Synergy is an interaction or cooperation giving rise to a whole that is greater than the simple sum of its parts (i.e., a non-linear addition of force, energy, or effect). The term synergy comes from the Attic Greek word συνεργία synergia from synergos, συνεργός, meaning "working together". Synergy is similar in concept to emergence.

History

The words synergy and synergetic have been used in the field of physiology since at least the middle of the 19th century:

SYN'ERGY, Synergi'a, Synenergi'a, (F.) Synergie; from συν, 'with', and εργον, 'work'. A correlation or concourse of action between different organs in health; and, according to some, in disease.

- —Dunglison, Robley Medical Lexicon Blanchard and Lea, 1853

In 1896, Henri Mazel applied the term "synergy" to social psychology by writing La synergie sociale, in which he argued that Darwinian theory failed to account of "social synergy" or "social love", a collective evolutionary drive. The highest civilizations were the work not only of the elite but of the masses too; those masses must be led, however, because the crowd, a feminine and unconscious force, cannot distinguish between good and evil.

In 1909, Lester Frank Ward defined synergy as the universal constructive principle of nature:

I have characterized the social struggle as centrifugal and social solidarity as centripetal. Either alone is productive of evil consequences. Struggle is essentially destructive of the social order, while communism removes individual initiative. The one leads to disorder, the other to degeneracy. What is not seen—the truth that has no expounders—is that the wholesome, constructive movement consists in the properly ordered combination and interaction of both these principles. This is social synergy, which is a form of cosmic synergy, the universal constructive principle of nature.

- —Ward, Lester F. Glimpses of the Cosmos, volume VI (1897–1912) G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1918, p. 358

In Christian theology, synergism is the idea that salvation involves some form of cooperation between divine grace and human freedom.

A modern view of synergy in natural sciences derives from the relationship between energy and information. Synergy is manifested when the system makes the transition between the different information (i.e. order, complexity) embedded in both systems.

Abraham Maslow and John Honigmann drew attention to an important development in the cultural anthropology field which arose in lectures by Ruth Benedict from 1941, for which the original manuscripts have been lost but the ideas preserved in "Synergy: Some Notes of Ruth Benedict" (1969).

Descriptions and usages

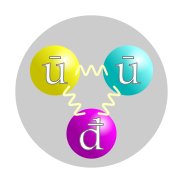

In the natural world, synergistic phenomena are ubiquitous, ranging from physics (for example, the different combinations of quarks that produce protons and neutrons) to chemistry (a popular example is water, a compound of hydrogen and oxygen), to the cooperative interactions among the genes in genomes, the division of labor in bacterial colonies, the synergies of scale in multicellular organisms, as well as the many different kinds of synergies produced by socially-organized groups, from honeybee colonies to wolf packs and human societies: compare stigmergy, a mechanism of indirect coordination between agents or actions that results in the self-assembly of complex systems. Even the tools and technologies that are widespread in the natural world represent important sources of synergistic effects. The tools that enabled early hominins to become systematic big-game hunters is a primordial human example.

In the context of organizational behavior, following the view that a cohesive group is more than the sum of its parts, synergy is the ability of a group to outperform even its best individual member. These conclusions are derived from the studies conducted by Jay Hall on a number of laboratory-based group ranking and prediction tasks. He found that effective groups actively looked for the points in which they disagreed and in consequence encouraged conflicts amongst the participants in the early stages of the discussion. In contrast, the ineffective groups felt a need to establish a common view quickly, used simple decision making methods such as averaging, and focused on completing the task rather than on finding solutions they could agree on. In a technical context, its meaning is a construct or collection of different elements working together to produce results not obtainable by any of the elements alone. The elements, or parts, can include people, hardware, software, facilities, policies, documents: all things required to produce system-level results. The value added by the system as a whole, beyond that contributed independently by the parts, is created primarily by the relationship among the parts, that is, how they are interconnected. In essence, a system constitutes a set of interrelated components working together with a common objective: fulfilling some designated need.

If used in a business application, synergy means that teamwork will produce an overall better result than if each person within the group were working toward the same goal individually. However, the concept of group cohesion needs to be considered. Group cohesion is that property that is inferred from the number and strength of mutual positive attitudes among members of the group. As the group becomes more cohesive, its functioning is affected in a number of ways. First, the interactions and communication between members increase. Common goals, interests and small size all contribute to this. In addition, group member satisfaction increases as the group provides friendship and support against outside threats.

There are negative aspects of group cohesion that have an effect on group decision-making and hence on group effectiveness. There are two issues arising. The risky shift phenomenon is the tendency of a group to make decisions that are riskier than those that the group would have recommended individually. Group Polarisation is when individuals in a group begin by taking a moderate stance on an issue regarding a common value and, after having discussed it, end up taking a more extreme stance.

A second, potential negative consequence of group cohesion is group think. Group think is a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in cohesive group, when the members' striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to appraise realistically the alternative courses of action. Studying the events of several American policy "disasters" such as the failure to anticipate the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (1941) and the Bay of Pigs Invasion fiasco (1961), Irving Janis argued that they were due to the cohesive nature of the committees that made the relevant decisions.

That decisions made by committees lead to failure in a simple system is noted by Dr. Chris Elliot. His case study looked at IEEE-488, an international standard set by the leading US standards body; it led to a failure of small automation systems using the IEEE-488 standard (which codified a proprietary communications standard HP-IB). But the external devices used for communication were made by two different companies, and the incompatibility between the external devices led to a financial loss for the company. He argues that systems will be safe only if they are designed, not if they emerge by chance.

The idea of a systemic approach is endorsed by the United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive. The successful performance of the health and safety management depends upon the analyzing the causes of incidents and accidents and learning correct lessons from them. The idea is that all events (not just those causing injuries) represent failures in control, and present an opportunity for learning and improvement. UK Health and Safety Executive, Successful health and safety management (1997): this book describes the principles and management practices, which provide the basis of effective health and safety management. It sets out the issues that need to be addressed, and can be used for developing improvement programs, self-audit, or self-assessment. Its message is that organizations must manage health and safety with the same degree of expertise and to the same standards as other core business activities, if they are to effectively control risks and prevent harm to people.

The term synergy was refined by R. Buckminster Fuller, who analyzed some of its implications more fully and coined the term synergetics.

- A dynamic state in which combined action is favored over the difference of individual component actions.

- Behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the behavior of their parts taken separately, known as emergent behavior.

- The cooperative action of two or more stimuli (or drugs), resulting in a different or greater response than that of the individual stimuli.

Information theory

Mathematical formalizations of synergy have been proposed using information theory to rigorously define the relationships between "wholes" and "parts". In this context, synergy is said to occur when there is information present in the joint state of multiple variables that cannot be extracted from the individual parts considered individually. For example, consider the logical XOR gate. If for three binary variables, the mutual information between any individual source and the target is 0 bit. However, the joint mutual information bit. There is information about the target that can only be extracted from the joint state of the inputs considered jointly, and not any others.

There is, thus far, no universal agreement on how synergy can best be quantified, with different approaches that decompose information into redundant, unique, and synergistic components appearing in the literature. Despite the lack of universal agreement, information-theoretic approaches to statistical synergy have been applied to diverse fields, including climatology, neuroscience sociology, and machine learning Synergy has also been proposed as a possible foundation on which to build a mathematically robust definition of emergence in complex systems and may be relevant to formal theories of consciousness.

Biological sciences

Synergy of various kinds has been advanced by Peter Corning as a causal agency that can explain the progressive evolution of complexity in living systems over the course of time. According to the Synergism Hypothesis, synergistic effects have been the drivers of cooperative relationships of all kinds and at all levels in living systems. The thesis, in a nutshell, is that synergistic effects have often provided functional advantages (economic benefits) in relation to survival and reproduction that have been favored by natural selection. The cooperating parts, elements, or individuals become, in effect, functional "units" of selection in evolutionary change. Similarly, environmental systems may react in a non-linear way to perturbations, such as climate change, so that the outcome may be greater than the sum of the individual component alterations. Synergistic responses are a complicating factor in environmental modeling.

Pest synergy

Pest synergy would occur in a biological host organism population, where, for example, the introduction of parasite A may cause 10% fatalities, and parasite B may also cause 10% loss. When both parasites are present, the losses would normally be expected to total less than 20%, yet, in some cases, losses are significantly greater. In such cases, it is said that the parasites in combination have a synergistic effect.

Drug synergy

Mechanisms that may be involved in the development of synergistic effects include:

- Effect on the same cellular system (e.g. two different antibiotics like a penicillin and an aminoglycoside; penicillins damage the cell wall of gram-positive bacteria and improve the penetration of aminoglycosides).

- Bioavailability (e.g. ayahuasca (or pharmahuasca) consists of DMT combined with MAOIs that interfere with the action of the MAO enzyme and stop the breakdown of chemical compounds such as DMT).

- Reduced risk for substance abuse (e.g. lisdexamfetamine, which is a combination of the amino acid L-lysine, attached to dextroamphetamine, may have a lower liability for abuse as a recreational drug)

- Increased potency (e.g. as with other NSAIDs, combinations of aspirin and caffeine provide slightly greater pain relief than aspirin alone).

- Prevention or delay of degradation in the body (e.g. the antibiotic Ciprofloxacin inhibits the metabolism of Theophylline).[30]: 931

- Slowdown of excretion (e.g. Probenecid delays the renal excretion of Penicillin and thus prolongs its effect).

- Anticounteractive action: for example, the effect of oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Oxaliplatin intercalates DNA, thereby preventing the cell from replicating DNA. Irinotecan inhibits topoisomerase 1, consequently the cytostatic effect is increased.

- Effect on the same receptor but different sites (e.g. the coadministration of benzodiazepines and barbiturates, both act by enhancing the action of GABA on GABAA receptors, but benzodiazepines increase the frequency of channel opening, whilst barbiturates increase the channel closing time, making these two drugs dramatically enhance GABAergic neurotransmission).

- In addition to the chemical nature of the drug itself, the topology of the chemical reaction network that connect the two targets determines the type of drug-drug interaction.

More mechanisms are described in an exhaustive 2009 review.

Toxicological synergy

Toxicological synergy is of concern to the public and regulatory agencies because chemicals individually considered safe might pose unacceptable health or ecological risk in combination. Articles in scientific and lay journals include many definitions of chemical or toxicological synergy, often vague or in conflict with each other. Because toxic interactions are defined relative to the expectation under "no interaction", a determination of synergy (or antagonism) depends on what is meant by "no interaction". The United States Environmental Protection Agency has one of the more detailed and precise definitions of toxic interaction, designed to facilitate risk assessment. In their guidance documents, the no-interaction default assumption is dose addition, so synergy means a mixture response that exceeds that predicted from dose addition. The EPA emphasizes that synergy does not always make a mixture dangerous, nor does antagonism always make the mixture safe; each depends on the predicted risk under dose addition.

For example, a consequence of pesticide use is the risk of health effects. During the registration of pesticides in the United States exhaustive tests are performed to discern health effects on humans at various exposure levels. A regulatory upper limit of presence in foods is then placed on this pesticide. As long as residues in the food stay below this regulatory level, health effects are deemed highly unlikely and the food is considered safe to consume.

However, in normal agricultural practice, it is rare to use only a single pesticide. During the production of a crop, several different materials may be used. Each of them has had determined a regulatory level at which they would be considered individually safe. In many cases, a commercial pesticide is itself a combination of several chemical agents, and thus the safe levels actually represent levels of the mixture. In contrast, a combination created by the end user, such as a farmer, has rarely been tested in that combination. The potential for synergy is then unknown or estimated from data on similar combinations. This lack of information also applies to many of the chemical combinations to which humans are exposed, including residues in food, indoor air contaminants, and occupational exposures to chemicals. Some groups think that the rising rates of cancer, asthma, and other health problems may be caused by these combination exposures; others have alternative explanations. This question will likely be answered only after years of exposure by the population in general and research on chemical toxicity, usually performed on animals. Examples of pesticide synergists include Piperonyl butoxide and MGK 264.

Human synergy

Synergy exists in individual and social interactions among humans, with some arguing that social cooperation cannot be requires synergy to continue. One way of quantifying synergy in human social groups is via energy use, where larger groups of humans (i.e., cities) use energy more efficiently that smaller groups of humans.

Human synergy can also occur on a smaller scale, like when individuals huddle together for warmth or in workplaces where labor specialization increase efficiencies.

When synergy occurs in the work place, the individuals involved get to work in a positive and supportive working environment. When individuals get to work in environments such as these, the company reaps the benefits. The authors of Creating the Best Workplace on Earth Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones, state that "highly engaged employees are, on average, 50% more likely to exceed expectations that the least-engaged workers. And companies with highly engaged people outperform firms with the most disengaged folks- by 54% in employee retention, by 89% in customer satisfaction, and by fourfold in revenue growth. Also, those that are able to be open about their views on the company, and have confidence that they will be heard, are likely to be a more organized employee who helps his/ her fellow team members succeed.

Human interaction with technology can also increase synergy. Organismic computing is an approach to improving group efficacy by increasing synergy in human groups via technological means.

Theological synergism

In Christian theology, synergism is the belief that salvation involves a cooperation between divine grace and human freedom. Eastern Orthodox theology, in particular, uses the term "synergy" to describe this relationship, drawing on biblical language: "in Paul's words, 'We are fellow-workers (synergoi) with God' (1 Corinthians iii, 9)".

Corporate synergy

Corporate synergy occurs when corporations interact congruently. A corporate synergy refers to a financial benefit that a corporation expects to realize when it merges with or acquires another corporation. This type of synergy is a nearly ubiquitous feature of a corporate acquisition and is a negotiating point between the buyer and seller that impacts the final price both parties agree to. There are distinct types of corporate synergies, as follows.

Marketing

A marketing synergy refers to the use of information campaigns, studies, and scientific discovery or experimentation for research and development. This promotes the sale of products for varied use or off-market sales as well as development of marketing tools and in several cases exaggeration of effects. It is also often a meaningless buzzword used by corporate leaders.

Microsoft Word offers "cooperation" as a refinement suggestion to the word "synergy."

Revenue

A revenue synergy refers to the opportunity of a combined corporate entity to generate more revenue than its two predecessor stand-alone companies would be able to generate. For example, if company A sells product X through its sales force, company B sells product Y, and company A decides to buy company B, then the new company could use each salesperson to sell products X and Y, thereby increasing the revenue that each salesperson generates for the company.

In media revenue, synergy is the promotion and sale of a product throughout the various subsidiaries of a media conglomerate, e.g. films, soundtracks, or video games.

Financial

Financial synergy gained by the combined firm is a result of number of benefits which flow to the entity as a consequence of acquisition and merger. These benefits may be:

Cash slack

This is when a firm having a number of cash extensive projects acquires a firm which is cash-rich, thus enabling the new combined firm to enjoy the profits from investing the cash of one firm in the projects of the other.

Debt capacity

If two firms have no or little capacity to carry debt before individually, it is possible for them to join and gain the capacity to carry the debt through decreased gearing (leverage). This creates value for the firm, as debt is thought to be a cheaper source of finance.

Tax benefits

It is possible for one firm to have unused tax benefits which might be offset against the profits of another after combination, thus resulting in less tax being paid. However this greatly depends on the tax law of the country.

Management

Synergy in management and in relation to teamwork refers to the combined effort of individuals as participants of the team. The condition that exists when the organization's parts interact to produce a joint effect that is greater than the sum of the parts acting alone. Positive or negative synergies can exist. In these cases, positive synergy has positive effects such as improved efficiency in operations, greater exploitation of opportunities, and improved utilization of resources. Negative synergy on the other hand has negative effects such as: reduced efficiency of operations, decrease in quality, underutilization of resources and disequilibrium with the external environment.

Cost

A cost synergy refers to the opportunity of a combined corporate entity to reduce or eliminate expenses associated with running a business. Cost synergies are realized by eliminating positions that are viewed as duplicate within the merged entity. Examples include the headquarters office of one of the predecessor companies, certain executives, the human resources department, or other employees of the predecessor companies. This is related to the economic concept of economies of scale.

Synergistic action in economy

The synergistic action of the economic players lies within the economic phenomenon's profundity. The synergistic action gives different dimensions to competitiveness, strategy and network identity becoming an unconventional "weapon" which belongs to those who exploit the economic systems' potential in depth.

Synergistic determinants

The synergistic gravity equation (SYNGEq), according to its complex "title", represents a synthesis of the endogenous and exogenous factors which determine the private and non-private economic decision makers to call to actions of synergistic exploitation of the economic network in which they operate. That is to say, SYNGEq constitutes a big picture of the factors/motivations which determine the entrepreneurs to contour an active synergistic network. SYNGEq includes both factors which character is changing over time (such as the competitive conditions), as well as classics factors, such as the imperative of the access to resources of the collaboration and the quick answers. The synergistic gravity equation (SINGEq) comes to be represented by the formula:

where:

- ΣSYN.Act = the sum of the synergistic actions adopted (by the economic actor)

- Σ R- = the amount of unpurchased but necessary resources

- ICRed = the imperative for cost reductions

- ICOOP+ = the imperative for deep cooperation (functional interdependence)

- IAUnimit. = the imperative for purchasing unimitable competitive advantages (for the economic actor)

- VCust = the necessity of customer value in purchasing future profits and competitive advantages VInfo = the necessity of informational value in purchasing future profits and competitive advantages

- cc = the specific competitive conditions in which the economic actor operates

Synergistic networks and systems

The synergistic network represents an integrated part of the economic system which, through the coordination and control functions (of the undertaken economic actions), agrees synergies. The networks which promote synergistic actions can be divided in horizontal synergistic networks and vertical synergistic networks.

Synergy effects

The synergy effects are difficult (even impossible) to imitate by competitors and difficult to reproduce by their authors because these effects depend on the combination of factors with time-varying characteristics. The synergy effects are often called "synergistic benefits", representing the direct and implied result of the developed/adopted synergistic actions.

Computers

Synergy can also be defined as the combination of human strengths and computer strengths, such as advanced chess. Computers can process data much more quickly than humans, but lack the ability to respond meaningfully to arbitrary stimuli.

Synergy in literature

Etymologically, the "synergy" term was first used around 1600, deriving from the Greek word "synergos", which means "to work together" or "to cooperate". If during this period the synergy concept was mainly used in the theological field (describing "the cooperation of human effort with divine will"), in the 19th and 20th centuries, "synergy" was promoted in physics and biochemistry, being implemented in the study of the open economic systems only in the 1960 and 1970s.

In 1938, J. R. R. Tolkien wrote an essay titled On Fairy Stores, delivered at an Andrew Lang Lecture, and reprinted in his book, The Tolkien Reader, published in 1966. In it, he made two references to synergy, although he did not use that term. He wrote:

Faerie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible. It has many ingredients, but analysis will not necessarily discover the secret of the whole.

And more succinctly, in a footnote, about the "part of producing the web of an intricate story", he wrote:

It is indeed easier to unravel a single thread — an incident, a name, a motive — than to trace the history of any picture defined by many threads. For with the picture in the tapestry a new element has come in: the picture is greater than, and not explained by, the sum of the component threads.

The book "Synergy"

Synergy, a book: DION, Eric (2017), Synergy; A Theoretical Model of Canada's Comprehensive Approach, iUniverse, 308 pp.

Synergy in the media

The informational synergies which can be applied also in media involve a compression of transmission, access and use of information's time, the flows, circuits and means of handling information being based on a complementary, integrated, transparent and coordinated use of knowledge.

In media economics, synergy is the promotion and sale of a product (and all its versions) throughout the various subsidiaries of a media conglomerate, e.g. films, soundtracks or video games. Walt Disney pioneered synergistic marketing techniques in the 1930s by granting dozens of firms the right to use his Mickey Mouse character in products and ads, and continued to market Disney media through licensing arrangements. These products can help advertise the film itself and thus help to increase the film's sales. For example, the Spider-Man films had toys of webshooters and figures of the characters made, as well as posters and games. The NBC sitcom 30 Rock often shows the power of synergy, while also poking fun at the use of the term in the corporate world. There are also different forms of synergy in popular card games like Magic: The Gathering, Yu-Gi-Oh!, Cardfight!! Vanguard, and Future Card Buddyfight.