "minimum quorum" (currently 2). If, due to computation errors or cheating by submitting false data, not enough results agree, more identical work units are sent out until the minimum quorum can be reached. The final credit granted to all machines which returned the correct result is the same and is the lowest of the values claimed by each machine.

Some users have installed and run SETI@home on computers at their workplaces; an act known as "Borging", after the assimilation-driven Borg of Star Trek. In some cases, SETI@home users have misused company resources to gain work-unit results with at least two individuals getting fired for running SETI@home on an enterprise production system. There is a thread in the newsgroup alt.sci.seti which bears the title "Anyone fired for SETI screensaver" and ran starting as early as September 14, 1999.

Other users collect large quantities of equipment together at home to create "SETI farms", which typically consist of a number of computers consisting of only a motherboard, CPU, RAM and power supply that are arranged on shelves as diskless workstations running either Linux or old versions of Microsoft Windows "headless" (without a monitor).

Challenges

Closure of Arecibo Observatory

Until 2020, SETI@home procured its data from the Arecibo Observatory facility that was operated by the National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center and administered by SRI International.

The decreasing operating budget for the observatory has created a shortfall of funds which has not been made up from other sources such as private donors, NASA, other foreign research institutions, nor private non-profit organizations such as SETI@home.

However, in the overall long-term views held by many involved with the SETI project, any usable radio telescope could take over from Arecibo (which completely collapsed in December 2020), as all the SETI systems are portable and relocatable.

More restrictive computer use policies in businesses

In one documented case, an individual was fired for explicitly importing and using the SETI@home software on computers used for the U.S. state of Ohio. In another incident a school IT director resigned after his installation allegedly cost his school district $1 million in removal costs; however, other reasons for this firing included lack of communication with his superiors, not installing firewall software and alleged theft of computer equipment, leading a ZDNet editor to comment that "the volunteer computing nonsense was simply the best and most obvious excuse the district had to terminate his contract with cause".

As of 16 October 2005, approximately one-third of the processing for the non-BOINC version of the software was performed on work or school based machines. As many of these computers will give reduced privileges to ordinary users, it is possible that much of this has been done by network administrators.

To some extent, this may be offset by better connectivity to home machines and increasing performance of home computers, especially those with GPUs, which have also benefited other volunteer computing projects such as Folding@Home. The spread of mobile computing devices provides another large resource for volunteer computing. For example, in 2012, Piotr Luszczek (a former doctoral student of Jack Dongarra) presented results showing that an iPad 2 matched the historical performance of a Cray-2 (the fastest computer in the world in 1985) on an embedded LINPACK benchmark.

Funding

There is currently no government funding for SETI research, and private funding is always limited. Berkeley Space Science Lab has found ways of working with small budgets, and the project has received donations allowing it to go well beyond its original planned duration, but it still has to compete for limited funds with other SETI projects and other space sciences projects.

In a December 16, 2007 plea for donations, SETI@home stated its present modest state and urged donations of $476,000 needed for continuation into 2008.

Unofficial clients

A number of individuals and companies made unofficial changes to the distributed part of the software to try to produce faster results, but this compromised the integrity of all the results. As a result, the software had to be updated to make it easier to detect such changes, and discover unreliable clients. BOINC will run on unofficial clients; however, clients that return different and therefore incorrect data are not allowed, so corrupting the result database is avoided. BOINC relies on cross-checking to validate data but unreliable clients need to be identified, to avoid situations when two of these report the same invalid data and therefore corrupt the database. A very popular unofficial client (lunatic) allows users to take advantage of the special features provided by their processor(s) such as SSE, SSE2, SSE3, SSSE3, SSE4.1, and AVX to allow for faster processing.

Hardware and database failures

SETI@home is a test bed for further development not only of BOINC but of other hardware and software (database) technology. Under SETI@home processing loads, these experimental technologies can be more challenging than expected, as SETI databases do not have typical accounting and business data or relational structures. The non-traditional database uses often do incur greater processing overheads and risk of database corruption and outright database failure. Hardware, software and database failures can (and do) cause dips in project participation.

The project has had to shut down several times to change over to new databases capable of handling more massive datasets. Hardware failure has proven to be a substantial source of project shutdowns, as hardware failure is often coupled with database corruption.